Case Presentation

HPI:

34M with no PMH presenting with joint pain and rash. The patient was in his usual state of good health until 1 week prior to presentation, noting bilateral shoulder pain. Diagnosed with musculoskeletal process at outside hospital and discharged with analgesics. Presented with partner due to worsening pain involving multiple joints, a non-painful, non-pruritic rash on bilateral lower extremities, and apparent confusion/hallucinations. Social history was non-contributory, no recent procedures or instrumentation.

Objectively, vital signs were notable for tachycardia and elevated core temperature. The patient was ill-appearing, disoriented and unable to provide detailed history. Skin examination was notable for non-blanching petechial rash with areas of confluence most dense in anterior distal lower extremities, rarer proximally, and otherwise without palm/sole involvement. Mucous membranes were dry, neck was supple. There was tenderness to palpation and manipulation of bilateral shoulders. No back tenderness to palpation or percussion was identified. Neurological examination notable for disorientation, intact cranial nerve function, pain-limited weakness in bilateral upper extremities particularly shoulder abduction, and 4/5 hip flexion, knee flexion/extension in bilateral lower extremities.

Labs:

- CBC: 34.0/11.8/35.7/216

- Differential: 31 bands

- INR: 1.94

- BMP: 131/5.3/102/17/88/2.55/215

- LFT: AST 93, ALT 57, AP 237, TB 2.9, DB 1.9, Alb 1.4

- Lactate: 3.3

- UA: 47WBC, 5RBC

- Utox: Negative

- ESR: 83, CRP: 11.9

- HIV: Nonreactive

Radiology

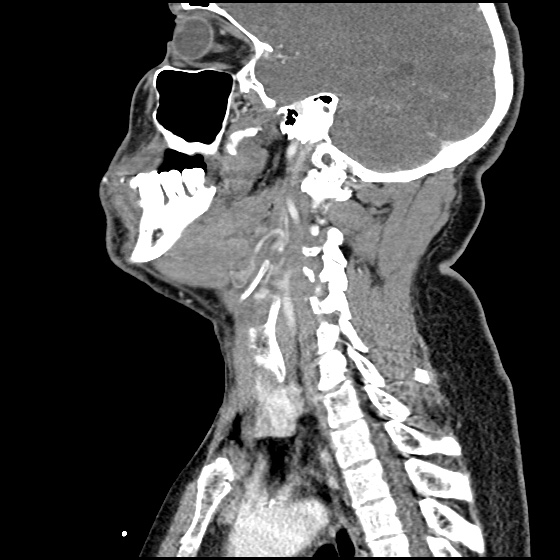

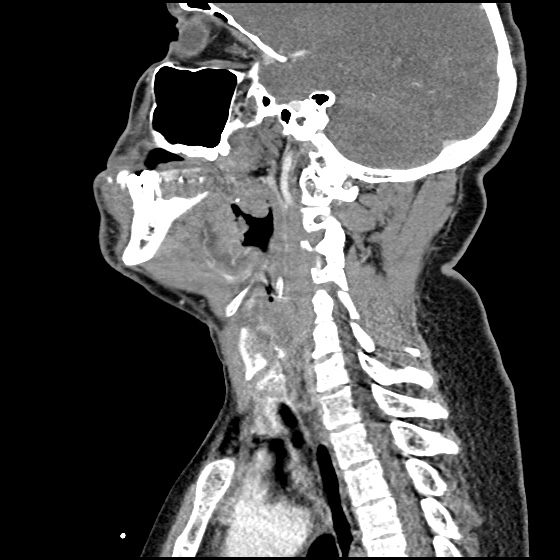

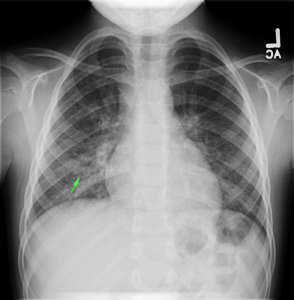

- CT head: Negative

- CXR: Negative

- XR Shoulder: Negative

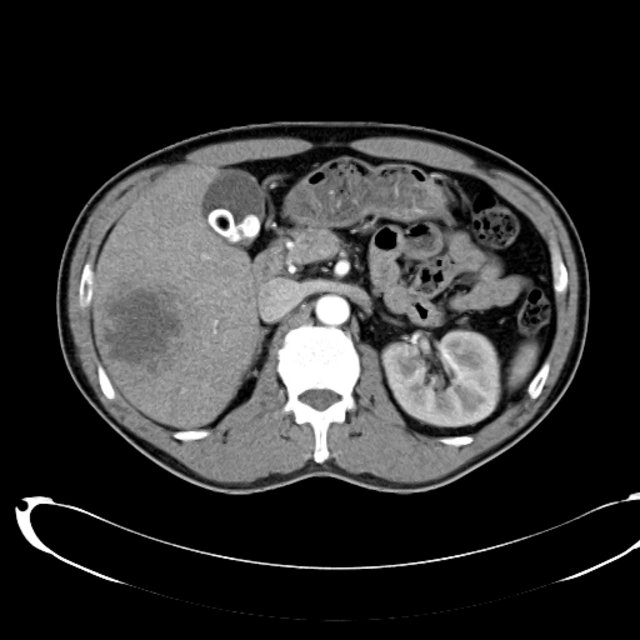

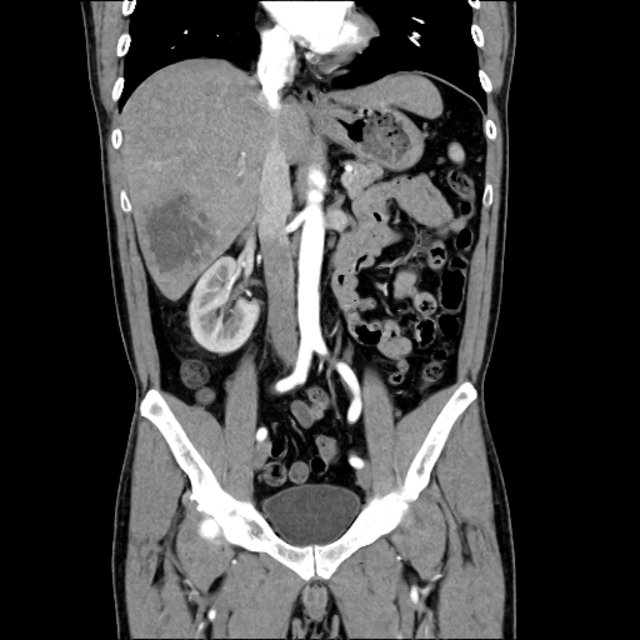

- CT Chest/Abdomen/Pelvis non-contrast: Mild bilateral hydrouereter/hyndronephrosis, L4-L5 grade 2 anterolisthesis.

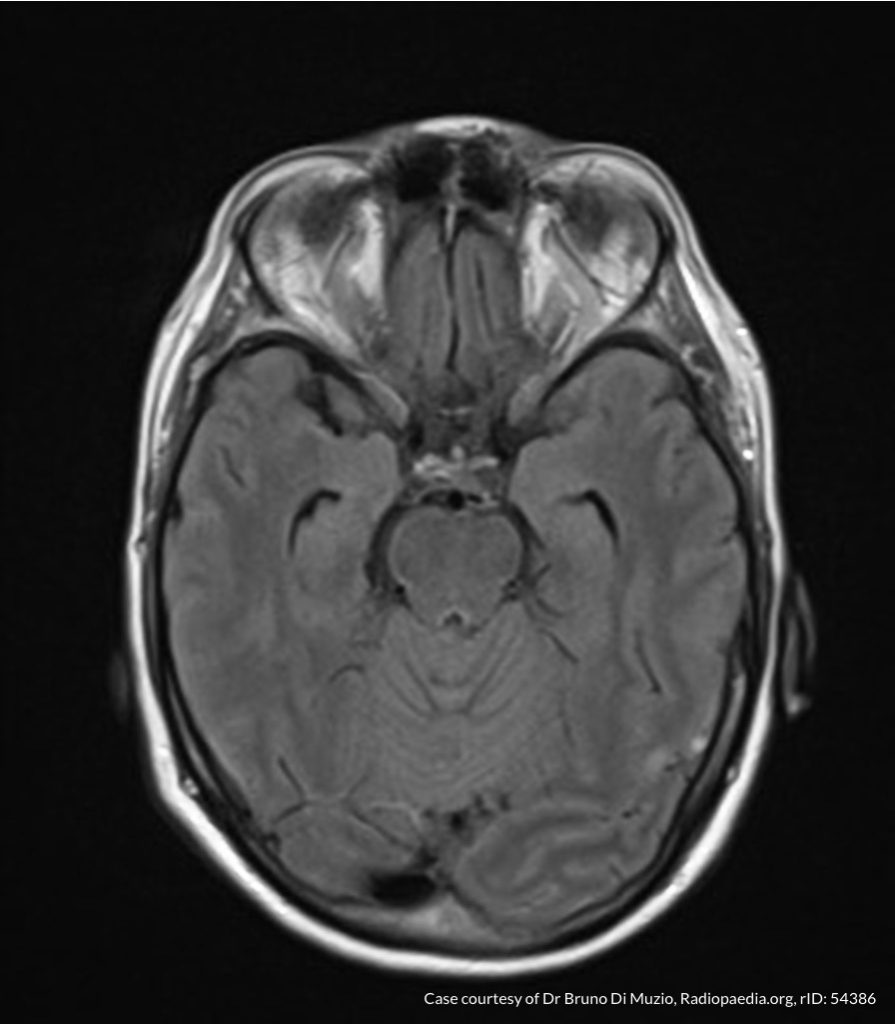

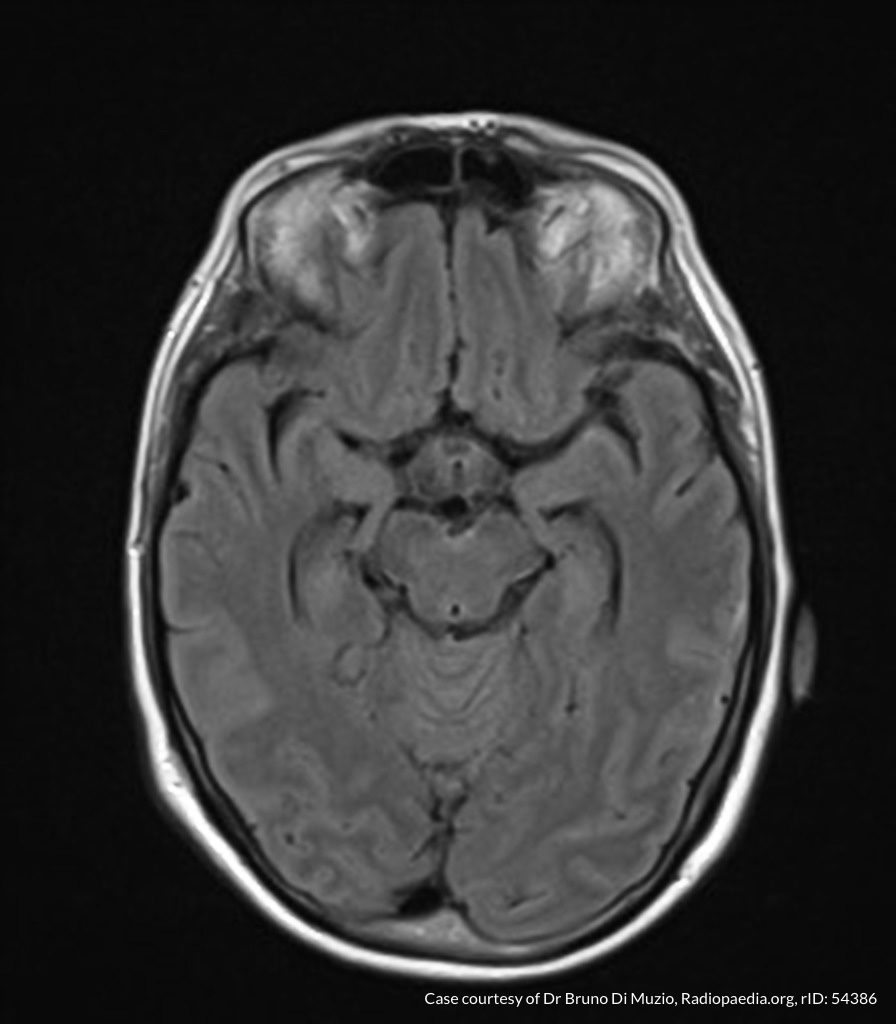

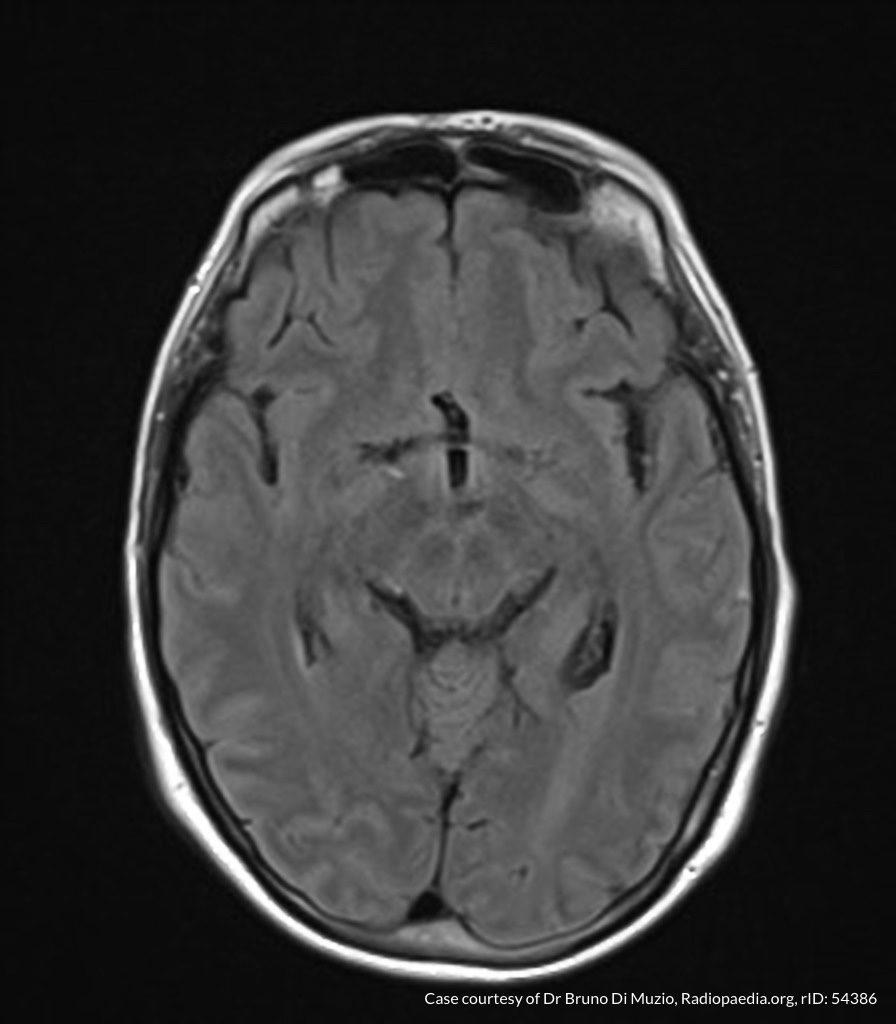

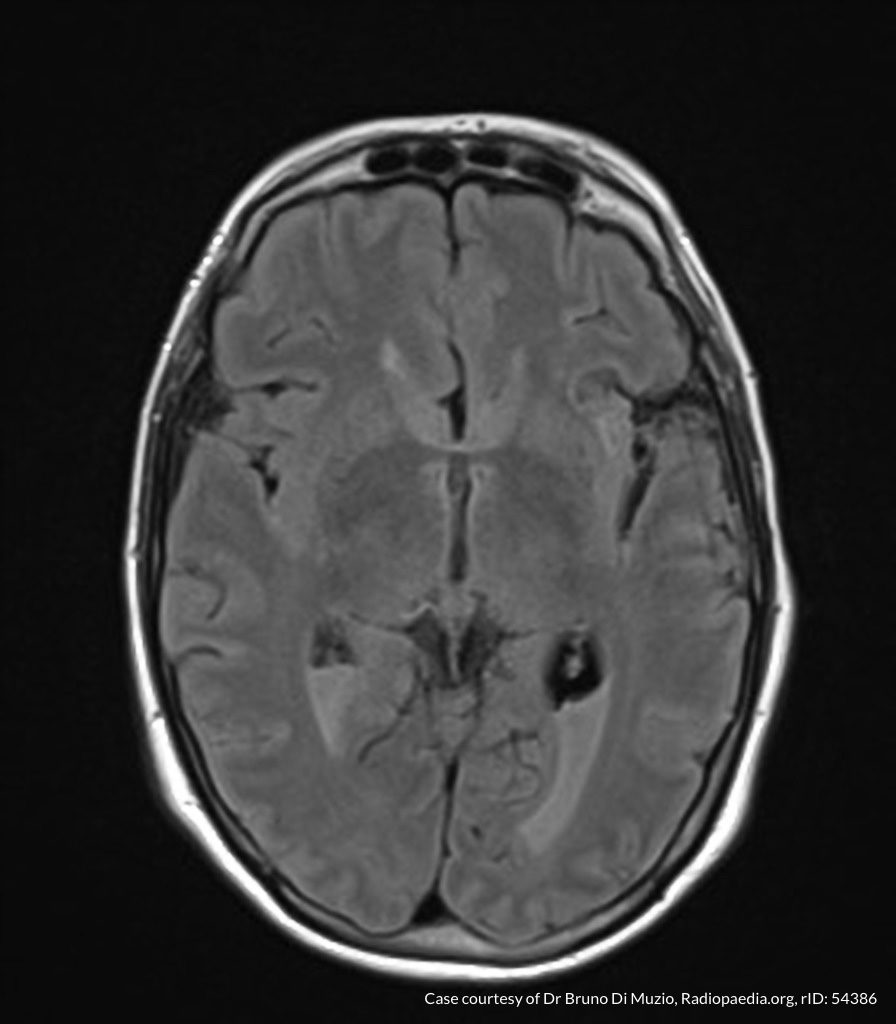

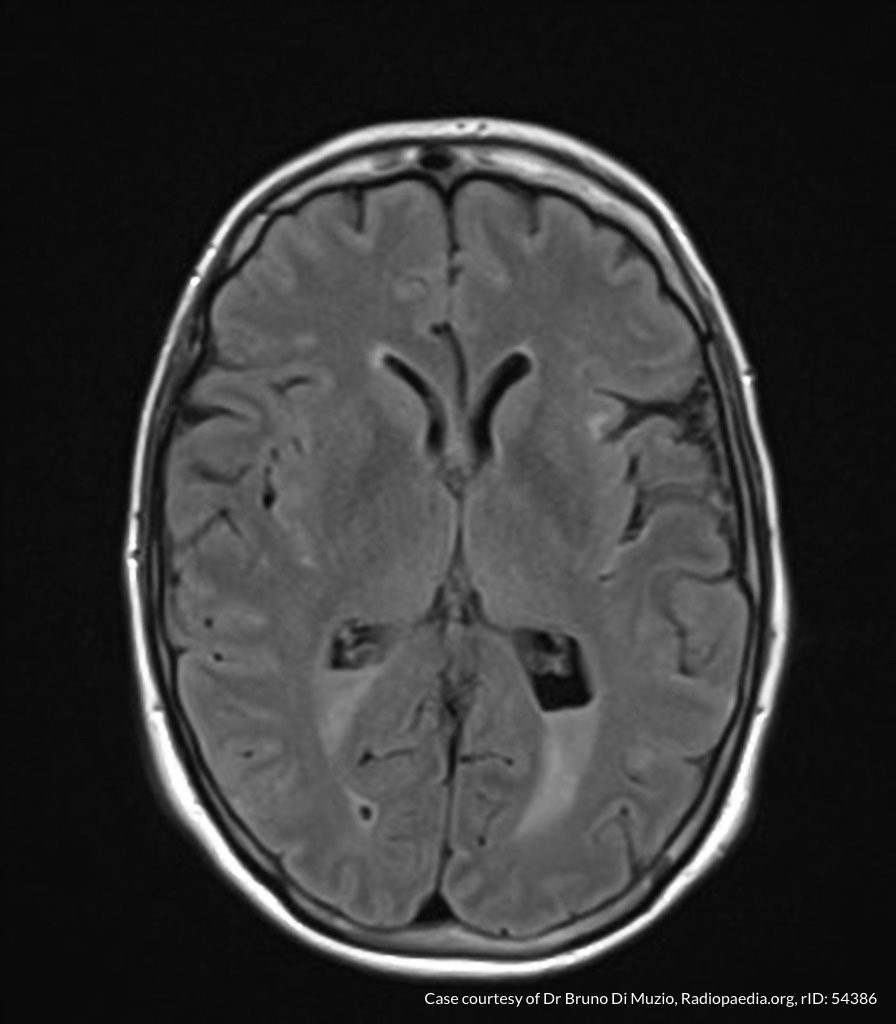

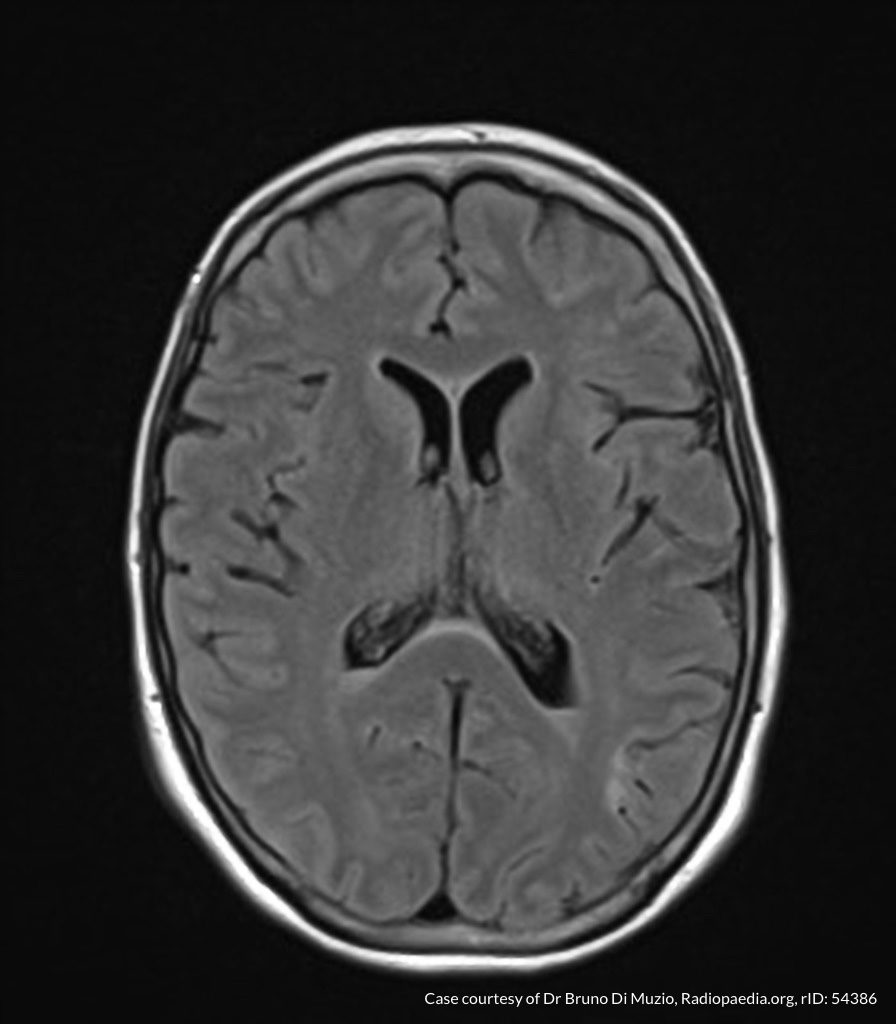

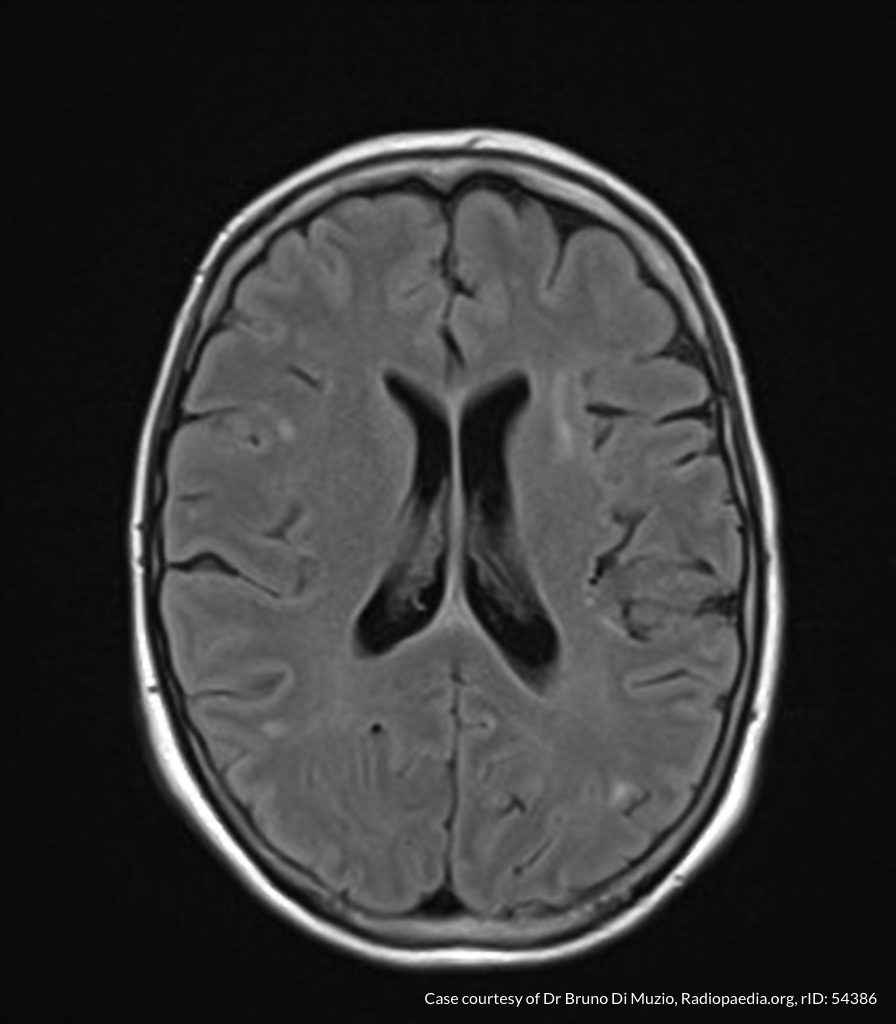

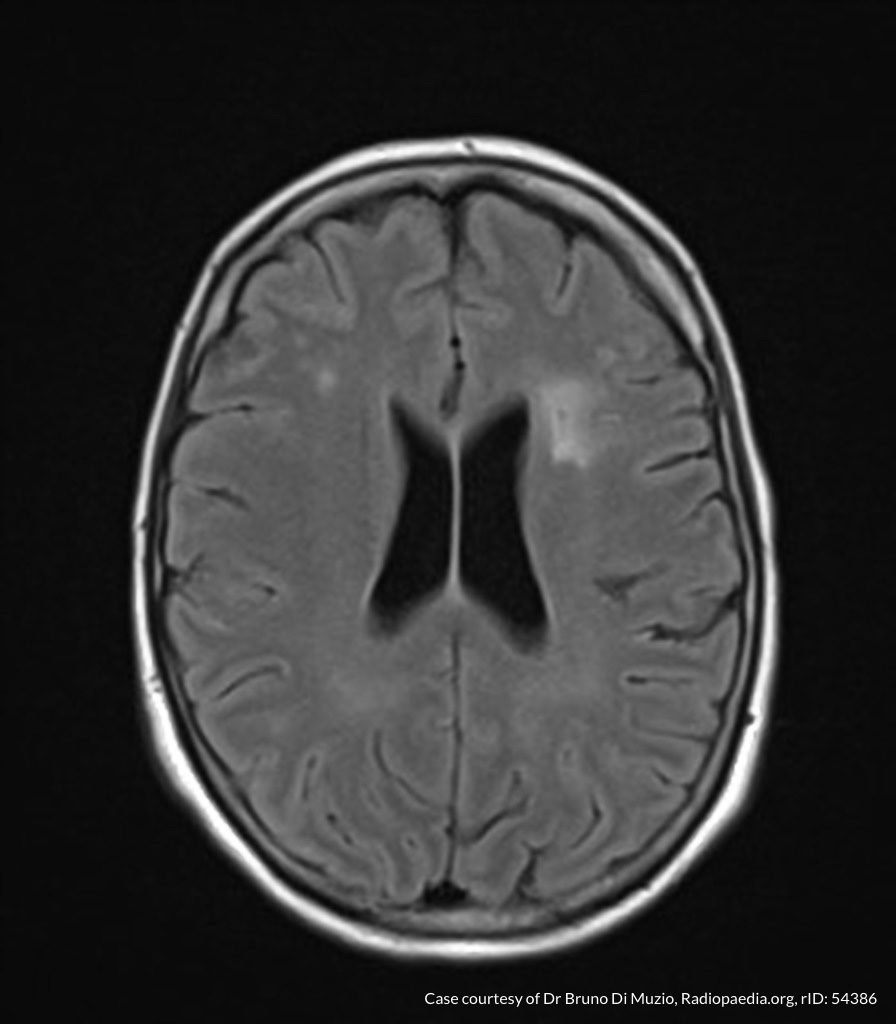

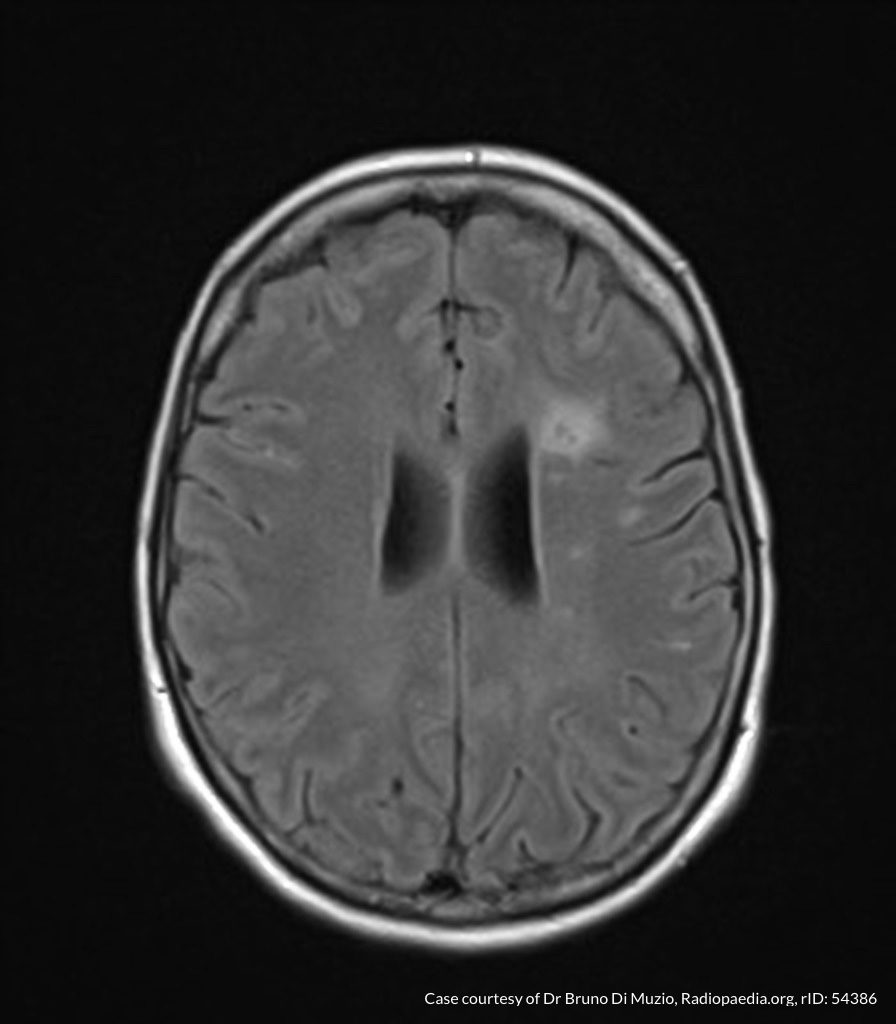

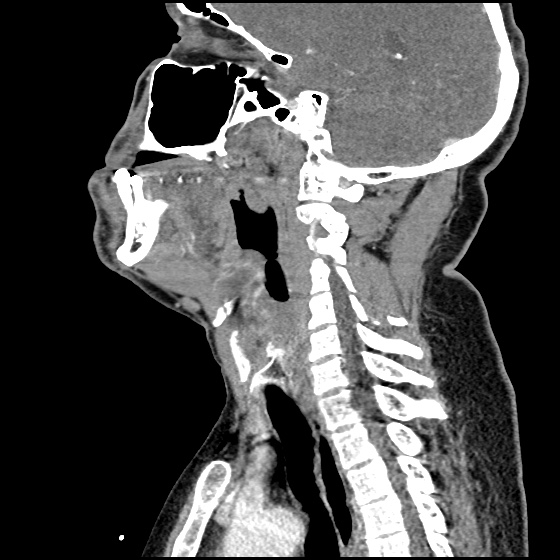

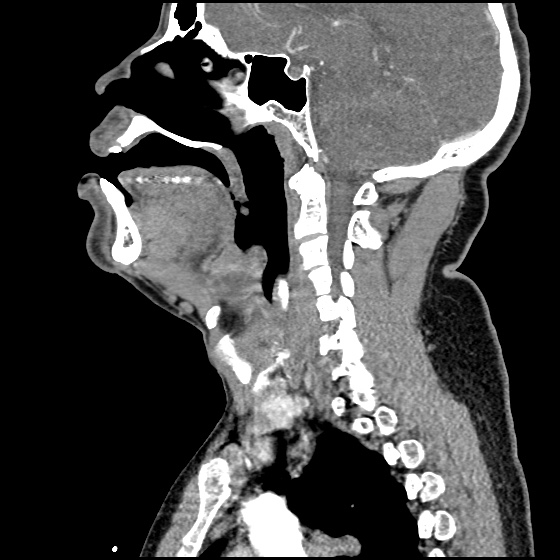

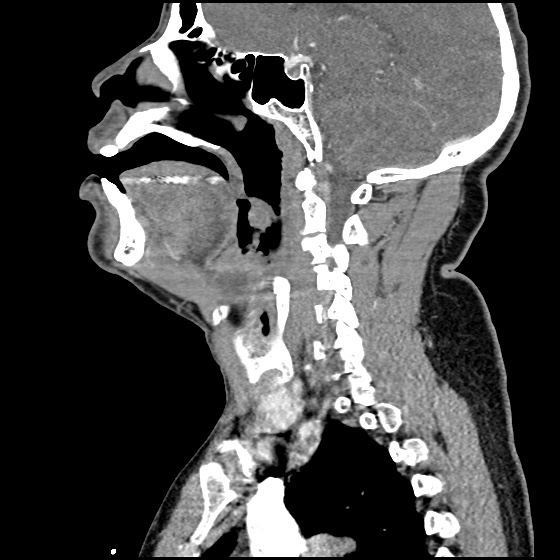

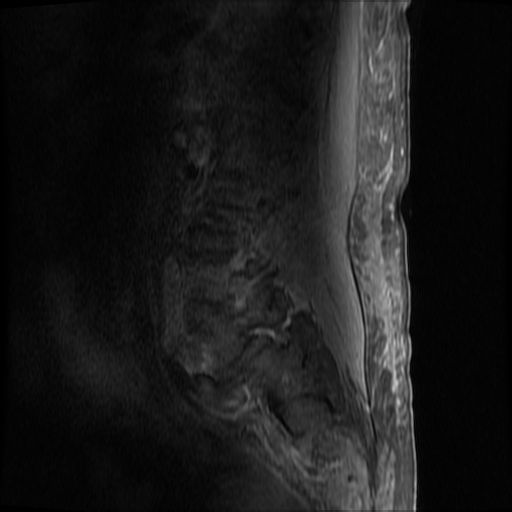

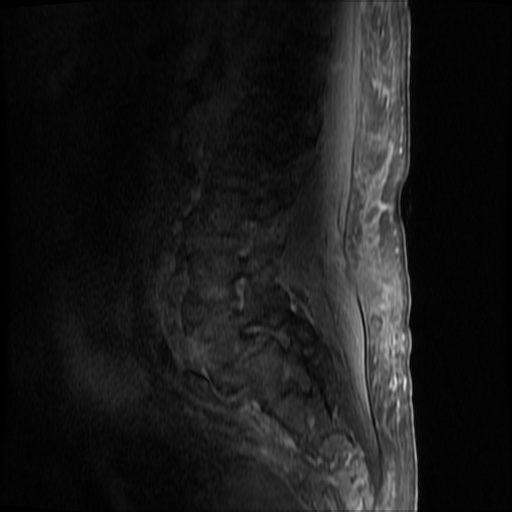

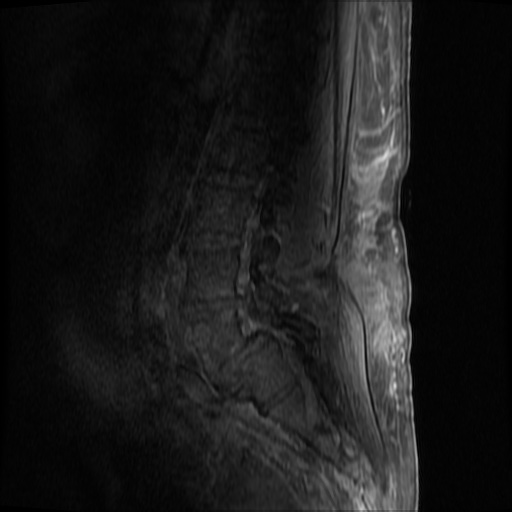

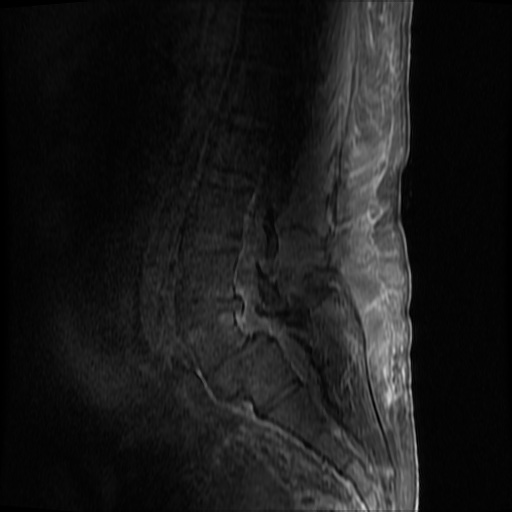

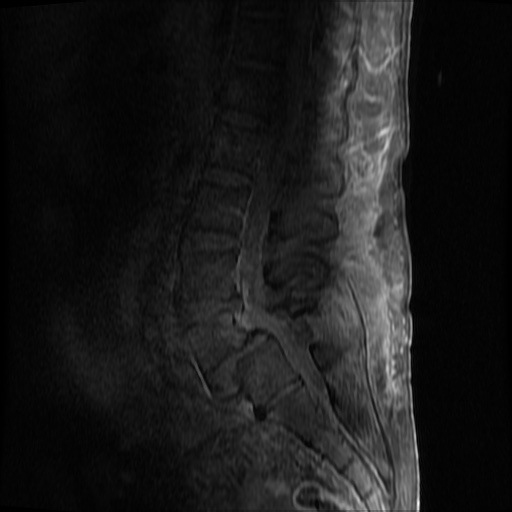

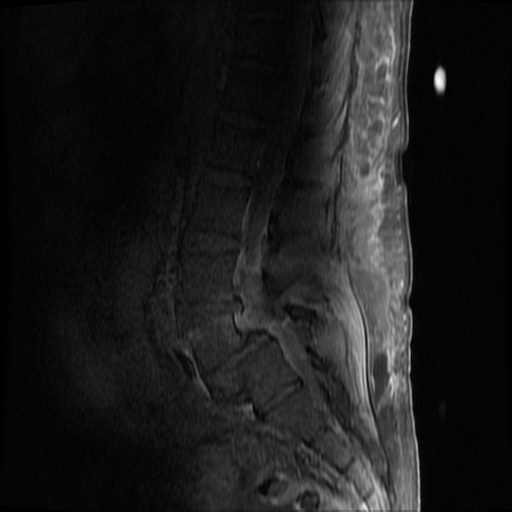

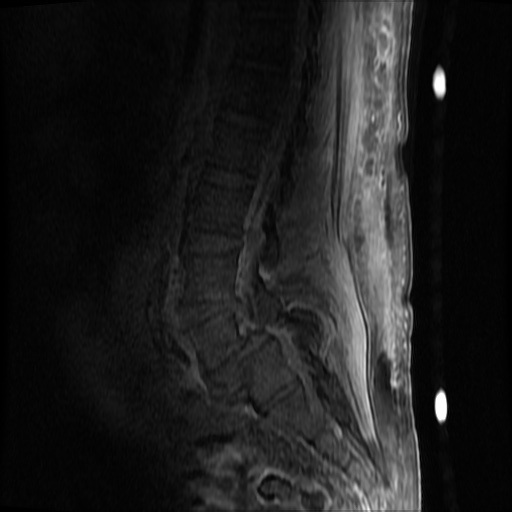

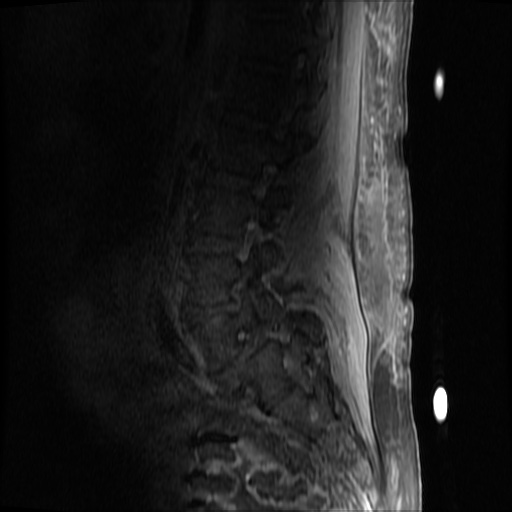

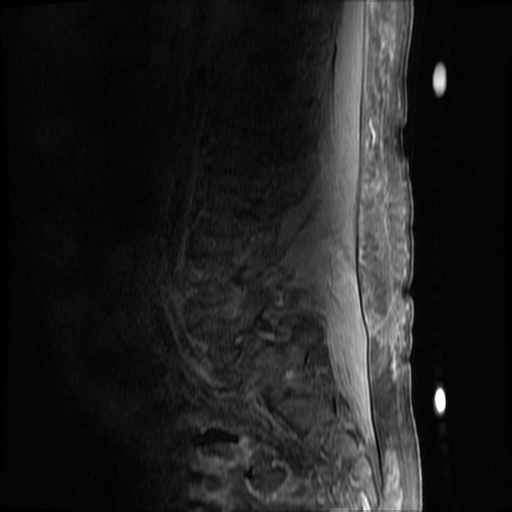

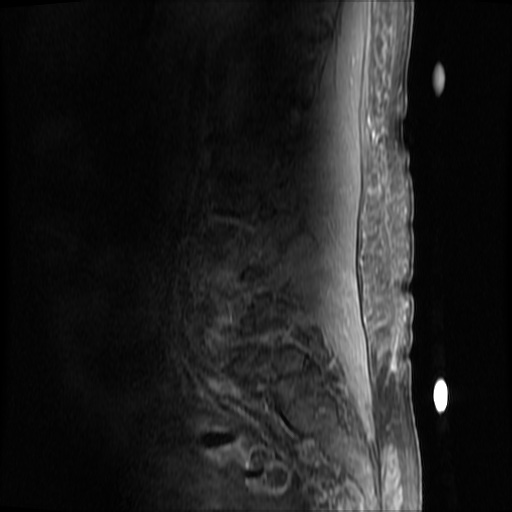

MRI Lumbar Spine w/contrast

Diffuse epidural enhancement posterior to the L4 and L5 vertebral bodies compressing the thecal sac and resulting in moderate severe spinal canal stenosis. Rim enhancement of the 1.5 cm left paraspinal fluid that may be within the L4 tendon sheath or simply paraspinal abscess.

Assessment/Plan:

Severe sepsis with end-organ dysfunction, unclear source (urinary tract involvement unlikely to account for severity of illness). Covered empirically with broad-spectrum anti-microbials including CNS infection given component of encephalitis. Admitted to the intensive care unit.

Hospital Course:

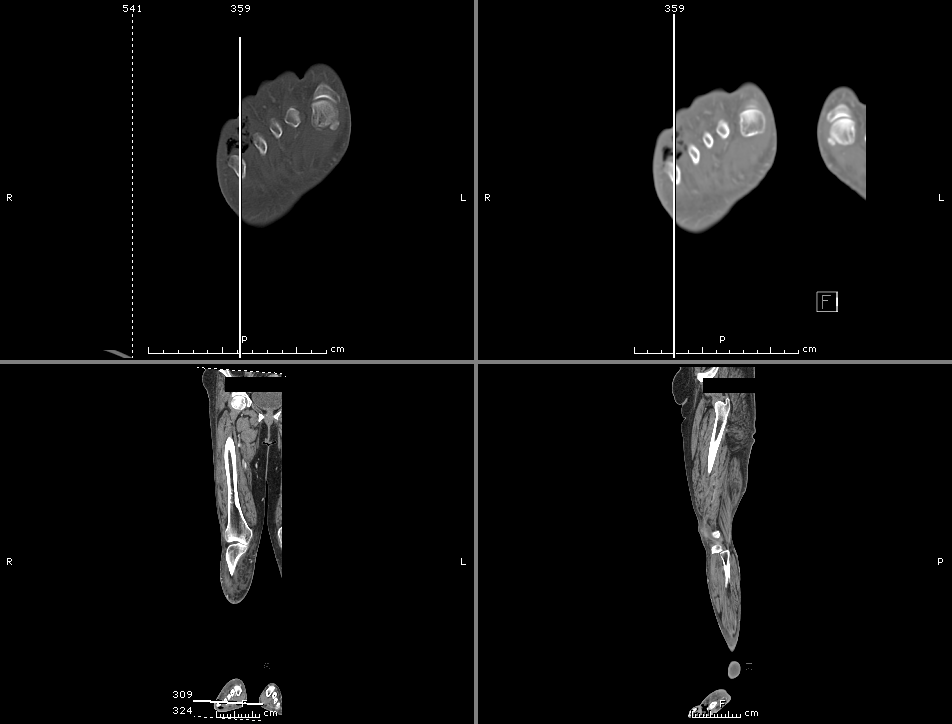

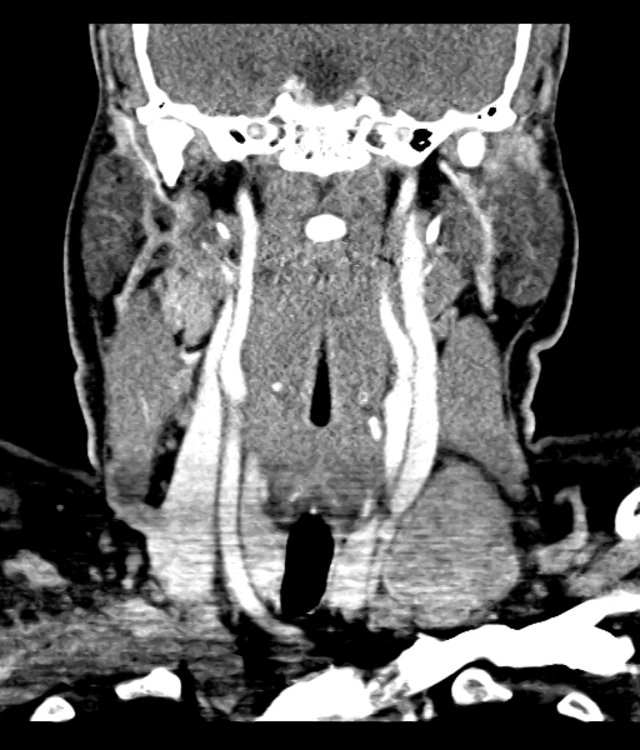

On hospital day 1, the patient underwent non-contrast MRI of the entire neuraxis with findings concerning for L4-L5 and L5-S1 epidural and paraspinal infection resulting in moderate-severe spinal canal stenosis. Blood and urine cultures grew gram-positive cocci in clusters.

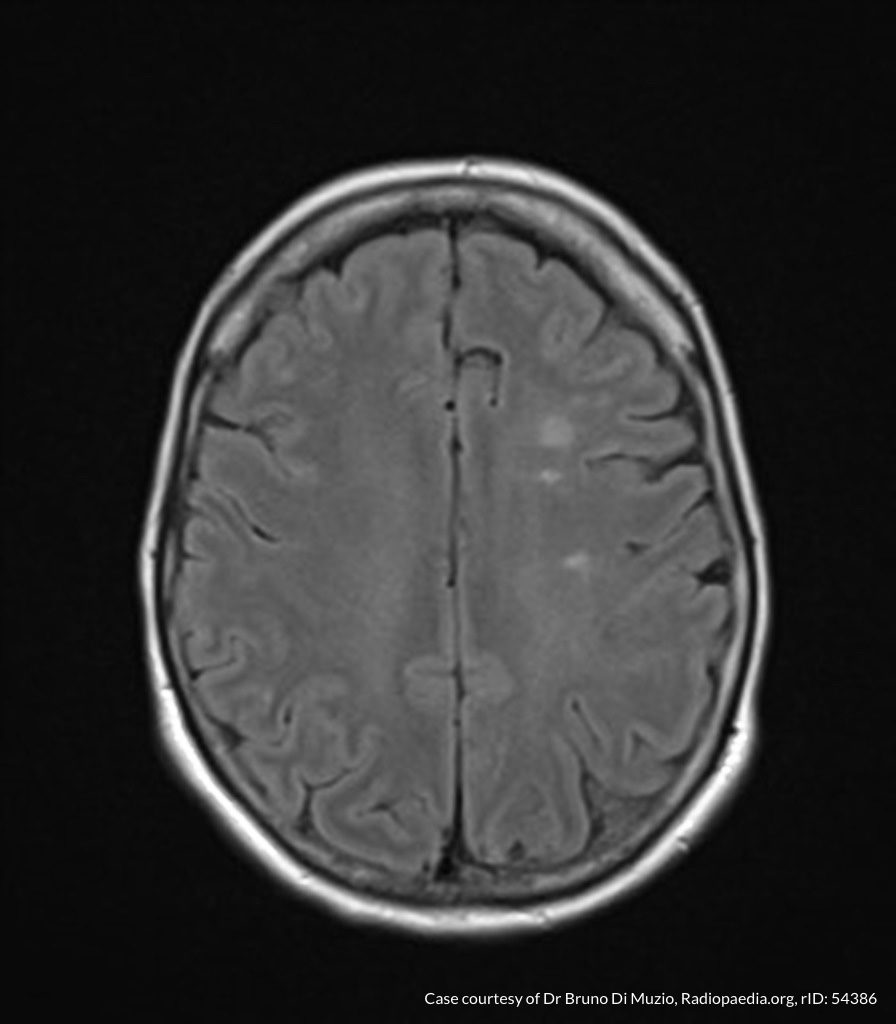

On hospital day 2, the patient became increasingly somnolent. Repeat examination by consulting neurology service was concerning for evidence of meningeal irritation. Cultures speciated as methicillin-sensitive staphylococcus aureus and oxacillin was added. MRI was repeated with gadolinium, findings concerning for L4 epidural vs. paraspinal abscess.

On hospital day 3, the patient’s mental status continued to worsen and he was intubated for airway protection. Neurosurgical intervention was deferred due to deteriorating clinical status. Shoulder synovial fluid aspirate culture positive for MSSA, orthopedic surgery consulted for washout/serial arthrocentesis. TTE performed without evidence of valvular vegetation.

On hospital day 4, additional warm joints were aspirated by orthopedic surgery including knee, bilateral ankles, and shoulder each of which ultimately grew MSSA.

On hospital day 6, the patient underwent OR washout of affected joints with intraoperative findings of purulent fluid. TEE performed without evidence of valvular vegetation. The following day, underwent fluoroscopically-guided lumbar puncture, CSF studies inconclusive. Rifampin added for high-grade bacteremia with multiple seeded sites.

The patient was extubated on hospital day 9 and transferred out of the intensive care unit. The following day, he became increasingly tachypneic with evidence of volume overload on examination and was intubated and returned to the intensive care unit. Sustained PEA arrest post-intubation with ROSC, possibly secondary to pneumothorax vs. hypoxia from extensive mucous plugging. Required increasing vasopressor support over the subsequent 12 hours, emergent CVVHD for worsening academia and hypervolemia. The patient sustained another arrest and ultimately expired.

The final impression was that of high-grade bacteremia from unclear source (vague history of proximate hand laceration/infection) with resultant seeding of epidural/paraspinal space, urinary tract, multiple joints, and likely CNS/meninges. Review of abdominal ultrasonography with evidence of cirrhosis, suggesting that some component of initial hepatic synthetic dysfunction may have been chronic and this may have increased the patient’s risk for disseminated infection and SEA. Neurosurgical intervention was not pursued due to unstable clinical status and as the patient’s neurological findings were not consistent with the location of the identified lesion.

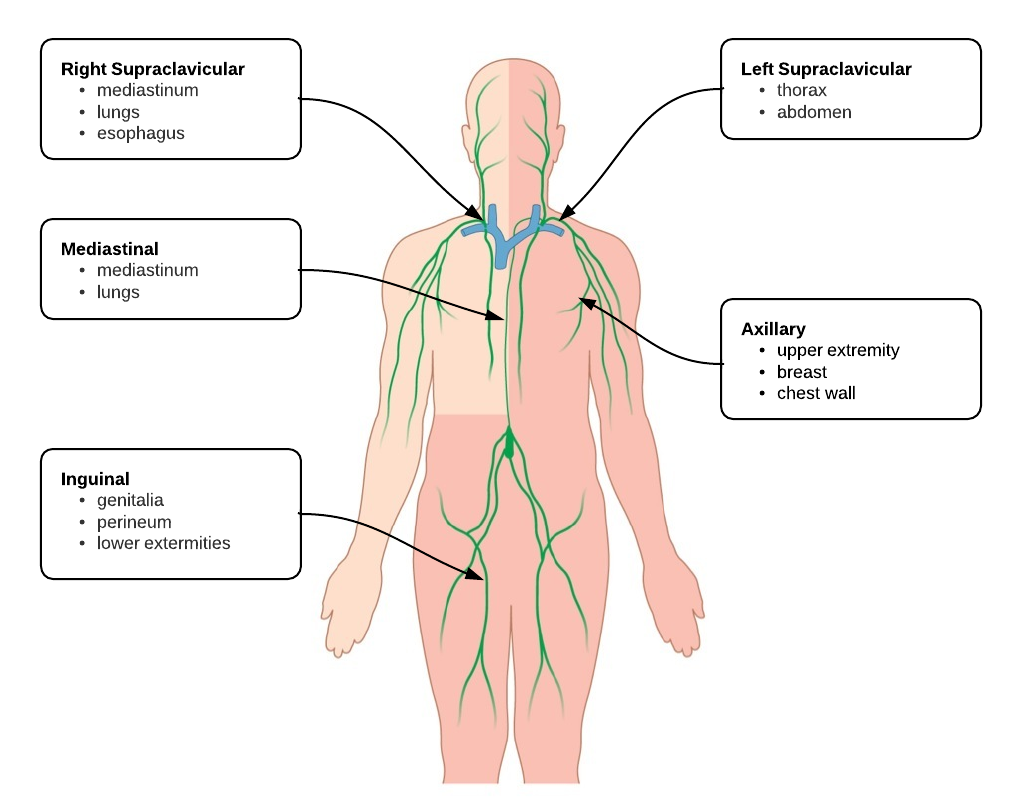

Spinal Epidural Abscess (SEA)1

Risk factors:

- Immunocompromise: diabetes, cirrhosis, CKD, HIV/AIDS

- Anatomic: DJD, trauma, prior surgery

- Introduction: IVDA, epidural anesthesia, tattoo

Organism:

- S. aureus, 2/3

- S. epidermidis (associated with device, instrumentation)

- E. coli (urine spread)

- P. aeruginosa (IVDA)

- Rare: anaerobes, mycobacteria, fungi

Staging:

- Back pain at affected site

- Nerve root pain from affected level

- Weakness, sensory deficit, bladder/bowel dysfunction

- Paralysis

Clinical features:

- Back pain (75%)

- Fever (50%)

- Neuro deficit (33%)

Diagnosis:

- Labs: Leukocytosis, ESR/CRP, blood cultures

- Imaging: MRI with gadolinium, 90% sensitivity

- Clinical findings and laboratory studies are insensitive and non-specific, in one study, approximately ½ of patients had >2 visits.

Prevalence of abnormal physical findings 2

| Finding |

Prevalence |

| Fever (T>38°C) |

19-32% |

| Focal spinal TTP |

52-62% |

| Diffuse spinal TTP |

63-65% |

| Positive SLR |

11-13% |

| Abnormal sensation |

17-27% |

| Weakness |

29-40% |

| Abnormal reflexes |

8-17% |

| Abnormal rectal tone |

5-10% |

| Saddle anesthesia |

2% |

Clinical Decision Guideline 3

Management:

- Neurosurgical evacuation/fusion

- Antibiotics (vancomycin, oxacillin, cefepime)

- Neurosurgical intervention may not result in neurological recovery if symptoms present for > 24-36 hours and may be impractical in the setting of panspinal infection.

References:

- Darouiche RO. Spinal epidural abscess. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(19):2012–2020. doi:10.1056/NEJMra055111.

- Davis DP, Wold RM, Patel RJ, et al. The clinical presentation and impact of diagnostic delays on emergency department patients with spinal epidural abscess. J Emerg Med. 2004;26(3):285–291. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2003.11.013.

- Davis DP, Salazar A, Chan TC, Vilke GM. Prospective evaluation of a clinical decision guideline to diagnose spinal epidural abscess in patients who present to the emergency department with spine pain. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;14(6):765–770. doi:10.3171/2011.1.SPINE1091.

- WikEM: Epidural abscess (spinal)