Brief HPI:

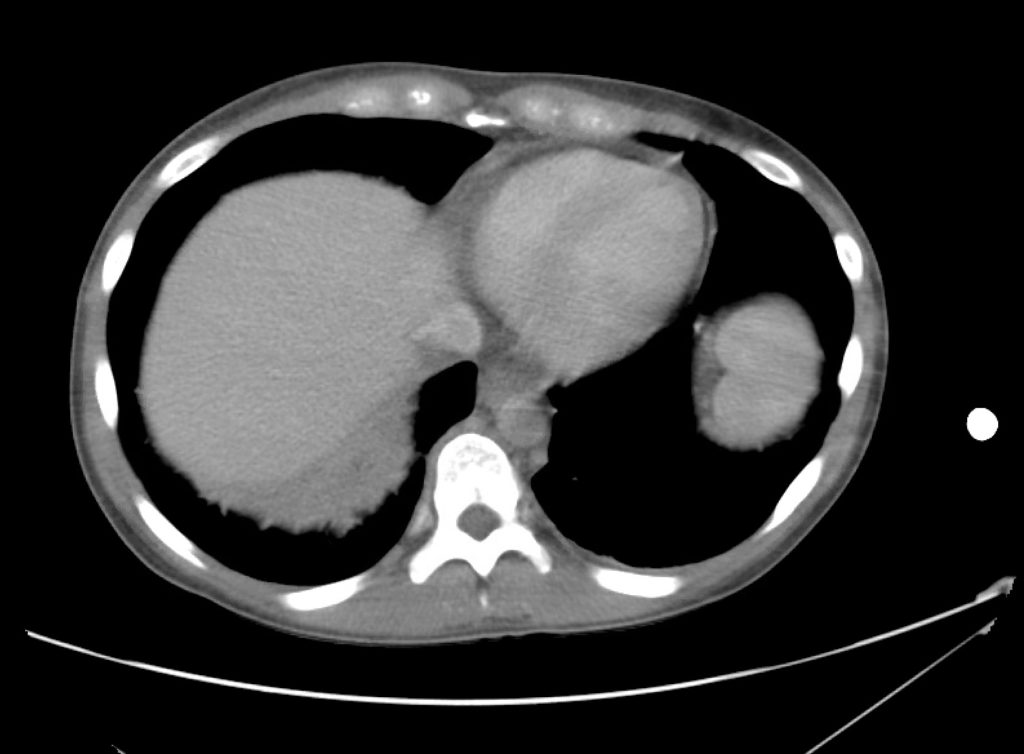

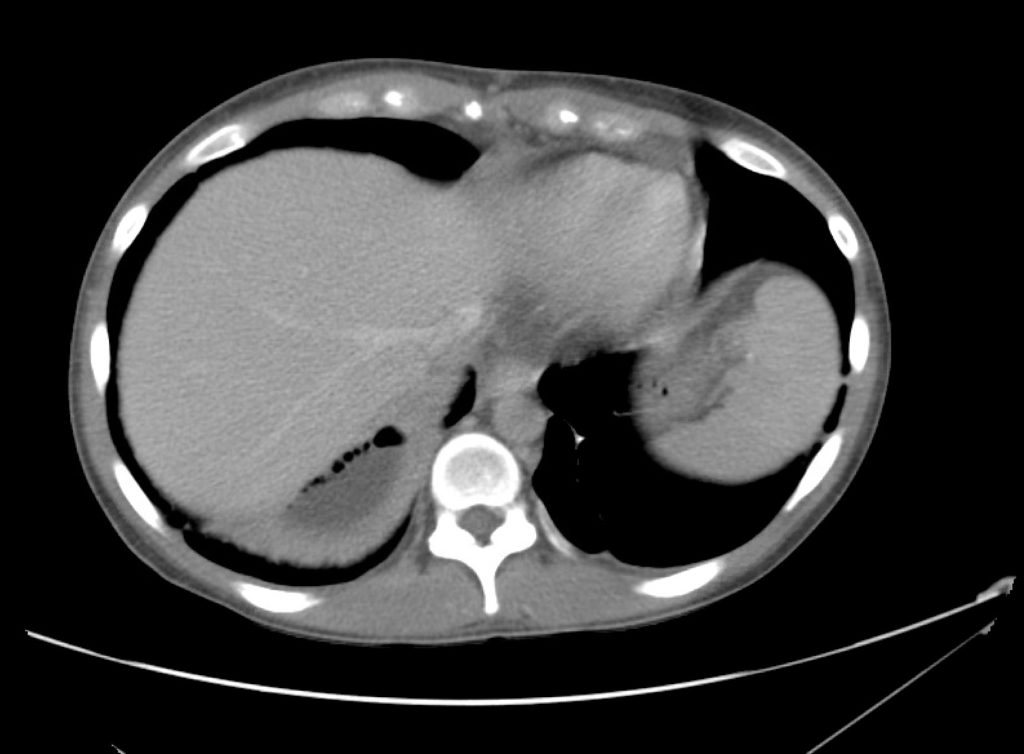

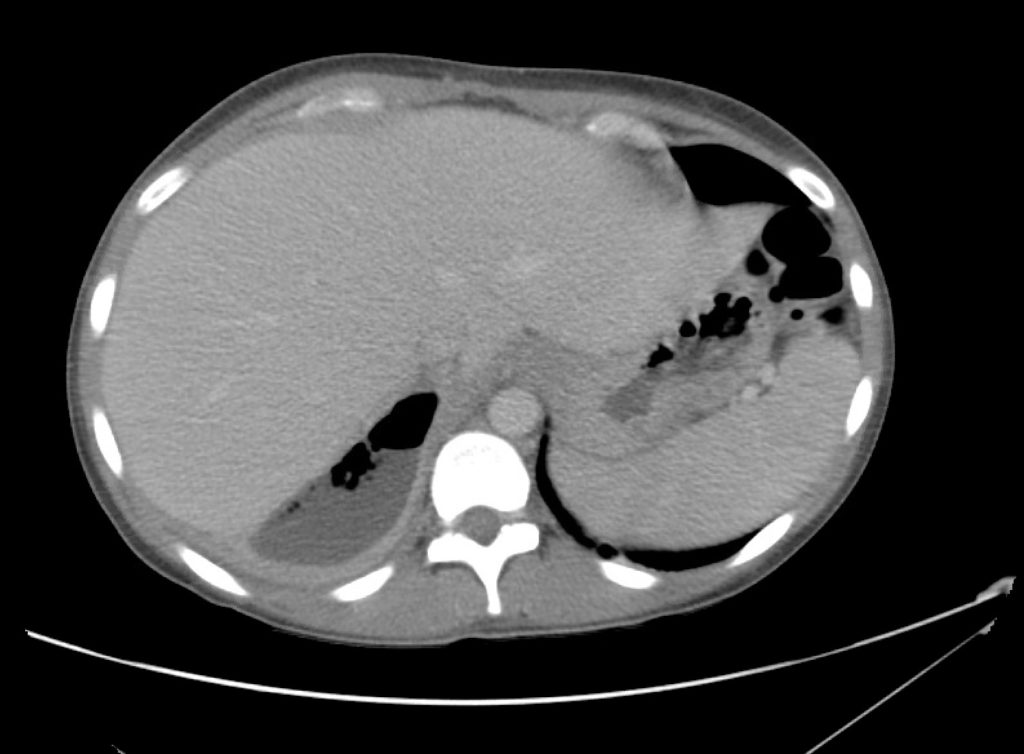

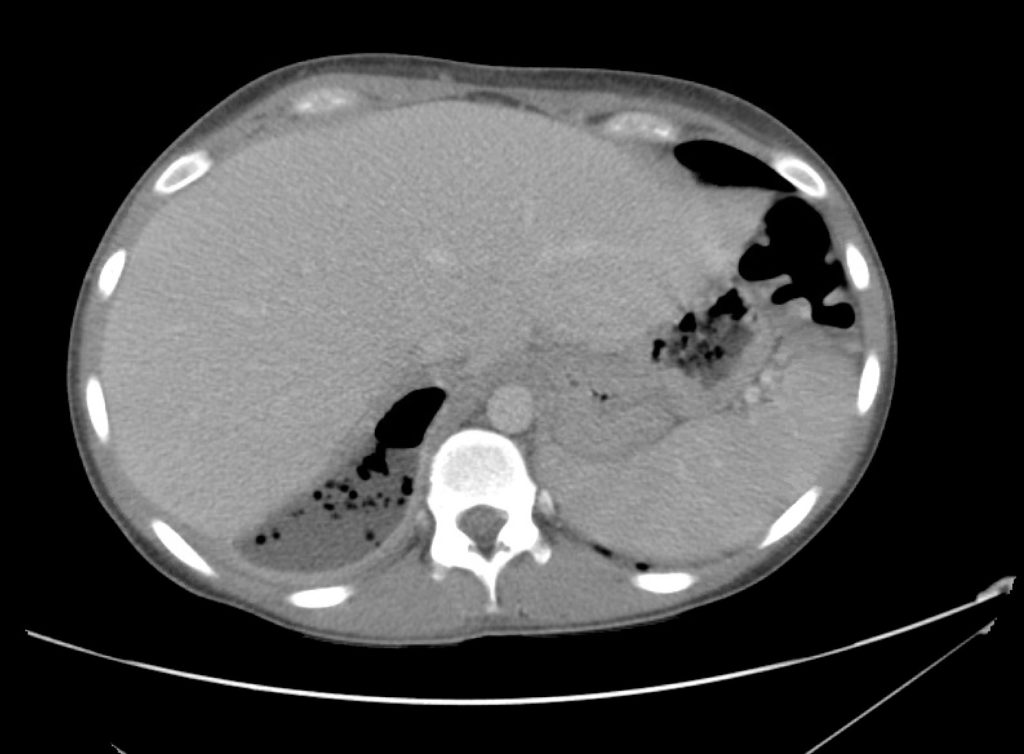

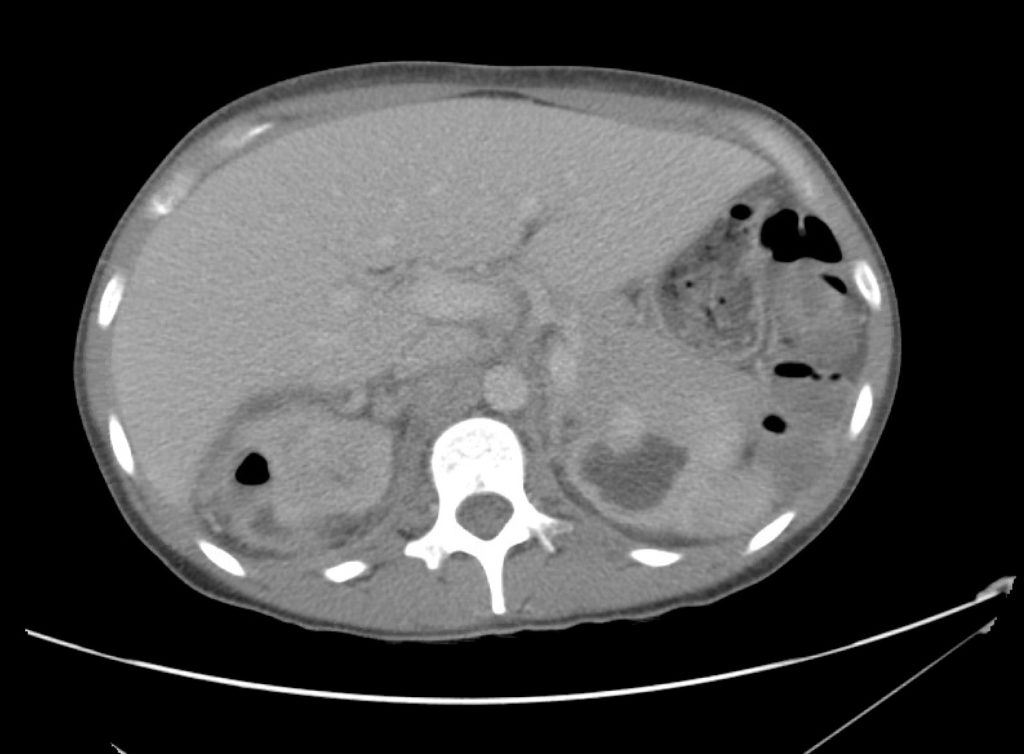

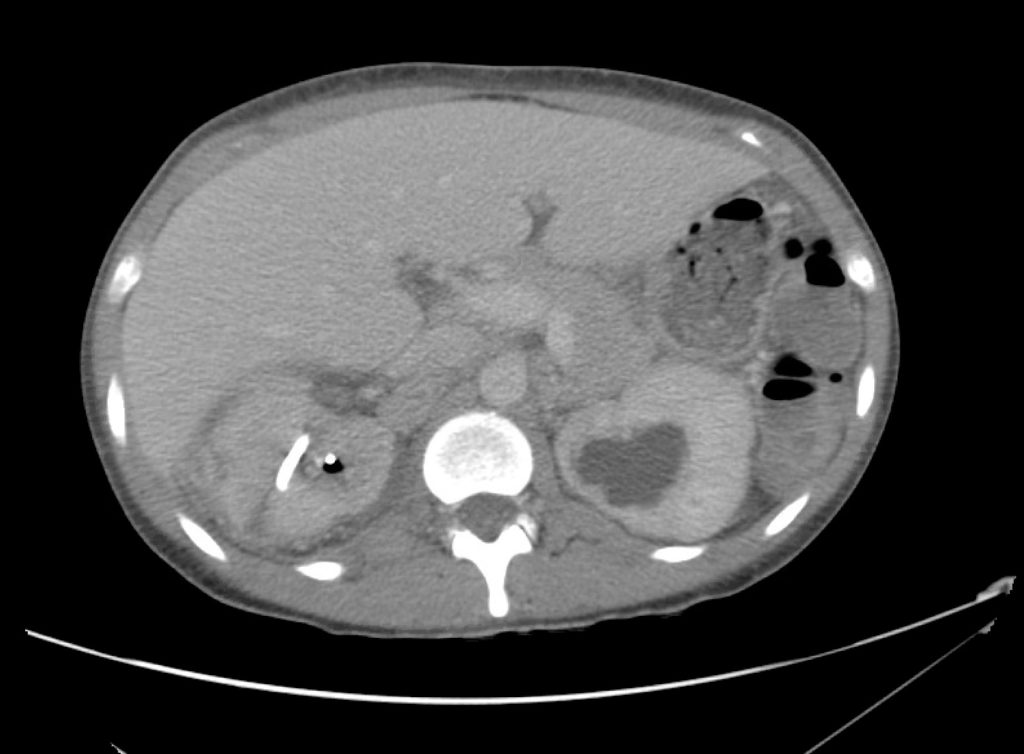

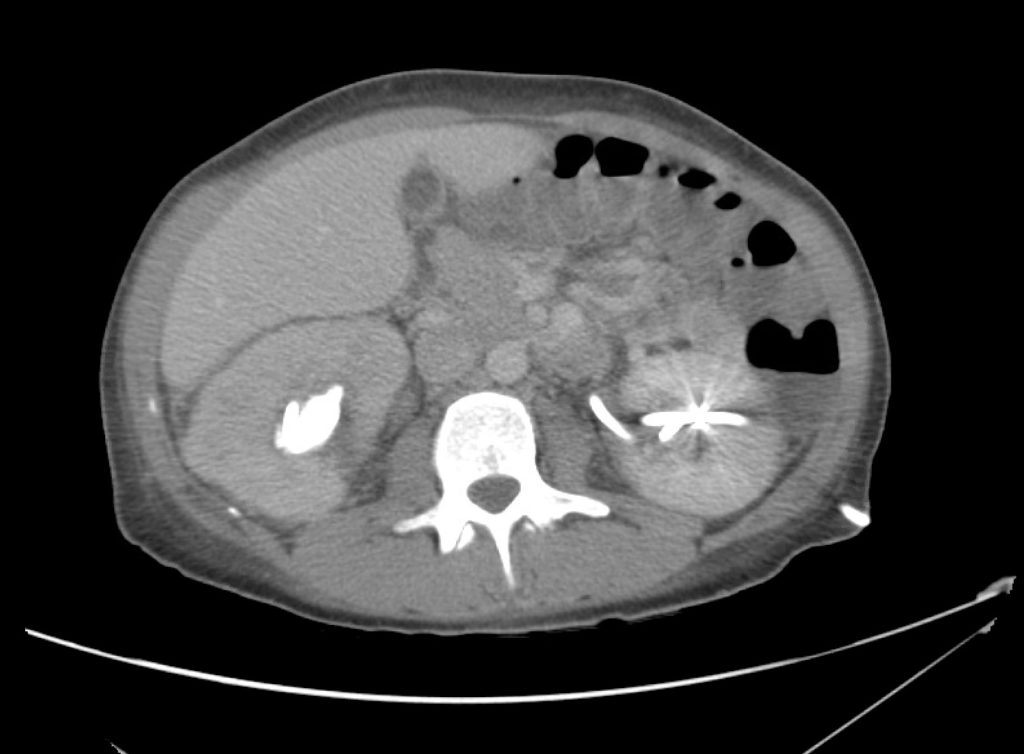

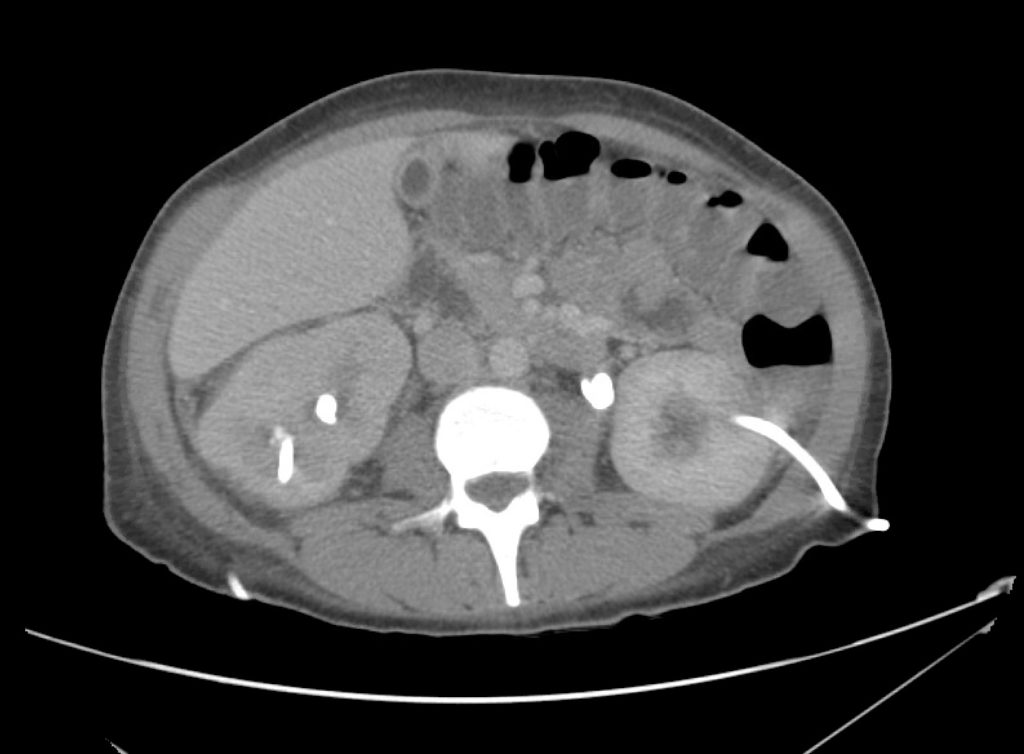

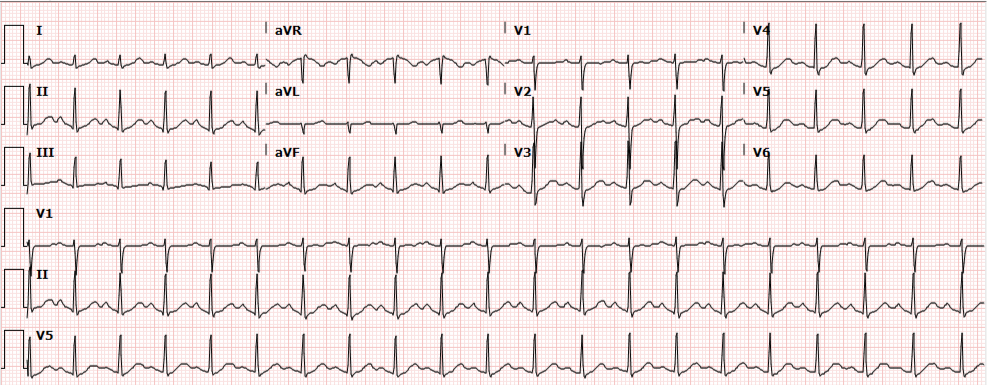

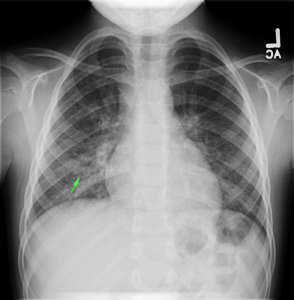

A 45 year-old female with a history of ureterolithiasis s/p bilateral percutaneous nephrostomies, hypertension and diabetes presents to the emergency department with flank pain and dysuria for two days. She noted that output from her right nephrostomy had diminished. On evaluation, her vital signs are notable for fever and tachycardia but are otherwise normal. Examination demonstrates right costovertebral angle tenderness to percussion. Drain sites appeared normal, without overlying erythema. Urinalyses from both nephrostomy collection bags were submitted. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained to evaluate for nephrostomy malposition.

CT Abdomen/Pelvis Interpretation

Complex perirenal fluid collection with gas suggestive of emphysematous pyelonephritis with abscess.

Hospital Course

The patient was treated with parenteral antibiotics based on prior culture data and was admitted to the intensive care unit with urology consultation and plan for interventional radiology percutaneous drainage. The patient underwent uncomplicated perinephric drain placement and nephrostomy exchange and was discharged on hospital day five to complete a course of oral antibiotics.

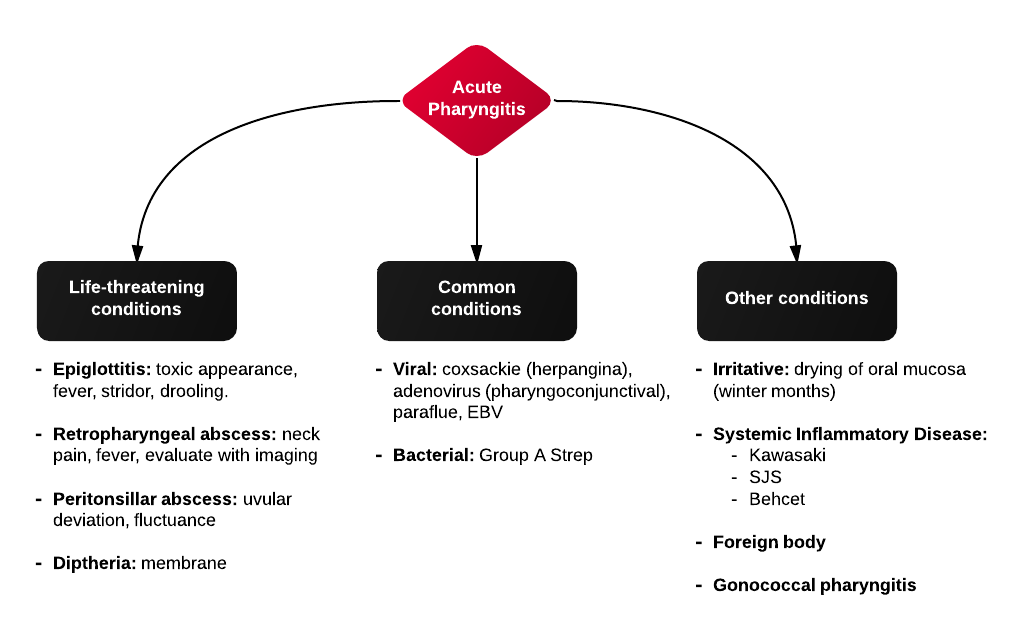

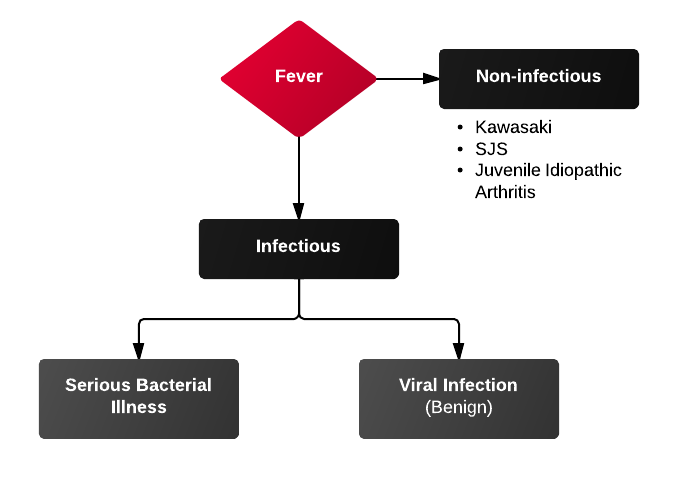

An Algorithm for the Evaluation and Management of Emphysematous Urinary Tract Infections

References

- Evanoff GV, Thompson CS, Foley R, Weinman EJ. Spectrum of gas within the kidney. Emphysematous pyelonephritis and emphysematous pyelitis. Am J Med. 1987;83(1):149-154.

- Wan YL, Lee TY, Bullard MJ, Tsai CC. Acute gas-producing bacterial renal infection: correlation between imaging findings and clinical outcome. Radiology. 1996;198(2):433-438. doi:10.1148/radiology.198.2.8596845.

- Shokeir AA, El-Azab M, Mohsen T, El-Diasty T. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: a 15-year experience with 20 cases. Urology. 1997;49(3):343-346. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(96)00501-8.

- Chen MT, Huang CN, Chou YH, Huang CH, Chiang CP, Liu GC. Percutaneous drainage in the treatment of emphysematous pyelonephritis: 10-year experience. JURO. 1997;157(5):1569-1573.

- Huang JJ, Tseng CC. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: clinicoradiological classification, management, prognosis, and pathogenesis. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(6):797-805.

- Roy C, Pfleger DD, Tuchmann CM, Lang HH, Saussine CC, Jacqmin D. Emphysematous pyelitis: findings in five patients. Radiology. 2001;218(3):647-650. doi:10.1148/radiology.218.3.r01fe14647.

- Park BS, Lee S-J, Kim YW, Huh JS, Kim JI, Chang S-G. Outcome of nephrectomy and kidney-preserving procedures for the treatment of emphysematous pyelonephritis. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2006;40(4):332-338. doi:10.1080/00365590600794902.

- Grupper M, Kravtsov A, Potasman I. Emphysematous cystitis: illustrative case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86(1):47-53. doi:10.1097/MD.0b013e3180307c3a.

- Mokabberi R, Ravakhah K. Emphysematous urinary tract infections: diagnosis, treatment and survival (case review series). Am J Med Sci. 2007;333(2):111-116.

- Yao J, Gutierrez OM, Reiser J. Emphysematous pyelonephritis. Kidney Int. 2007;71(5):462-465. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5002001.

- Thomas AA, Lane BR, Thomas AZ, Remer EM, Campbell SC, Shoskes DA. Emphysematous cystitis: a review of 135 cases. BJU Int. 2007;100(1):17-20. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06930.x.

- Falagas ME, Alexiou VG, Giannopoulou KP, Siempos II. Risk factors for mortality in patients with emphysematous pyelonephritis: a meta-analysis. JURO. 2007;178(3 Pt 1):880–5–quiz1129. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.017.

- Somani BK, Nabi G, Thorpe P, et al. Is percutaneous drainage the new gold standard in the management of emphysematous pyelonephritis? Evidence from a systematic review. J Urol. 2008;179(5):1844-1849. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.019.

- Aswathaman K, Gopalakrishnan G, Gnanaraj L, Chacko NK, Kekre NS, Devasia A. Emphysematous pyelonephritis: outcome of conservative management. Urology. 2008;71(6):1007-1009. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2007.12.095.

- Kapoor R, Muruganandham K, Gulia AK, et al. Predictive factors for mortality and need for nephrectomy in patients with emphysematous pyelonephritis. BJU Int. 2010;105(7):986-989. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08930.x.

- Ubee SS, McGlynn L, Fordham M. Emphysematous pyelonephritis. BJU Int. 2011;107(9):1474-1478. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09660.x.

- Lu Y-C, Chiang B-J, Pong Y-H, et al. Predictors of failure of conservative treatment among patients with emphysematous pyelonephritis. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14(1):418. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-14-418.