Case Presentation

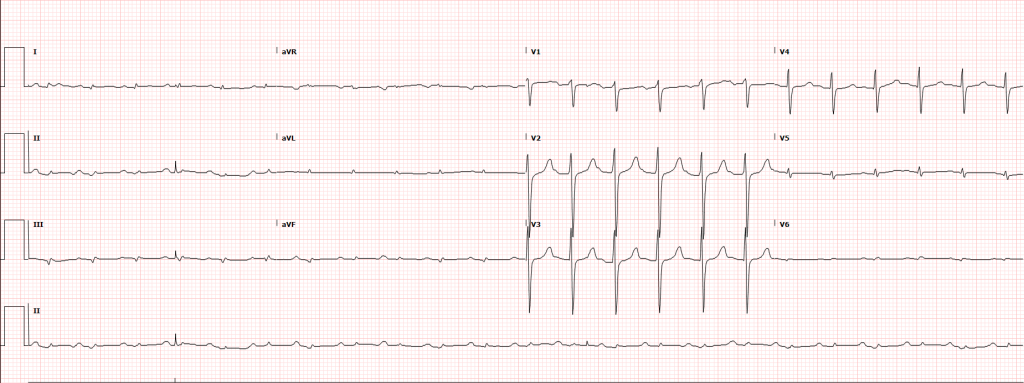

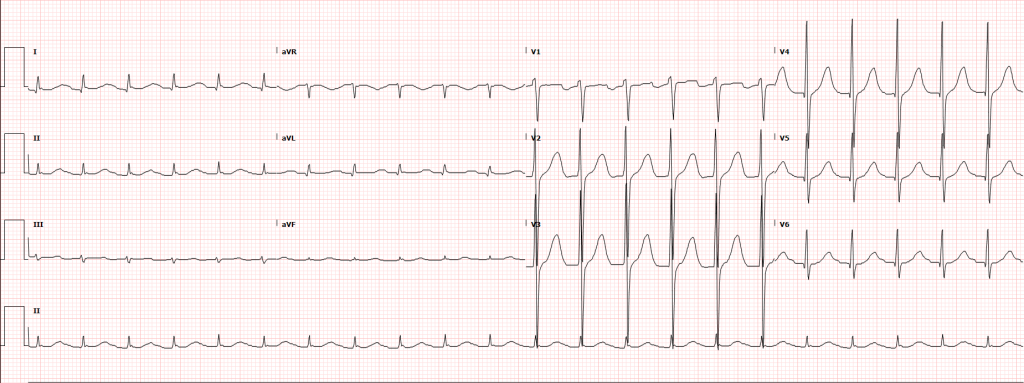

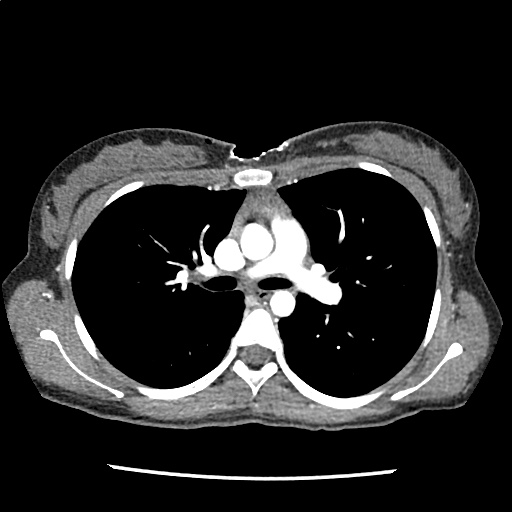

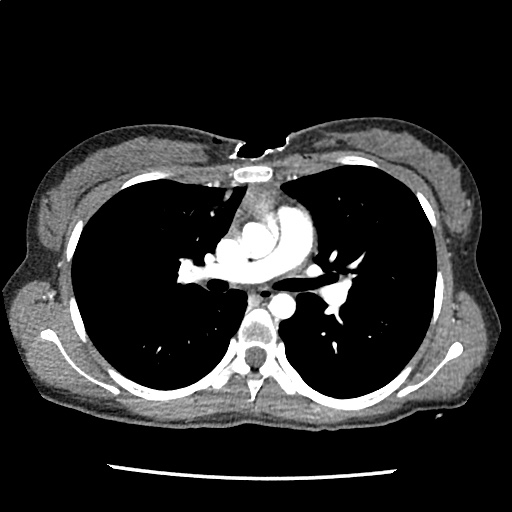

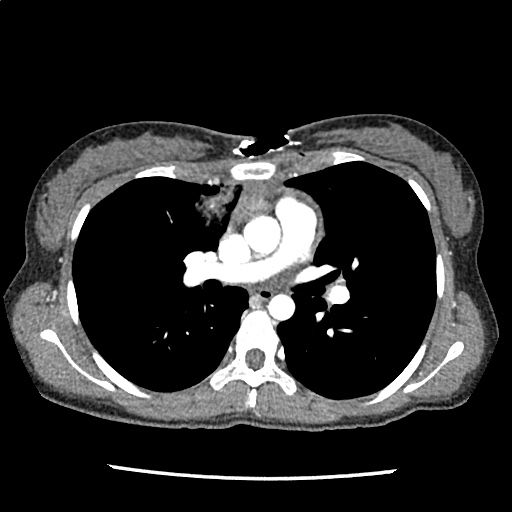

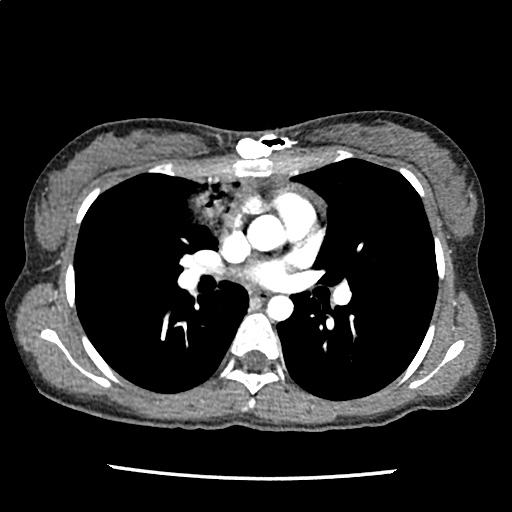

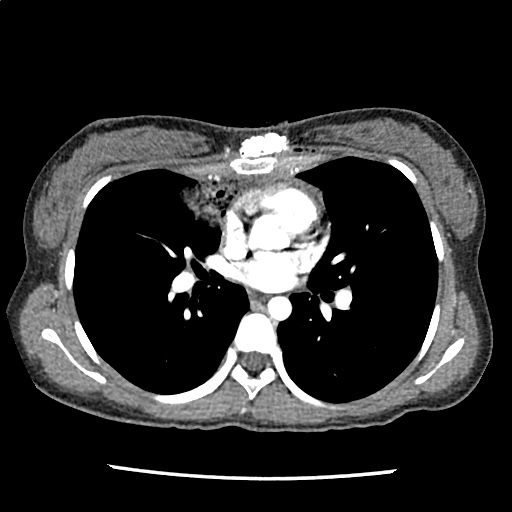

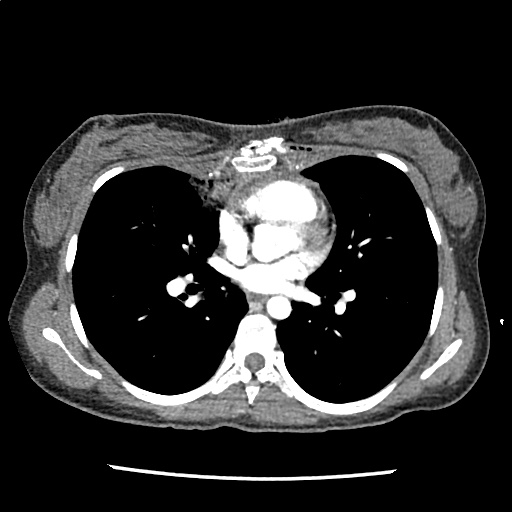

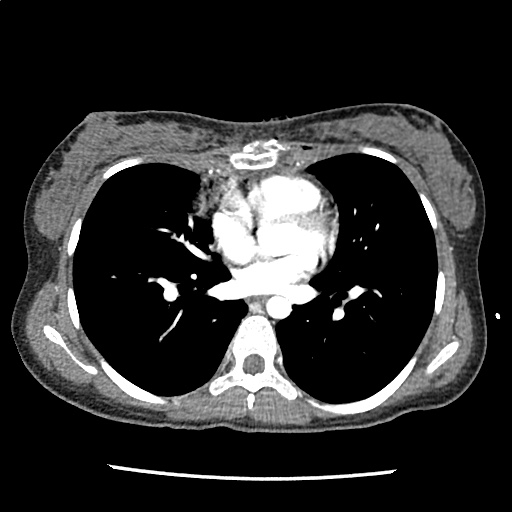

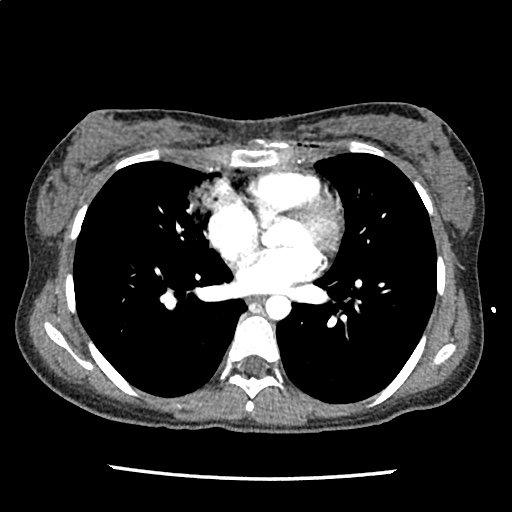

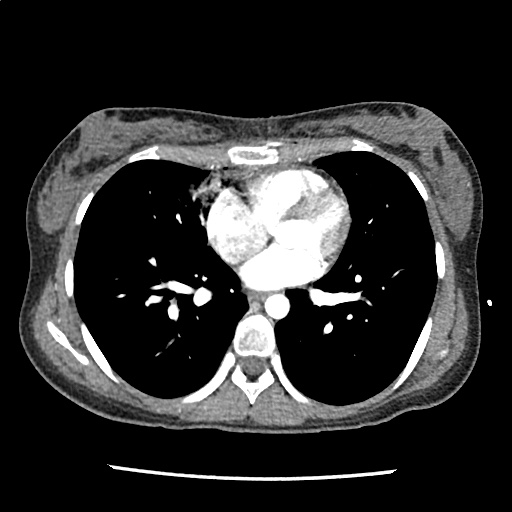

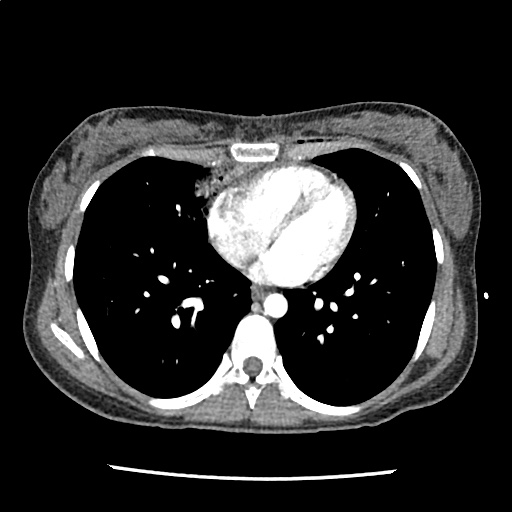

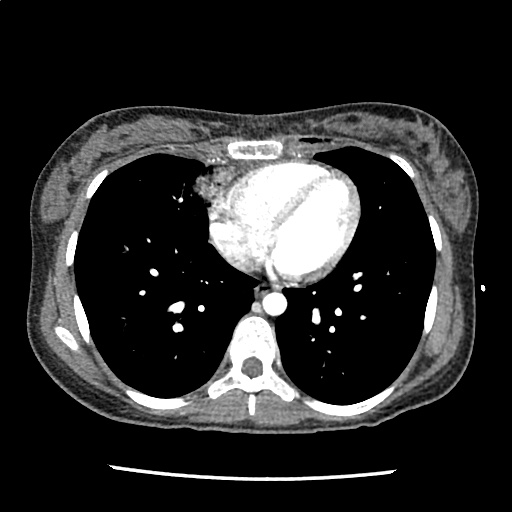

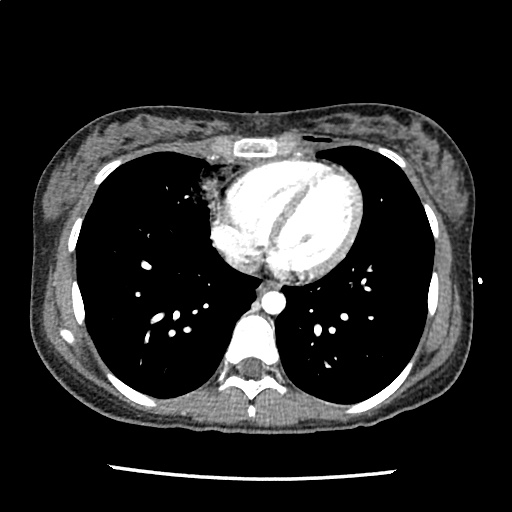

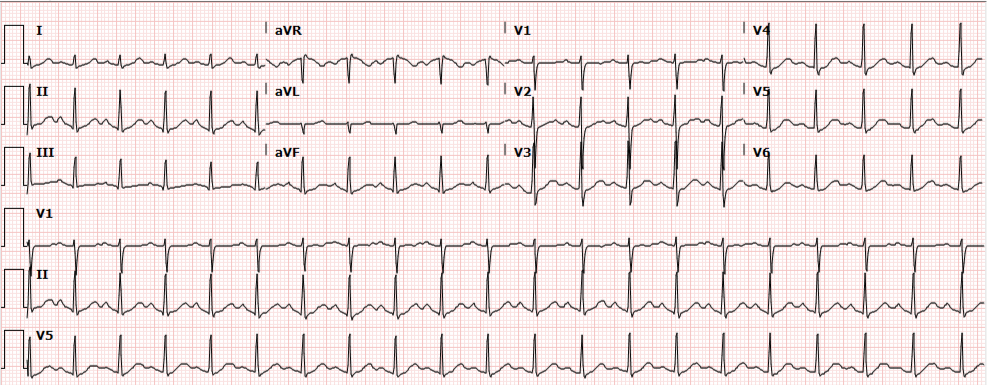

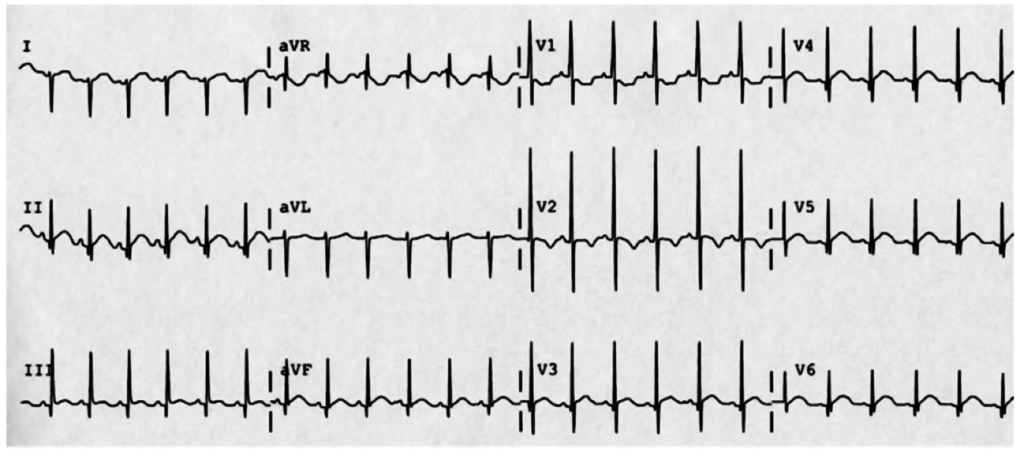

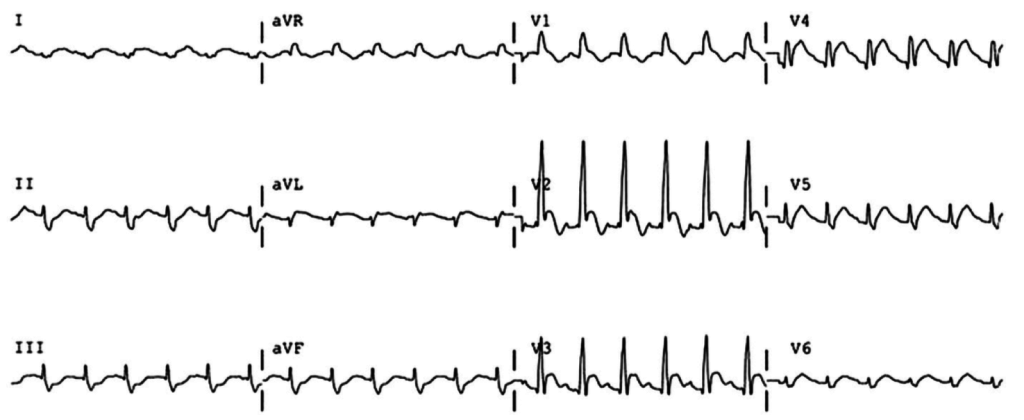

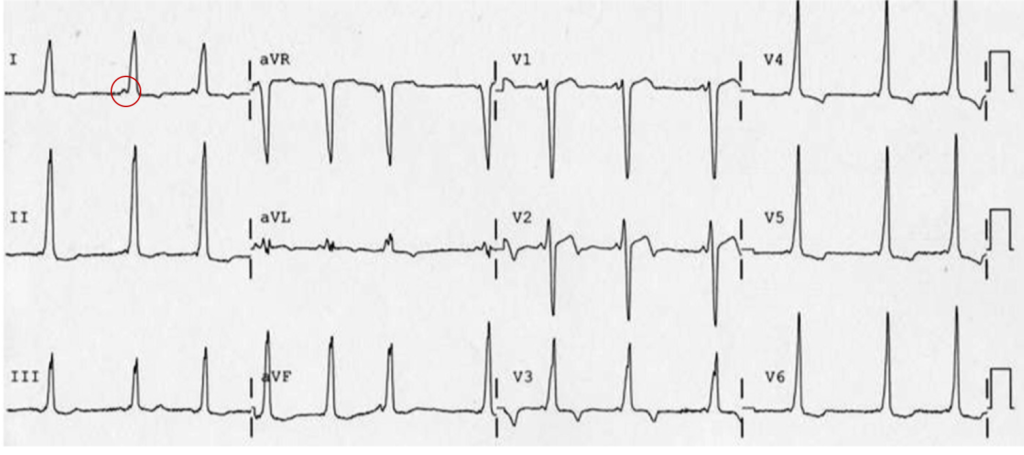

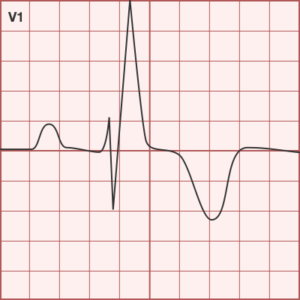

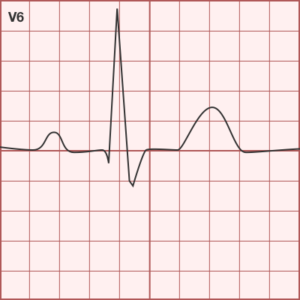

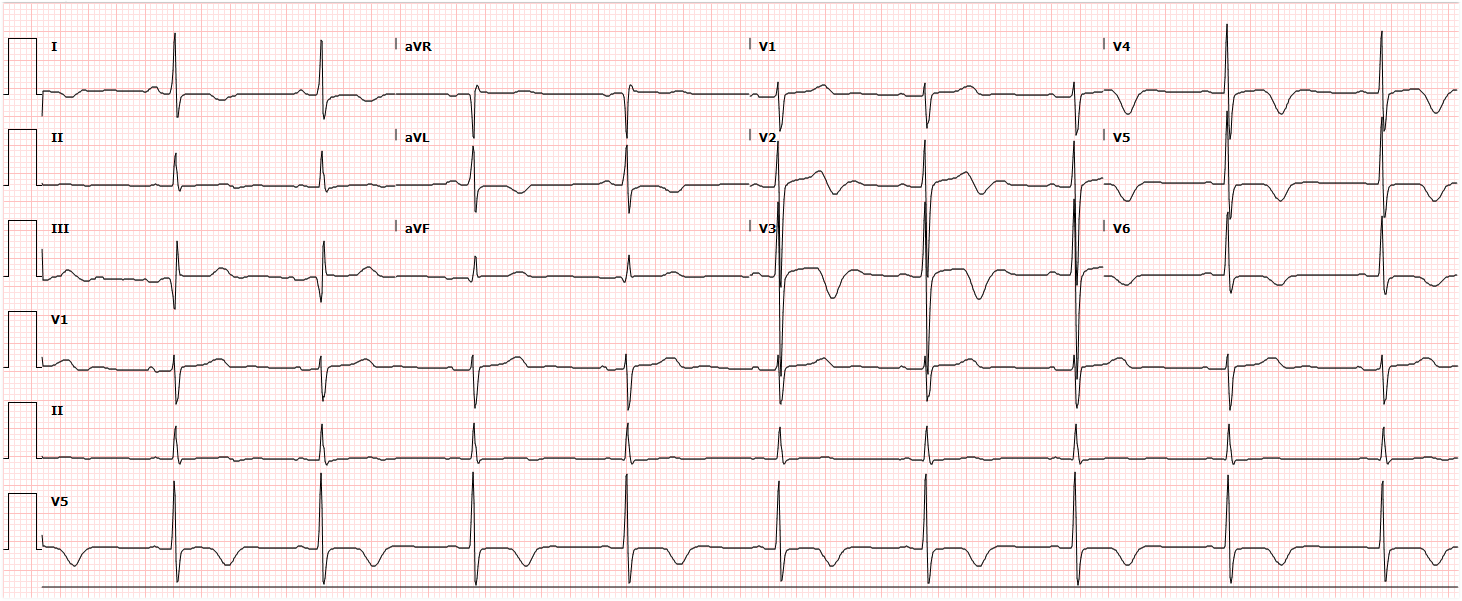

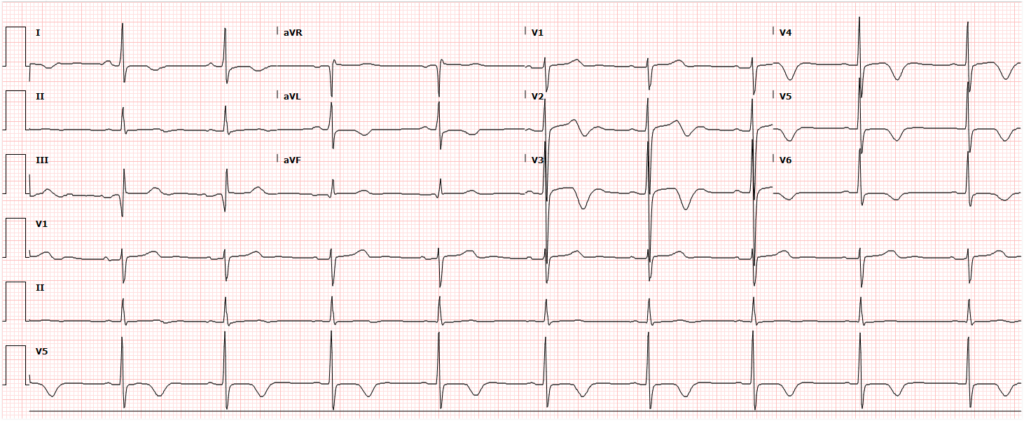

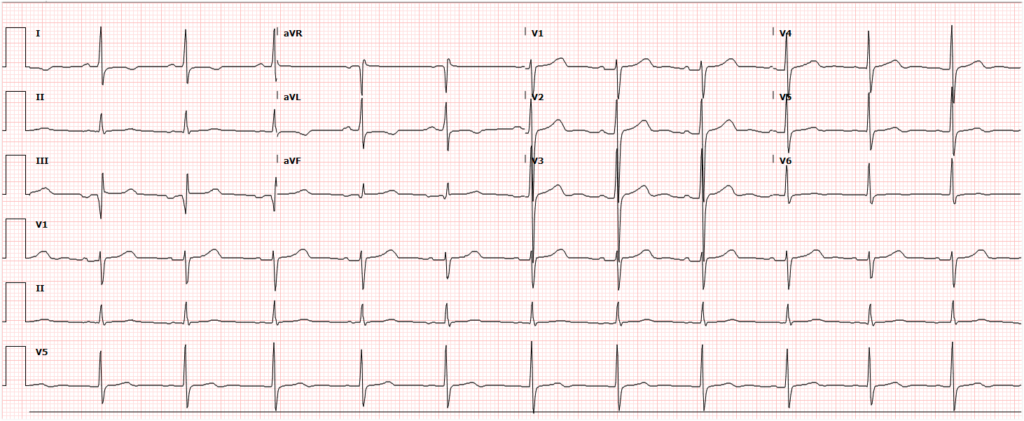

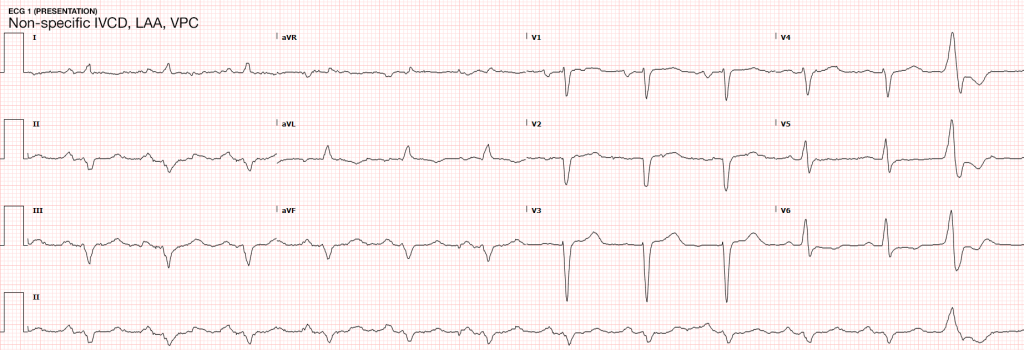

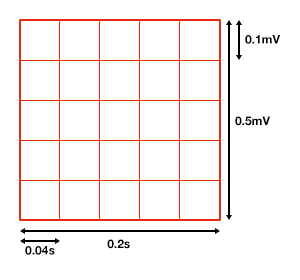

A 35-year-old female with no past medical history is brought in by ambulance to the emergency department. She was struck by a firework (“Roman Candle”) which lodged in her mid-chest until the propellant was consumed. She transiently lost consciousness but was awake upon EMS arrival. She complains of pleuritic chest pain. Examination reveals a circular 4x4cm full-thickness burn to the mid-chest with surrounding deep and superficial partial-thickness burns. Her ECG shows normal sinus rhythm, the initial serum troponin I is 32.9 (normal <0.012). CT angiography of the thorax is obtained.

Mechanisms

Blunt cardiac injury (BCI) may be induced by multiple forces including direct thoracic trauma, crush injury of mediastinal contents between the sternum and thoracic spine, rapid deceleration causing tears at venous-atrial confluences, abrupt pressure changes from rapid compression of abdominal contents, blast injury, or laceration from bone fracture fragments1. The most common mechanisms of injury are motor vehicle collisions (50%), auto versus pedestrian (35%), motorcycle accidents (9%) and falls from significant height (>6m)2.

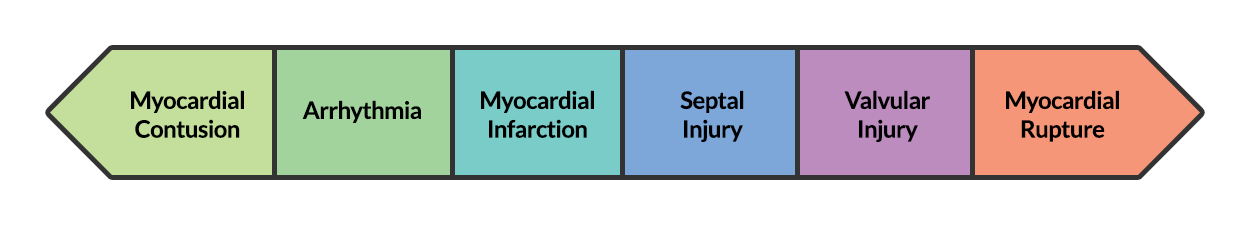

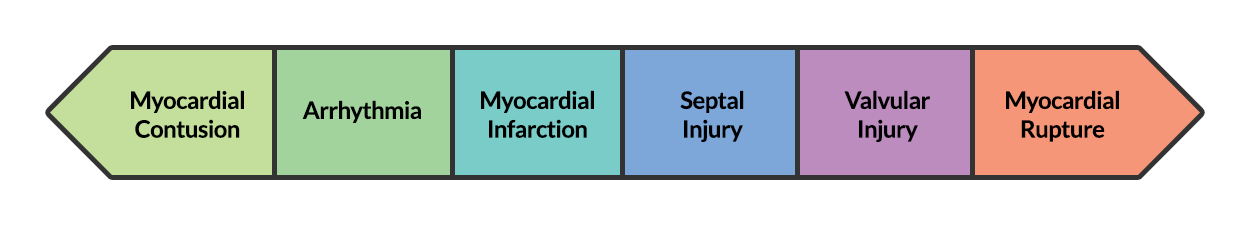

BCI represents a spectrum of conditions. Diagnosis is both challenging and critical as clinical manifestations can be absent or rapidly fatal.

At one end of the spectrum is myocardial contusion. The lack of a gold-standard for the diagnosis of this clinical entity has led to a preference for describing associated abnormalities if present3,4, including cardiac dysfunction (identified on echocardiography) or the next entity along the spectrum – arrhythmia.

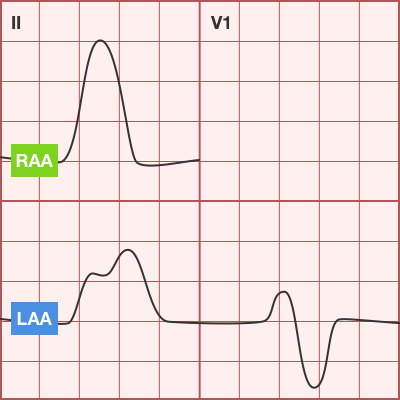

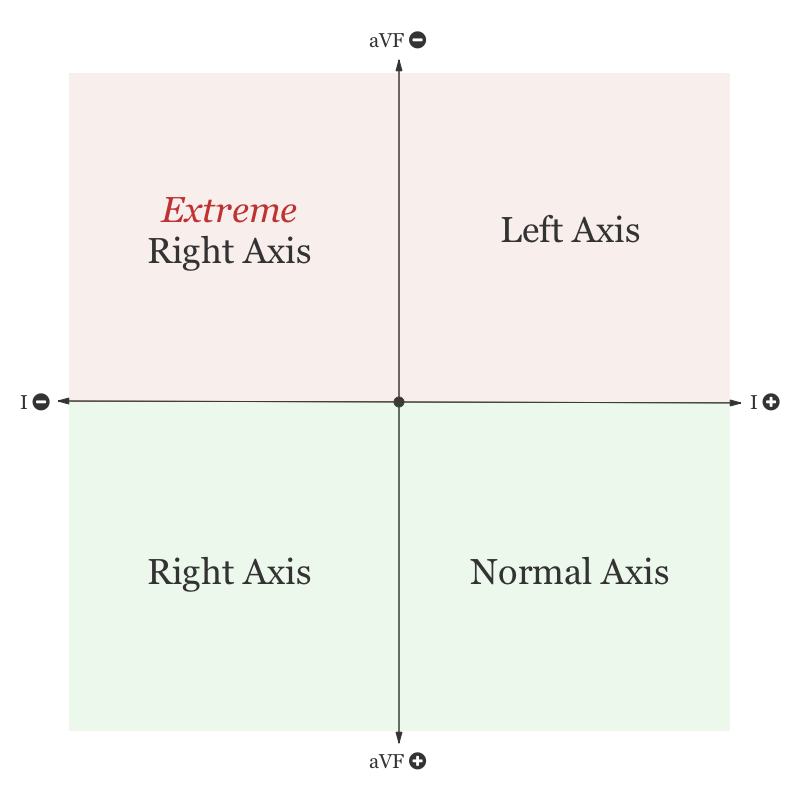

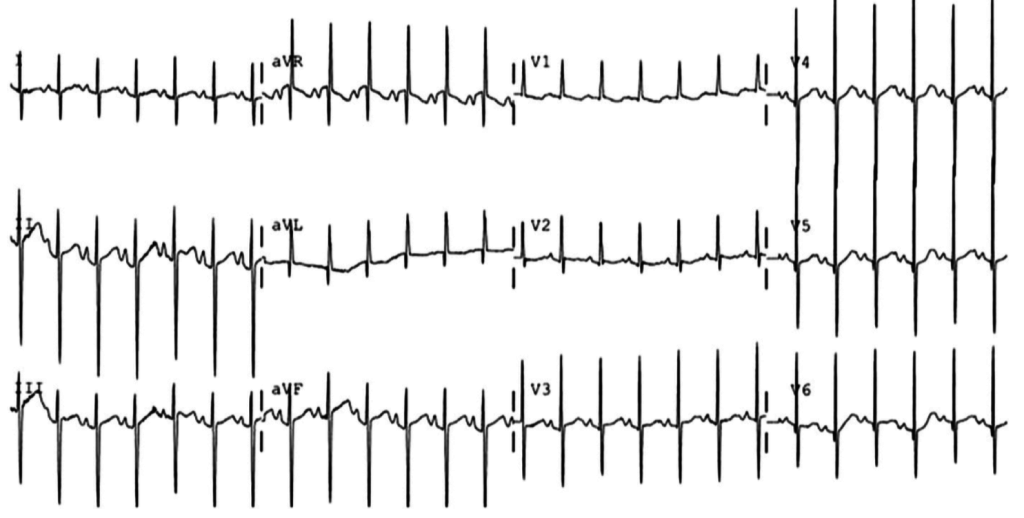

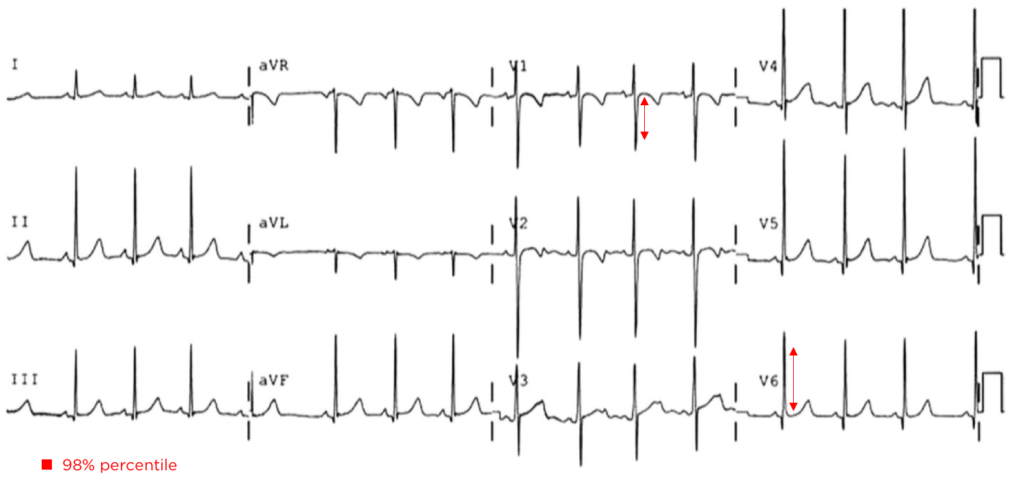

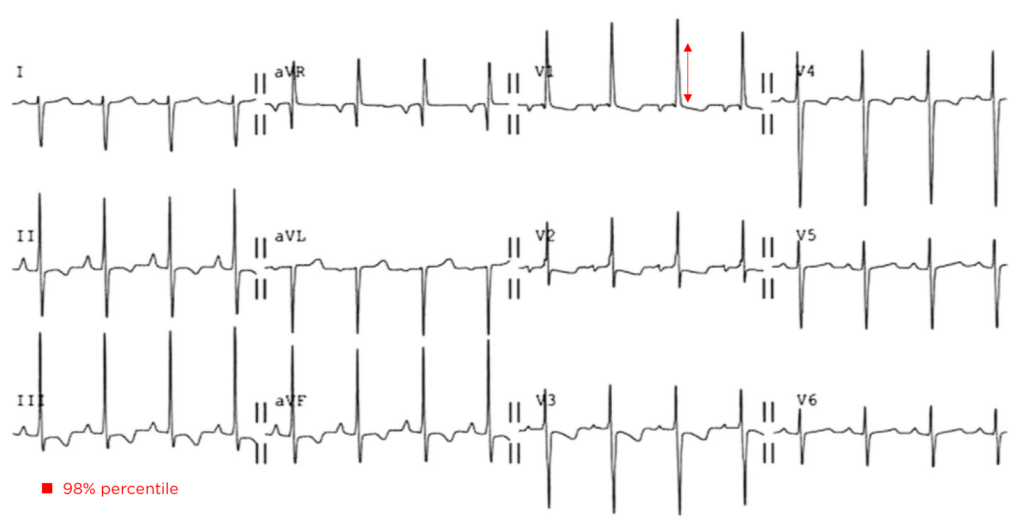

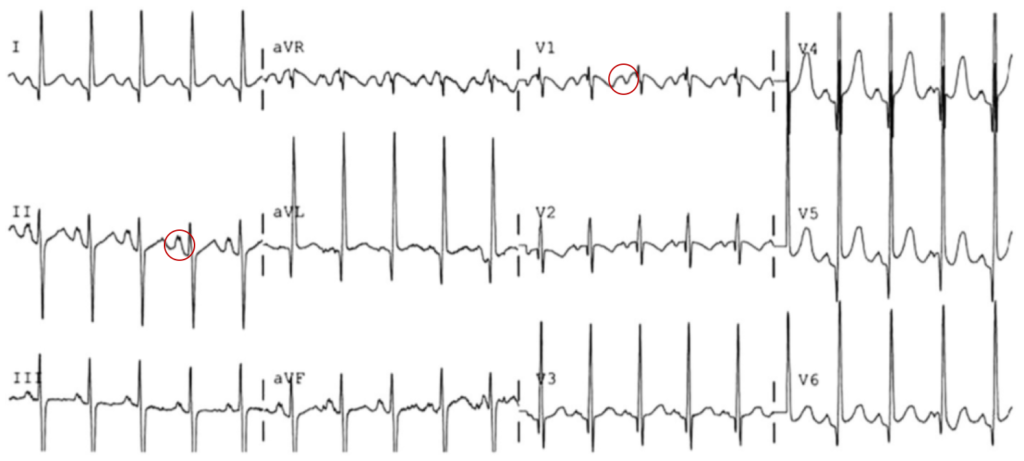

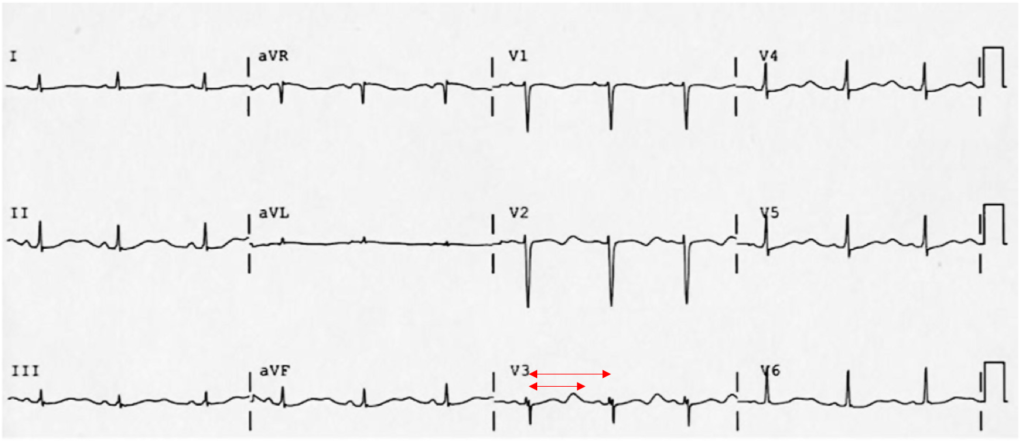

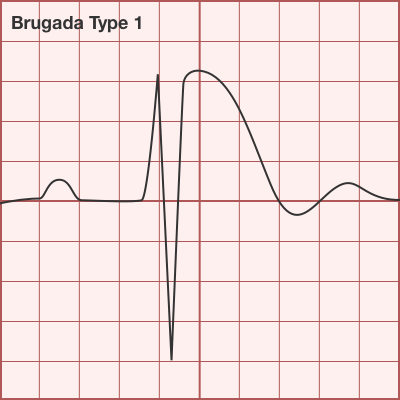

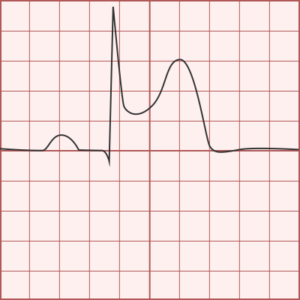

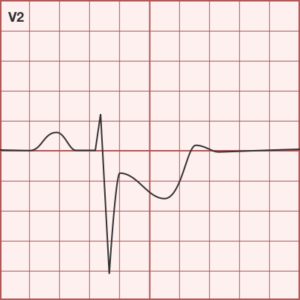

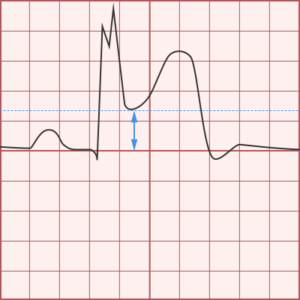

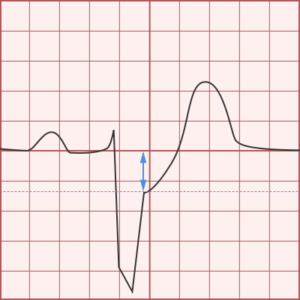

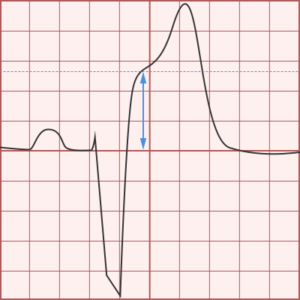

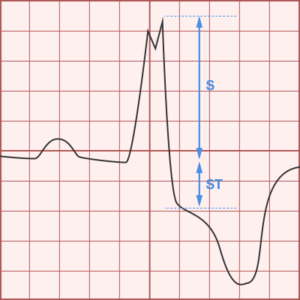

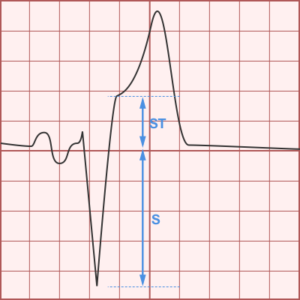

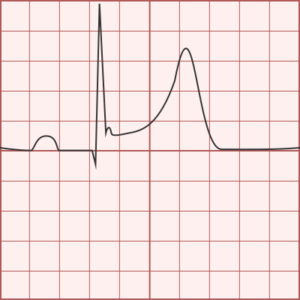

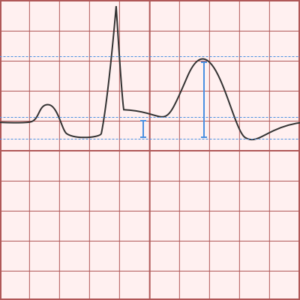

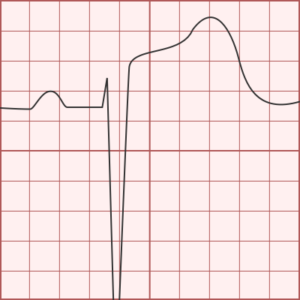

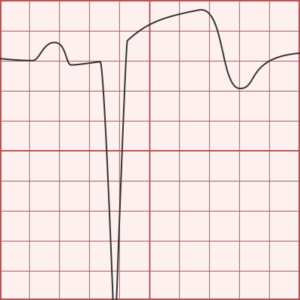

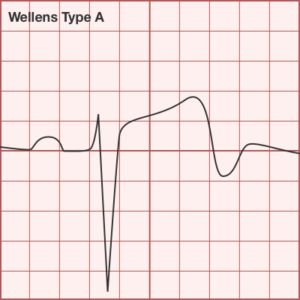

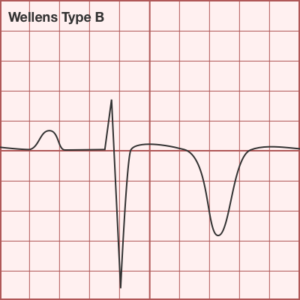

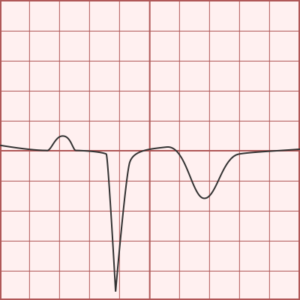

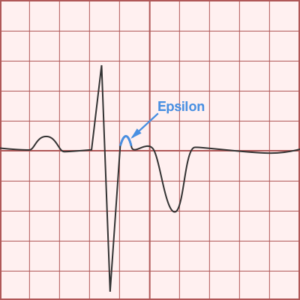

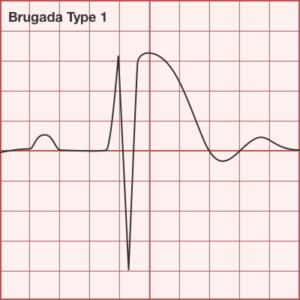

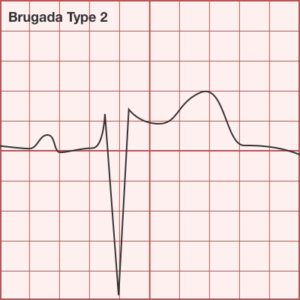

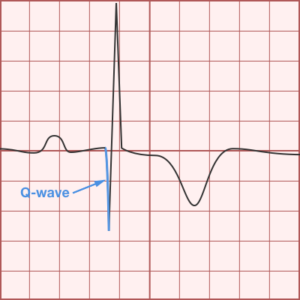

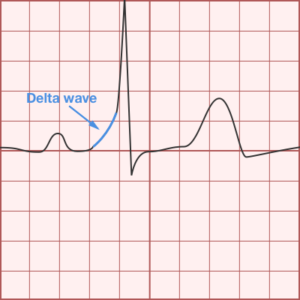

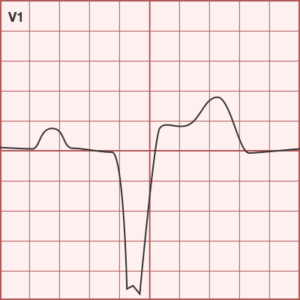

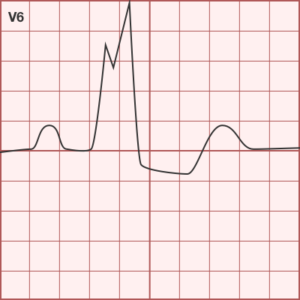

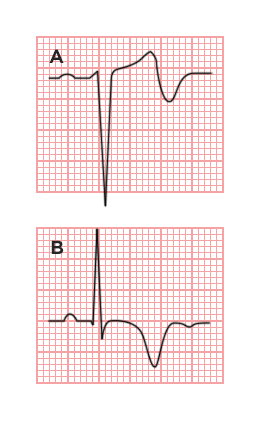

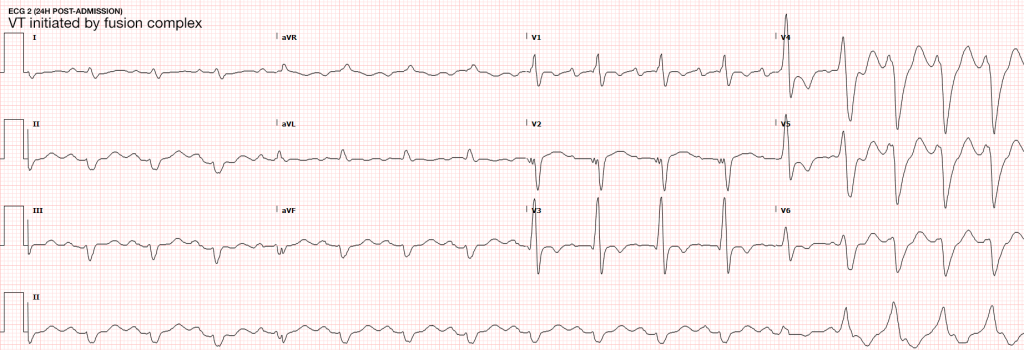

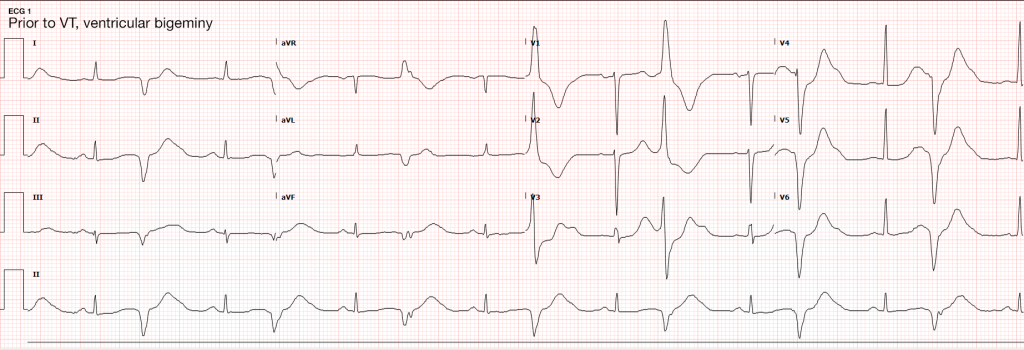

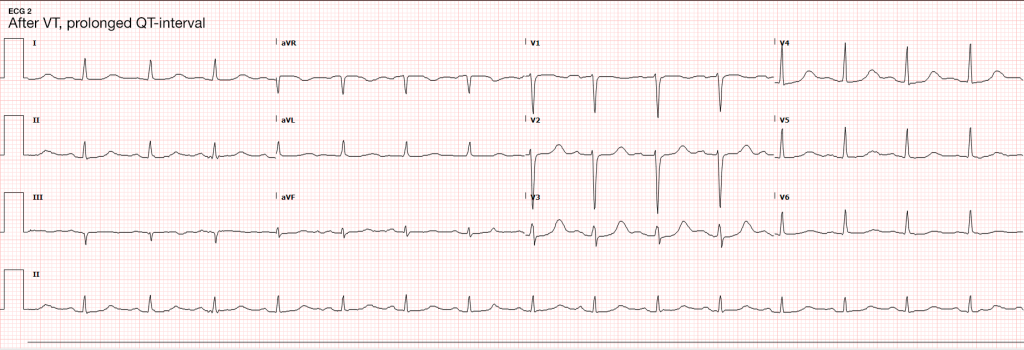

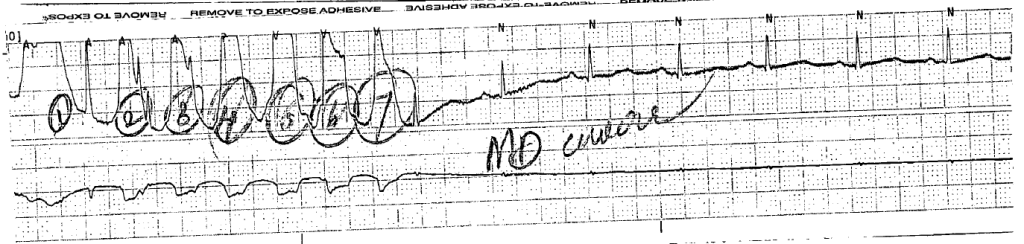

The most common arrhythmia identified in blunt cardiac injury is sinus tachycardia, followed by premature atrial or ventricular contractions, T-wave changes, and atrial fibrillation or flutter5. Commotio cordis is a unique arrhythmia induced by untimely precordial impact (often in sports) during a vulnerable phase of ventricular excitability, resulting in ventricular fibrillation2.

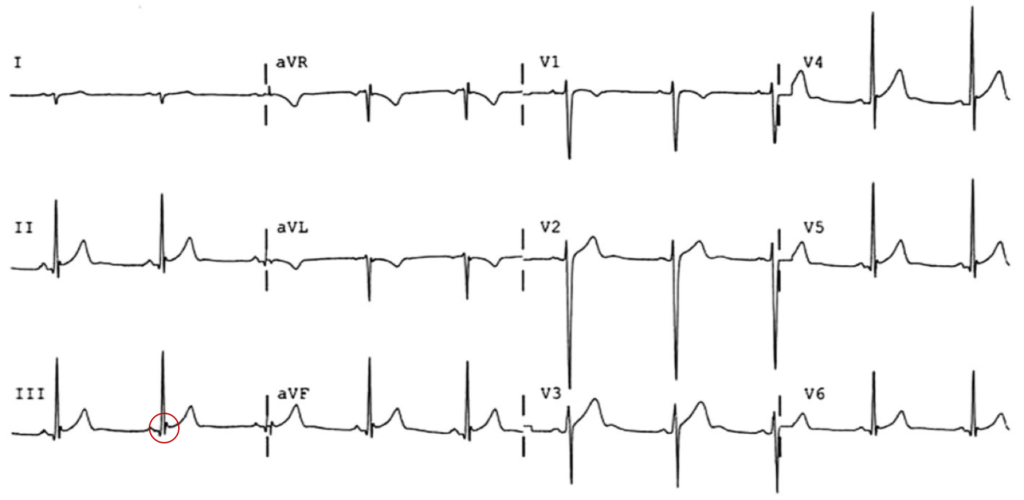

ST-segment elevations after blunt cardiac injury should raise concern for myocardial infarction due to coronary artery dissection, laceration or thrombosis (often in already-diseased vessels) 5,6.

The remaining disease entities are increasingly rare, require careful examination or imaging for diagnosis, and are more likely to be non-survivable. Septal injury can range from small tears to rupture. Valvular injury most commonly affects the aortic valve (followed by mitral and tricuspid valves) and involves damage to leaflets, or rupture of papillary muscles or chordae tendineae. The clinical presentation is of acute valvular insufficiency, including acute heart failure and murmur2,7,8. A widened pulse pressure may be noted with aortic valve injury, and the manifestations of valvular injury may be delayed9. Finally, myocardial wall rupture is unlikely to be survivable, though patients may present with cardiac tamponade if rupture is small or contained2.

Evaluation

The primary diagnostic modalities for the assessment of BCI in the emergency department include assessment for pericardial fluid during the Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (FAST), electrocardiography and cardiac enzymes.

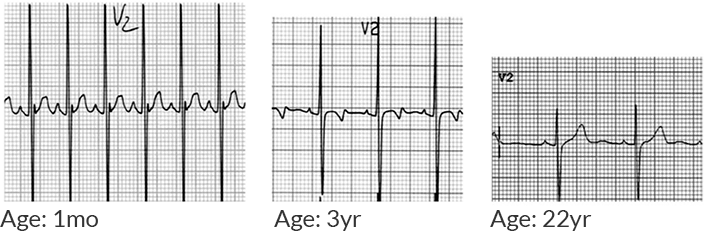

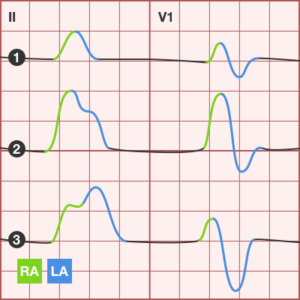

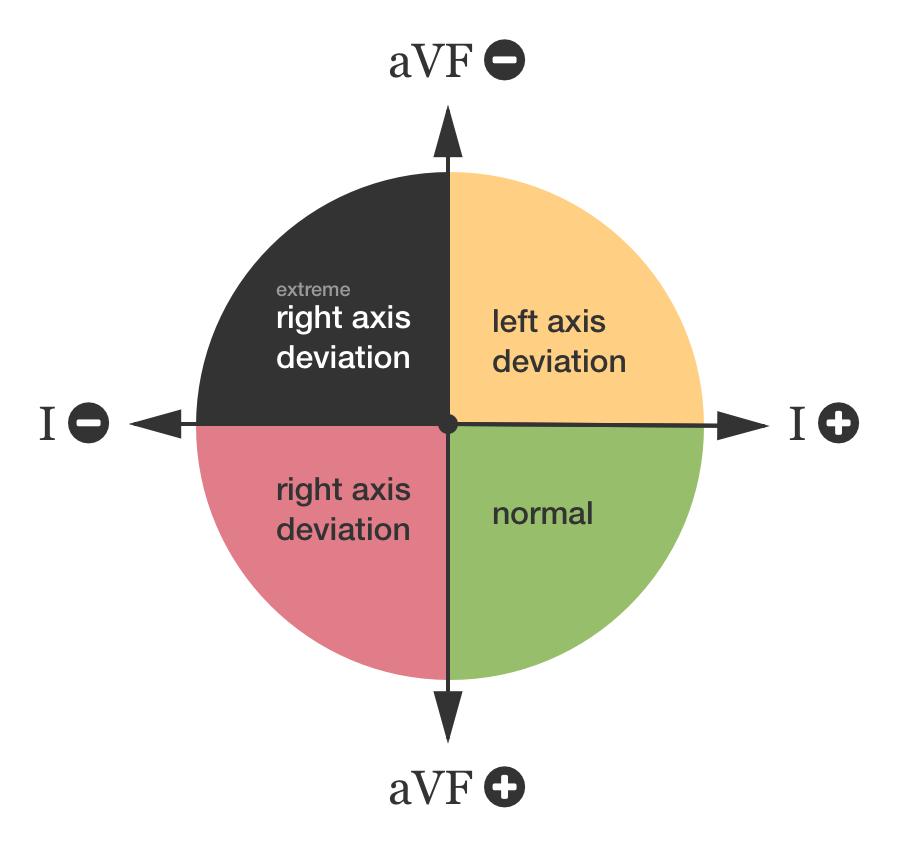

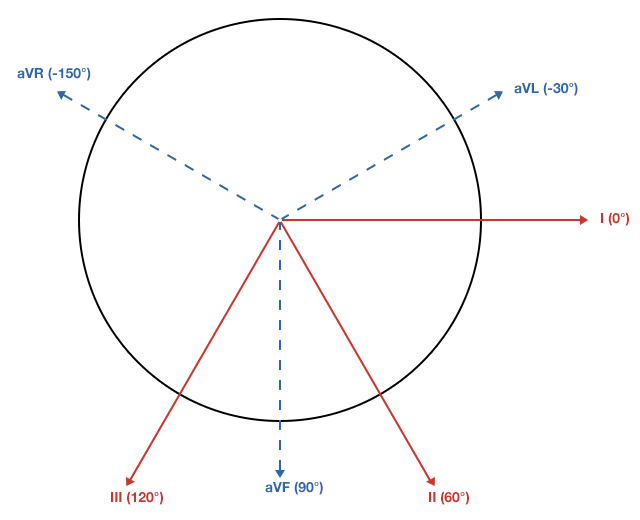

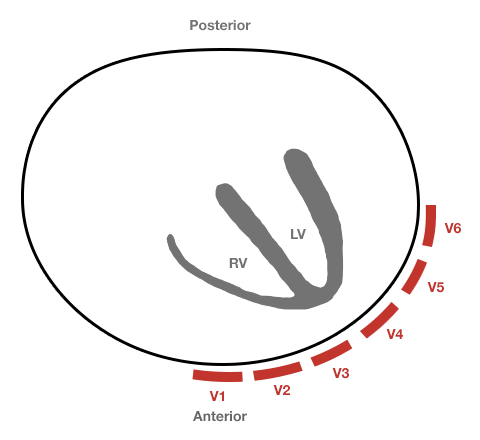

While specific for identifying patients at risk of complications of BCI, electrocardiography alone is not sufficient to exclude BCI. In one study, only 59% of patient with echocardiographic evidence of BCI (wall-motion abnormalities, other chamber abnormalities) had initially abnormal ECG’s10. In another study, 41% of patients with initially normal ECG’s developed clinically significant abnormalities11. The use of specialized electrocardiography including right-sided ECG (proposed to better detect right-ventricular abnormalities which are more commonly associated with BCI) and signal-averaged ECG is not supported11,12.

Several studies have supported the use of serum troponin for the detection of clinically significant BCI – particularly in combination with electrocardiography. A prospective study in 2001 evaluating patients with blunt thoracic trauma using ECG at admission and 8-hours, as well as troponin I at admission, 4- and 8-hours had a negative predictive value of 100% for significant BCI (arrhythmia requiring treatment, shock, or structural cardiac abnormalities) in patients with initially normal ECG and troponin13.

Another prospective study adding to the population evaluated by Salim et al. included 41 patients with normal ECG’s and troponin levels at admission and 8-hours who were admitted for significant mechanisms, none developed significant BCI (again described as arrhythmia requiring treatment, shock, or structural cardiac abnormalities) after 1 to 3 days of observation14. The precise timing of serum troponin analysis remains unclear.

While FAST may detect hemopericardium warranting immediate intervention, formal echocardiography is indicated for patients with unexplained hypotension (to evaluate for valvular injury or regional wall-motion abnormalities) or persistent arrhythmias (to evaluate for arrhythmogenic intramural hematomas)15. The presence of sternal fractures was previously thought to increase risk of BCI and mandate echocardiography, however this notion is no longer supported16-18. The role of advanced imaging including helical CT (cardiac-gated), and MRI remains unclear19.

Algorithm for the Evaluation of Blunt Thoracic Trauma

Notes:

† Arrest in ED, immediate chest tube output >20ml/kg (>1.5L) or >200mL/hr for 2-4hr.

Management

Management of BCI depends on the pathologic process localized along the spectrum defined above. Persistent hypotension after appropriate evaluation for alternative etiologies may represent myocardial contusion with cardiac dysfunction and should be evaluated with echocardiography. Similarly, echocardiography and observation with continuous telemetry monitoring is indicated for any new arrhythmia or persistent and unexplained tachycardia. Patients with only elevation of the serum troponin without electrocardiographic abnormalities or obvious cardiac dysfunction should also be admitted for observation and serial cardiac enzymes. Traumatic myocardial infarction, valvular injury, or post-traumatic structural myocardial defects should be managed in consultation with cardiothoracic surgery5,19-21.

Case Conclusion

The CT interpretation noted the soft-tissue defect identified on examination as well as associated pulmonary contusions and a non-displaced sternal fracture. The patient went to the operating room for washout and debridement. A transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated trace mitral regurgitation and a small pericardial effusion. She remained hemodynamically stable and serial troponin measures downtrended – no dysrhythmias were noted on telemetry monitoring. She was discharged on hospital day four with a negative-pressure wound dressing.

References

- Schultz JM, Trunkey DD. Blunt cardiac injury. Crit Care Clin. 2004;20(1):57-70.

- Yousef R, Carr JA. Blunt cardiac trauma: a review of the current knowledge and management. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98(3):1134-1140. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.04.043.

- Mattox KL, Flint LM, Carrico CJ, et al. Blunt cardiac injury. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 1992;33(5):649-650.

- Sybrandy KC, Cramer MJM, Burgersdijk C. Diagnosing cardiac contusion: old wisdom and new insights. Heart. 2003;89(5):485-489.

- Elie M-C. Blunt cardiac injury. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73(2):542-552.

- Edouard AR, Felten M-L, Hebert J-L, Cosson C, Martin L, Benhamou D. Incidence and significance of cardiac troponin I release in severe trauma patients. Anesthesiology. 2004;101(6):1262-1268.

- Cordovil A, Fischer CH, Rodrigues ACT, et al. Papillary Muscle Rupture After Blunt Chest Trauma. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2006;19(4):469.e1-469.e3. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2005.12.005.

- Pasquier M, Sierro C, Yersin B, Delay D, Carron P-N. Traumatic Mitral Valve Injury After Blunt Chest Trauma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 2010;68(1):243-246. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3181bb881e.

- Ismailov RM, Weiss HB, Ness RB, Lawrence BA, Miller TR. Blunt cardiac injury associated with cardiac valve insufficiency: trauma links to chronic disease? Injury. 2005;36(9):1022-1028. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2005.05.028.

- García-Fernández MA, López-Pérez JM, Pérez-Castellano N, et al. Role of transesophageal echocardiography in the assessment of patients with blunt chest trauma: correlation of echocardiographic findings with the electrocardiogram and creatine kinase monoclonal antibody measurements. Am Heart J. 1998;135(3):476-481.

- Fulda GJ, Giberson F, Hailstone D, Law A, Stillabower M. An evaluation of serum troponin T and signal-averaged electrocardiography in predicting electrocardiographic abnormalities after blunt chest trauma. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 1997;43(2):304–10–discussion310–2.

- Walsh P, Marks G, Aranguri C, et al. Use of V4R in patients who sustain blunt chest trauma. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 2001;51(1):60-63.

- Salim A, Velmahos GC, Jindal A, et al. Clinically significant blunt cardiac trauma: role of serum troponin levels combined with electrocardiographic findings. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 2001;50(2):237-243.

- Velmahos GC, Karaiskakis M, Salim A, et al. Normal electrocardiography and serum troponin I levels preclude the presence of clinically significant blunt cardiac injury. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 2003;54(1):45–50–discussion50–1. doi:10.1097/01.TA.0000046315.73441.D8.

- Nagy KK, Krosner SM, Roberts RR, Joseph KT, Smith RF, Barrett J. Determining which patients require evaluation for blunt cardiac injury following blunt chest trauma. World J Surg. 2001;25(1):108-111.

- Roy-Shapira A, Levi I, Khoda J. Sternal fractures: a red flag or a red herring? The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 1994;37(1):59-61.

- Hills MW, Delprado AM, Deane SA. Sternal fractures: associated injuries and management. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 1993;35(1):55-60.

- Rashid MA, Ortenwall P, Wikström T. Cardiovascular injuries associated with sternal fractures. Eur J Surg. 2001;167(4):243-248. doi:10.1080/110241501300091345.

- Clancy K, Velopulos C, Bilaniuk JW, et al. Screening for blunt cardiac injury: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(5 Suppl 4):S301-S306. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e318270193a.

- El-Menyar A, Thani Al H, Zarour A, Latifi R. Understanding traumatic blunt cardiac injury. Ann Card Anaesth. 2012;15(4):287-295. doi:10.4103/0971-9784.101875.

- Hockberger RS, Walls RM. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine. Mosby Incorporated; 2002.