CC:

Consult for acute kidney injury

HPI:

63M with a history of liver cirrhosis of cryptogenic etiology, portal vein thrombosis, and esophageal varices s/p banding (2011) who was admitted to an OSH for altered mental status and hypotension requiring dopamine and was transferred to this facility for a higher level of care.

The nephrology service was consulted for elevated serum creatinine concerning for AKI. The patient has a baseline creatinine of 1.1 (3/2013), 1.9 on transfer and continued worsening to peak of 2.6 today.

PMH:

- Asthma

- COPD

- Cirrhosis (PVT, encephalopathy)

- Inguinal hernia (recurrent)

|

PSH:

- Appendectomy

- Bilateral inguinal hernia repair

|

FH:

|

SHx:

|

Meds:

- albumin 25g i.v. q.6.h.

- erythromycin 1,000mg p.o. q.1.h.

- fluticasone-salmeterol 1 puff b.i.d.

- lactulose 45g p.o. q.6.h.

- neomycin 1,000mg p.o. q.1.h.

- pantoprazole 40mg i.v. daily

- rifaximin 550mg p.o. b.i.d.

- sodium benzoate 5g p.o. b.i.d.

|

Allergies:

|

Physical Exam:

| VS: |

T |

37.4 |

HR |

90 |

RR |

15 |

BP |

86/48 |

O2 |

97% RA |

| Gen: |

Chronically ill-appearing. |

| HEENT: |

PERRL, scleral icterus, MMM |

| CV: |

RRR |

| Lungs: |

CTAB |

| Abd: |

+BS, soft, non-tender, non-distended |

| GU: |

Large ascites filled scrotum, testicles/inguinal canal not easily palpated |

| Ext: |

Warm, well-perfused |

| Skin: |

No palmar erythema, no vascular spiders |

| Neuro: |

AAOx4, CN II-XII grossly intact |

Labs:

- BMP: 134/4.5/103/20/41/3.0/106 (Ca 9.3, Mg 3.7, PO4 2.4)

- LFT: AST 89, ALT 33, TB 26.6, CB 16.1, Alb 2.7

- NH4 167

Imaging:

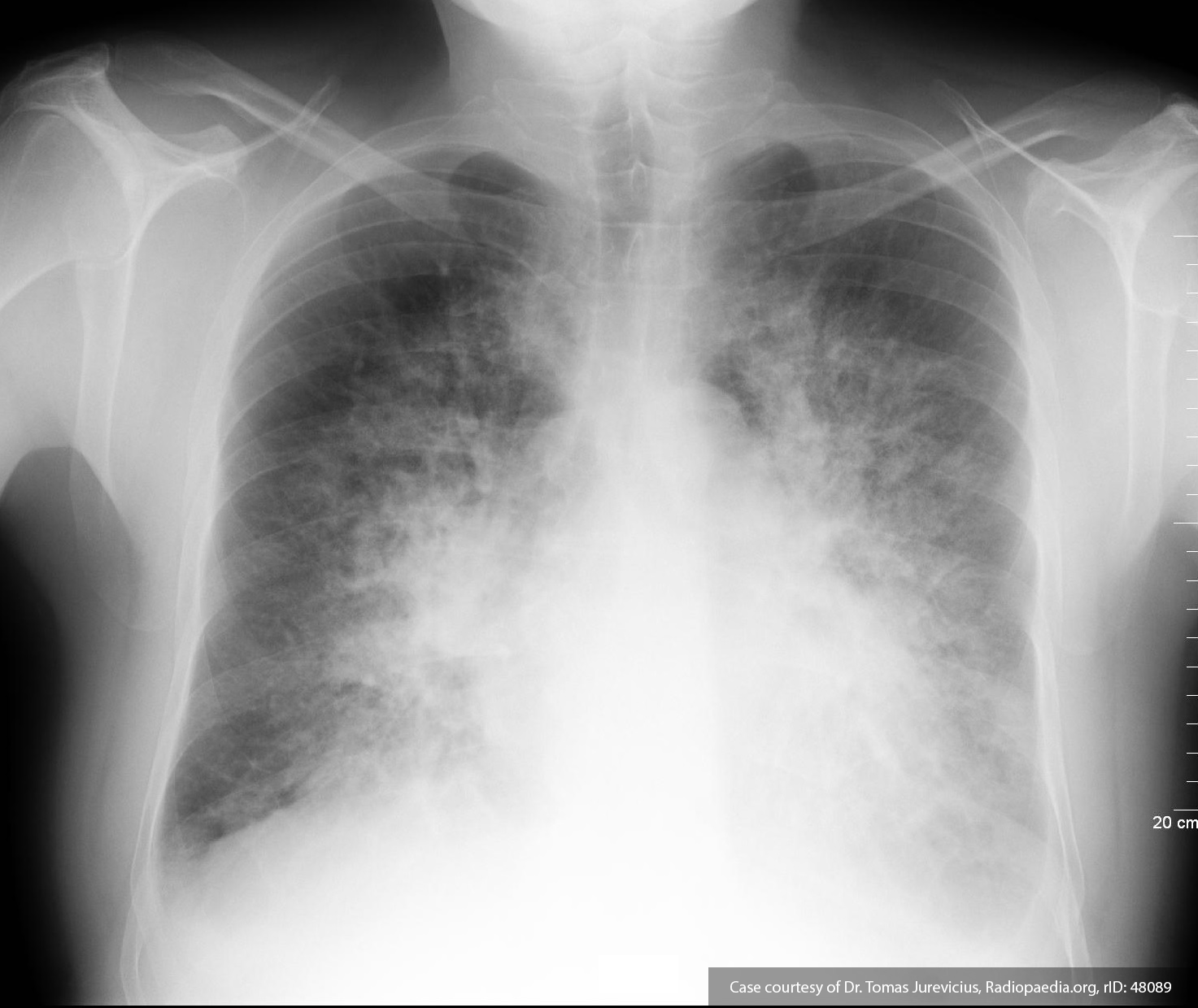

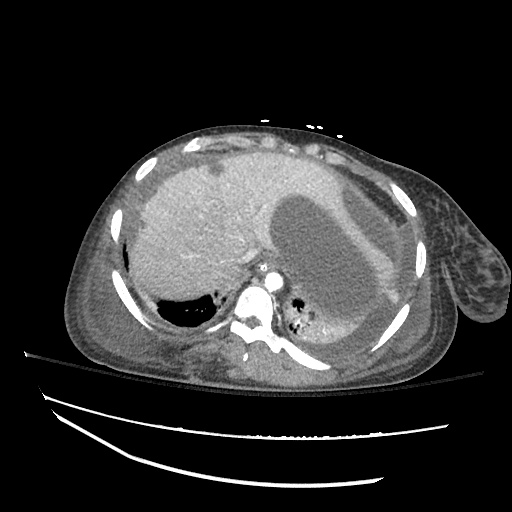

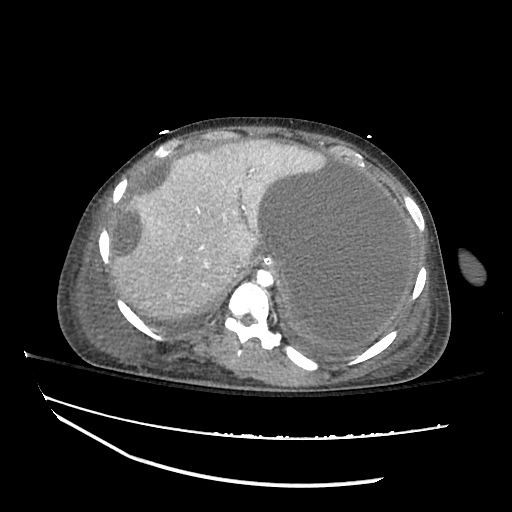

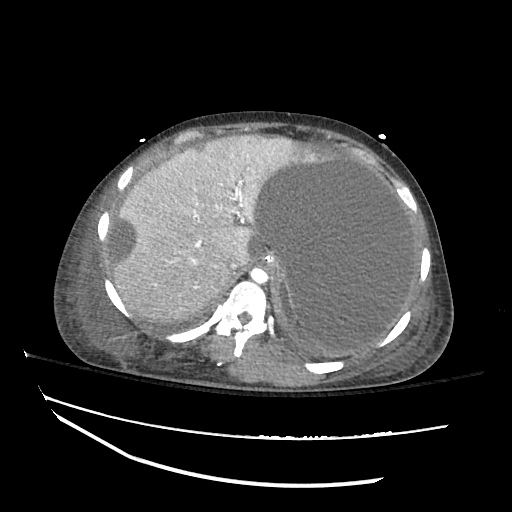

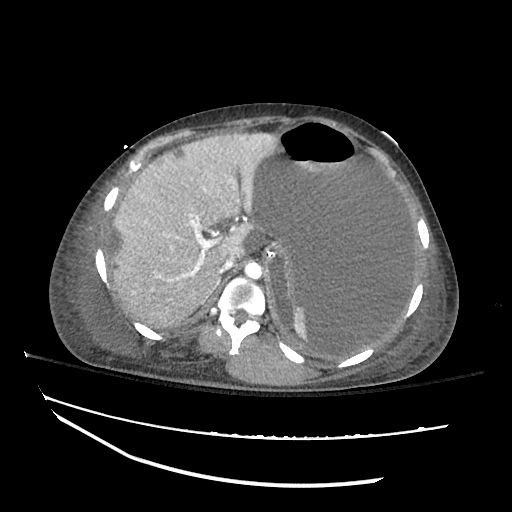

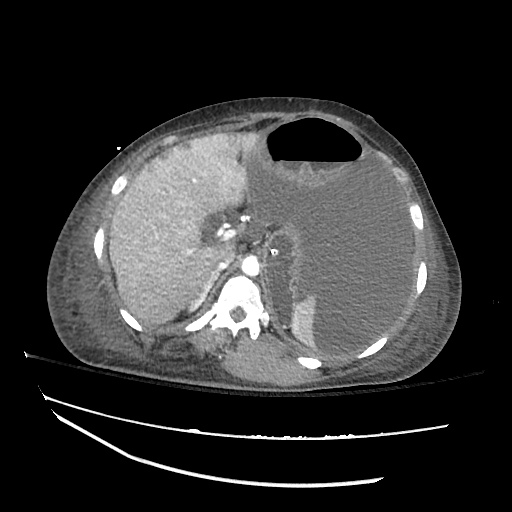

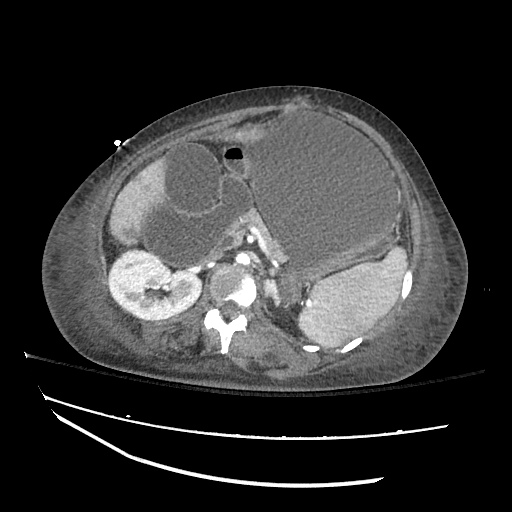

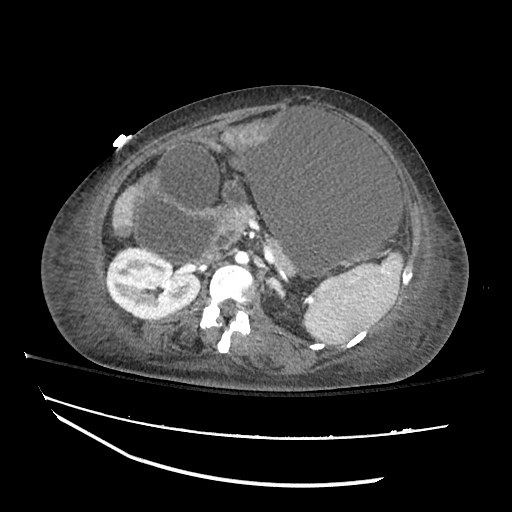

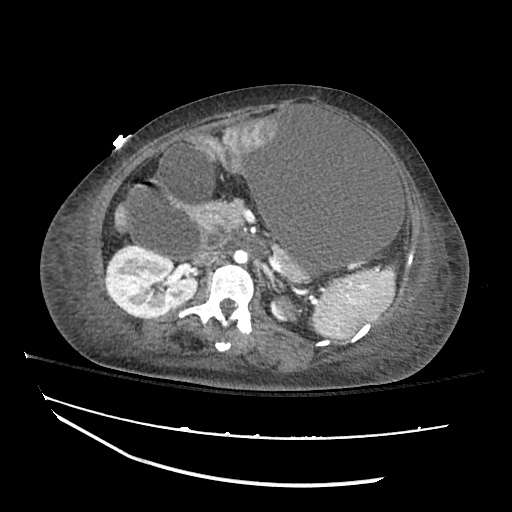

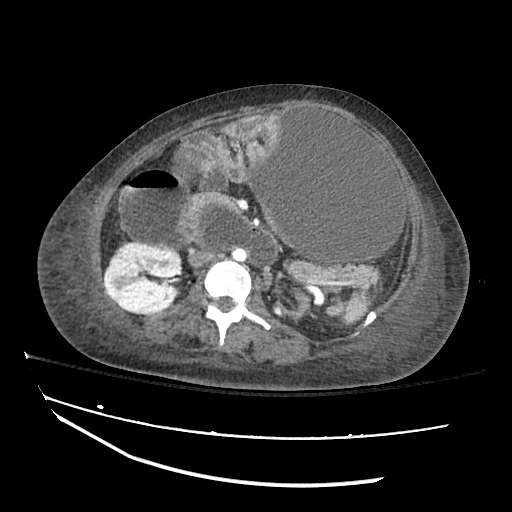

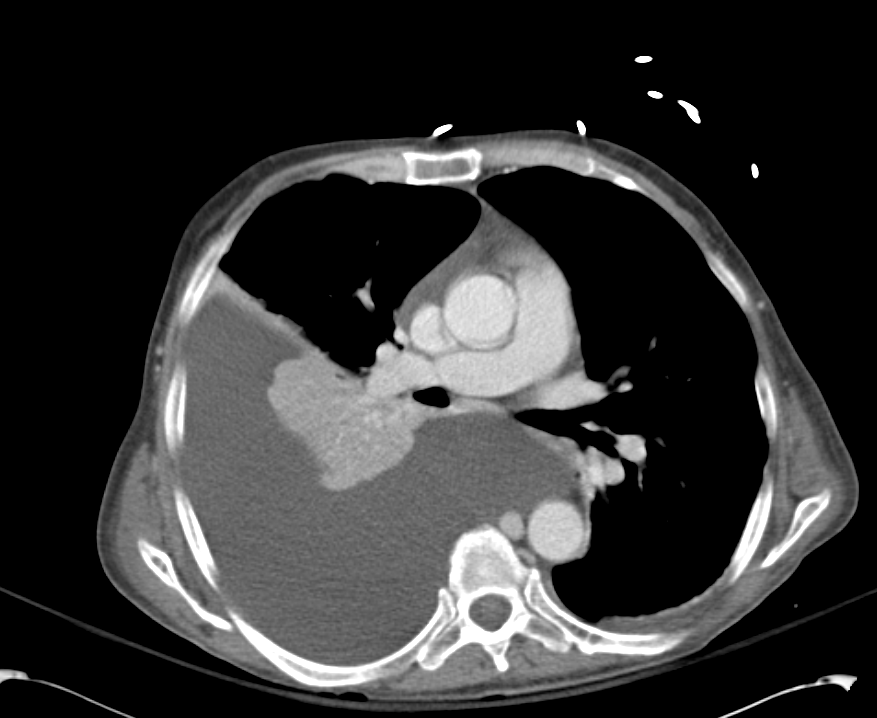

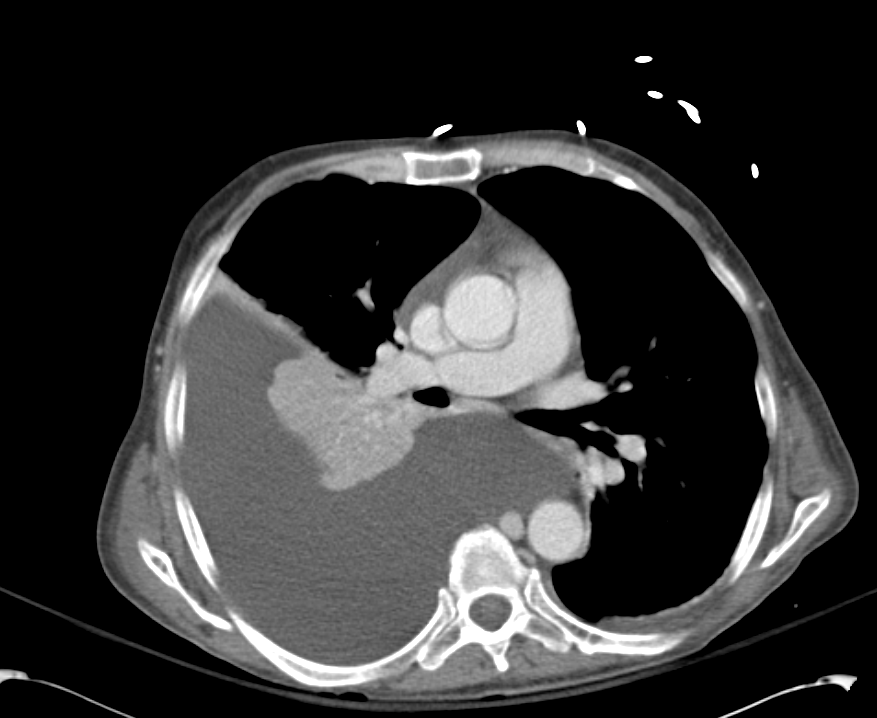

Pleural Effusion

Large right pleural effusion with underlying compressive atelectasis.

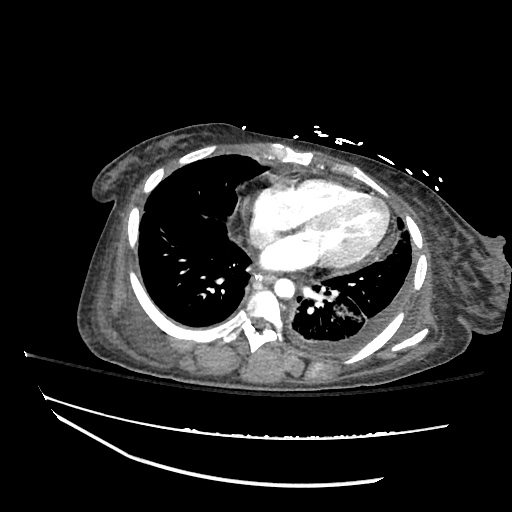

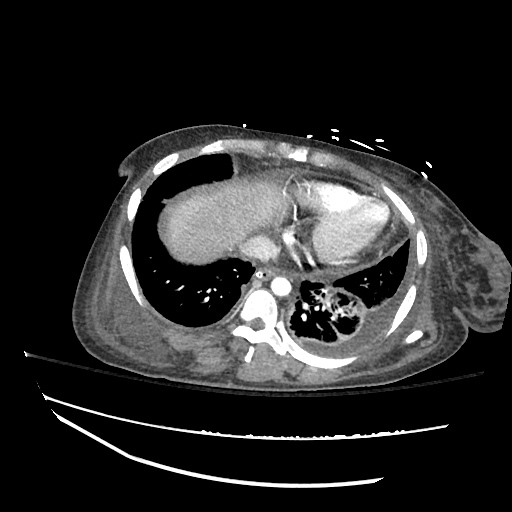

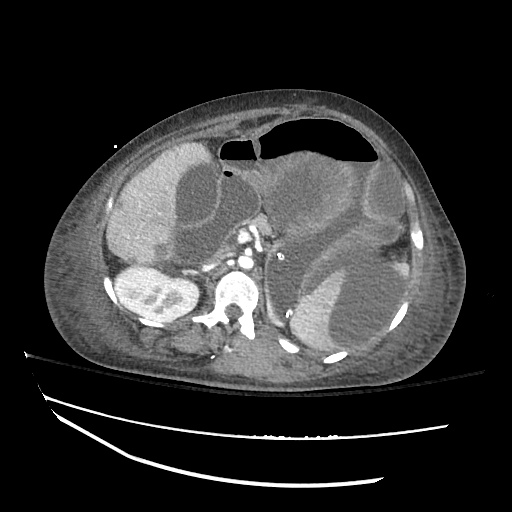

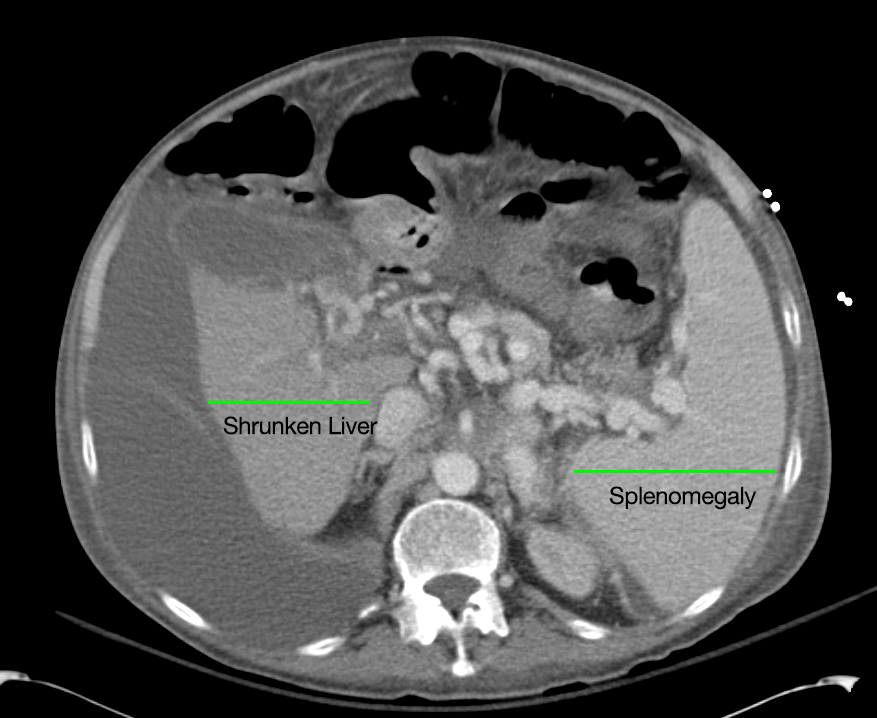

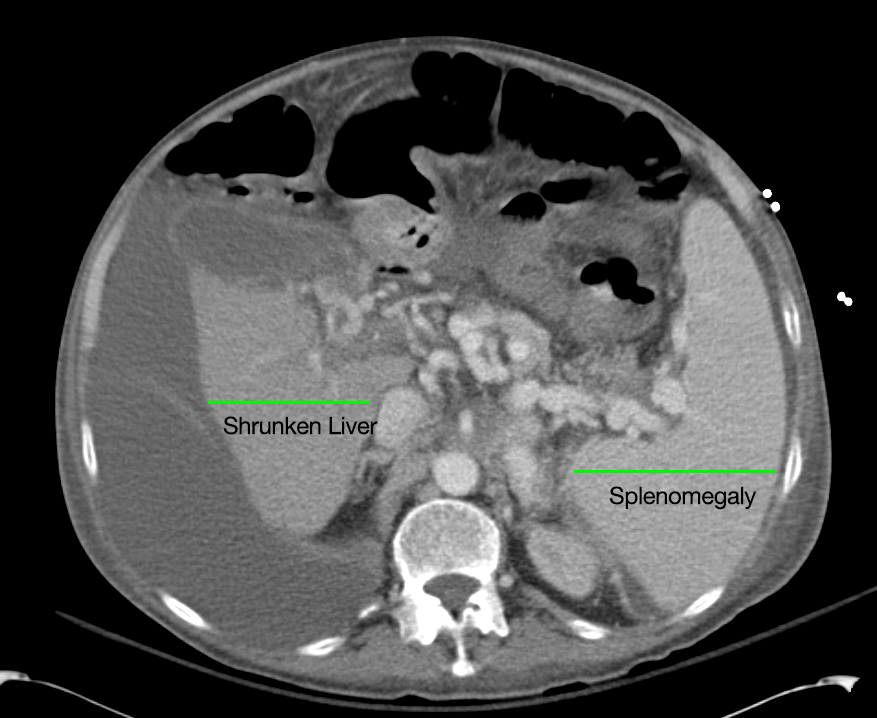

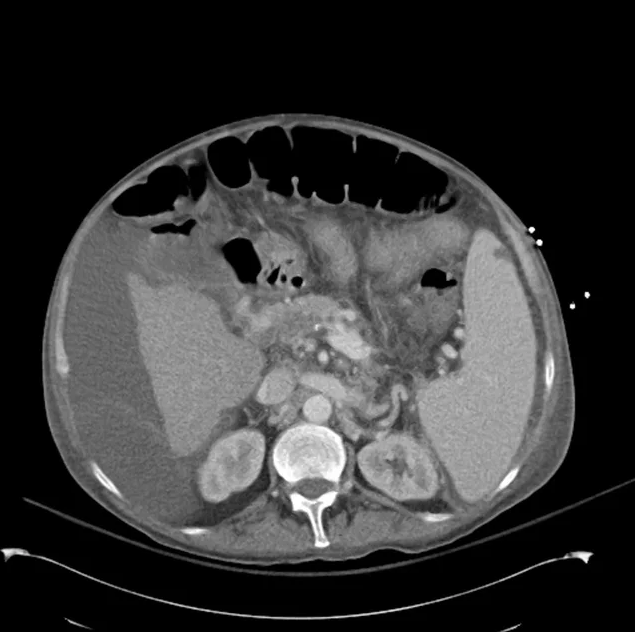

Cirrhosis and Portal Hypertension

Shrunken/nodular liver with sequelae of portal hypertension including perisplenic collaterals, and splenomegaly.

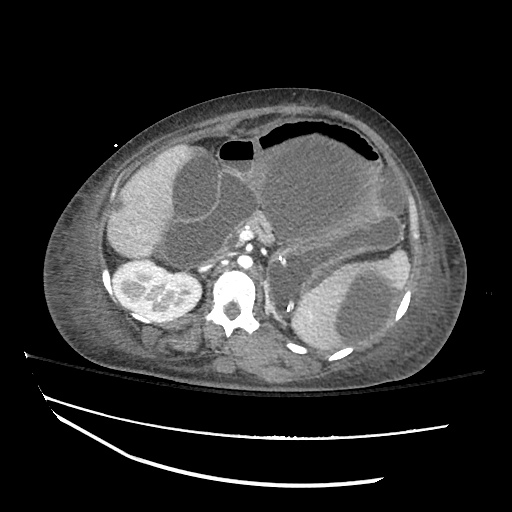

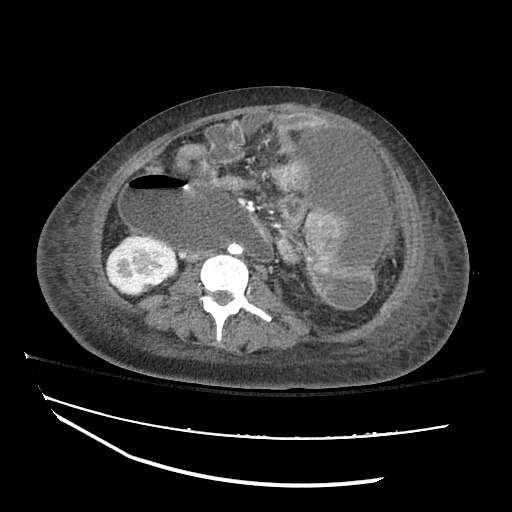

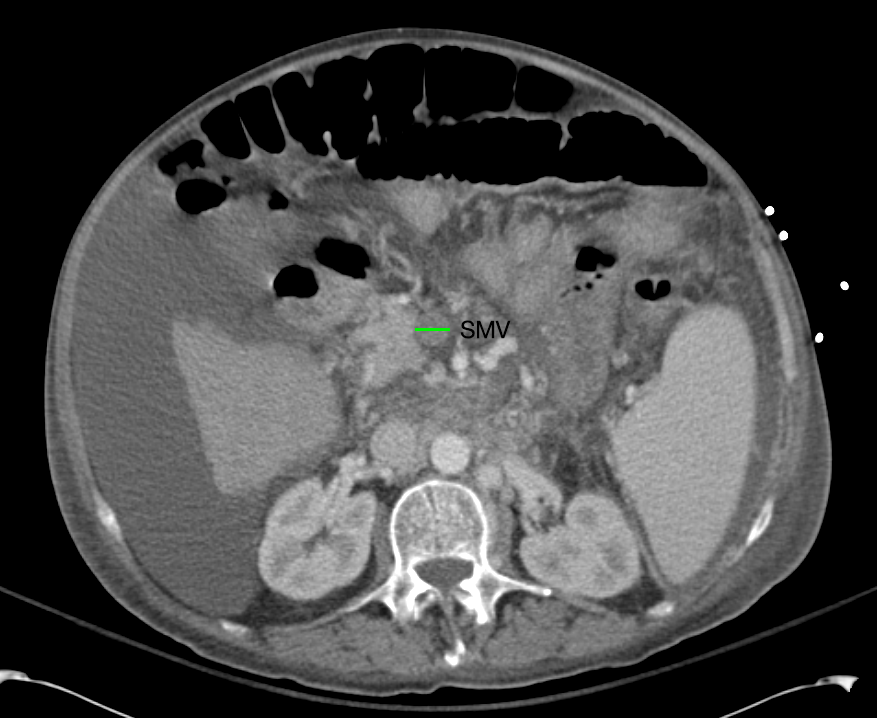

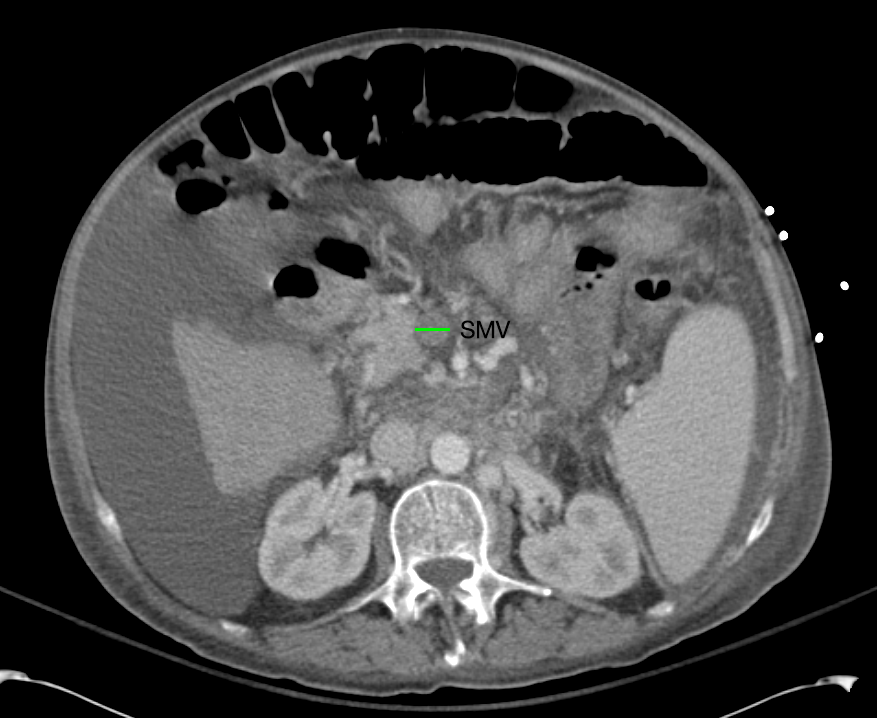

SMV Thrombosis

Near-total thrombosis of the portal vein extending down to superior mesenteric vein.

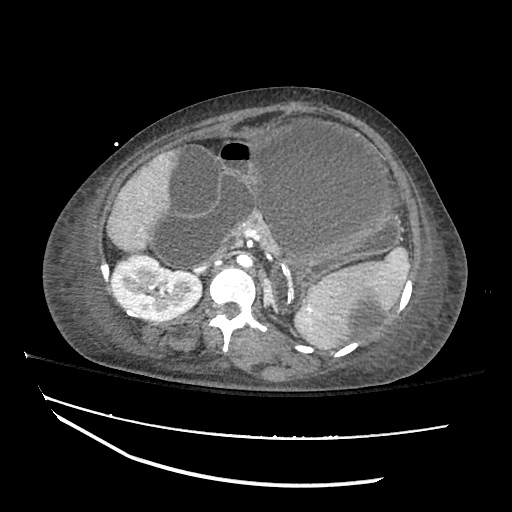

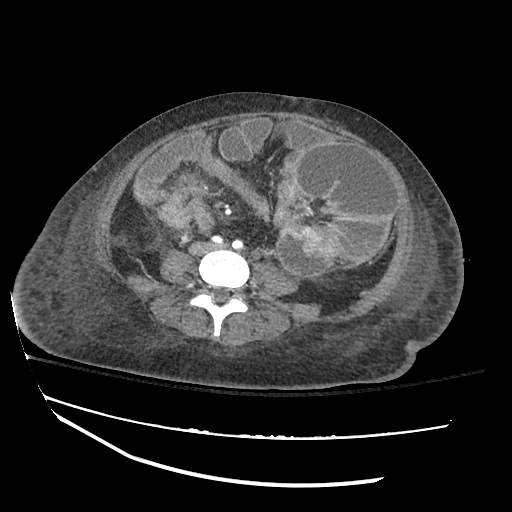

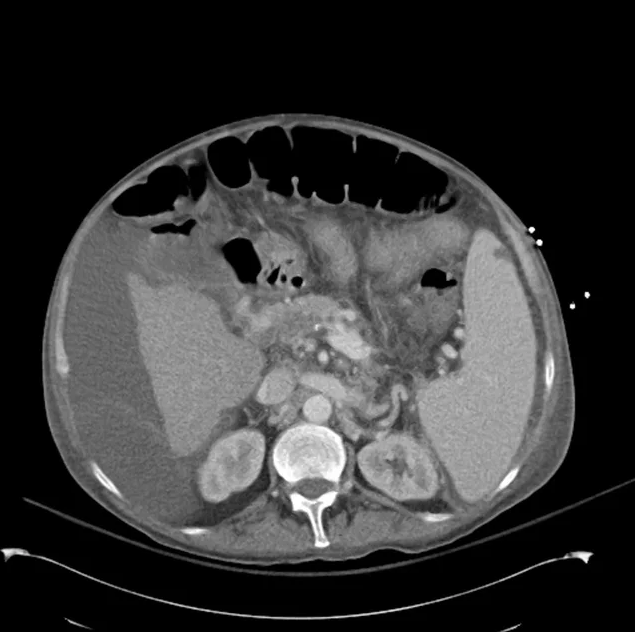

B/L Inguinal Hernias

Large volume abdominal ascites with a large amount of fluid extending into the bilateral inguinal canals.

Large Right Inguinal Hernia

Large volume abdominal ascites with a large amount of fluid extending into the bilateral inguinal canals.

CT Abdomen/Pelvis (PVT)

Assessment/Plan:

63M with a history of liver cirrhosis of cryptogenic etiology, recently with hypotension prior to transfer to this facility and increase in creatinine from 1.9-3.0 on current admission (from baseline 1.1).

These findings indicate acute kidney injury, likely hepatorenal syndrome vs. acute tubular necrosis 2/2 prolonged hypotension. Plan to discontinue diuretics and start albumin challenge (1g/kg/day divided q6h x2d). Will also check UA, urine Na/cr/urea/eos, renal US (evaluate obstruction, kidney size). Start midodrine/octreotide for underlying HRS.

- Neuro: Intermittent confusion. Lactulose, rifaximin, benzoate.

- Resp: 2L NC. ABG 7.36/51/87/27.7/+2. CXR: Large R effusion.

- CV: Levo 0.075. Midodrine 15 TID. MAPs 60, HR 80s.

- GI: NPO/NGT. TPN.

- Renal: See above.

- Heme: Coagulopathy, keep INR <2.5

- ID: Afebrile. No abx.

- Endo: Euglycemic

Renal Failure in Cirrhosis:

Renal failure in cirrhosis is associated with higher mortality both before and after transplant. The main causes of renal failure in cirrhosis are detailed below, with particular attention to an entity unique to cirrhosis: the hepatorenal syndrome.1

| Disorder |

Pathogenesis |

Diagnosis |

Management |

| HRS |

Dilation of splanchnic arteries initially compensated by increased CO eventually decompensates with activation of mechanisms to preserve ECBV (RAAS, SNS, ADH) leading to fluid retention (ascites, edema) and renal failure due to intrarenal vasoconstriction.Bacterial translocation and the resulting inflammatory response may contribute to splanchnic vasodilation (through production of vasoactive factors like NO). |

- Serum creatinine > 1.5mg/dl- Not reduced with 1g/kg albumin

- No confounding factors (2d off diuretics, no nephrotoxic agents, no shock, no e/o intrinsic renal disease)

- Type 1: doubling creatinine > 2.5mg/dL in <2wk

- Type 2: stable, slower progression

|

- Vasoconstrictor therapy- Albumin

- Portasystemic shunting

- Renal replacement therapy

- Prevention

|

| Intrinsic renal |

Some causes of liver disease are also associated with intrinsic renal pathology (ex. GN associated with HBV, HCV). |

- Proteinuria, hematuria

- Renal bx

- Active urinary sediment

|

- Antiviral therapy if appropriate

|

| Pre-renal AKI |

Hemorrhage (GIB), fluid losses (excess diuresis, diarrhea from lactulose). |

- Suspected from patient history

- Low FENa, bland urine sediment

|

- Hemorrhage: replace volume with fluids, blood products. Control bleeding.

- Discontinue diuretics, administer fluids if tolerated

|

| ATN |

Severe ischemic or toxic (NSAID’s, nephrotoxic medications) |

- Renal tubular epithelial cells favor ATN (granular casts common in ATN, HRS)

|

- Withdraw therapy

- Avoid nephrotoxic agents

|

Pathophysiology of Hepatorenal Syndrome:

Evaluation:

The evaluation of suspected renal failure in patients with cirrhosis involves assessment of renal function for evidence of acute impairment, as well as analaysis of urine for protein or active sediment to suggest intrinsic renal disease (possibly warranting renal ultrasonography or biopsy). Additionally, patients should be evaluated for evidence of bacterial infection including assessment of ascites if present as SBP produces a more severe form of the inflammatory vasodilation mechanism suspected to play a role in HRS.

Treatment:

For renal failure not caused by the hepatorenal syndrome, identification and management of the underlying cause is critical (intrinsic renal disease, hypovolemia/hemorrhage, nephrotoxicity, infection). For suspected HRS, management is dependent on the acuity and setting. In the intensive care unit, vasoconstrictor therapy (norepinephrine, vasopressin) in association with albumin is effective in the treatment of HRS.2,3 In less acute settings, a combination of midodrine, octreotide and albumin improves renal function and is associated with lower short-term mortality.4 Alternatives for patients who do not respond to medical therapy include TIPS, dialysis and transplant.

Summary:

Renal failure in ESLD is due to the causes, complications or management of cirrhosis and has important implications, with HRS in particular offering the worst prognosis.5 Early recognition and management is critical to improving outcomes.

References:

- Ginès, P., & Schrier, R. W. (2009). Renal failure in cirrhosis. The New England journal of medicine, 361(13), 1279–1290. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0809139

- Singh, V., Ghosh, S., Singh, B., Kumar, P., Sharma, N., Bhalla, A., Sharma, A. K., et al. (2012). Noradrenaline vs. terlipressin in the treatment of hepatorenal syndrome: a randomized study. Journal of hepatology, 56(6), 1293–1298. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2012.01.012

- Kiser, T. H., Fish, D. N., Obritsch, M. D., Jung, R., MacLaren, R., & Parikh, C. R. (2005). Vasopressin, not octreotide, may be beneficial in the treatment of hepatorenal syndrome: a retrospective study. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation, 20(9), 1813–1820. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfh930

- Esrailian, E., Pantangco, E. R., Kyulo, N. L., Hu, K.-Q., & Runyon, B. A. (2007). Octreotide/Midodrine therapy significantly improves renal function and 30-day survival in patients with type 1 hepatorenal syndrome. Digestive diseases and sciences, 52(3), 742–748. doi:10.1007/s10620-006-9312-0

- Alessandria, C., Ozdogan, O., Guevara, M., Restuccia, T., Jiménez, W., Arroyo, V., Rodés, J., et al. (2005). MELD score and clinical type predict prognosis in hepatorenal syndrome: relevance to liver transplantation. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), 41(6), 1282–1289. doi:10.1002/hep.20687