HPI:

47 year-old female with a history of arthritis, gout and AVP (5/2013) resulting in tib/fib fracture s/p ORIF presenting with severe joint pain, worsening in the past week such that she has been unable to walk. While she reported significant diffuse joint pain, it was predominantly focused on her left leg, bilateral knees, and left shoulder. Joint pain progressively worsens over the course of the day and is worse with activity (better at rest). She reported occasional joint swelling, but no redness, fevers/chills, new trauma, recent travel, and is not sexually active. She reports suffering from joint pain for over 10 years, previously well-controlled with OTC pain medications (ibuprofen), however this had grown ineffective in the past week. She had been prescribed Norco after her surgery but was unable to afford it. She denies any recent intake of foods that have previously been triggers for acute gouty flares.

PSH:

- Left tib/fib fracture s/p ORIF

FH:

- No family history of RA, SLE or joint disease.

SHx:

- No t/e/d use

- Lives at home alone

Meds:

- Ibuprofen 800mg p.o. p.r.n. pain

Physical Exam:

| VS: |

T 98.1 HR 109 RR 18 BP 108/66 O2 95% RA |

| Gen: |

Thin female, appearing older than her stated age, in significant pain when helped to transfer to bed for examination |

| HEENT: |

PERRL, MMM, no lesions |

| CV: |

RRR, normal S1/S2, no M/R/G |

| Lungs: |

CTAB, no crackles/wheezing |

| Abd: |

+BS, soft, NT/ND, no masses |

| Ext: |

Knees appear symmetric, no deformities, no erythema or warmth to touch, no effusion detected, significant tenderness to light touch of bilateral knees. Significant decreased ROM 2/2 pain in b/l lower extremities, limited to 30 degrees of knee flexion, unable to test strength 2/2 pain.Left lower extremity with 6cm longitudinal incisions on lateral and medial aspects of leg. Incisions appear well-healed without erythema/discharge. Decreased sensation on lateral and medial aspects of left leg.

Left shoulder appears normal, no obvious deformities, no bony tenderness. Decreased ROM to 15 degrees of abduction/flexion/extension 2/2 pain. |

| Neuro: |

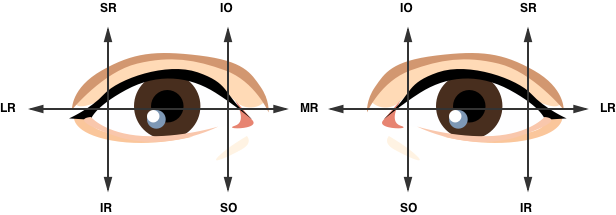

AAOx4, CN II-XII intact, gait not tested. A high-frequency, high-amplitude tremor is noted in the bilateral upper extremities at rest and with activity. Tremor appears associated with patient’s distress and pain. |

Labs/Studies:

- CBC: 9.4/12.8/38.1/311

- BMP: 135/3.9/100/27/14/0.60/113

- CRP: 0.18

- ESRW: 20

- Uric Acid: 2.6

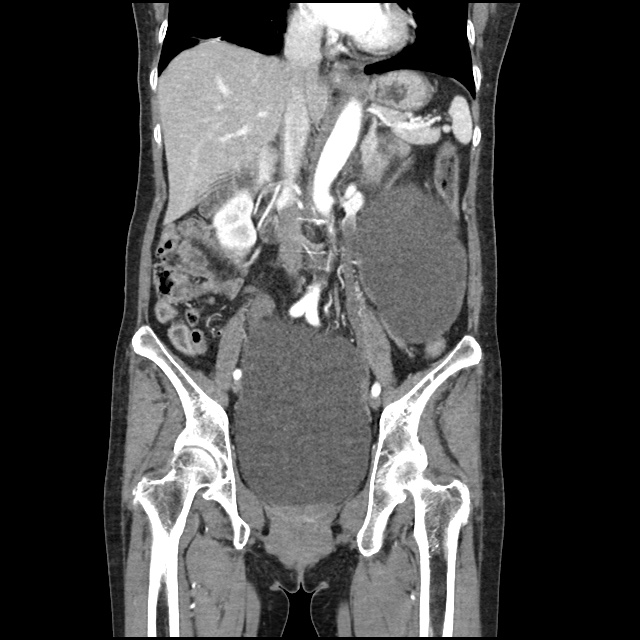

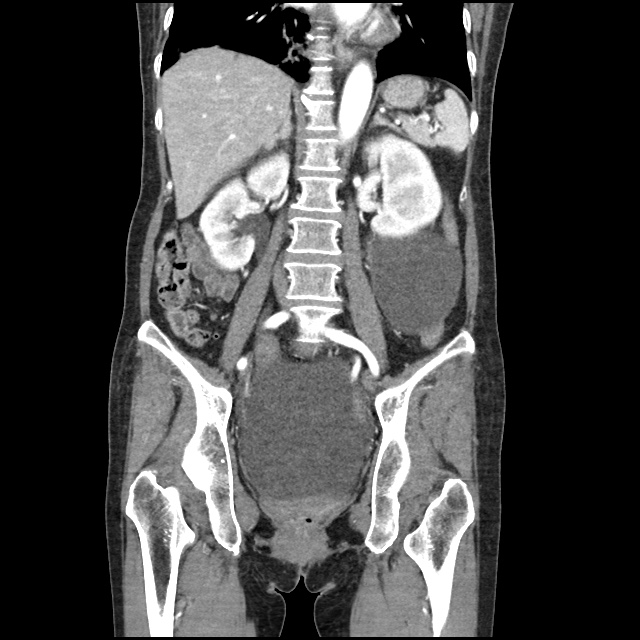

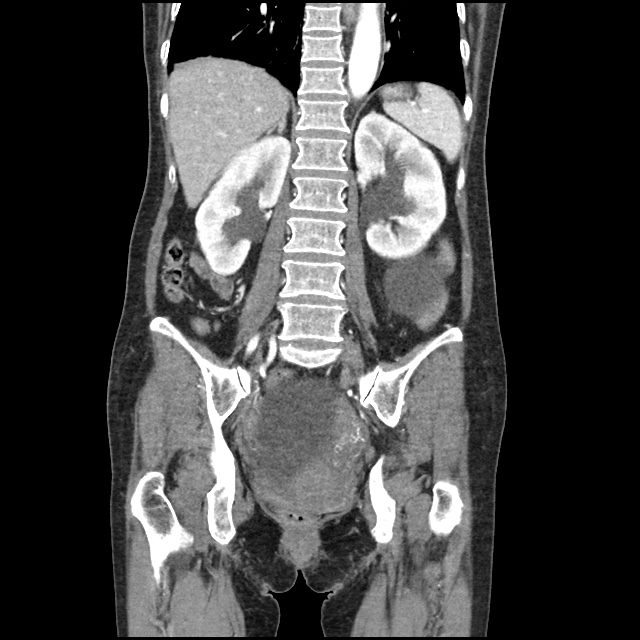

- XR Left Tibia/Fibula: There is a metallic fixation device noted in the tibia. There is no evidence of loosening of the metallic components. The bones appear to be in gross anatomic alignment.

Assessment/Plan:

47F w/hx arthritis, gout, recent tib/fib fx s/p ORIF presenting with worsening polyarticular arthralgia unresponsive to OTC medications admitted for evaluation and pain management.

# Polyarticular arthralgia: Multiple joints affected, however patient notes most significant in bilateral knees and recently operated left leg. Polyarticular involvement, symmetric distribution and predominant involvement of large joints is suggestive of osteoarthritis. Also, given patient’s significant distress and multiple points of tenderness, potential extra-articular cause such as complex regional pain syndrome. Unlikely inflammatory arthritis (infectious, crystal arthropathy, rheumatic disease) given distribution and no significant erythema, warmth or effusion which could be aspirated. Obtained imaging of LLE to evaluate recent surgical repair of tib/fib fracture, with no evidence of loosening of fixation components or misalignment. Patient’s symptoms improved with morphine 5mg i.v. x2 in ED. Will admit for continued evaluation and pain management, consider addition of gabapentin for potential neuropathic pain associated with recent surgery.

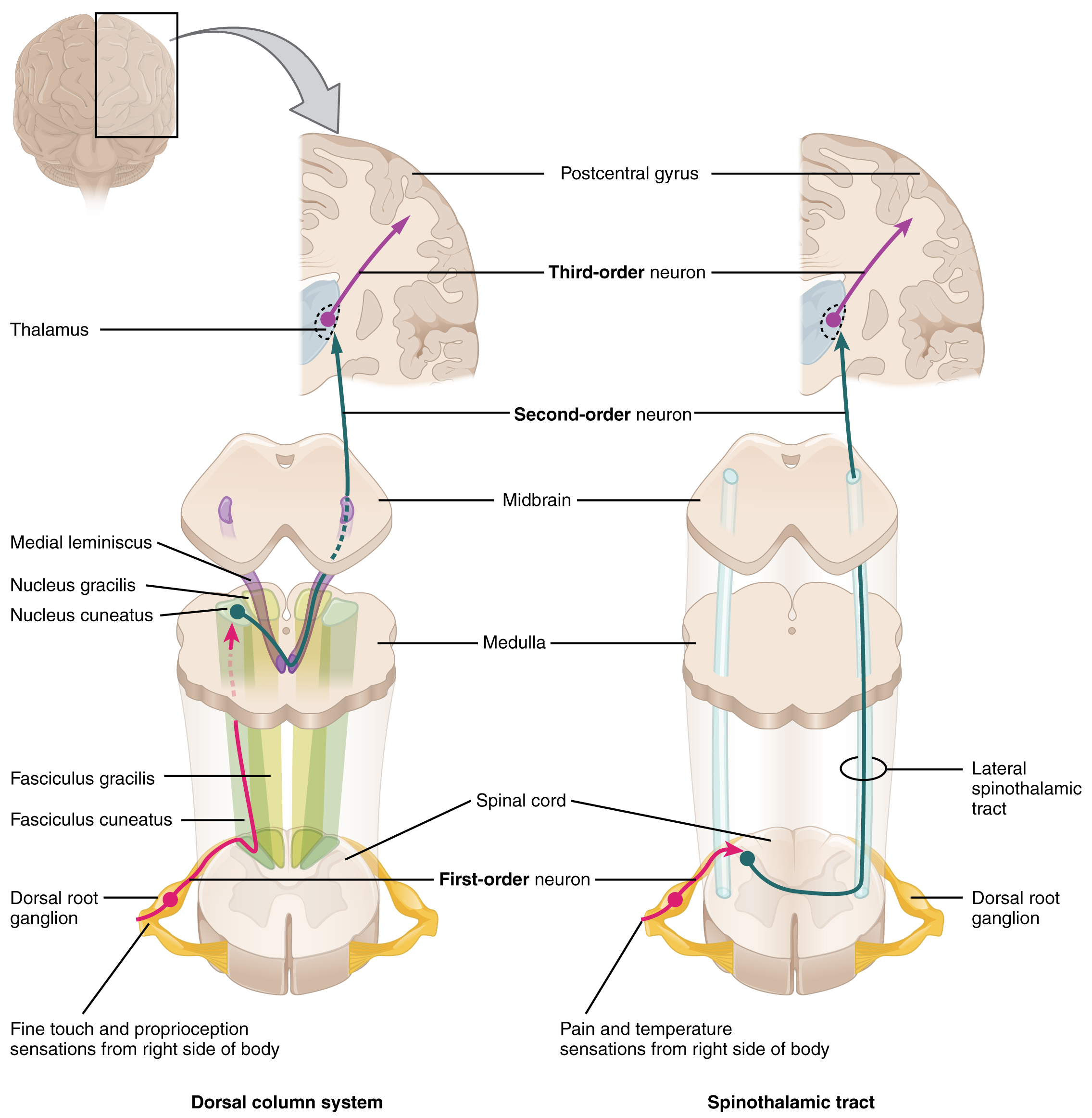

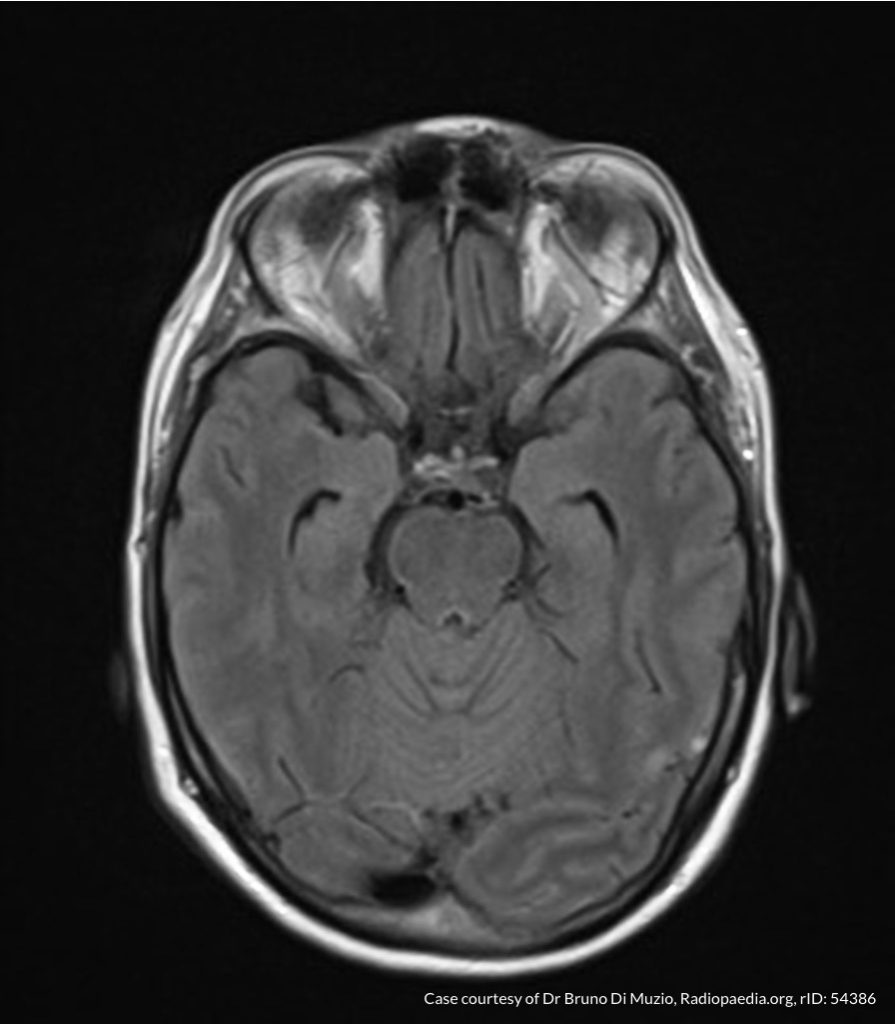

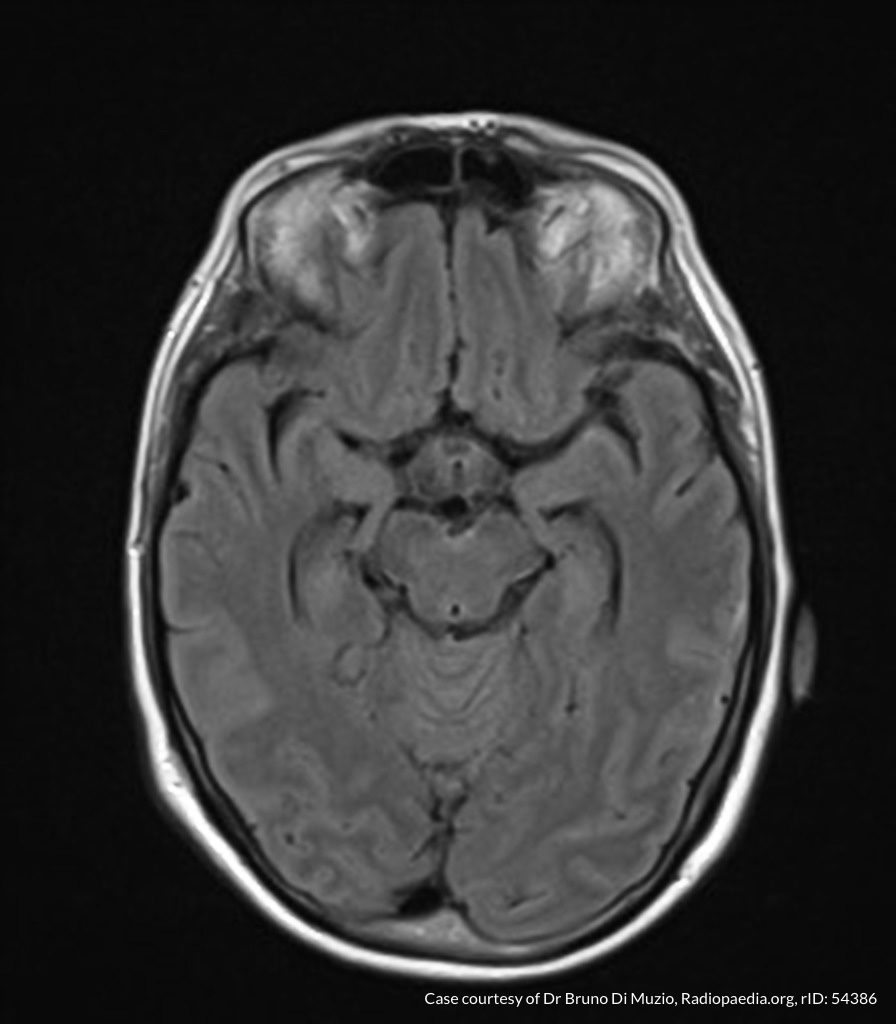

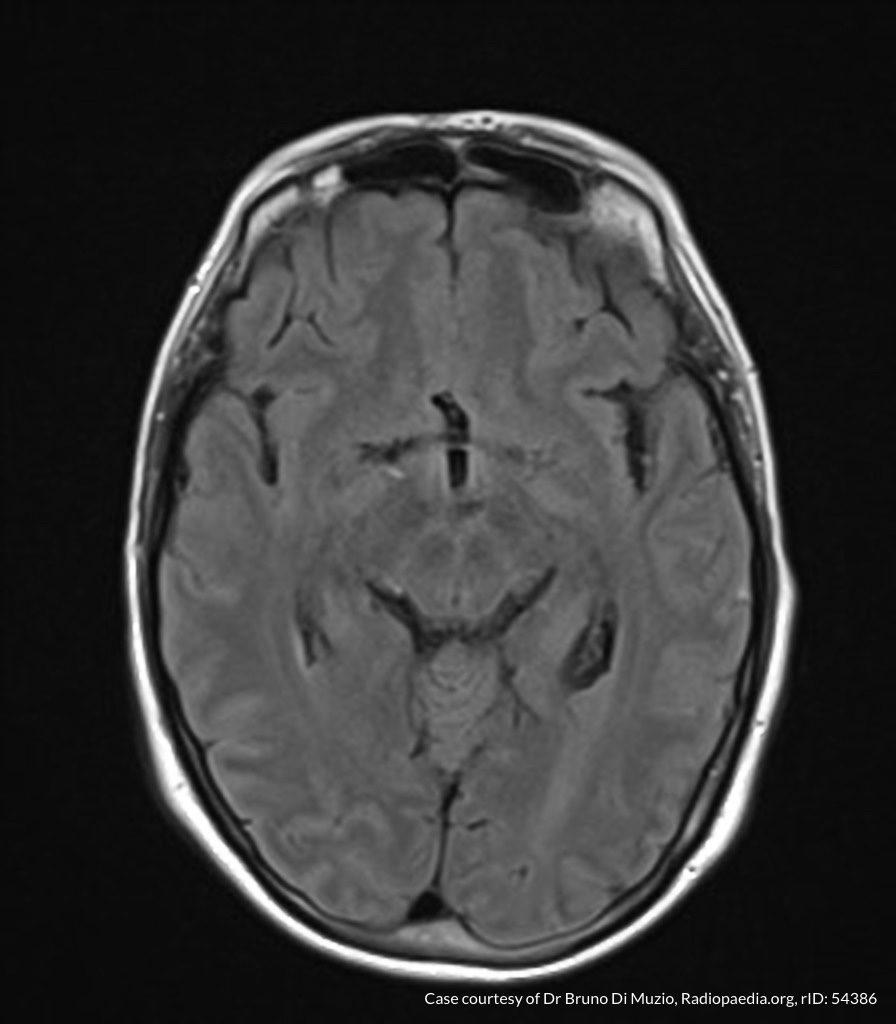

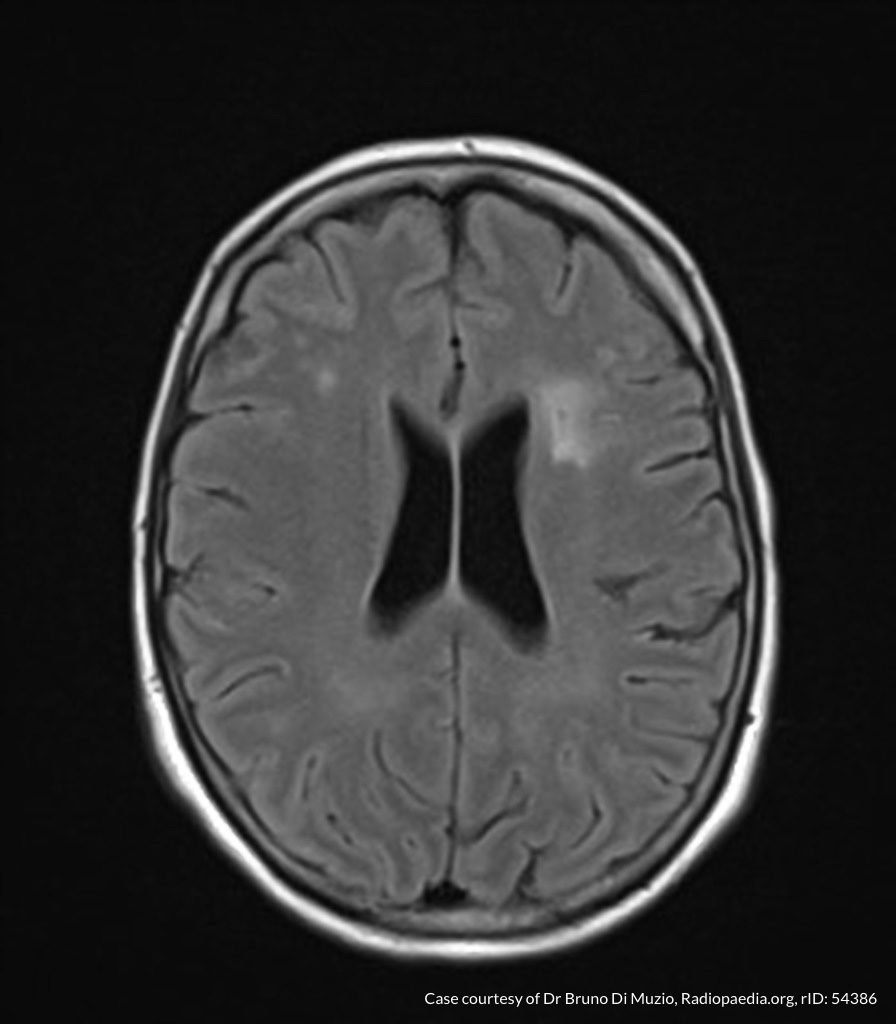

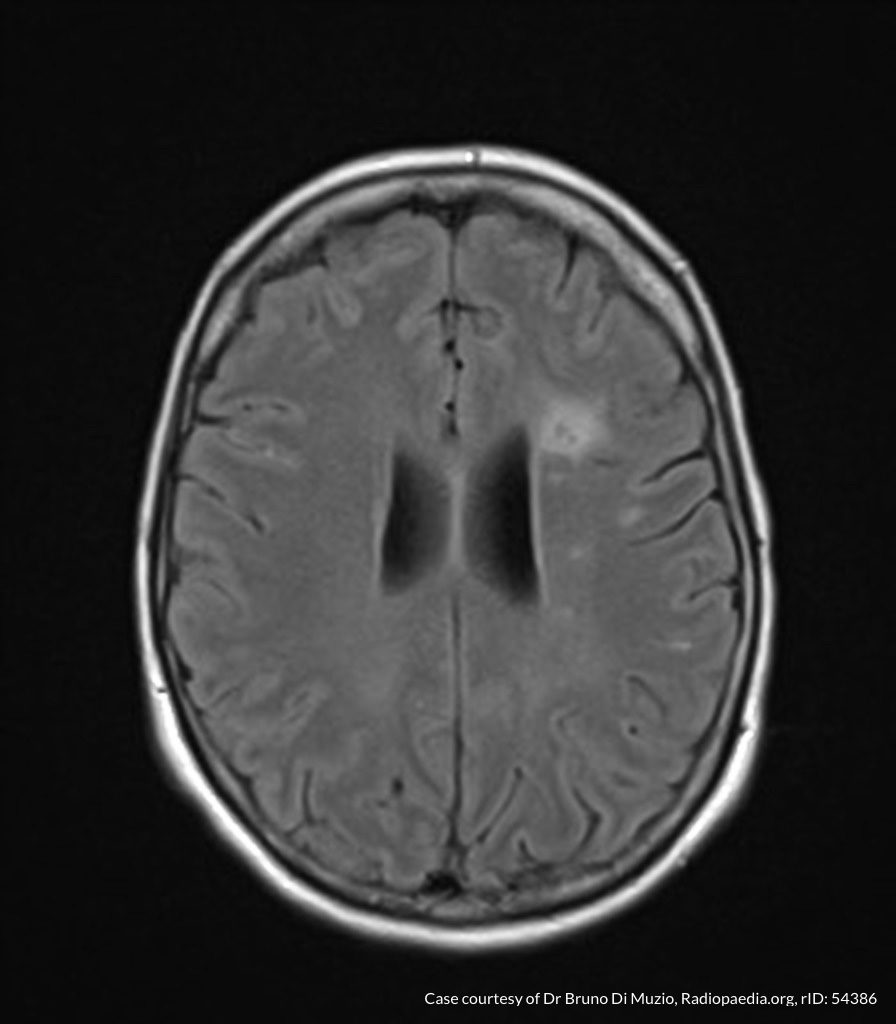

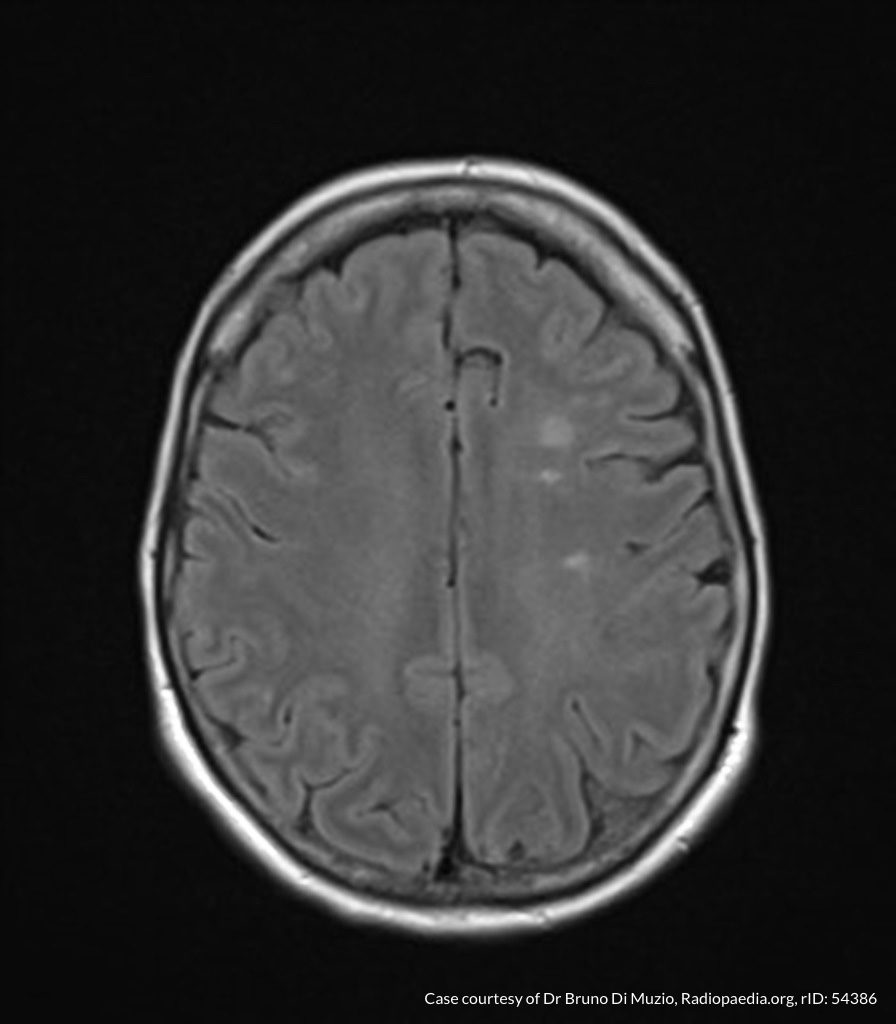

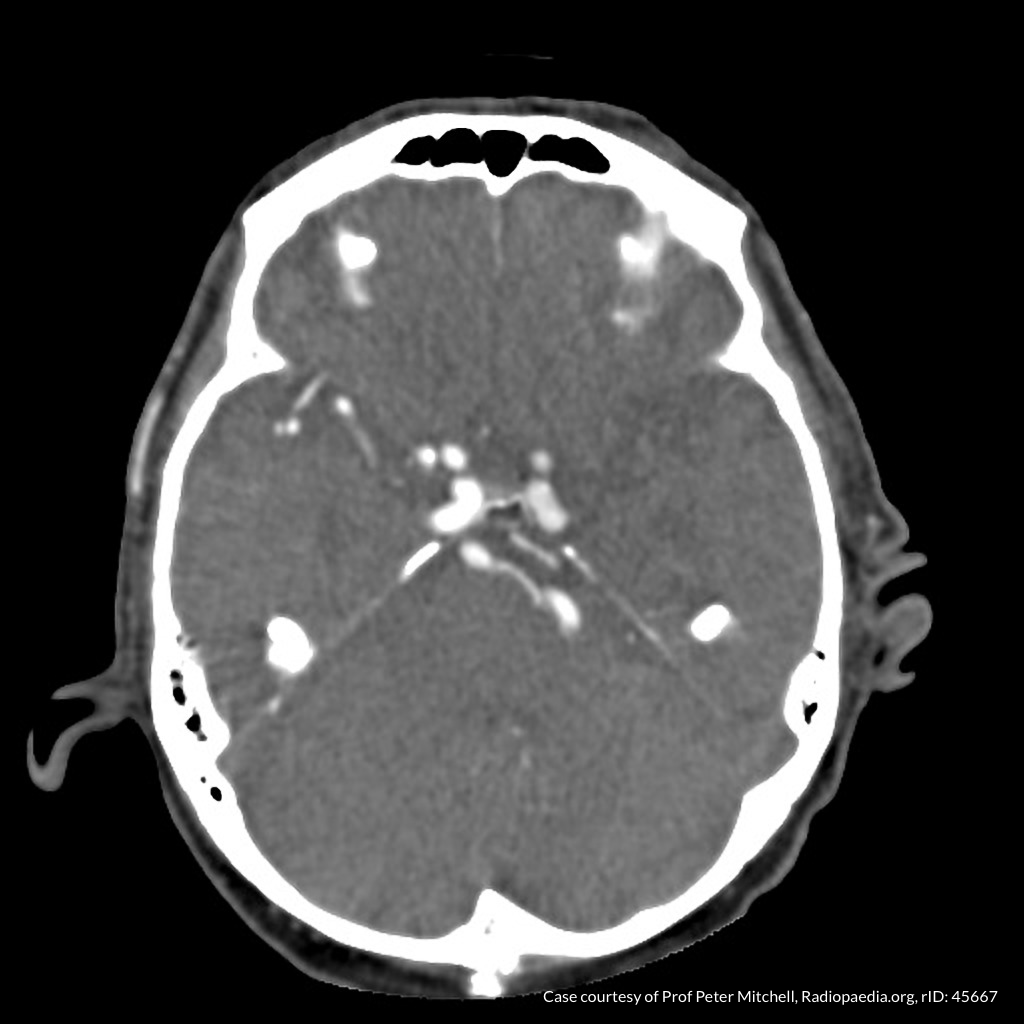

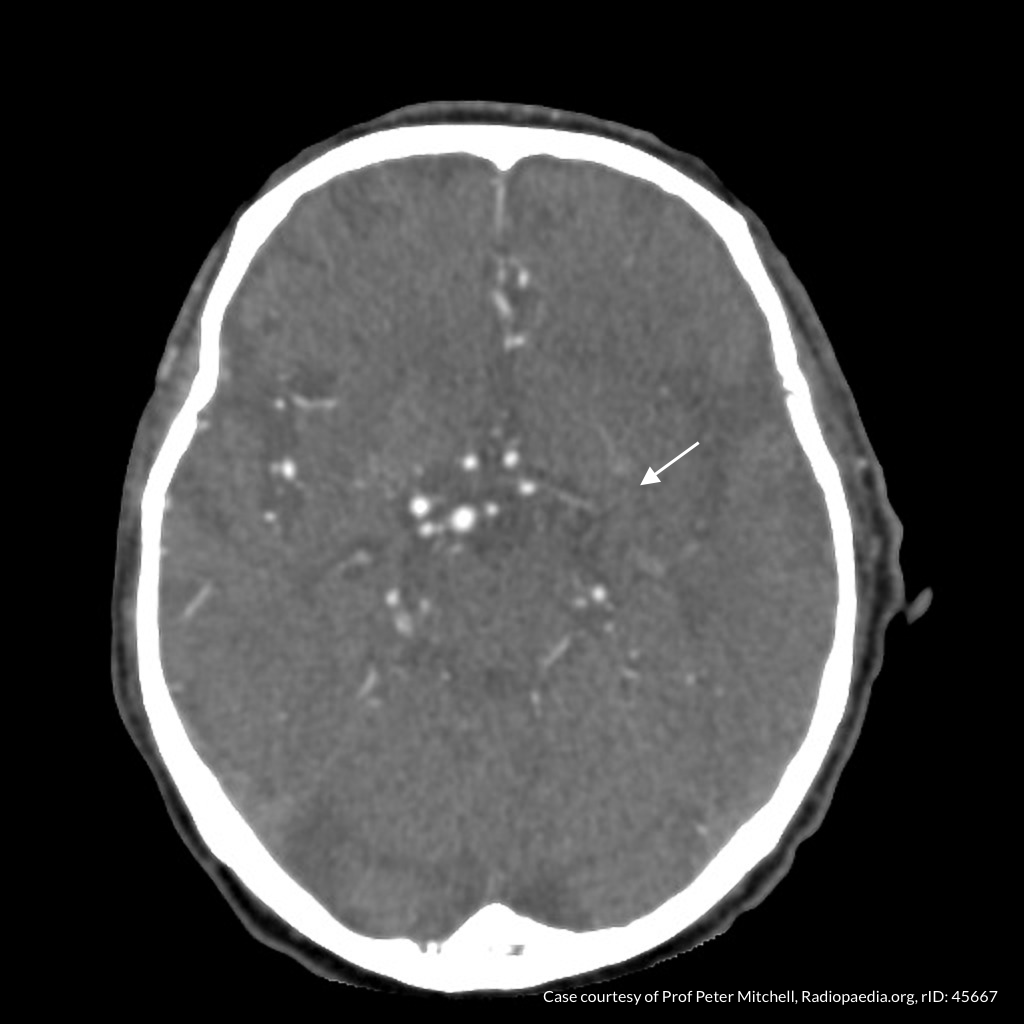

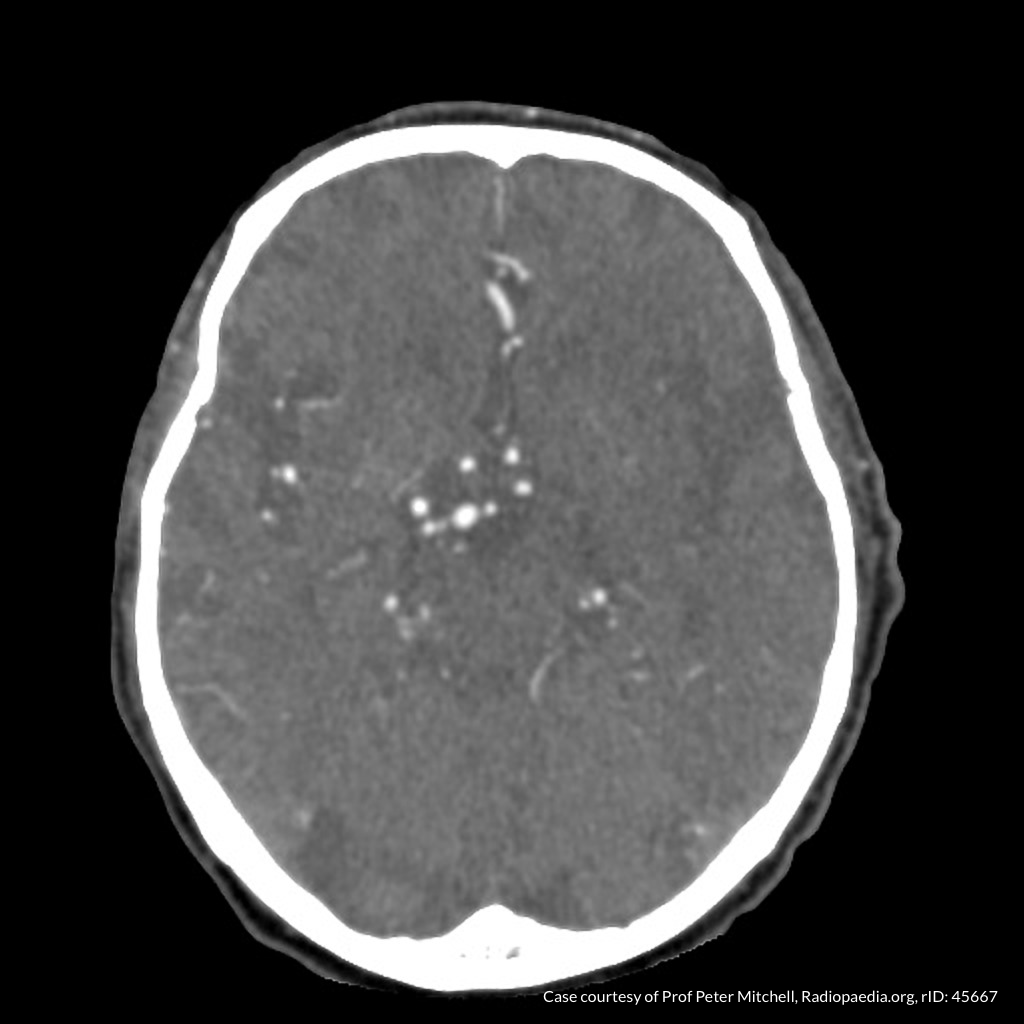

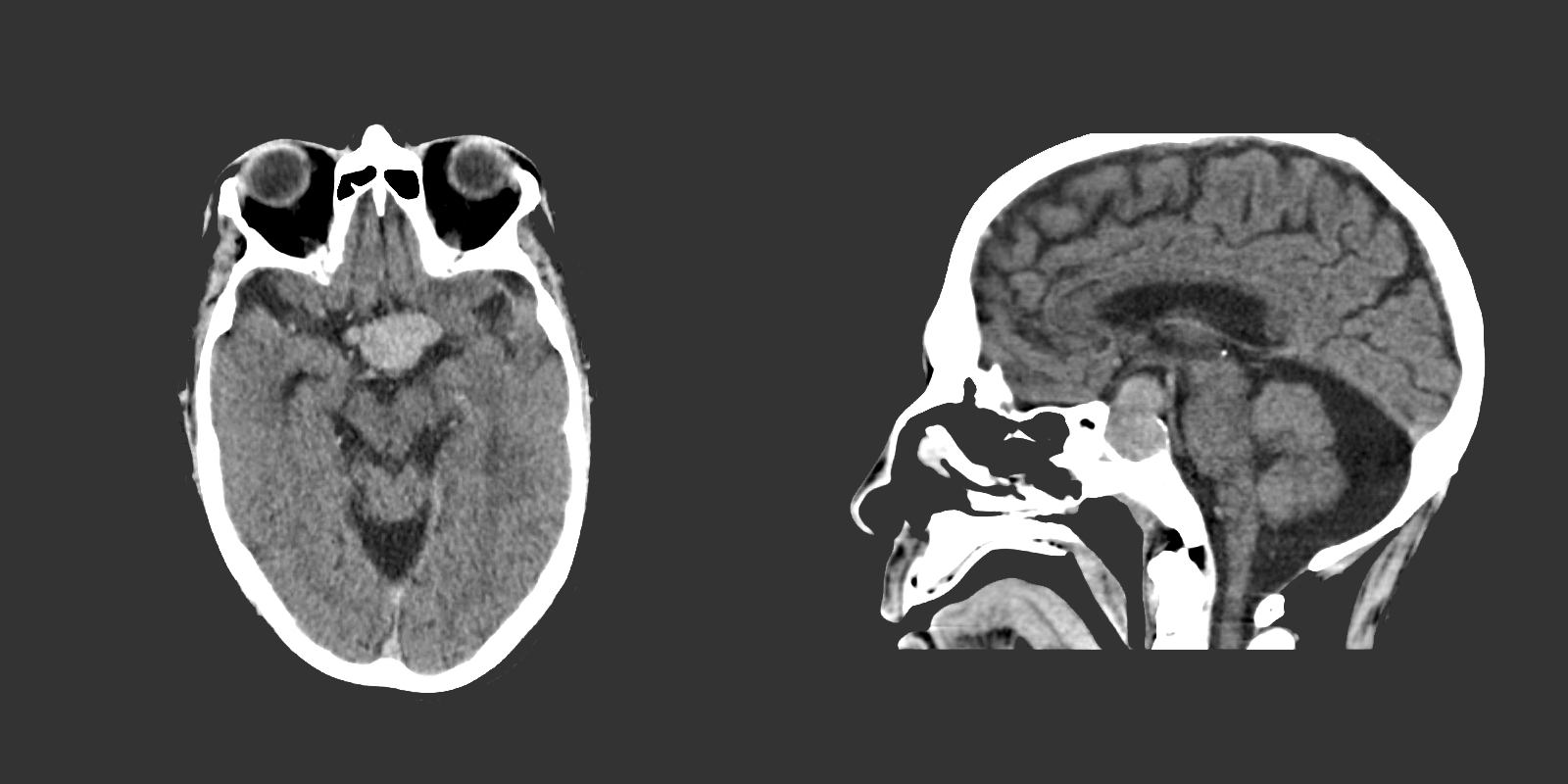

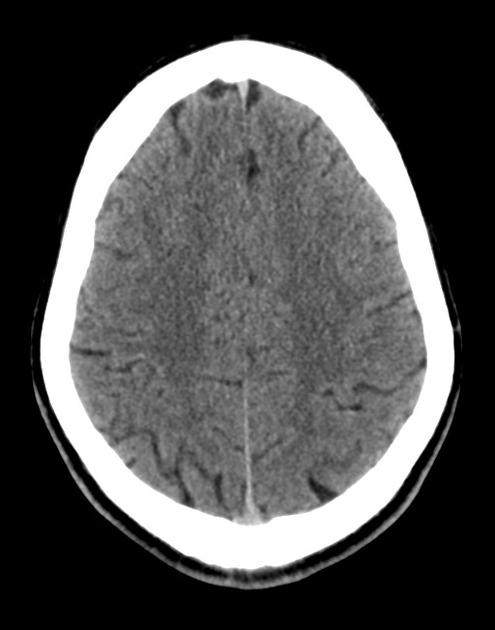

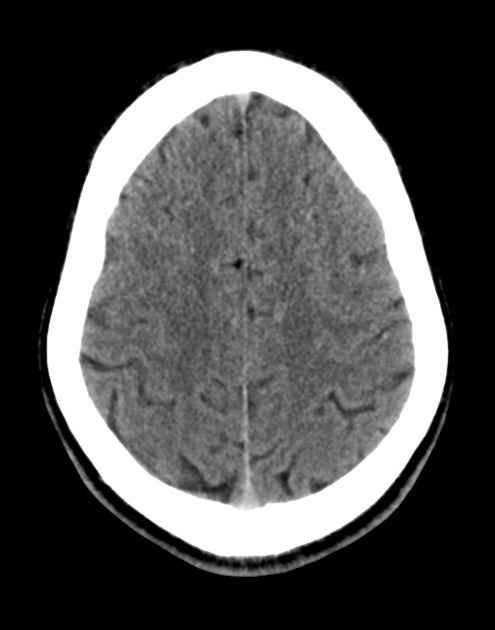

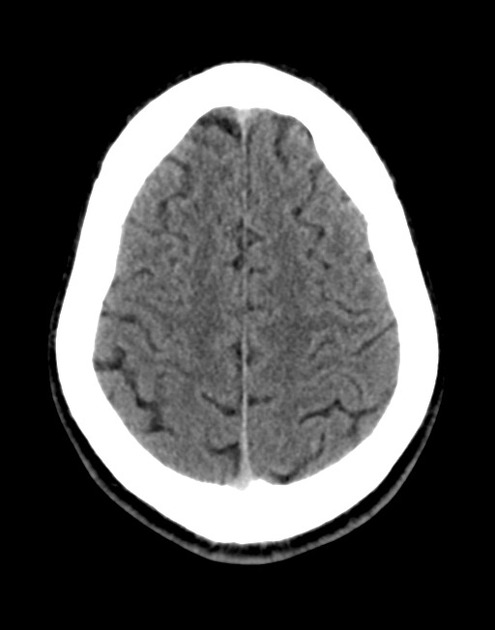

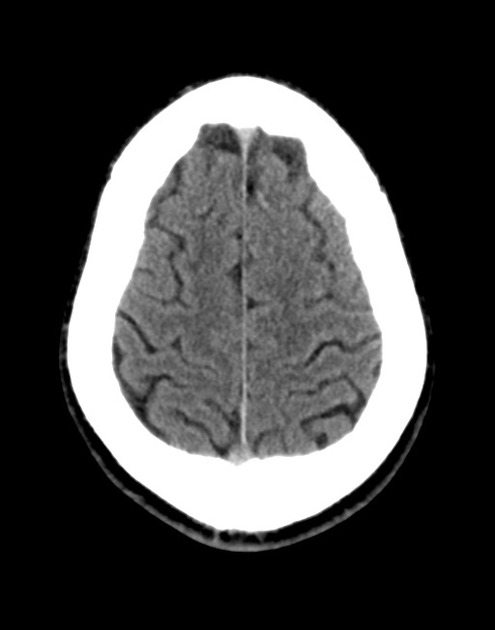

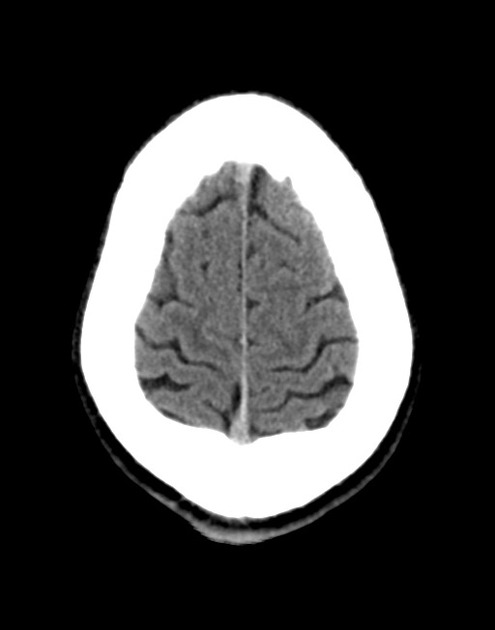

# Tremor: High-frequency, high-amplitude rest and action tremor suggestive of essential tremor or exaggerated physiological tremor associated with pain and emotional distress. No other neurological symptoms (HA, weakness) and non-focal neurological exam (aside from anesthesia localized around recent surgical incisions in LLE). Will continue monitoring, no need for imaging at this time.

# Gout: Patient with history of gout, however, doubt that current arthralgia associated with acute gouty flare. Will continue monitoring exam and consider ortho consultation for joint aspiration.

Differential Diagnosis of Monoarticular Arthralgia: 1,2

Differential Diagnosis of Polyarticular Arthralgia 1,3

Use of Serum Uric Acid in Acute Gout 4

In this patient, serum uric acid levels were checked. However, a normal serum urate (SU) does not exclude an acute gout flare. Studies have shown 12-43% of patients with acute gout flares have normal SU. An elevated SU (>8.0mg/dL) may support the diagnosis of a gout flare but is not itself diagnostic.

Approach to Joint Pain: 3

Certain key historical elements can help narrow the differential diagnosis.

- Inflammation:

- Definition: Presence of erythema, warmth, swelling, pain with passive ROM, morning stiffness suggests inflammatory cause (arthritis)

- Common causes: Infection, gout, RA, SLE

- Chronology:

- Definition: Acute <6wks, chronic > 6wks

- Distribution:

- Definition: Location (large/small), symmetry

- Common causes:

- OA: DIP + PIP, spares wrists, elbows, ankles

- RA: PIP + MCP

- Spondylarthropathies (large joints)

- Symmetric involvement: RA, SLE

- Asymmetric involvement: Psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, gout

- Course:

- Definition: Intermittent (gout), migrating (GC, Lyme, SLE)

- Demographics:

- Female <50: RA, SLE

- Male > 40: gout (♂ 20yr after puberty, ♀ 20yr after menopause)

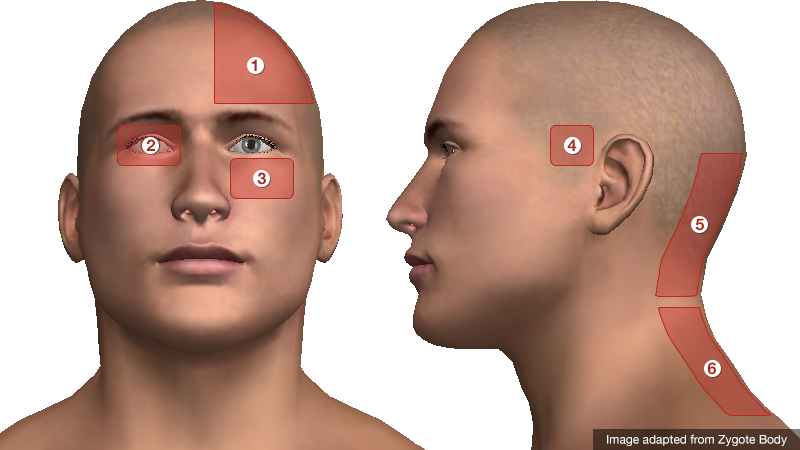

- Extra-articular manifestations:

- Malar rash, oral ulcers: SLE

- Proximal muscle weakness: polymyositis

- Psoriatic skin/nail lesions: psoriatic arthritis

- Oral ulcers, vesicopustules on palms/soles, recent diarrheal illness: reactive arthritis

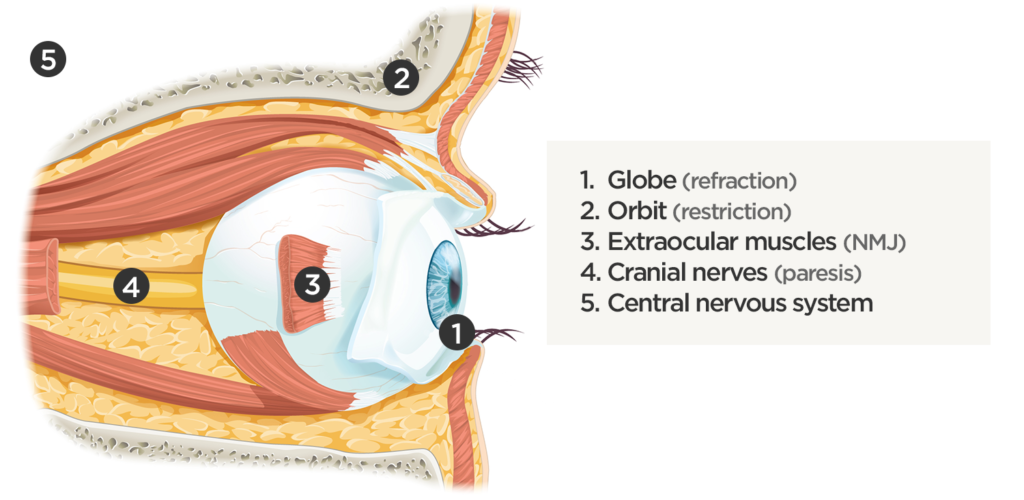

Differential Diagnosis of Tremor: 5,6

References:

- Cush JJ, Lipsky PE. Chapter 331. Approach to Articular and Musculoskeletal Disorders. In: Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012. http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=9139045. Accessed August 27, 2013.

- Siva, C., Velazquez, C., Mody, A., & Brasington, R. (2003). Diagnosing acute monoarthritis in adults: a practical approach for the family physician. American family physician, 68(1), 83–90.

- Mies Richie, A., & Francis, M. L. (2003). Diagnostic approach to polyarticular joint pain. American family physician, 68(6), 1151–1160.

- Schlesinger, N., Norquist, J. M., & Watson, D. J. (2009). Serum urate during acute gout. The Journal of rheumatology, 36(6), 1287–1289. doi:10.3899/jrheum.080938

- Hess, C. W., & Pullman, S. L. (2012). Tremor: clinical phenomenology and assessment techniques. Tremor and other hyperkinetic movements (New York, N.Y.).

- Crawford, P., & Zimmerman, E. E. (2011). Differentiation and diagnosis of tremor. American family physician, 83(6), 697–702.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)