HPI:

64F with a history of CAD, MI, CHF, CLL and rheumatoid arthritis who presented to the emergency department after transfer from a rehabilitation facility for respiratory distress. The patient reported several days of progressive shortness of breath with dyspnea on exertion. She also noted some associated orthopnea and lower extremity edema. The patient was recently hospitalized for similar symptoms and was diagnosed with CHF at the time. At the rehab facility, the patient became hypoxemic and hypertensive, reporting shortness of breath and chest pain prior to presentation.

Hospital Course:

The patient was initially managed with BiPAP and nitroglycerin continuous infusion, but was then stable on supplemental O2 via nasal cannula and was transitioned to long-acting nitrates and anti-hypertensives. The patient’s hypoxemic respiratory failure was initially attributed to acute exacerbation of left-ventricular heart failure, and the patient was managed with spot diuresis. However, there was no symptomatic improvement and the patient became hypernatremic so diuresis was held as alternative diagnoses were explored.

A transthoracic echocardiogram showed preserved LVEF (50-55%), but some diastolic dysfunction and elevated PAP/RAP. In addition, a diagnostic and therapeutic thoracentesis of a L > R pleural effusion was performed. Pleural fluid studies were suggestive of a transudative process, though with some abnormal characteristics (including lymphocyte predominance, as well as presence of signet cells).

Rheumatology and pulmonology services were consulted for input and recommendations for further evaluation were appreciated. Per rheumatology, the patient’s diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis may not be consistent with her presentation or prior serologic studies. Her pleural fluid analysis was also not consistent with rheumatoid disease. According to pulmonary consult, the patient’s hypoxemia remains most consistent with left ventricular dysfunction though primary pulmonary processes cannot be excluded (and would warrant further evaluation with imaging and pulmonary function testing).

PMH:

- CHF

- CAD

- CVA

- Myocardial Infarction

- HTN

- Hypothyroidism

- CLL

- Anemia

FH:

- No family history of autoimmune disease.

- Mother: DM

SHx:

- Denies tobacco/EtOH/drug use

- Lives at home, at SNF since discharge

Meds:

- Furosemide 20mg p.o. daily

- Gabapentin 300mg p.o. t.i.d.

- Hydralazine 50mg p.o. t.i.d.

- Hydrochlorothiazide 25mg p.o. b.i.d.

- Hydroxychloroquine 200mg p.o. daily

- Levothyroxine 25mcg p.o. daily

- Minoxidil 2.5mg p.o. b.i.d.

- Pantoprazole 40mg p.o. daily

- Prednisone 15mg p.o. daily

Allergies:

Shellfish Physical Exam:

| VS: |

T |

37.2 |

HR |

84 |

RR |

15 |

BP |

147/75 |

O2 |

97% 4LNC |

| Gen: |

Elderly female, alert and oriented to self and place, responding appropriately to questions. |

| HEENT: |

Mucous membranes moist, sclera anicteric, no cervical lymphadenopathy. |

| CV: |

Regular rate and rhythm, normal S1/S2, no additional heart sounds. III/VI mid-systolic murmur heard best at LLSB with diastolic component, no radiation appreciated. Non-displaced PMI. JVP measured to 14cm. |

| Lungs: |

Decreased breath sounds in left lung field to inferior 2/3 with crackles above, on right crackles to inferior 1/2 of lung fields posteriorly. Dullness to percussion of inferior left lung field posteriorly. |

| Abdomen: |

Soft, non-tender, non-distended, no hepatosplenomegaly, no appreciable fluid wave. |

Ext: |

Bilateral lower extremities with 2+ pitting edema to knees, some hyperpigmentation to right lower extremity. |

Labs/Studies:

- CBC: 11.2/10.2/32.7/179

- BMP: 141/3.9/103/30/15/0.85/107

- INR: 0.9

- BNP: 1857

- UA: WBC 4, RBC 29 , +Bacteria, UCr 90, UPr 14

- Rheum: CCP <16, ANCA neg, RF 936

- Pleural Fluid: LDH 98 (serum 237), Protein 2.8 (serum 6.0), Glucose 107

- Cytology: Reactive mesothelial cells, histiocytes, lymphocytes, signet cells

Imaging

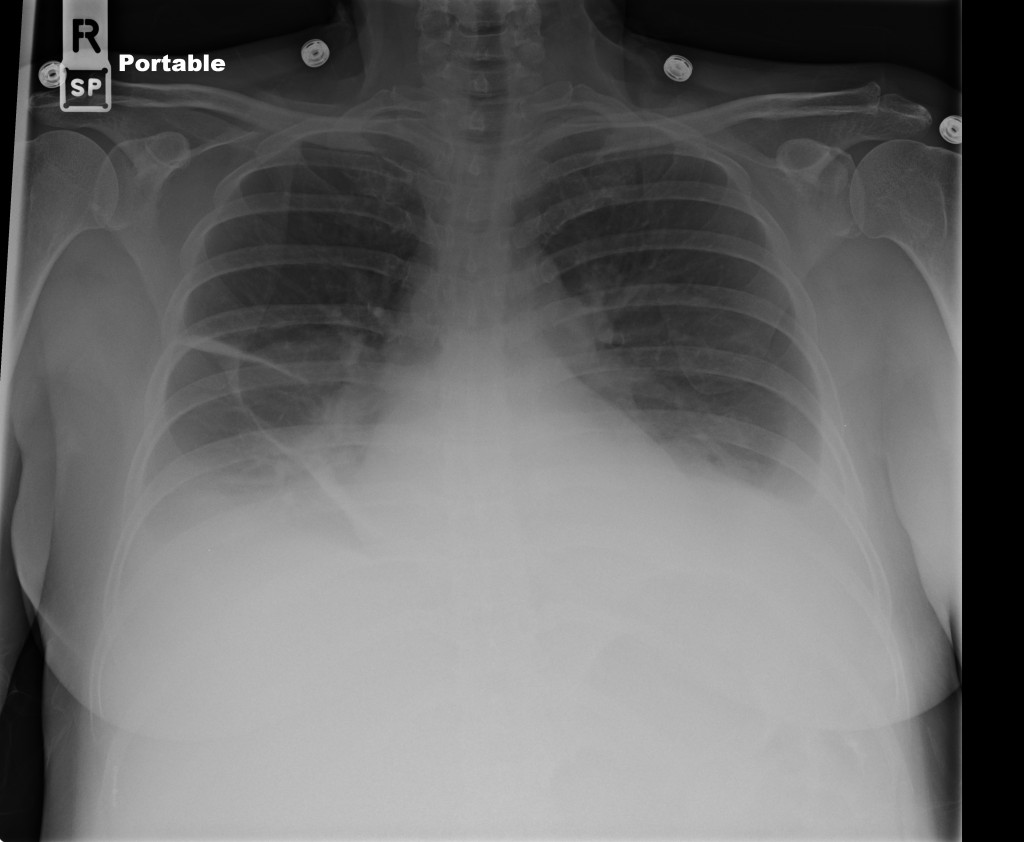

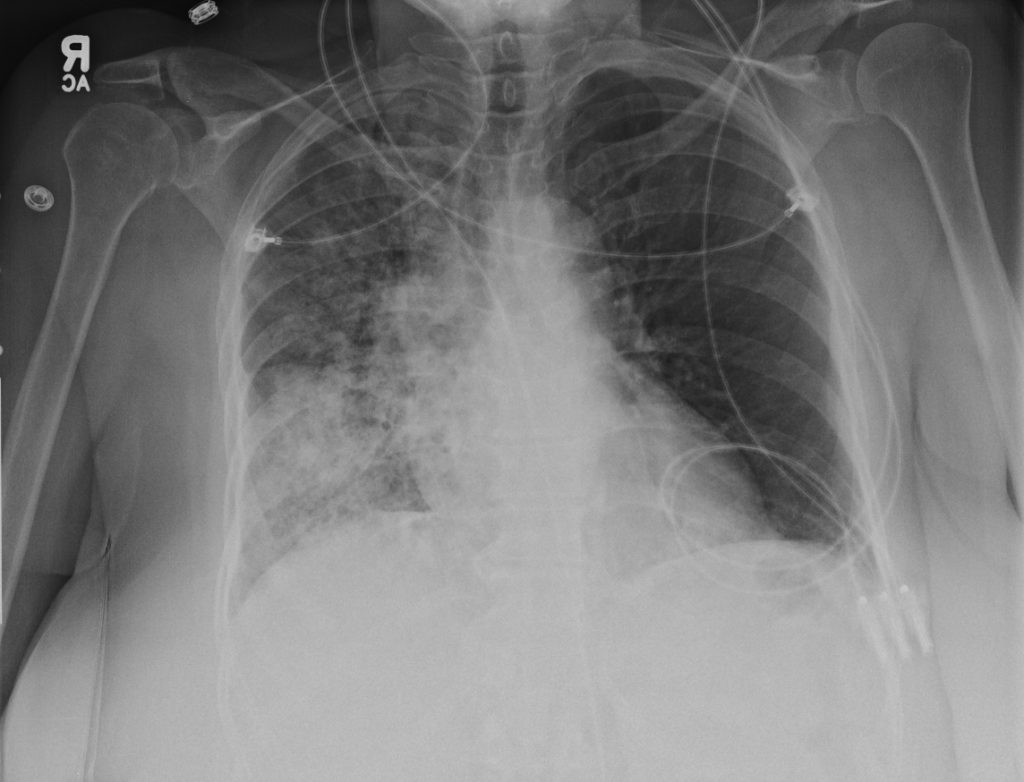

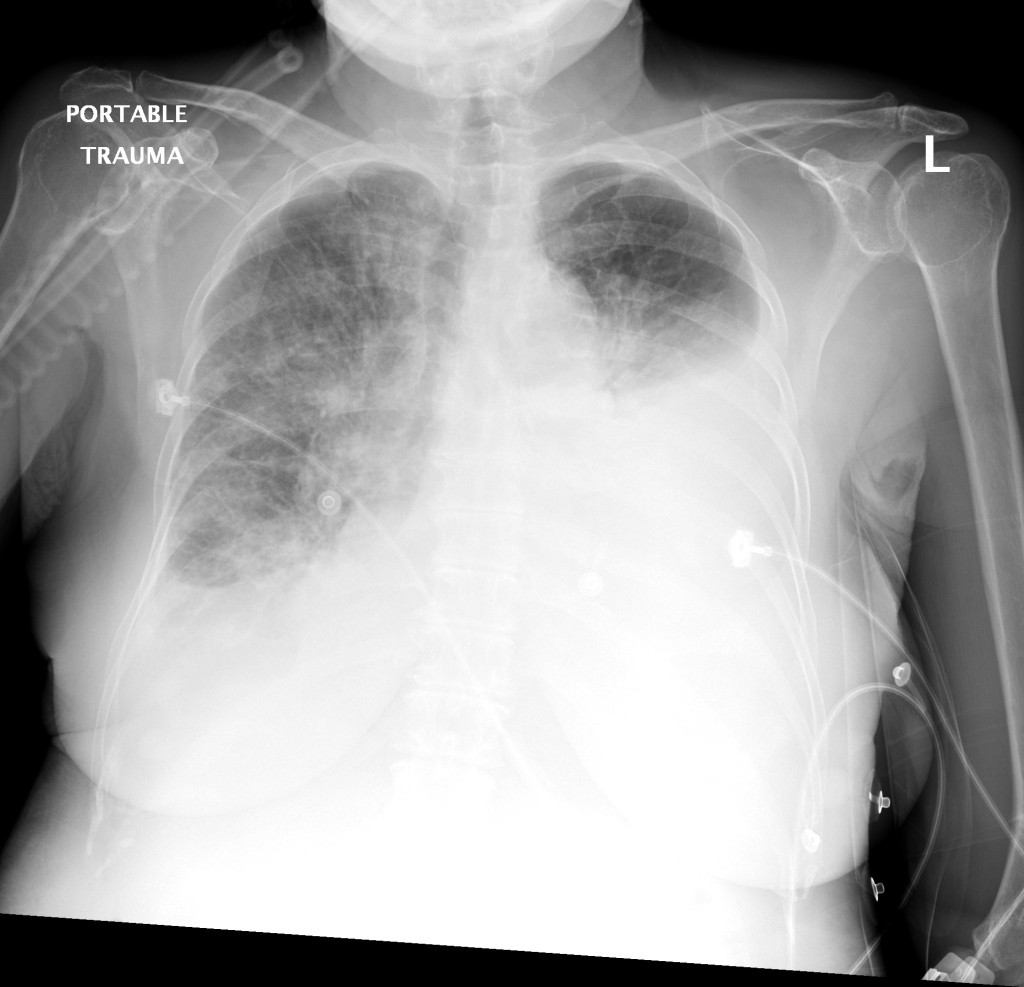

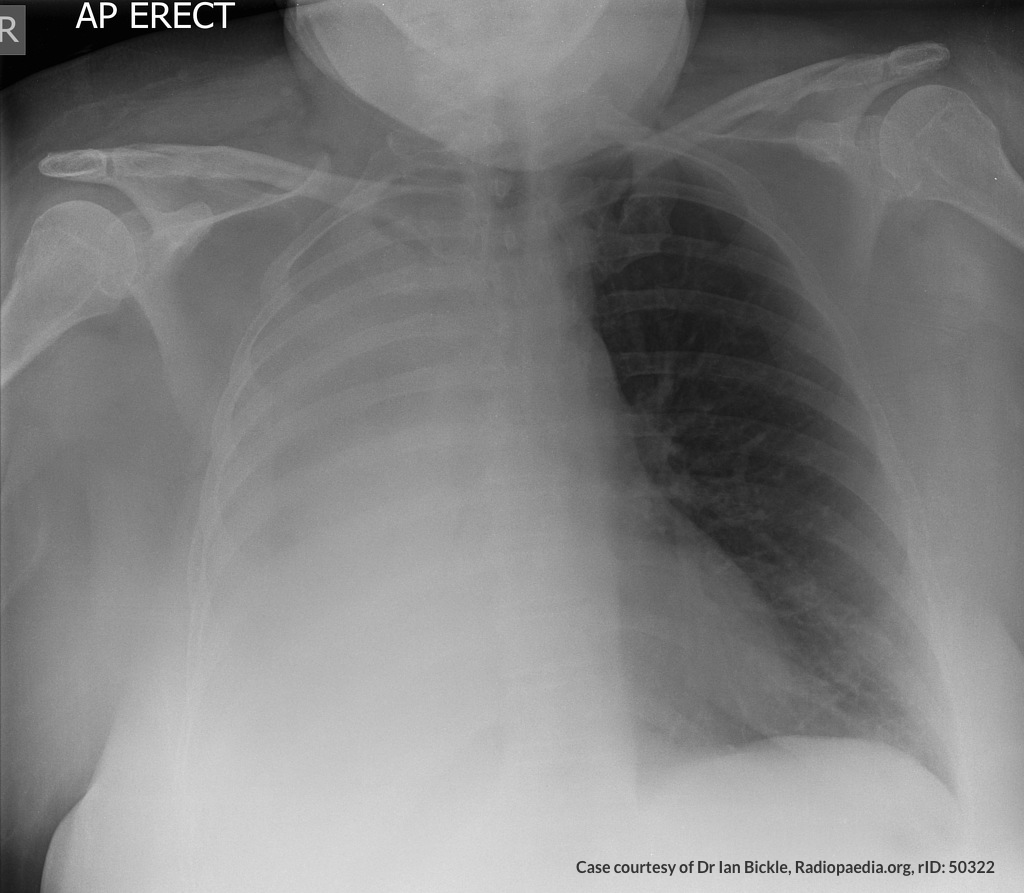

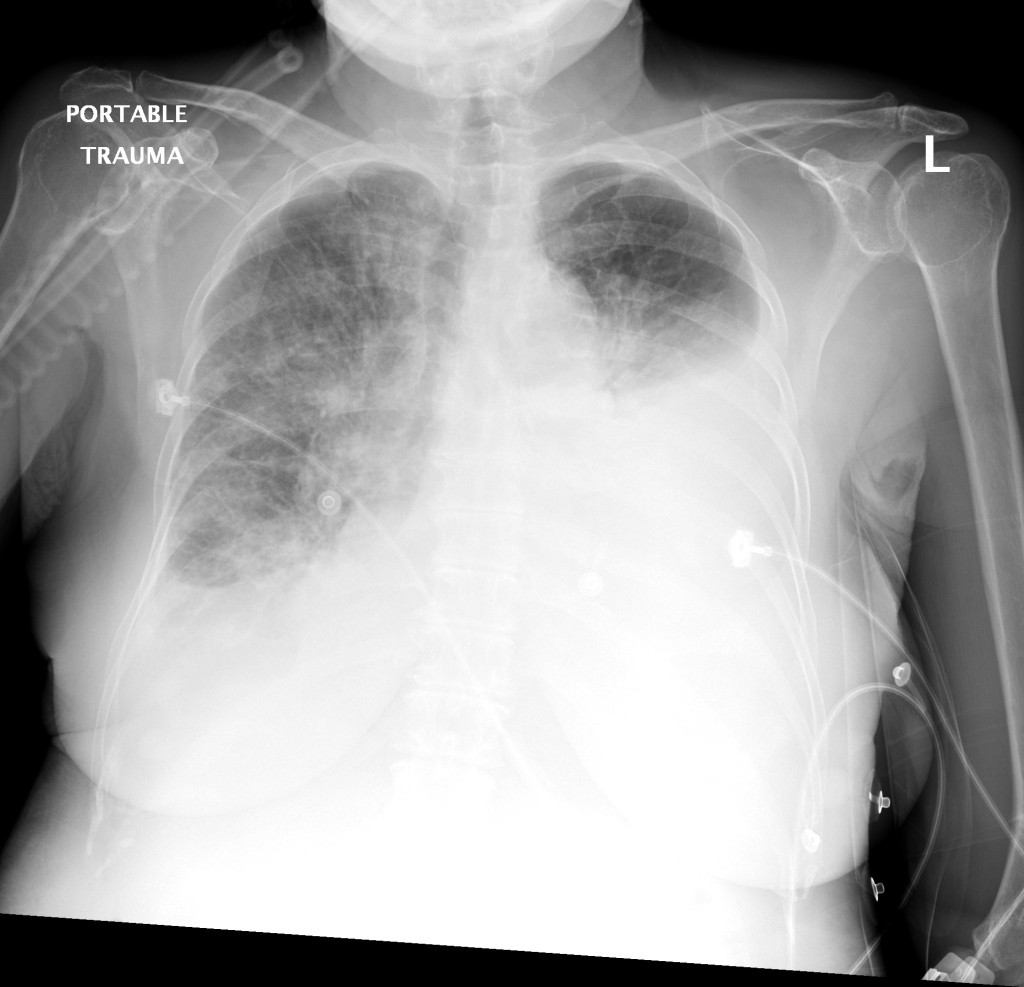

CXR

There is a large left pleural effusion obscuring the lower half of the left hemi thorax. The cardiac silhouette is also obscured. There is pulmonary venous vascular congestion. There is also a right pleural effusion with fluid tracking into the minor fissure. Pulmonary interstitial edema is also noted.

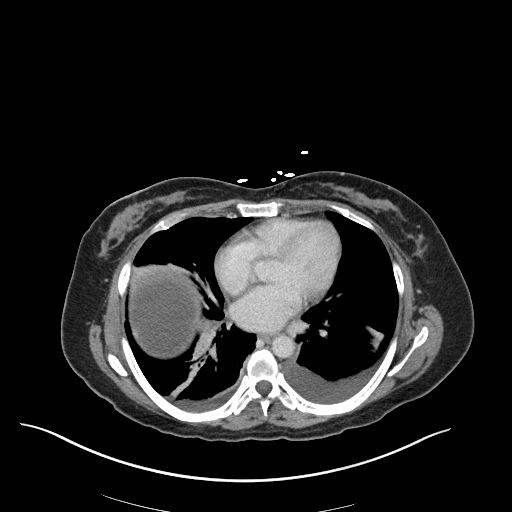

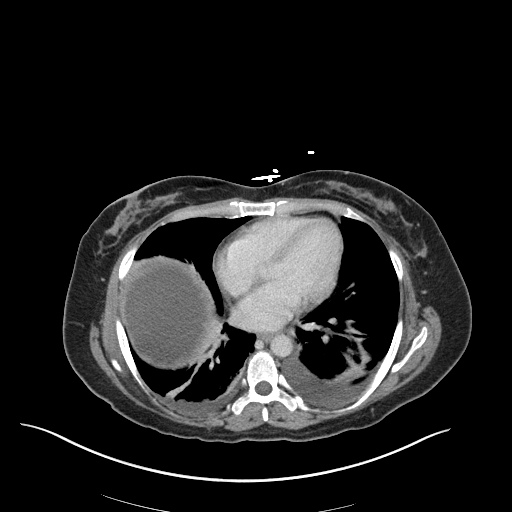

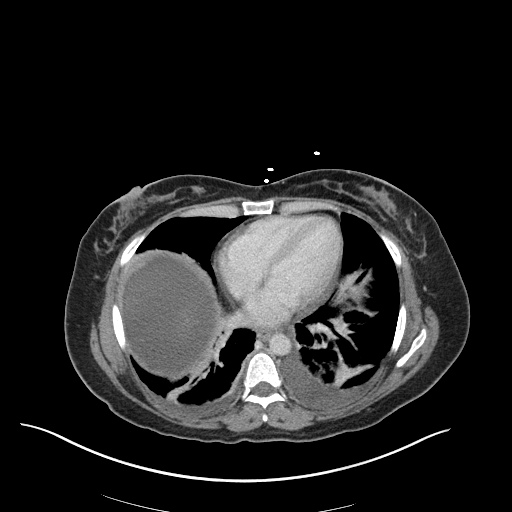

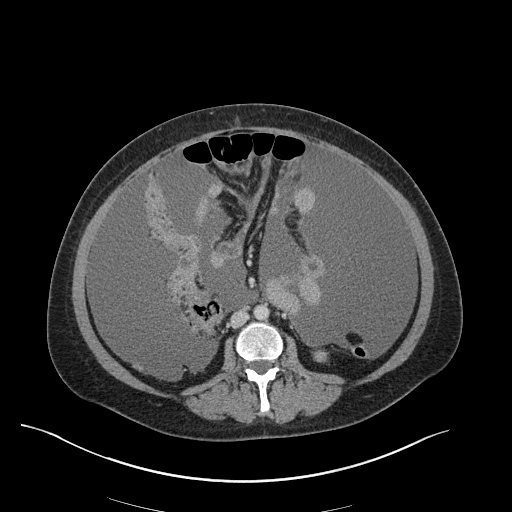

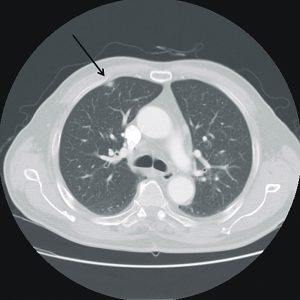

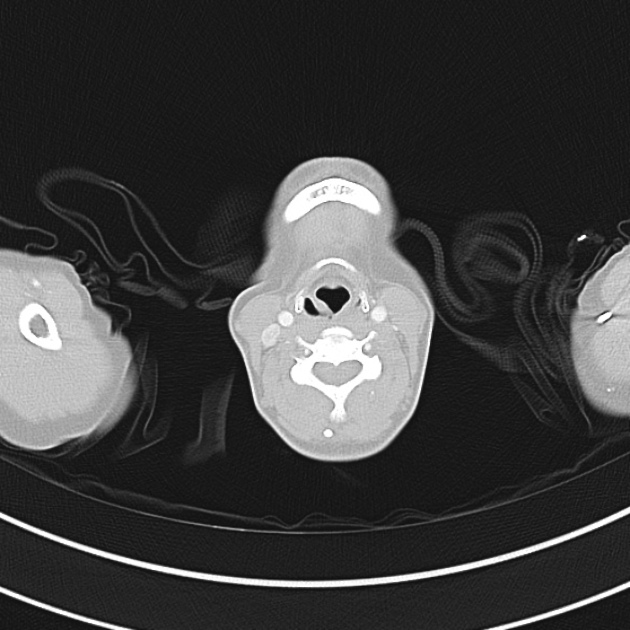

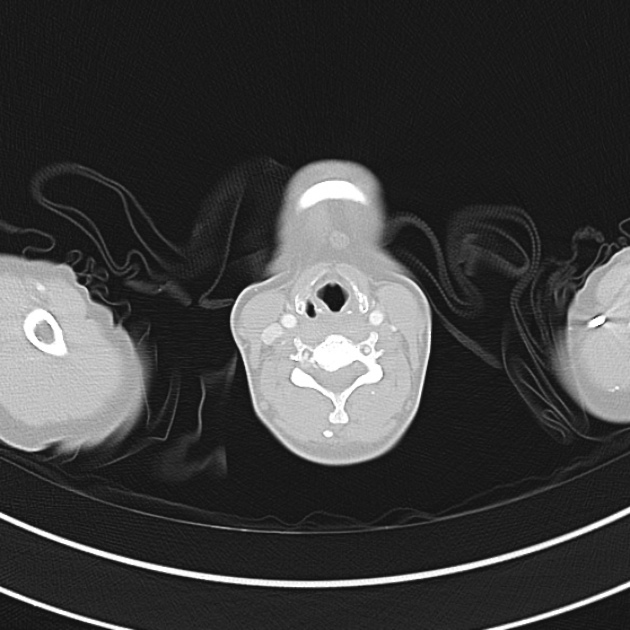

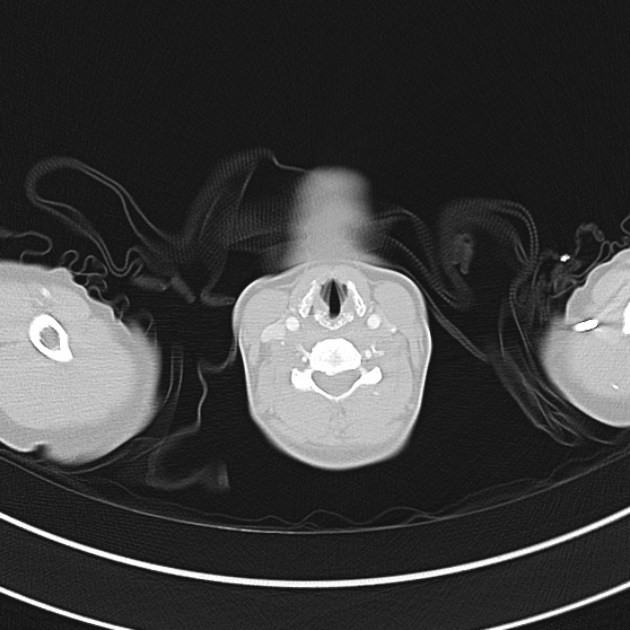

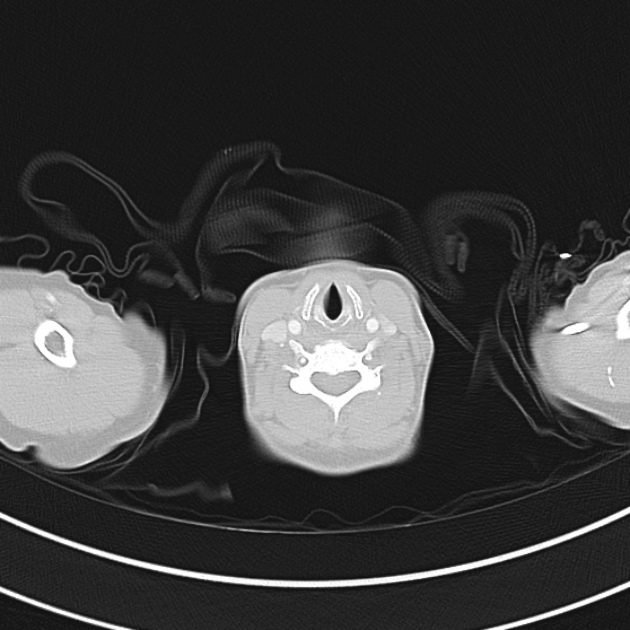

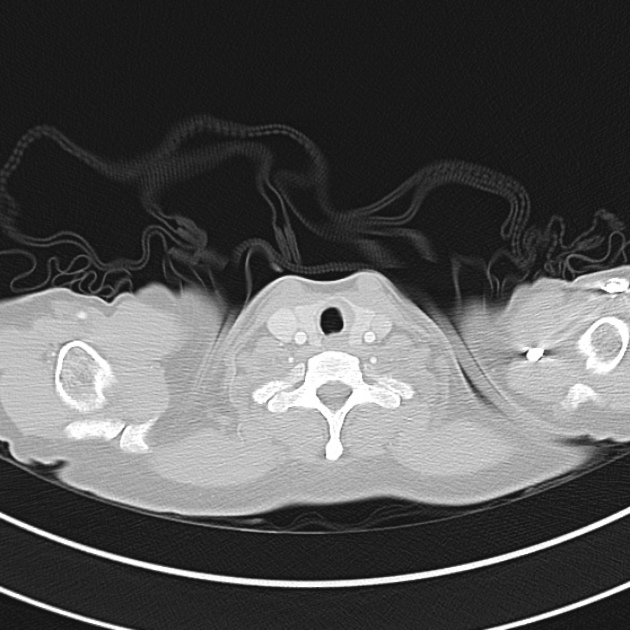

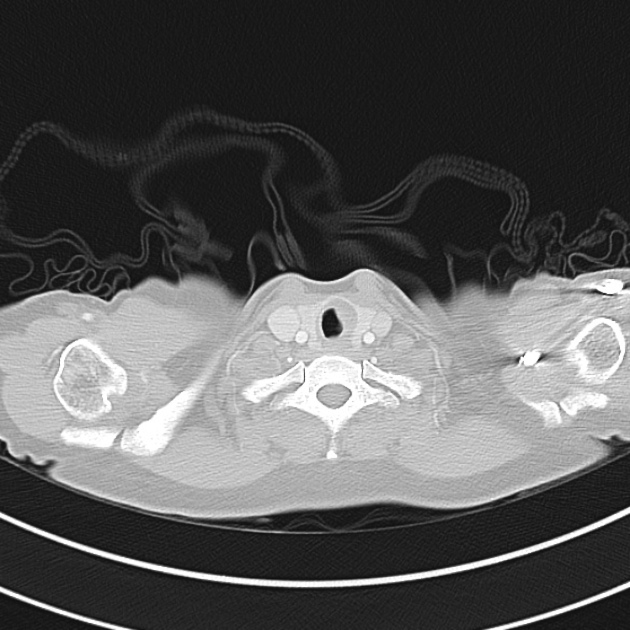

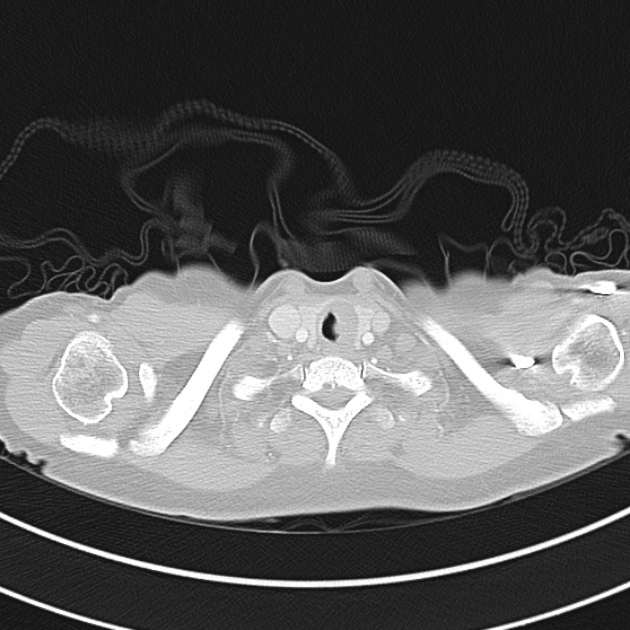

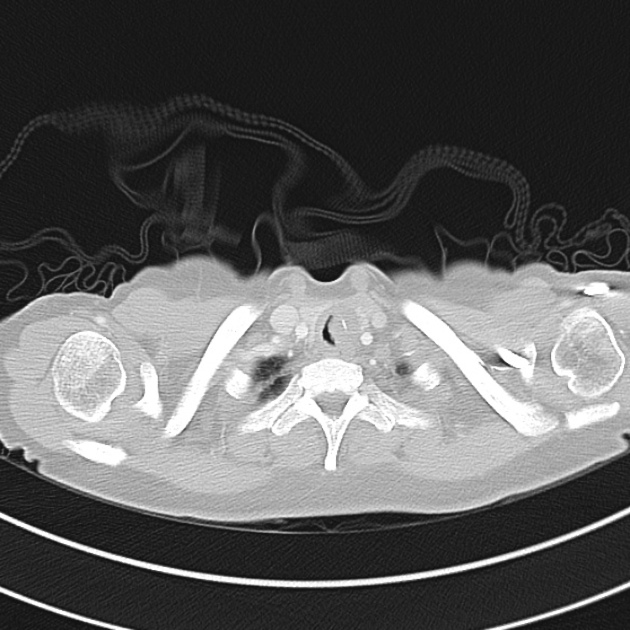

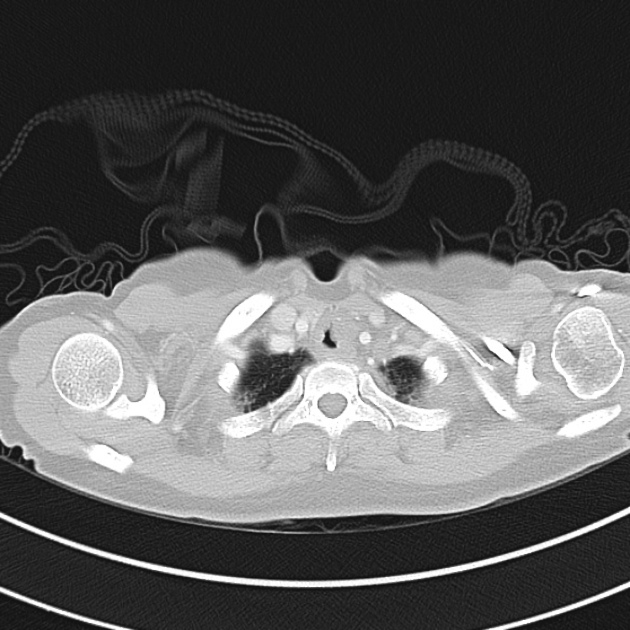

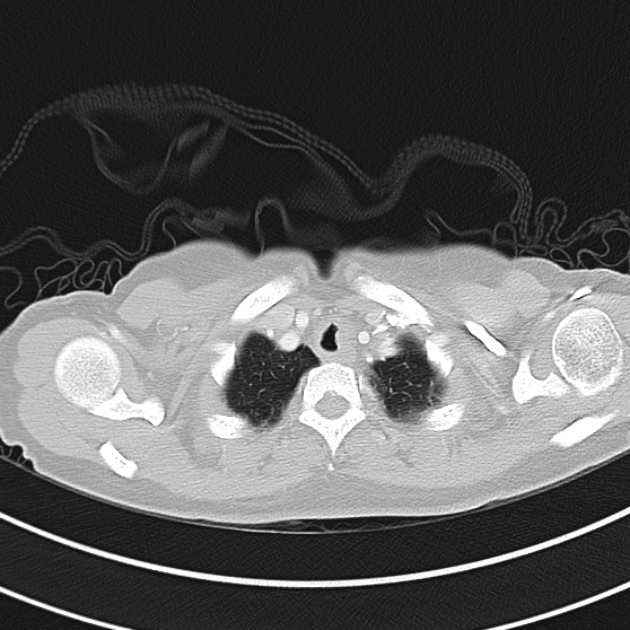

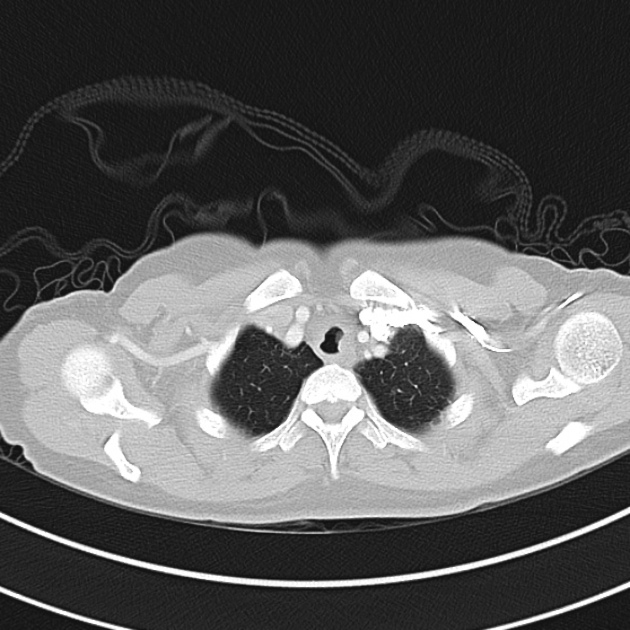

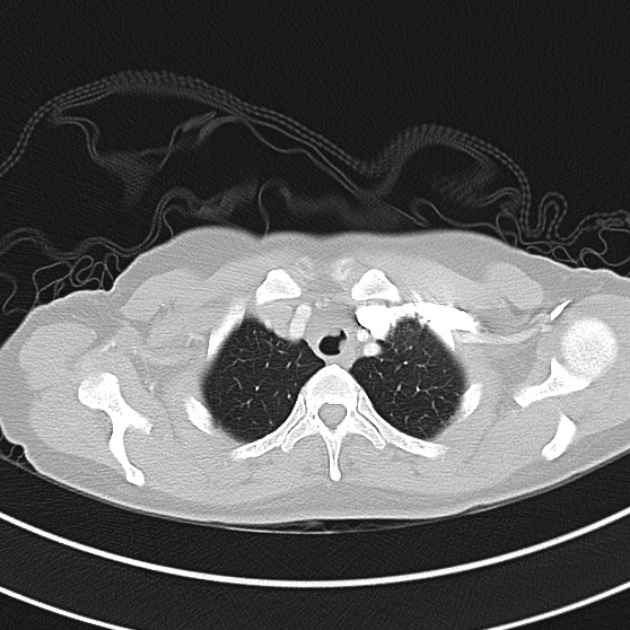

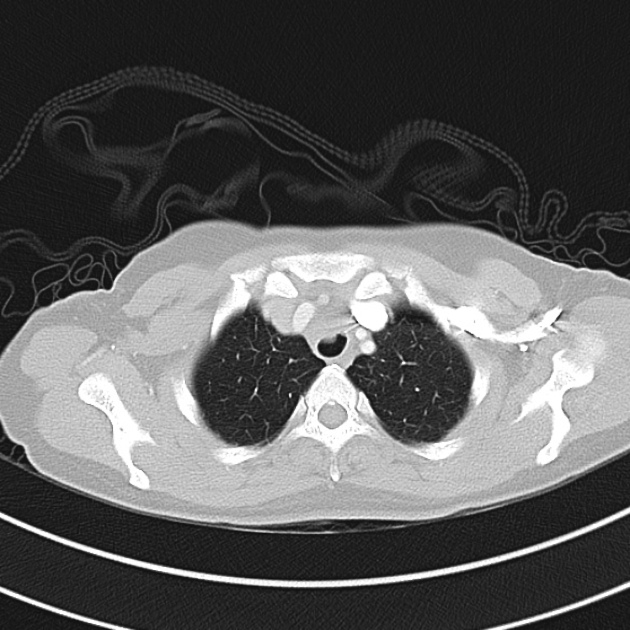

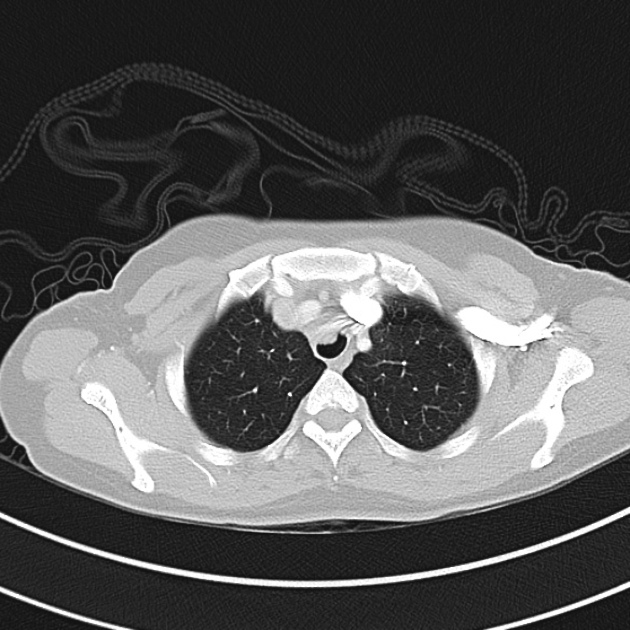

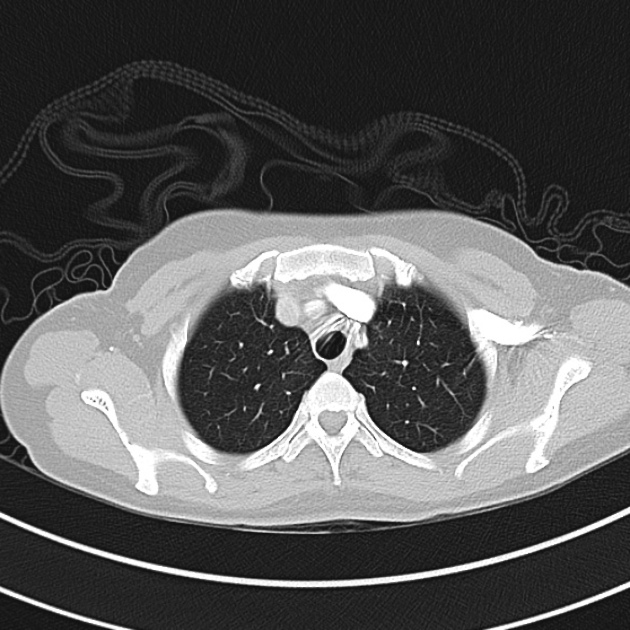

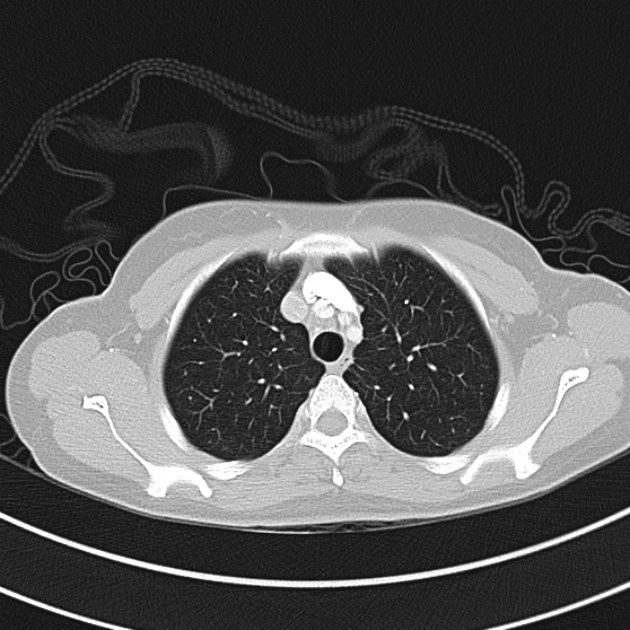

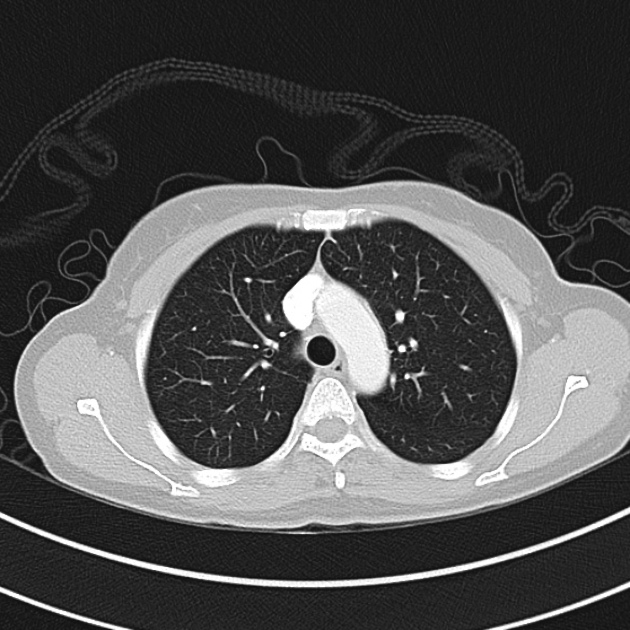

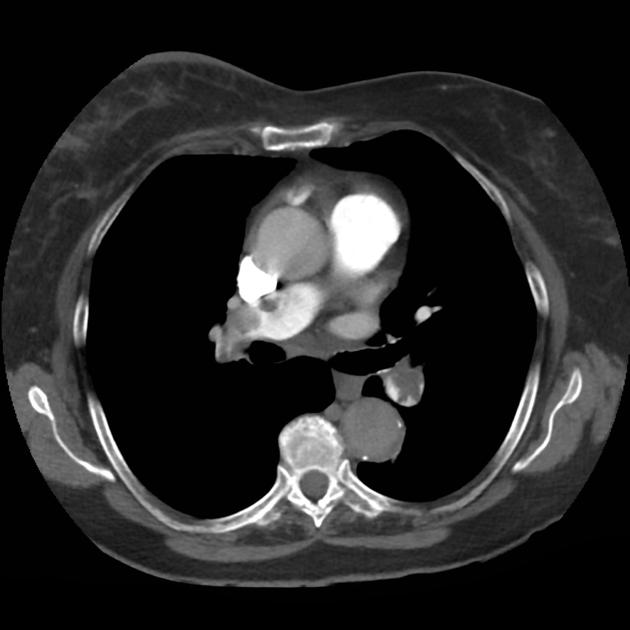

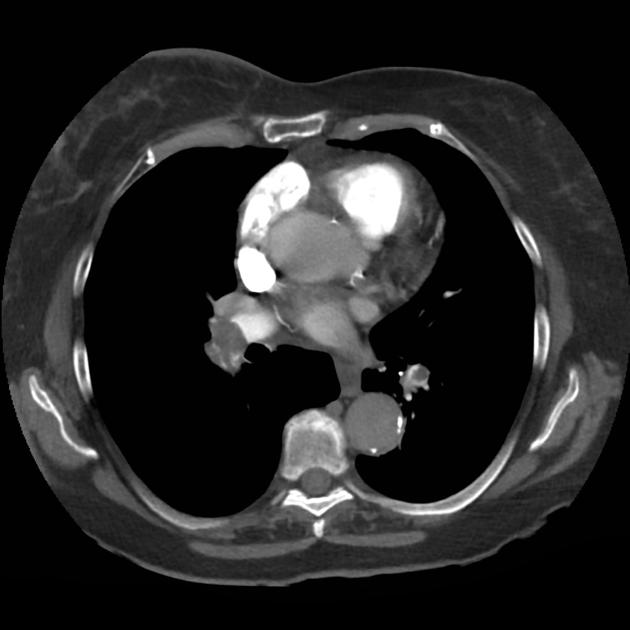

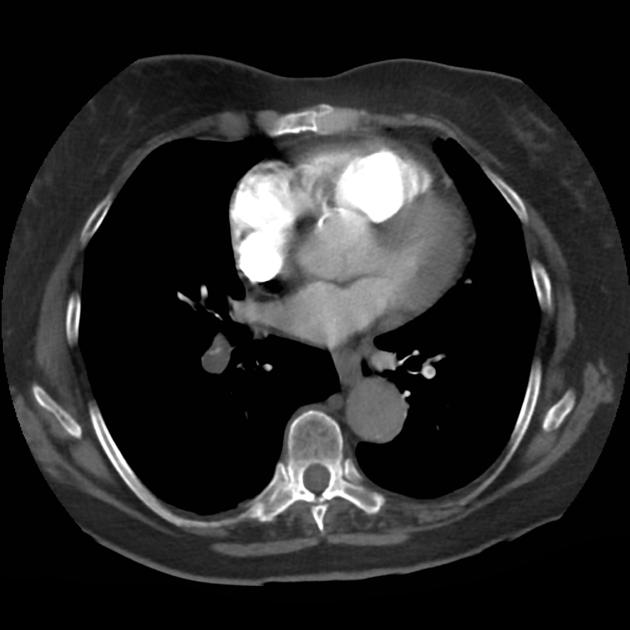

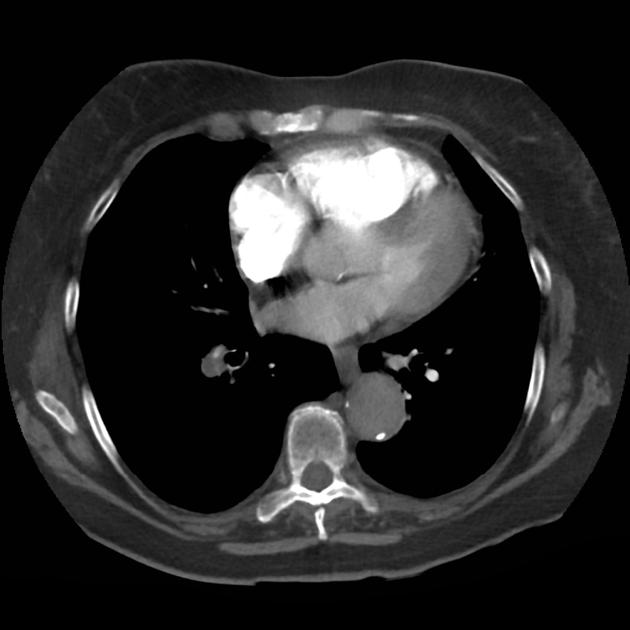

CT Chest (High-Resolution):

- Bilateral, left greater than right, pleural effusions with adjacent atelectasis and collapse versus consolidation of the left lower lobe.

- Prominent main pulmonary artery measuring 3.3 cm in diameter, which can be seen with pulmonary arterial hypertension.

TTE:

- LVEF is 50-55%.

- Impaired left ventricular relaxation, which is associated with grade I/IV or mild diastolic dysfunction.

- Moderate aortic stenosis with mild regurgitation (AVA 1.4 cm3, mean gradient 14mmHg, peak velocity 2.4 m/s).

- Severe pulmonary hypertension (est PASP 52-62mmHg).

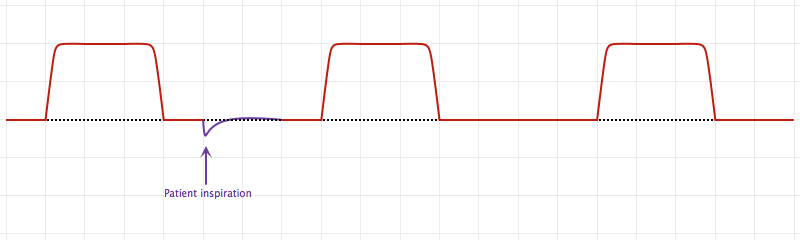

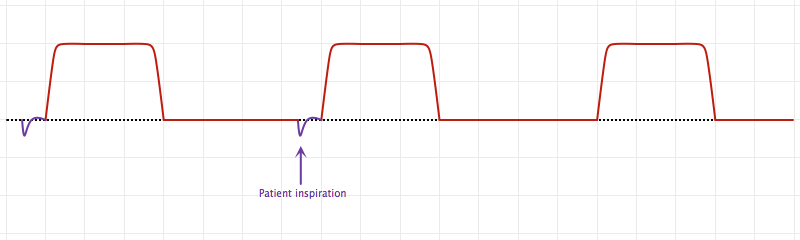

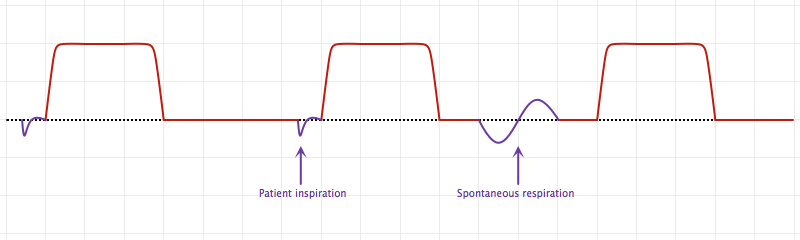

- The inferior vena cava appeared dilated and decreased <50% with respiration (RAP 10-20 mmHg).

- Minimal pericardial effusion without echocardiographic evidence of tamponade.

Assessment/Plan:

64F with history of CAD (prior MI), CHF, hypertension, CLL, hypothyroidism presented from a SNF with progressive shortness of breath, orthopnea and LE swelling, found to have bilateral (L>R) pleural effusion now s/p thoracentesis with transudative fluid.

#Acute hypoxic respiratory failure: Large pleural effusions, s/p thoracentesis with pleural fluid suggestive of transudative process. Most likely secondary to left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. Improved after thoracentesis and diuresis. High-resolution CT chest performed without evidence of autoimmune-related pulmonary fibrosis or ILD (though persistent pleural effusions, pulmonary vascular congestion).

#Pleural fluid signet cells: Identified on cytology, potentially related to history of untreated CLL or alternative primary malignancy.

#Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, decompensated: Associated with pleural effusions and hypoxemic respiratory failure. Management with diuresis.

#Pulmonary Hypertension: Severe, noted on transthoracic echocardiography, may be secondary to hypoxemia associated with pleural effusions, consider repeat imaging once euvolemic or right-heart catheterization.

#Microscopic Hematuria: No evidence of infection, no symptoms suggestive of nephrolithiasis. No casts identified or significant proteinuria. Plan for renal ultrasound.

#Rheumatoid Arthritis: History of rheumatoid arthritis, on prednisone and hydroxychloroquine. Imaging without evidence of inflammatory arthropathy, RF elevated but CCP negative. Per rheumatology, the patient’s symptoms are not consistent with RA, continuing home medications while evaluation is ongoing. Pleural effusions unlikely associated with RA as transudative, and without monocyte predominance or low glucose.

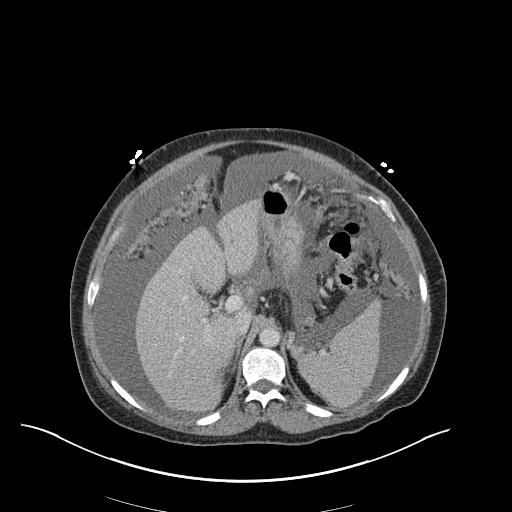

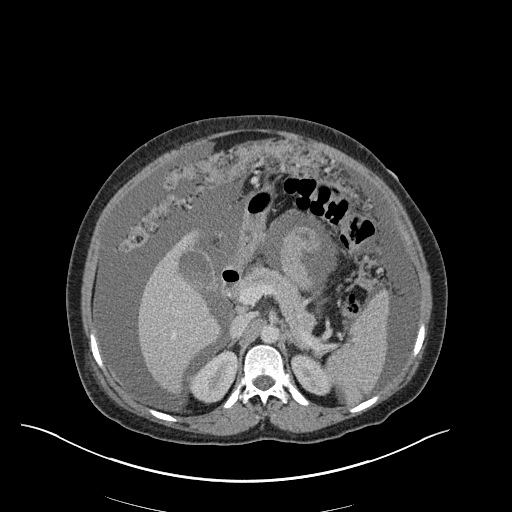

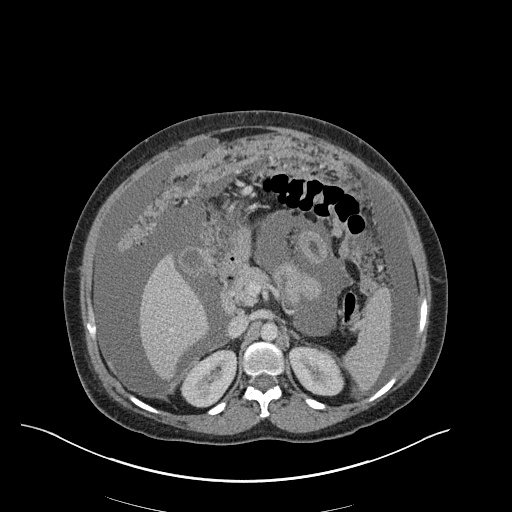

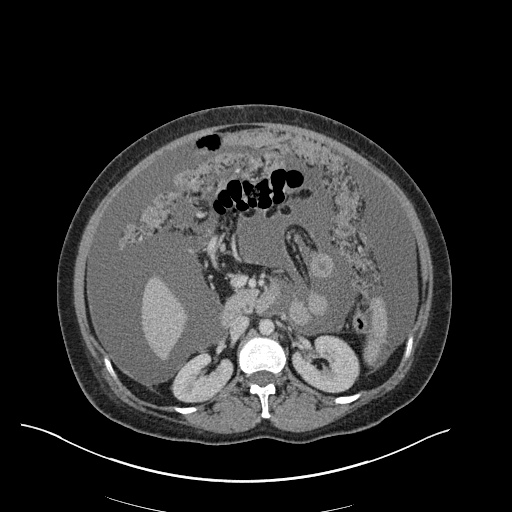

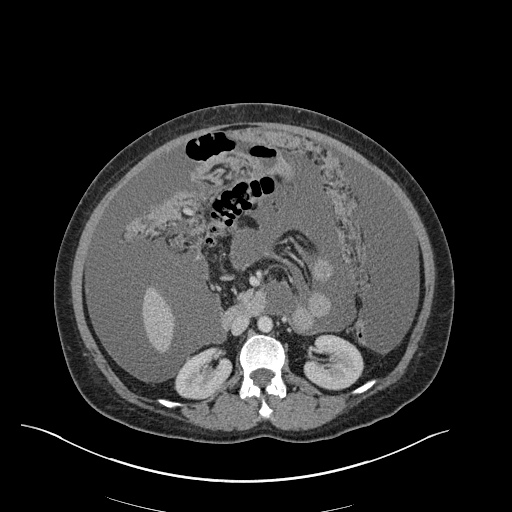

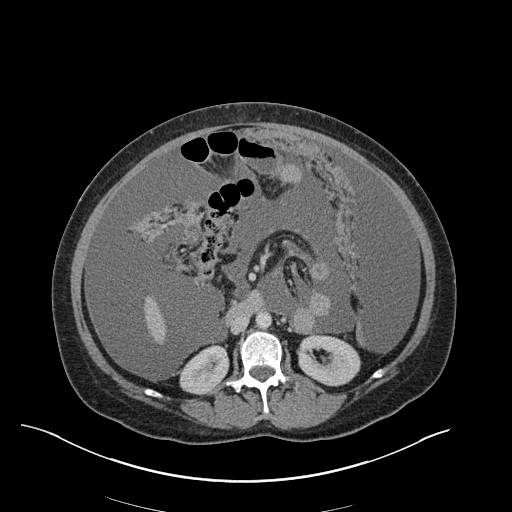

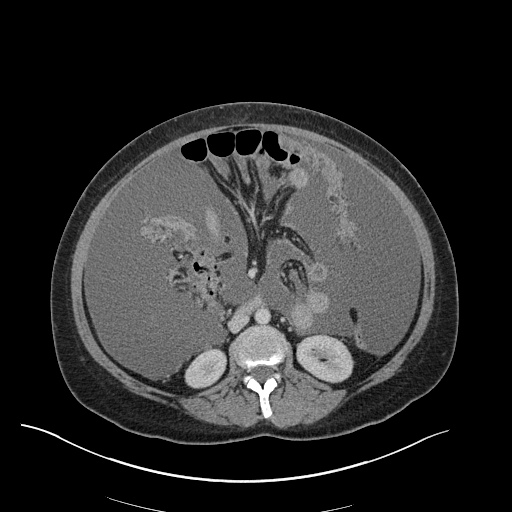

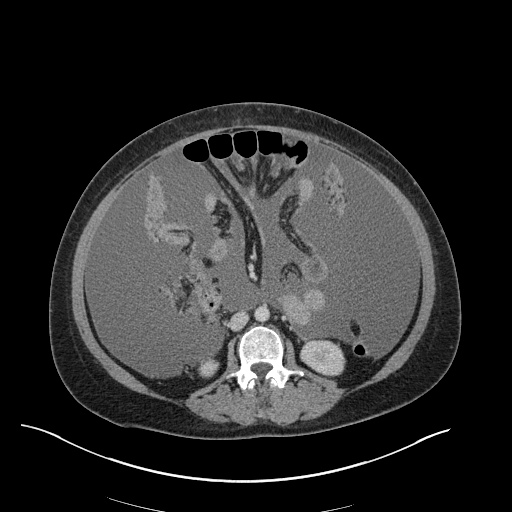

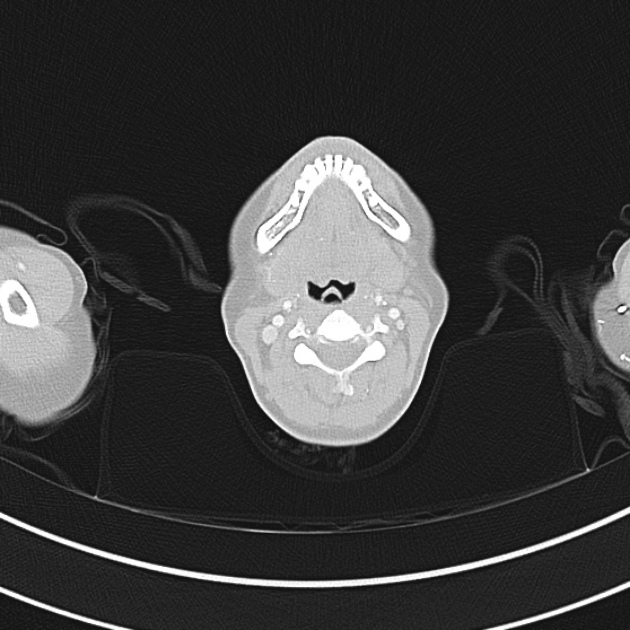

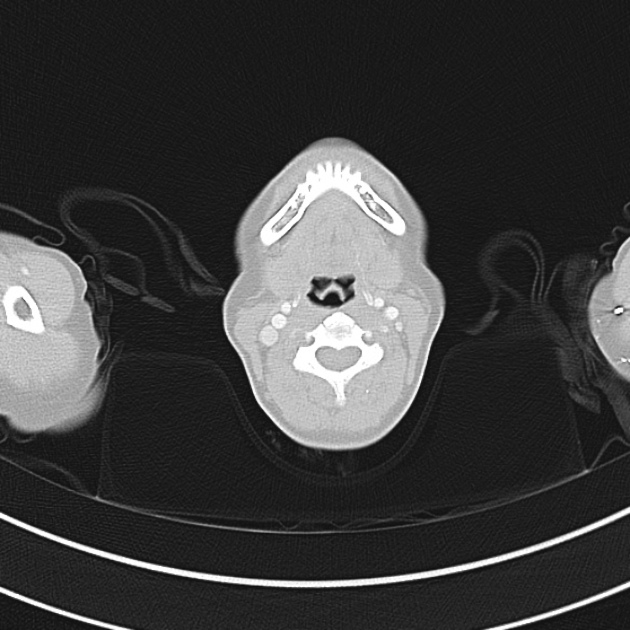

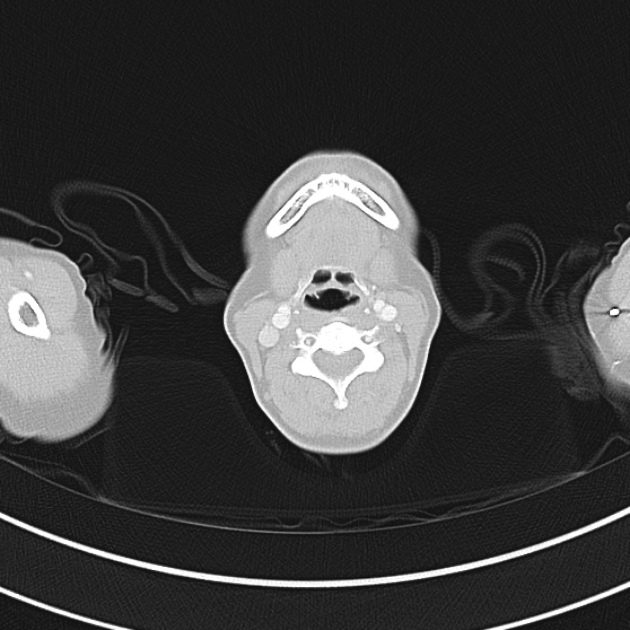

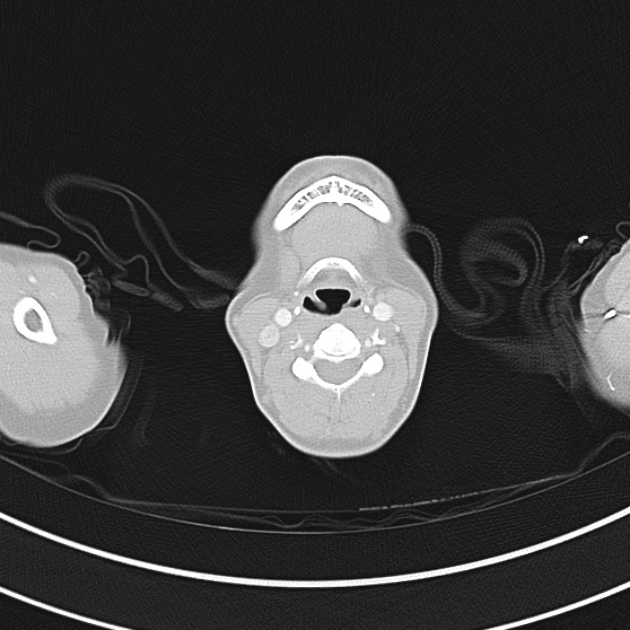

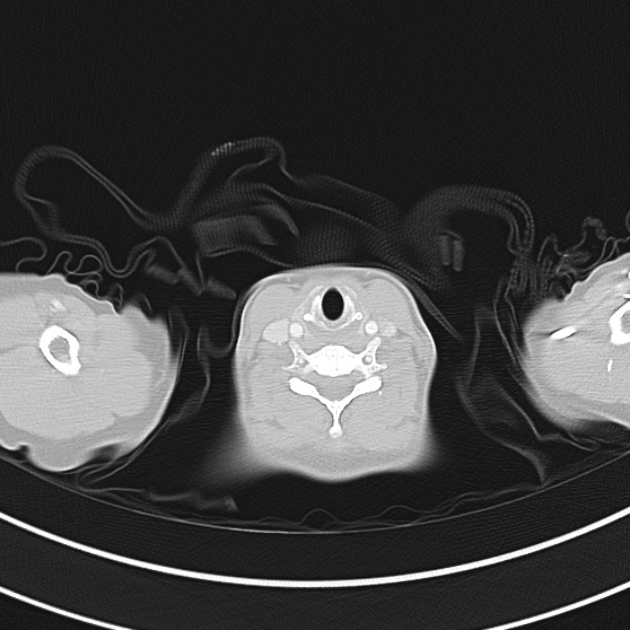

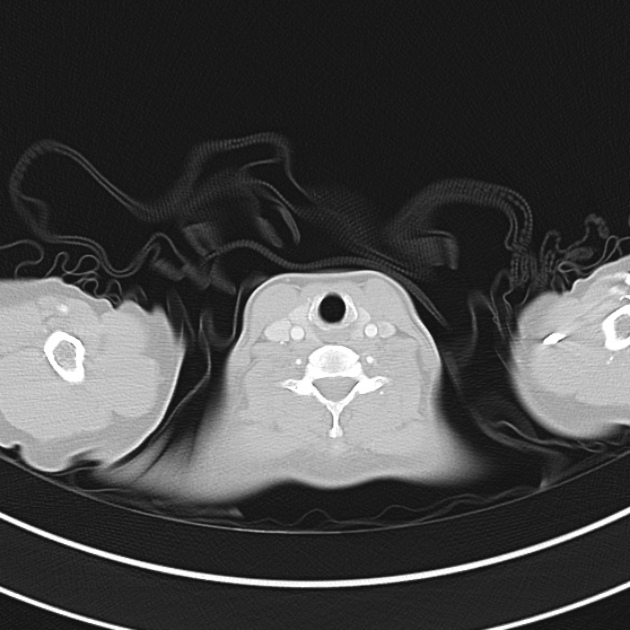

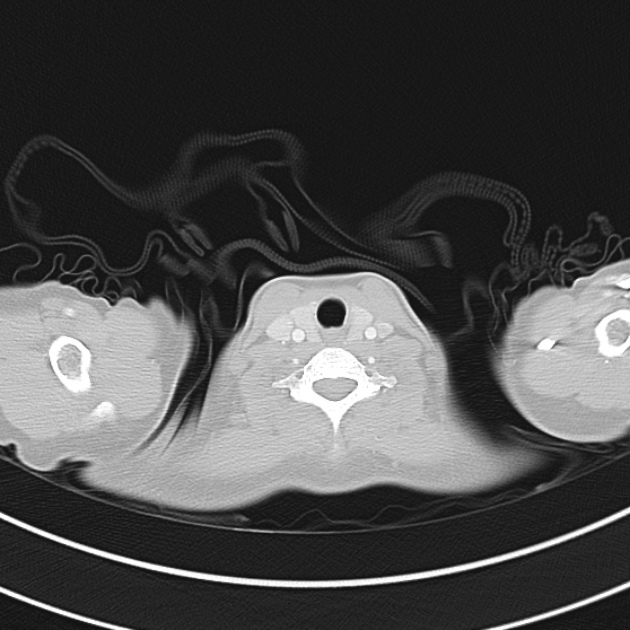

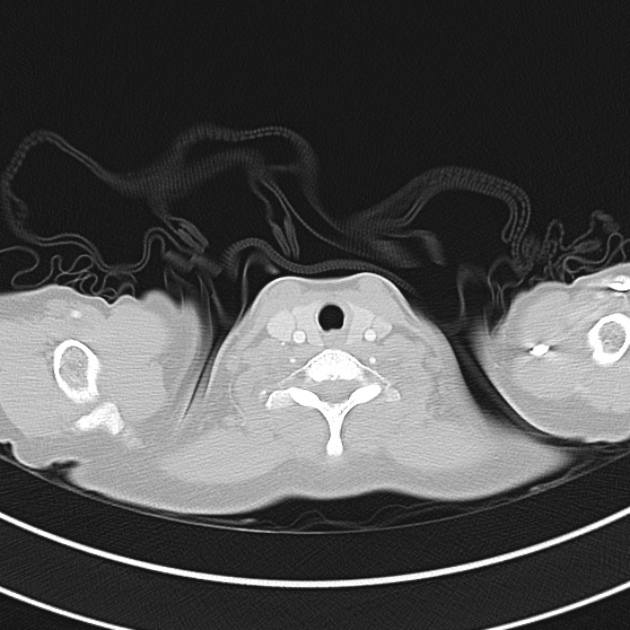

Case 2: Malignant Pleural Effusion

Within the lungs there are ground-glass opacities bilaterally, and a left pleural effusion with adjacent consolidation vs compressive atelectasis.

- Protein: 2.6 (serum: 4.9)

- LDH: 1275 (serum: 219)

- Cytology: Malignant cells

Case 3: Traumatic Thoracentesis

Moderate right pleural effusion, some fluid in non-dependent portions suggestive of loculation. Diffuse nodules and opacification in right lung with compressive atelectasis. Left pleural effusion with high density material at the posterior costophrenic angle. Left chest tube.

- Protein: 2.7 (serum 6.4)

- LDH: 344 (serum 236)

- Cell count: 100,000 RBC

Case 4: Pneumonia

Loculated right pleural effusion with foci of atelectasis and consolidative changes concerning for pneumonia. Minimal left-sided pleural effusion with consolidative changes. Enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes, possibly reactive.

- Protein: 4.3 (serum 6.7)

- LDH: 377 (serum 108)

- pH: 7.46

- Glucose: 153

- Neutrophils: 84%

Etiology of Pleural Effusions: 1

| Etiology |

Frequency (%) |

| CHF |

35 |

| Pneumonia |

22 |

| Malignancy |

15 |

| Pulmonary Embolism |

11 |

Clinical Features in the Diagnosis of Pleural Effusions and Identifying Etiology: 1,2

Pleural effusions can be easily identified on chest radiography, physical examination findings include dullness to percussion, decreased tactile fremitus and decreased (or absent) breath sounds.

- Hemoptysis: Malignancy, PE, TB

- Weight Loss: Malignancy, TB

- Ascites: Cirrhosis, ovarian cancer

- Unilateral Leg Swelling: PE

- Bilateral Leg Swelling: CHF, cirrhosis, nephrotic syndrome

- Jugular Venous Distension: CHF

Differential Diagnosis of Pleural Effusions: 1,2,3,4

References:

- Light, R. W. (2002). Clinical practice. Pleural effusion. The New England journal of medicine, 346(25), 1971–1977. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp010731

- McGrath, E. E., & Anderson, P. B. (2011). Diagnosis of pleural effusion: a systematic approach. American journal of critical care : an official publication, American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, 20(2), 119–27– quiz 128. doi:10.4037/ajcc2011685

- Thomsen, T. W., DeLaPena, J., & Setnik, G. S. (2006). Videos in clinical medicine. Thoracentesis. The New England journal of medicine (Vol. 355, p. e16). doi:10.1056/NEJMvcm053812

- Wilcox, M. E., Chong, C. A. K. Y., Stanbrook, M. B., Tricco, A. C., Wong, C., & Straus, S. E. (2014). Does this patient have an exudative pleural effusion? The Rational Clinical Examination systematic review. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association, 311(23), 2422–2431. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.5552

- WikEM: Pleural effusion

/malig_01.jpg)

/malig_02.jpg)

/malig_03.jpg)

/malig_04.jpg)

/malig_05.jpg)

/malig_06.jpg)

/malig_07.jpg)

/malig_08.jpg)

/malig_09.jpg)

/malig_10.jpg)

/malig_11.jpg)

/malig_12.jpg)

/malig_13.jpg)

/malig_14.jpg)

/trauma_01.jpg)

/trauma_02.jpg)

/trauma_03.jpg)

/trauma_04.jpg)

/trauma_05.jpg)

/trauma_06.jpg)

/trauma_07.jpg)

/trauma_08.jpg)

/trauma_09.jpg)

/trauma_10.jpg)

/trauma_11.jpg)

/trauma_12.jpg)

/trauma_13.jpg)

/trauma_14.jpg)

/trauma_15.jpg)

/trauma_16.jpg)

/trauma_17.jpg)

/trauma_18.jpg)

/trauma_19.jpg)

/pna_01.jpg)

/pna_02.jpg)

/pna_03.jpg)

/pna_04.jpg)

/pna_05.jpg)

/pna_06.jpg)

/pna_07.jpg)

/pna_08.jpg)

/pna_09.jpg)

/pna_10.jpg)

/pna_11.jpg)

/pna_12.jpg)

/pna_13.jpg)

/pna_14.jpg)

/pna_15.jpg)