Brief HPI:

A 40 year-old male with a history of diabetes presents after accidental insulin overdose. He reports inadvertently administering 50 units of rapid-acting insulin when intending to take his long-acting insulin 25 minutes prior to presentation. He is currently asymptomatic, has a normal physical examination and his point-of-care glucose is 65mg/dL.

ED Course

The patient’s insulin regimen was clarified:

- Insulin glargine 50 units SQ once daily

- Insulin aspart 1 unit per 5g carbohydrates SQ before meals

The patient administered an insulin dose sufficient to dispose of 250g of carbohydrates with an impending peak action within minutes. The required dose of parenteral dextrose would require potentially-toxic1,2 solution concentrations (one liter of D25 or 10 ampules of D50) and there was insufficient time for central venous catheter placement. Moreover, the patient was awake and asymptomatic – able to tolerate oral intake. Juice boxes containing 15g of carbohydrates each were located and the patient drank 16-17 boxes while undergoing serial glucose measurements. His blood glucose ranged between 70mg/dL and 150mg/dL and he was discharged after an uneventful 6-hour observation.

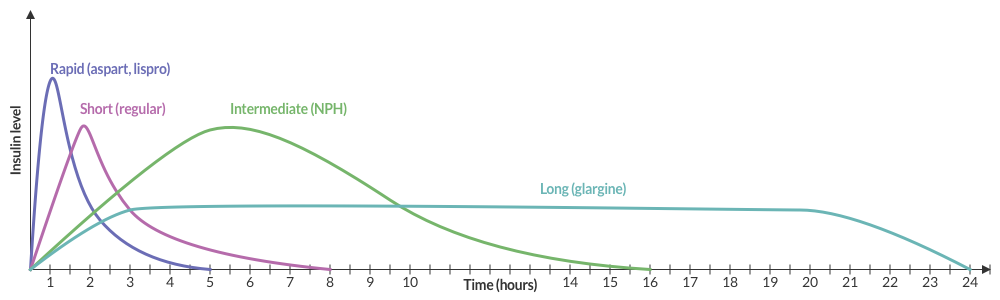

Insulin Pharmacokinetics3

Insulin and Carbohydrates

The effects of both insulin and carbohydrate ingestion on blood glucose are individualized. If known, the patient’s insulin:carbohydrate ratio can be used to anticipate the effect of overdose. Alternatively, their mealtime dose and carbohydrate allowance can be used.

Very broadly, one gram of carbohydrates increases blood glucose by 3-5mg/dL and one unit of insulin disposes of 10 grams of carbohydrates (or reduces blood glucose by 30-50mg/dL).4

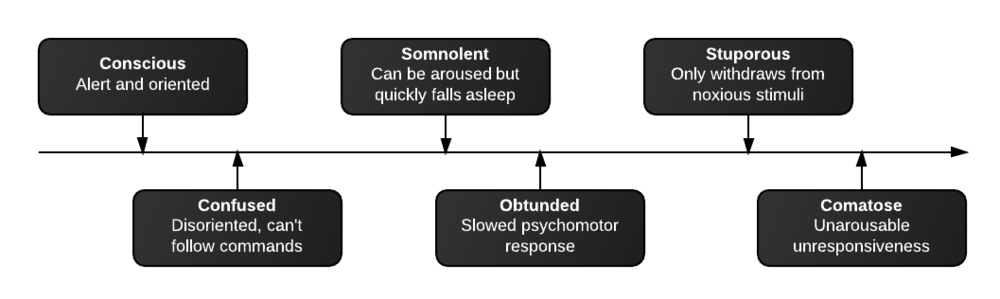

Symptoms

- Autonomic: tremor, palpitations, anxiety, diaphoresis

- Neuroglycopenic: cognitive impairment, psychomotor, seizure, coma

Diagnosis

- Serum glucose <60mg/dL

- Generally symptomatic at <55mg/dL though threshold is variable depending on chronicity

- Whipple Triad:

- Symptoms suggestive of hypoglycemia

- Low glucose

- Resolution of symptoms after administration of glucose

Differential Diagnosis of Hypoglycemia

Common Anti-hyperglycemic Drugs and Pharmacology

| Drug | Pharmacology | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset | Peak | Duration | |

Rapid-acting insulin

|

15-30min | 1-2h | 3-5h |

Short-acting insulin

|

30-60min | 2-4h | 6-10h |

Intermediate-acting insulin

|

1-3h | 4-12h | 18-24h |

Long-acting insulin

|

2-4h | None | 24h |

Sulfonylurea

|

– | 2-6h | 12-24h |

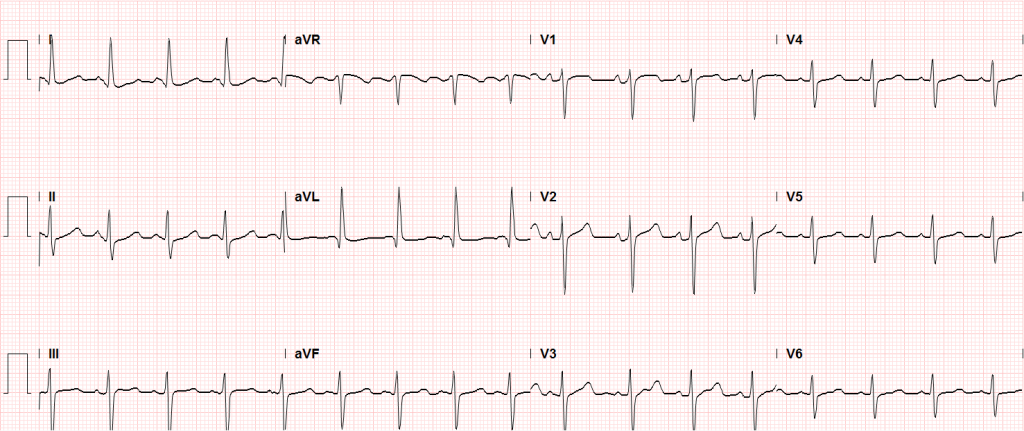

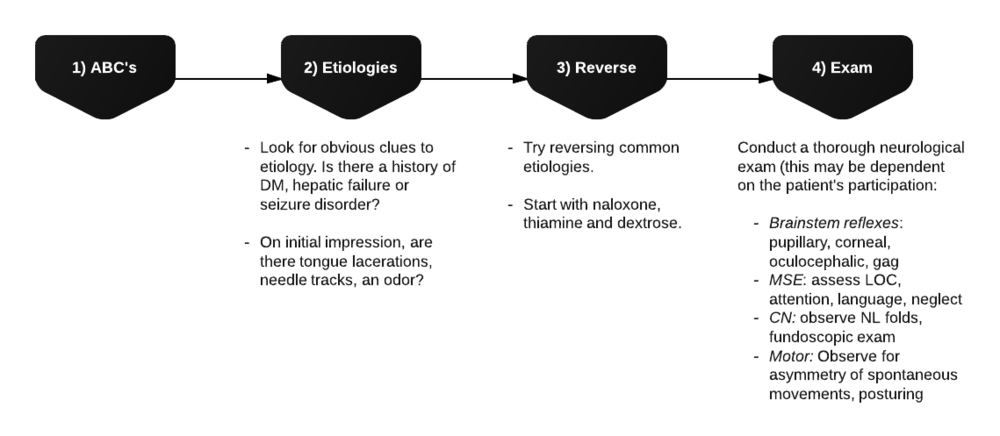

Evaluation of Hypoglycemia

Patients with known diabetes who are not systemically ill and can identify a clear precipitant, no extensive workup is required. In severely ill patients, consider:

- BMP

- LFT

- EtOH

- Infectious workup: CXR, UA, urine and blood cultures

- ECG, troponin

- Other studies: insulin, C-peptide, pro-insulin, glucagon, growth hormone, cortisol, B-OH, insulin antibodies

Management and Monitoring

References:

- Kuwahara T, Asanami S, Kubo S. Experimental infusion phlebitis: tolerance osmolality of peripheral venous endothelial cells. Nutrition. 1998;14(6):496-501.

- Wiegand R, Brown J. Hyaluronidase for the management of dextrose extravasation. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(2):257.e1-2.

- Hirsch IB. Insulin analogues. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(2):174-183.

- Your Insulin Therapy. (2004). Am Fam Physician, 70(3), 511-512.

- Self, W. H., & McNaughton, C. D. (2013). Hypoglycemia. In Emergency Medicine (2nd ed., pp. 1379-1390). Elsevier.

- Service, FJ. Hypoglycemia in adults: Clinical manifestations, definition, and causes. In: UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (Accessed on March 18, 2016.)

- Service FJ. Hypoglycemic disorders. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(17):1144–1152. doi:10.1056/NEJM199504273321707.

- Krinsley JS, Grover A. Severe hypoglycemia in critically ill patients: risk factors and outcomes. Critical Care Medicine. 2007;35(10):2262–2267. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000282073.98414.4B.

- Lacherade J-C, Jacqueminet S, Preiser J-C. An overview of hypoglycemia in the critically ill. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3(6):1242–1249.