Brief HPI:

An approximately 80-year-old male with unknown medical history is brought to the emergency department from a skilled nursing facility after unwitnessed arrest – EMS providers established return of spontaneous circulation after chest compressions and epinephrine. On arrival, the patient was hypotensive (MAP 40mmHg) and hypoxic (SpO2 85%) with mask ventilation. The patient was intubated, resuscitated with intravenous fluids and started on vasopressors. Imaging demonstrated lung consolidation consistent with multifocal pneumonia versus aspiration. Laboratory studies were obtained:

- CBC: WBC: 49.2 (N: 64%, Bands: 20%)

- ABG: pH: 7.07, pCO2: 73mmHg

- Lactate: 9.1mmol/L

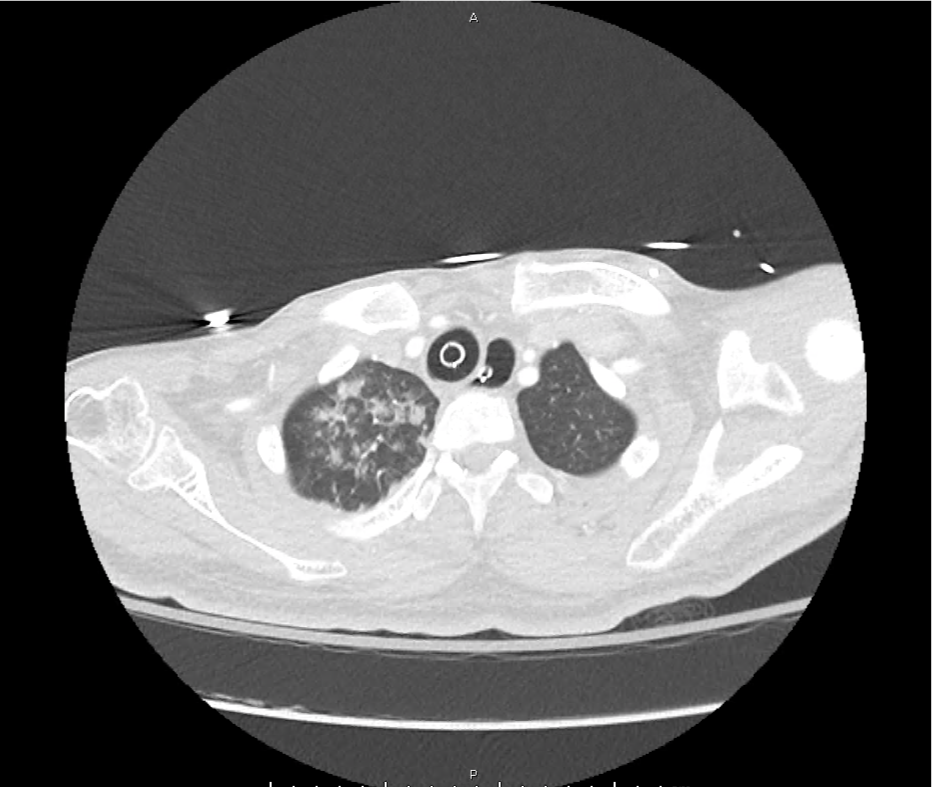

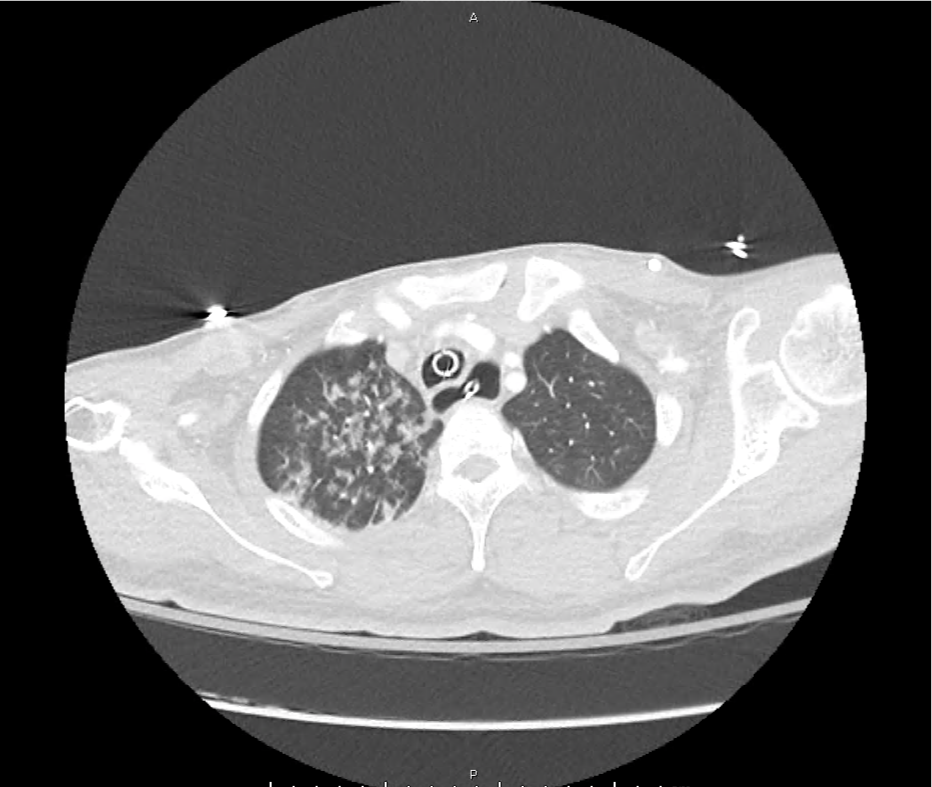

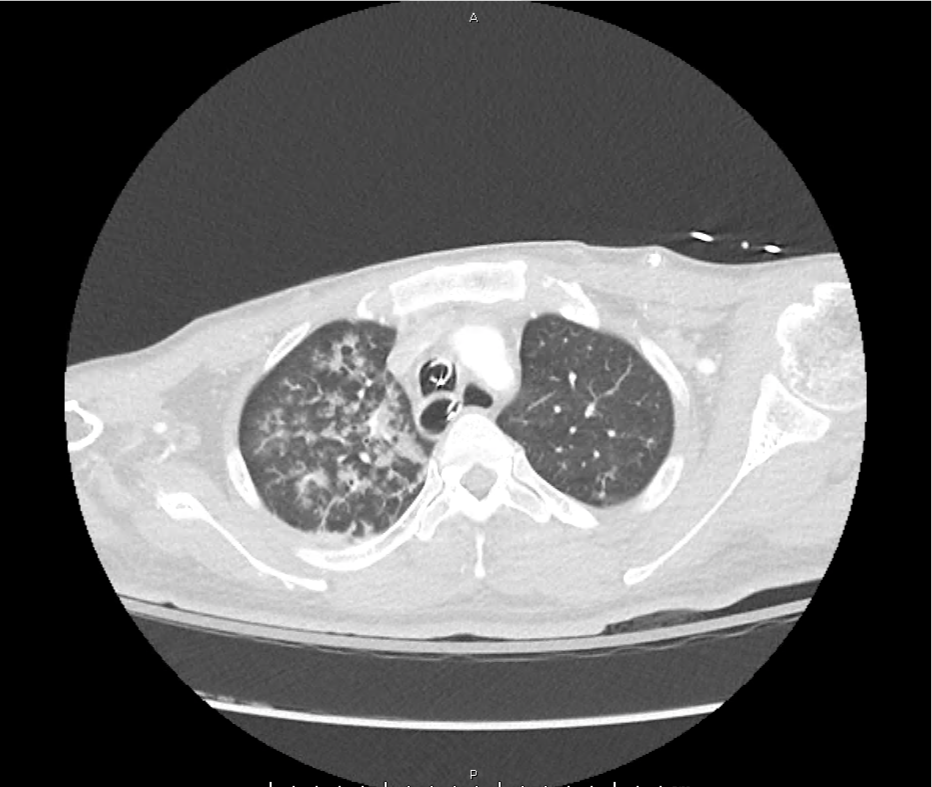

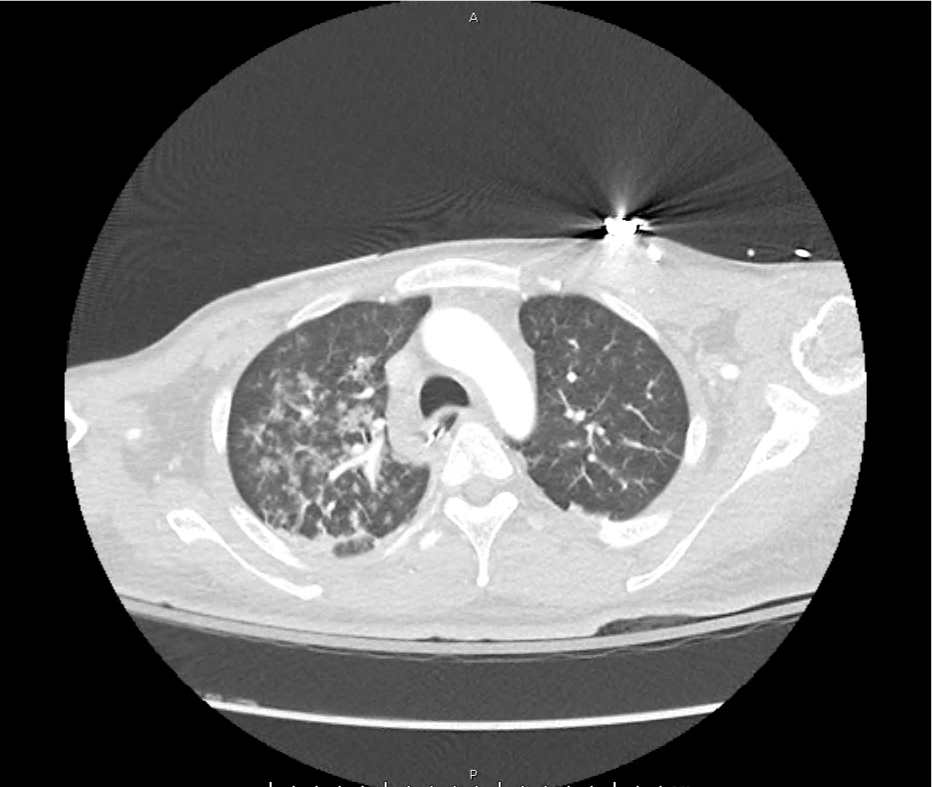

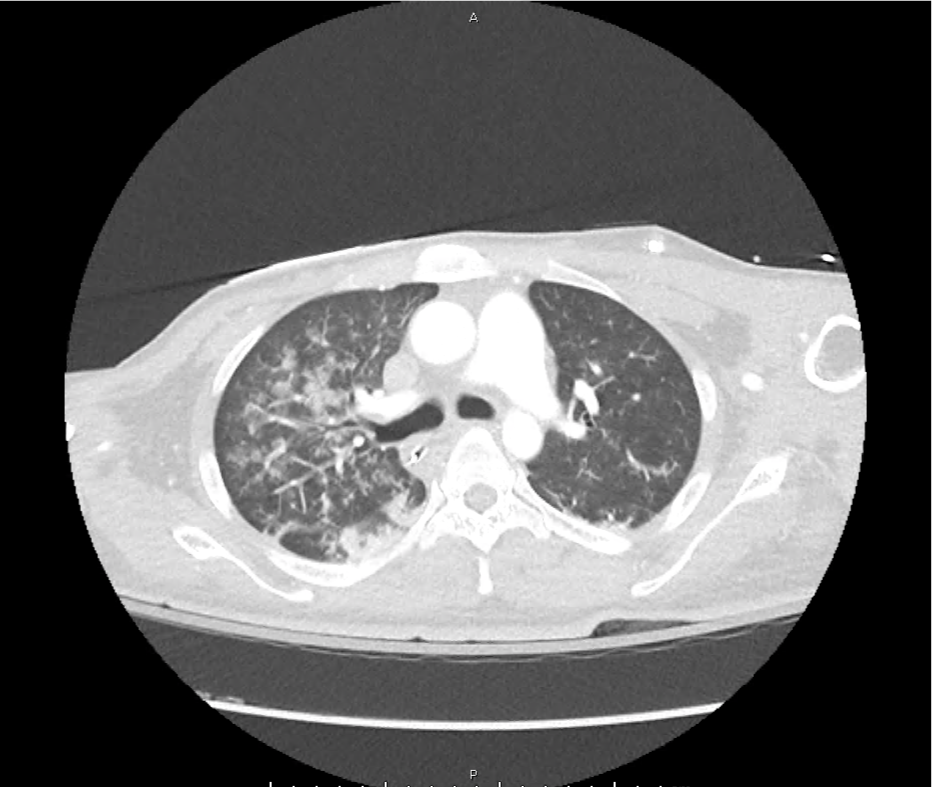

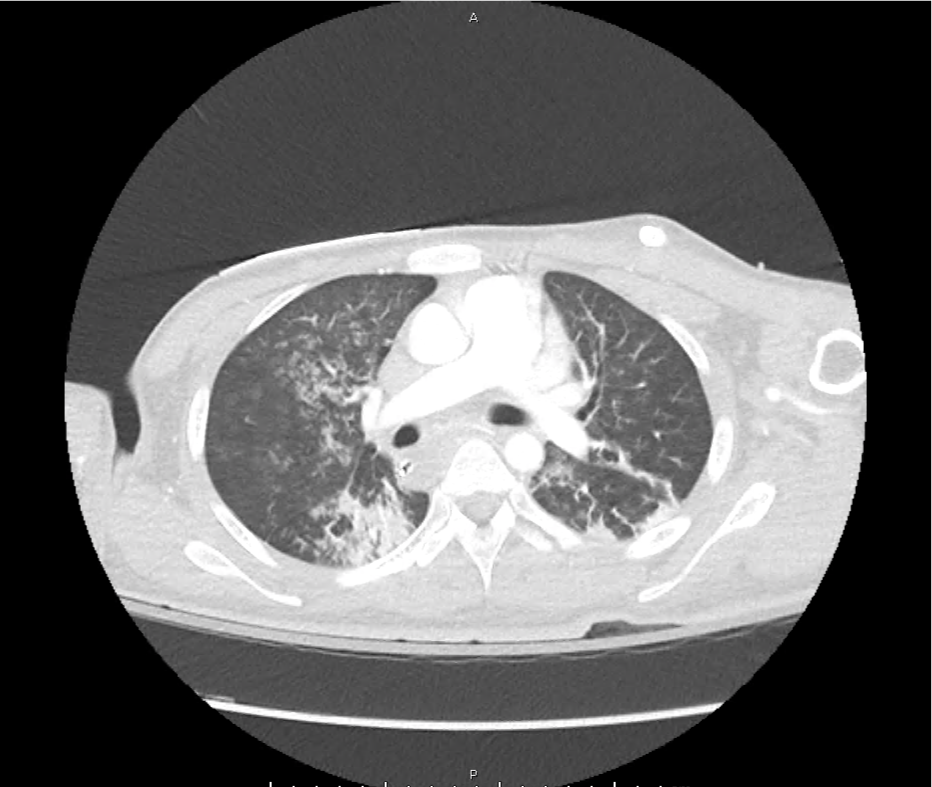

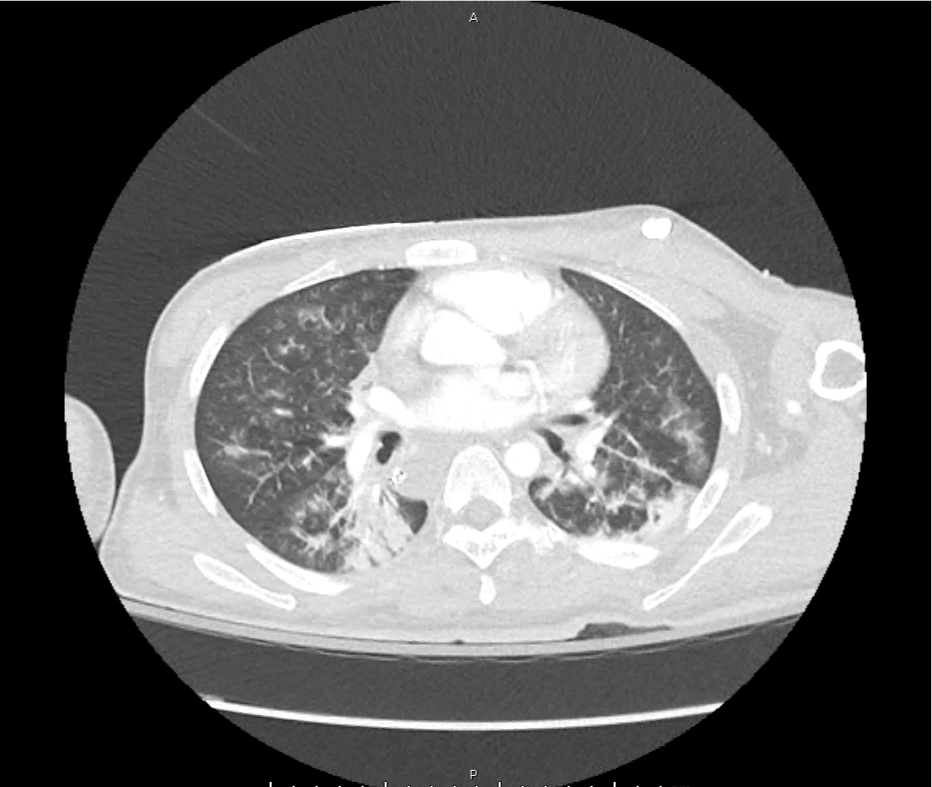

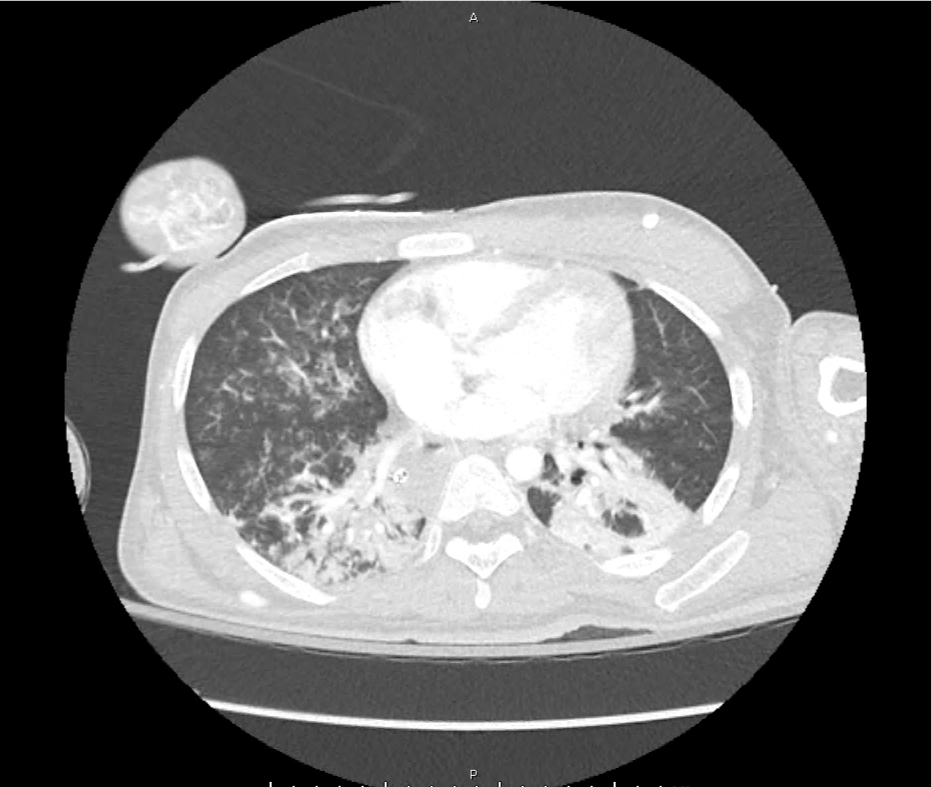

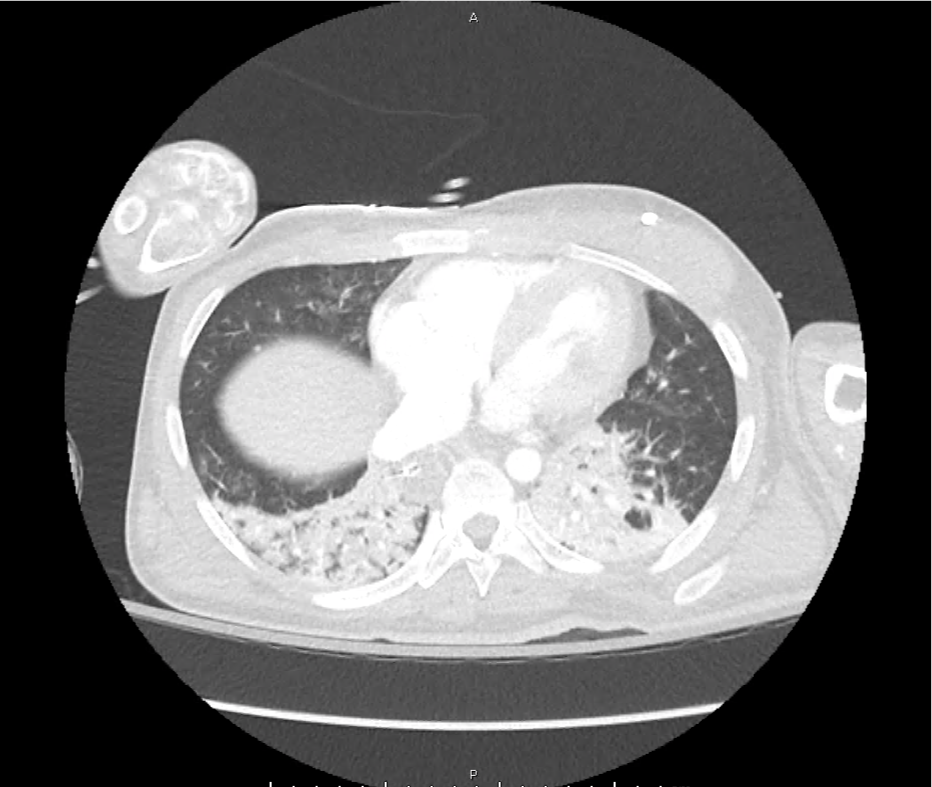

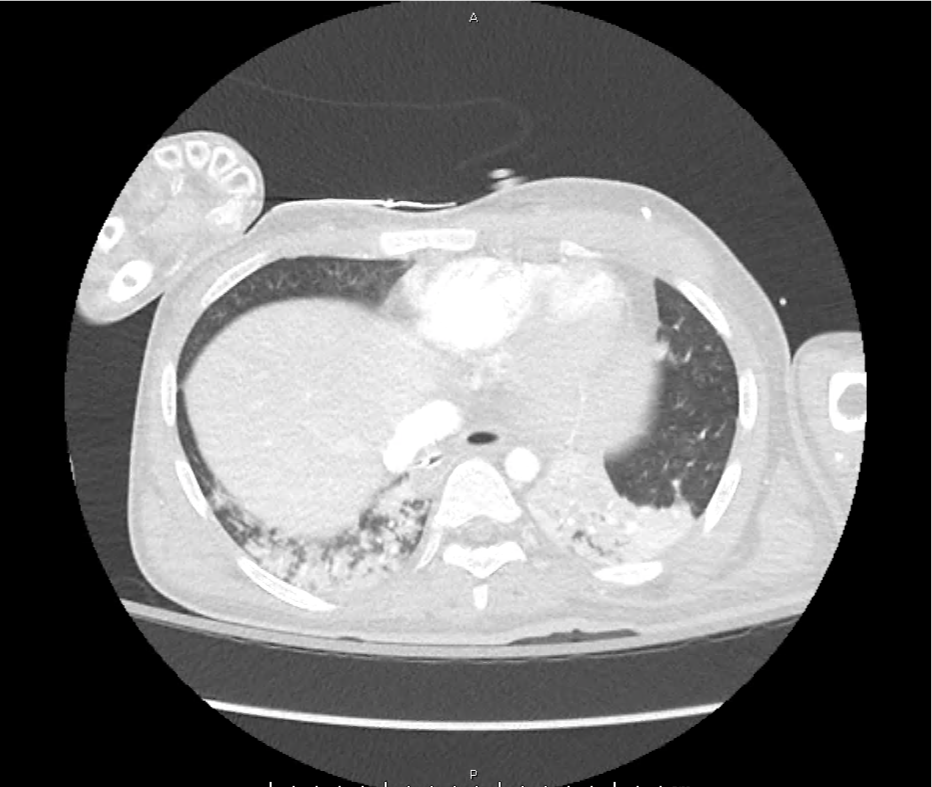

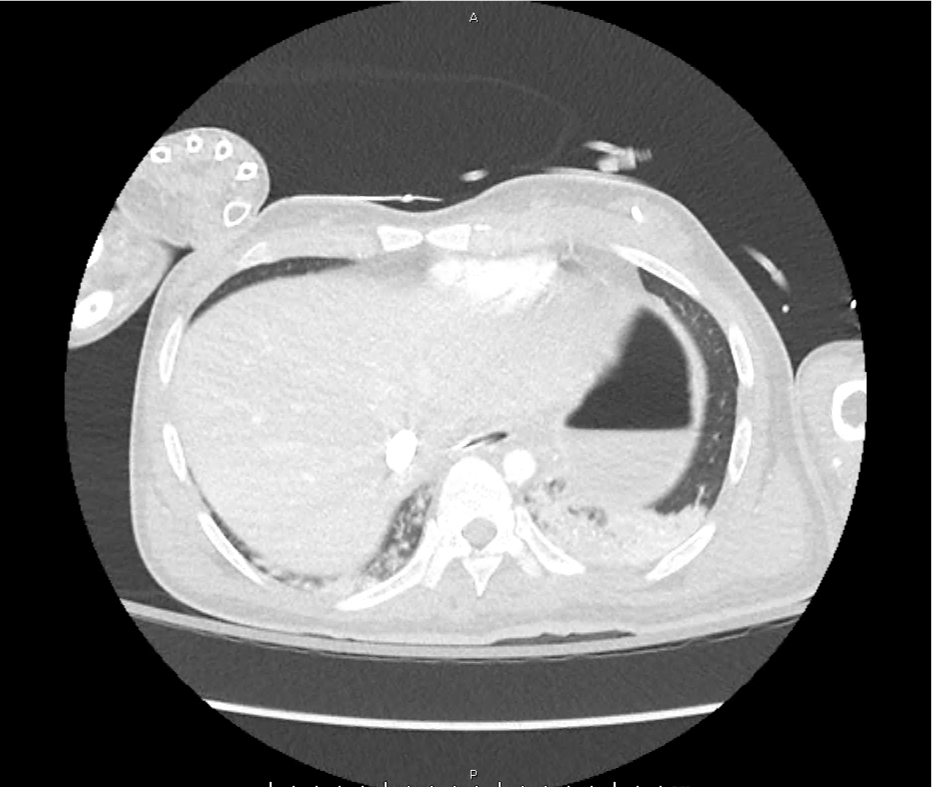

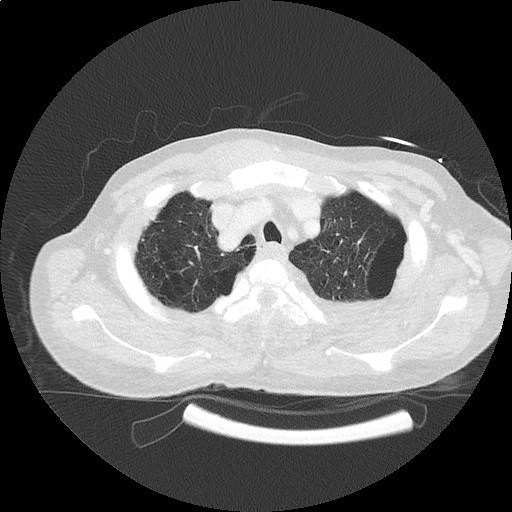

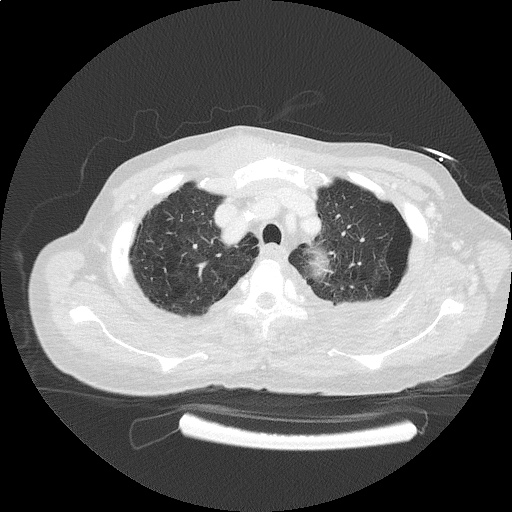

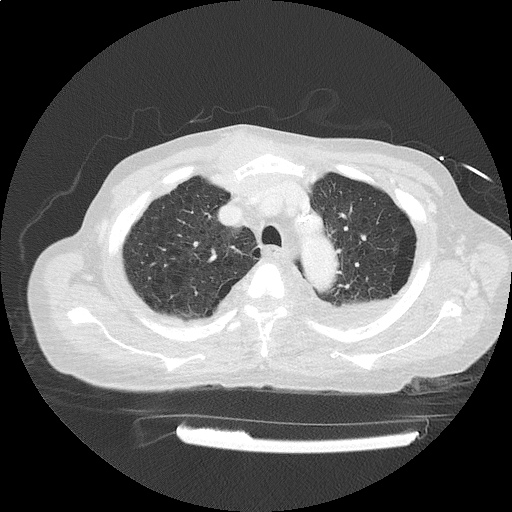

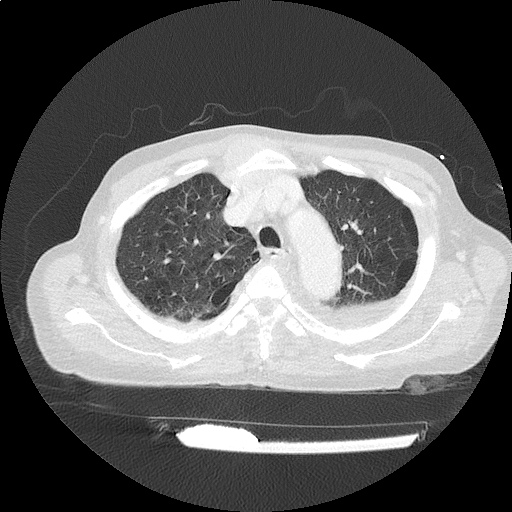

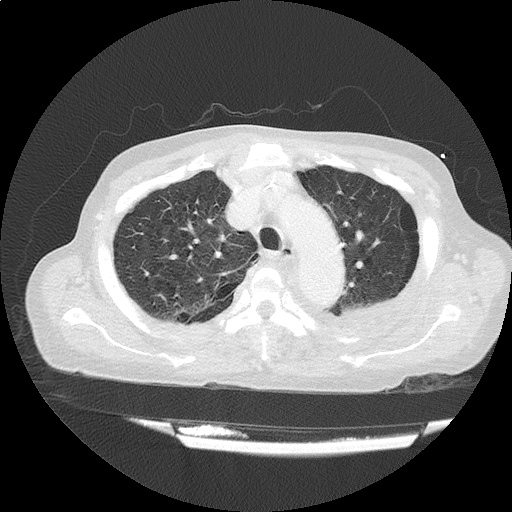

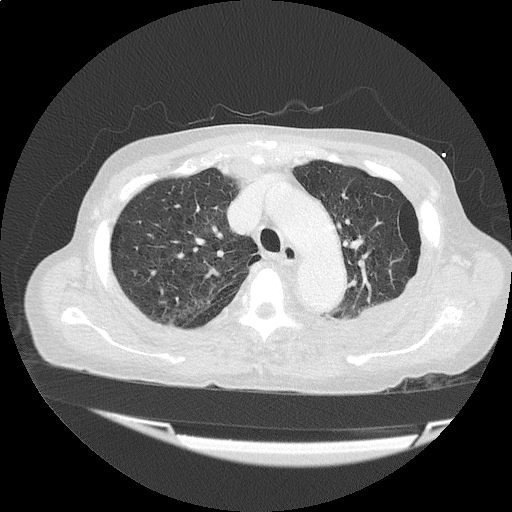

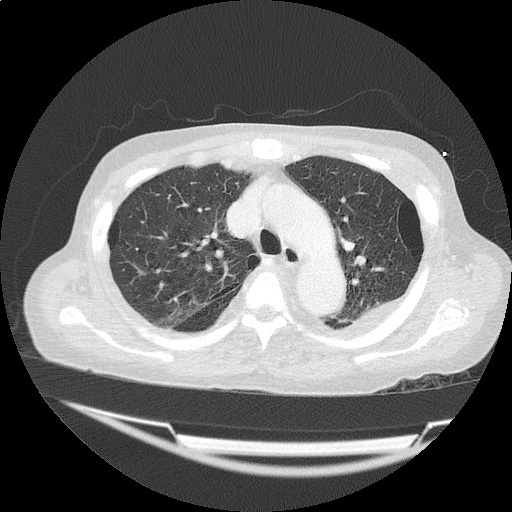

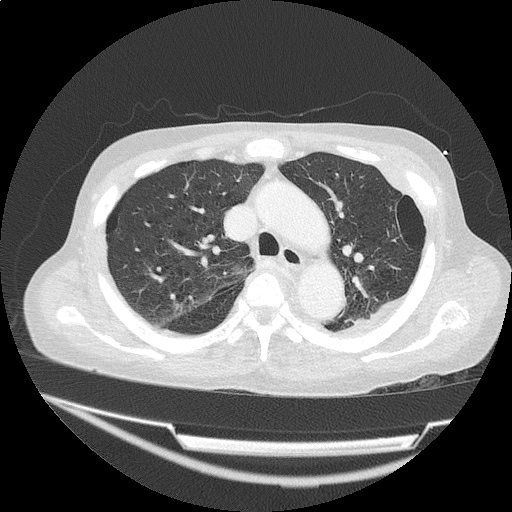

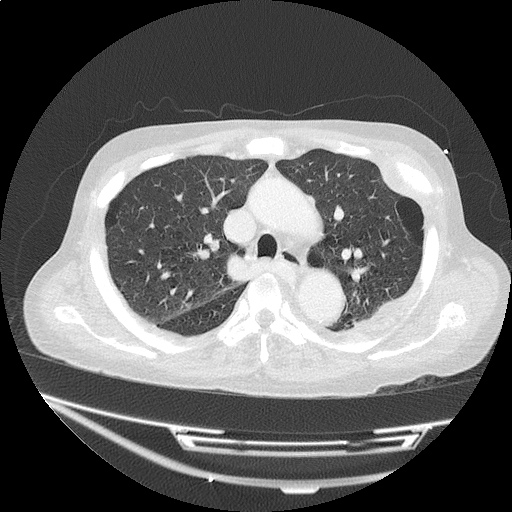

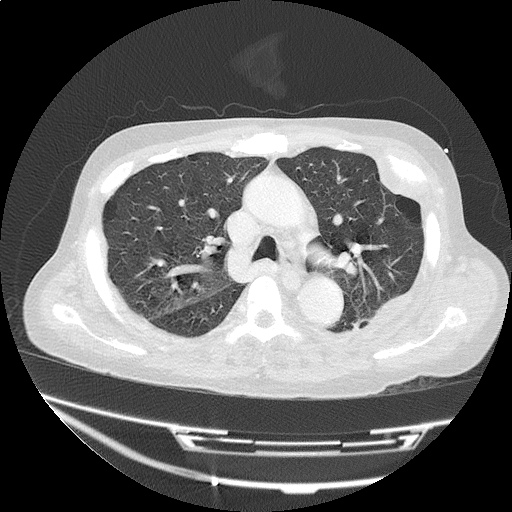

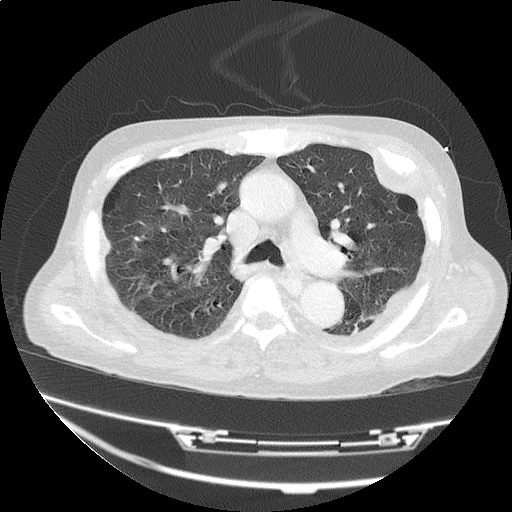

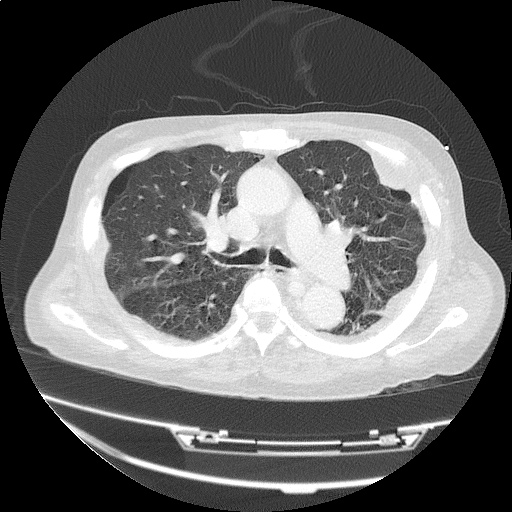

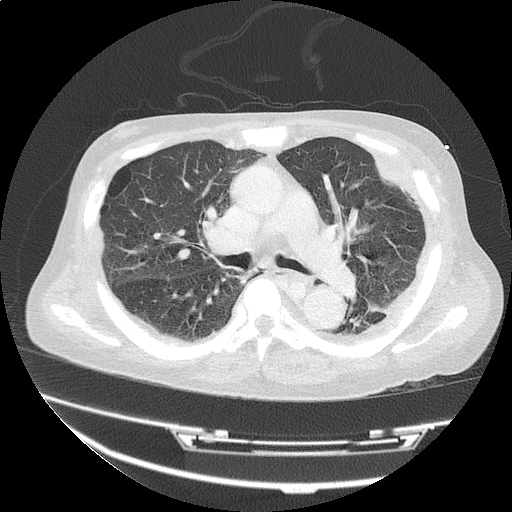

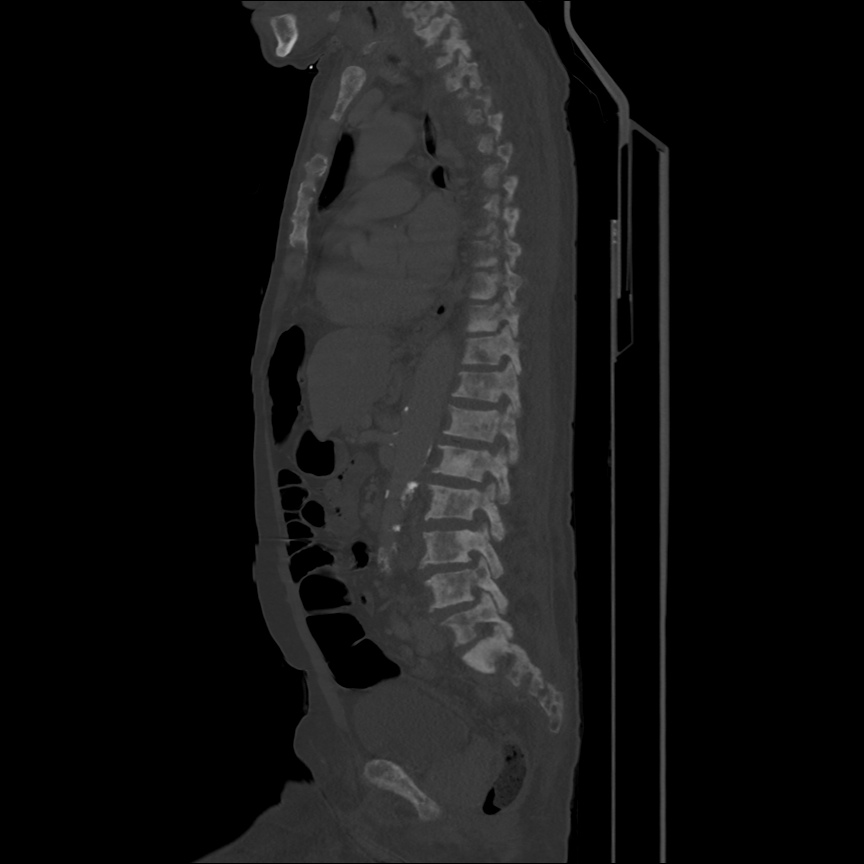

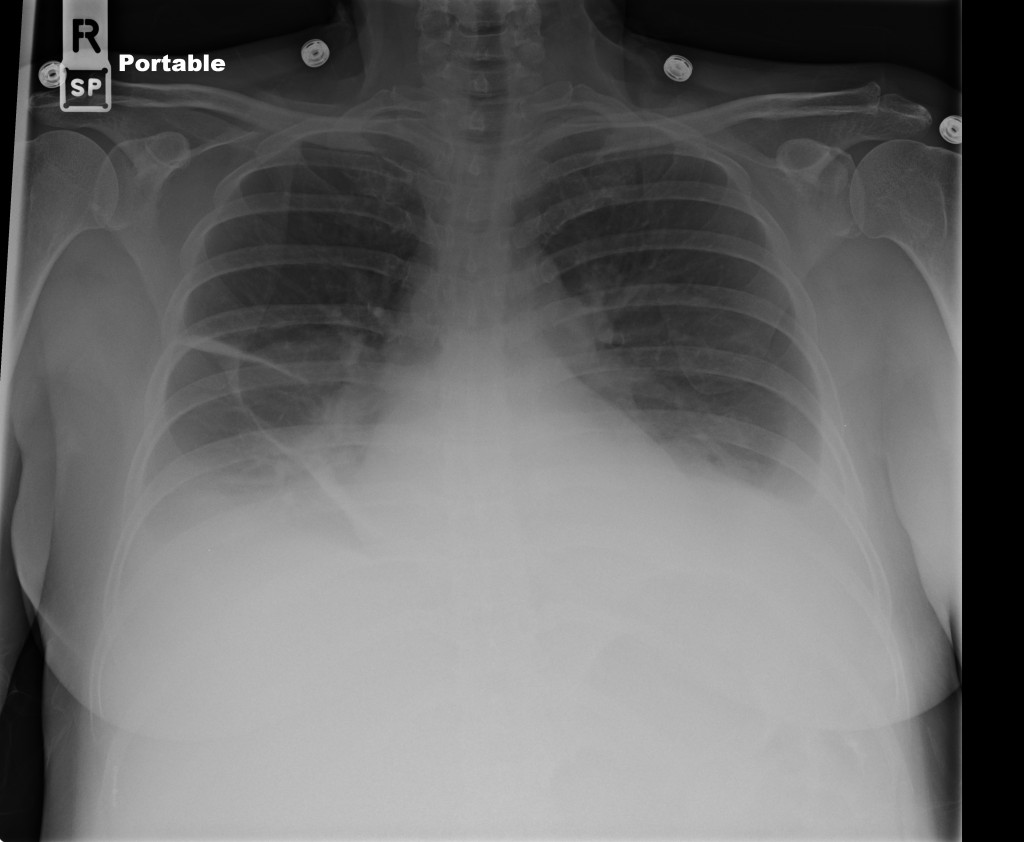

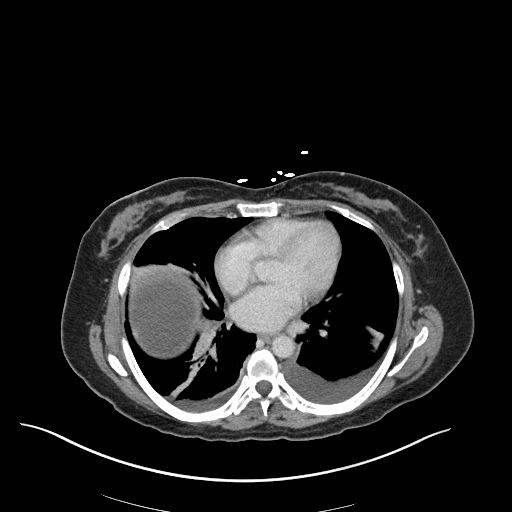

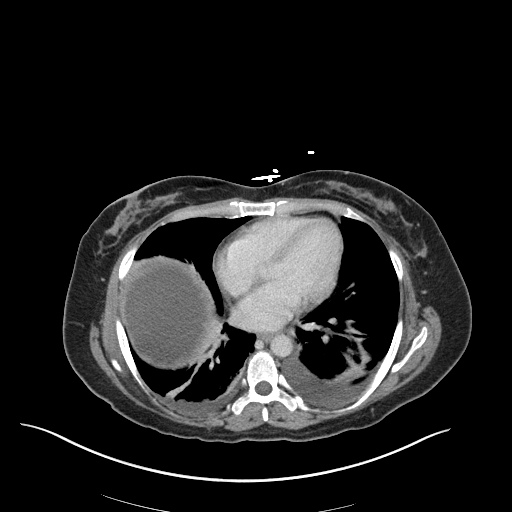

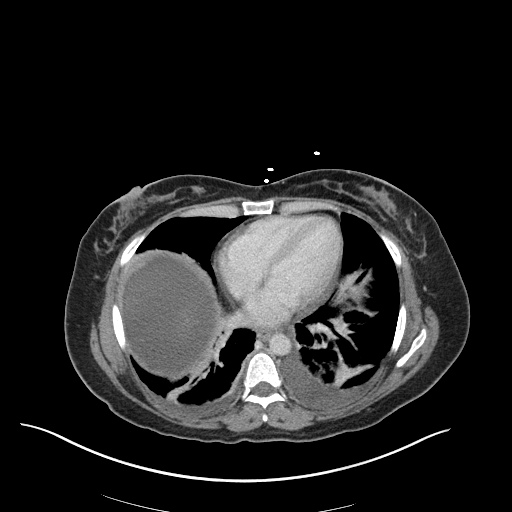

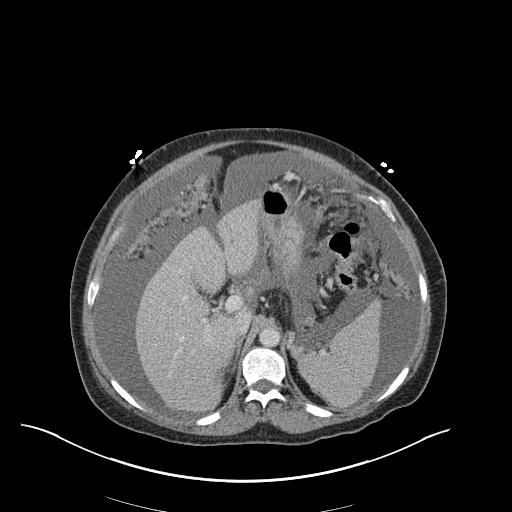

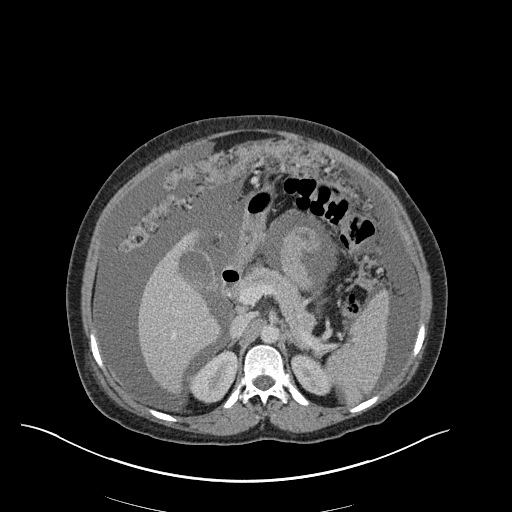

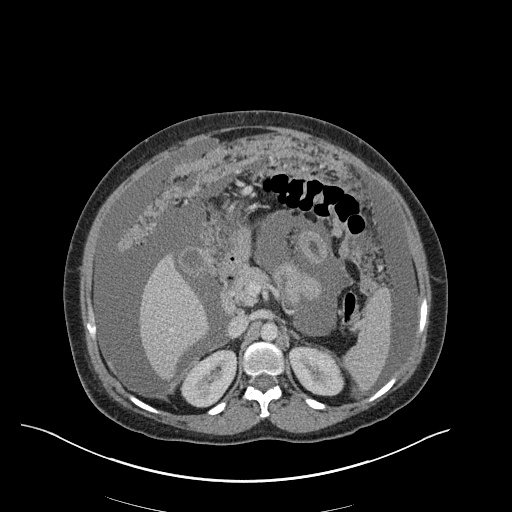

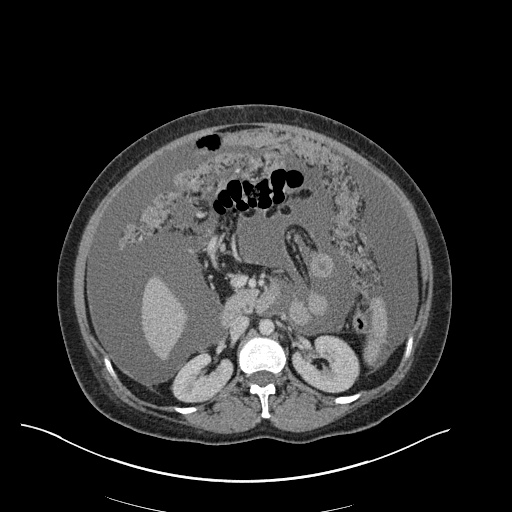

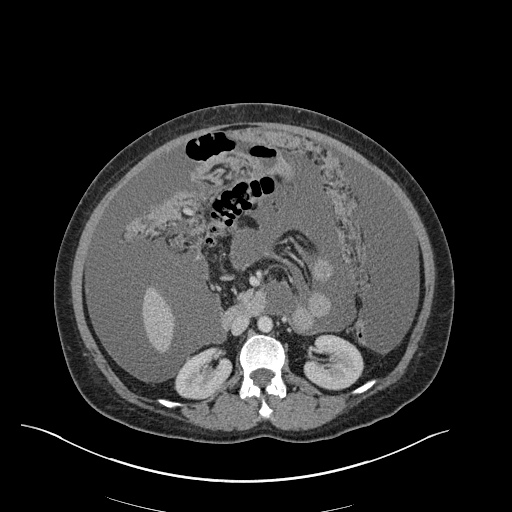

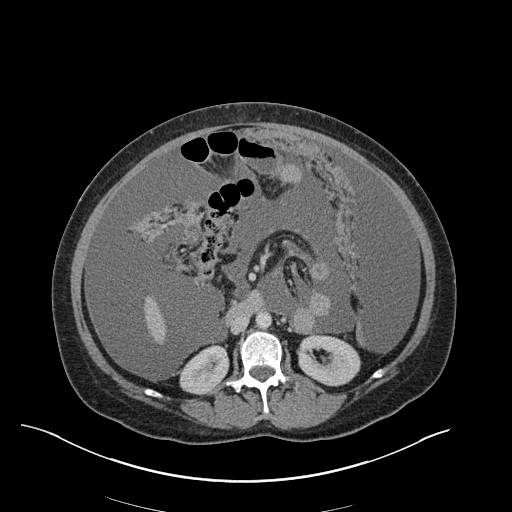

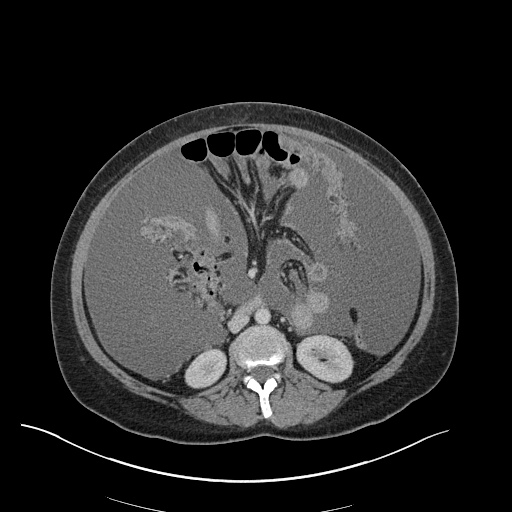

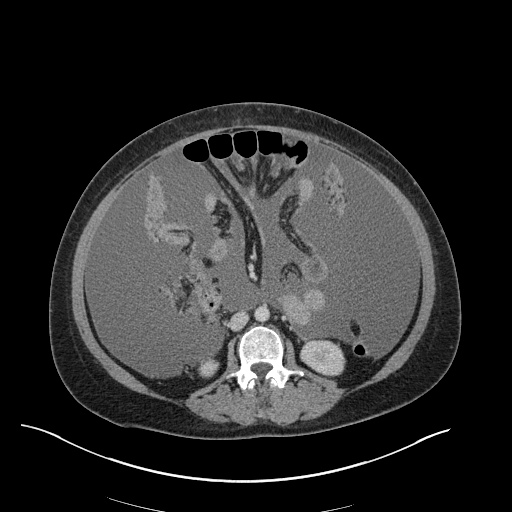

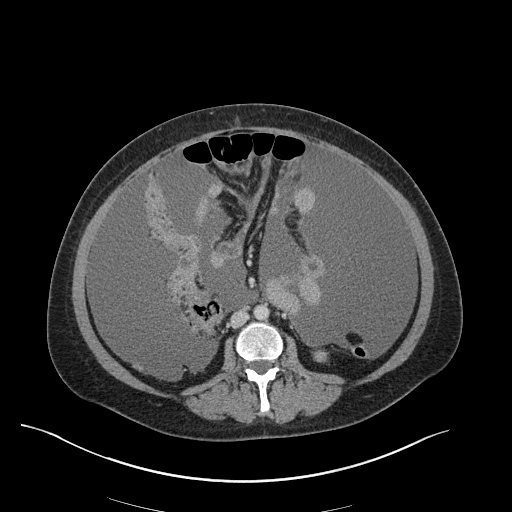

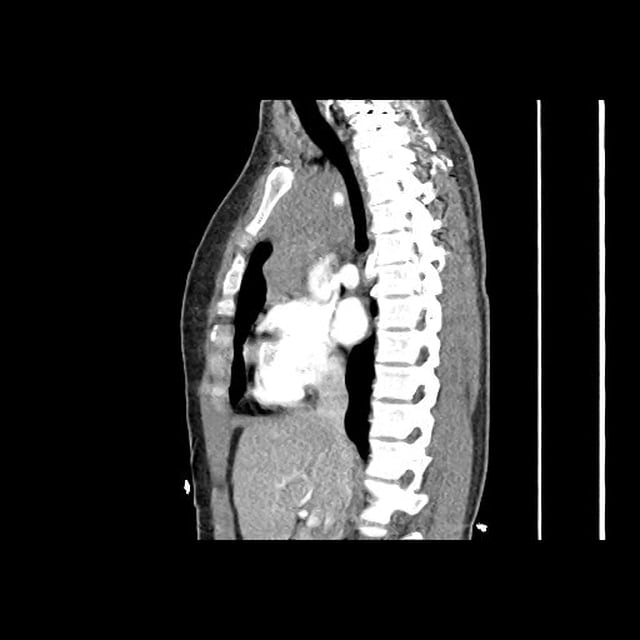

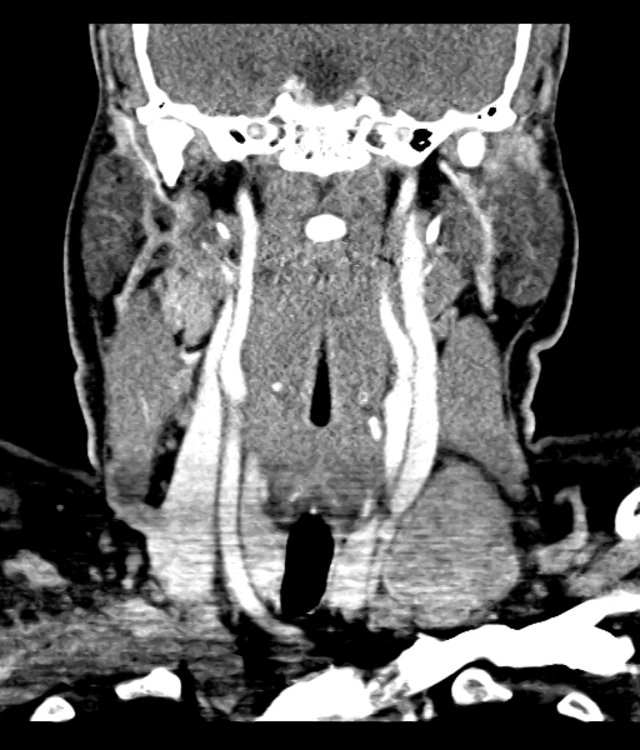

CT Pulmonary Angiography

Peribronchial opacities and patchy consolidation in the lungs which may represent multifocal pneumonia and/or aspiration in the appropriate clinical setting.

Mildly dilated main pulmonary artery suggestive of pulmonary arterial hypertension.

ED Course:

The patient was admitted to the medical intensive care unit for cardiopulmonary arrest presumed secondary to hypoxia and septic shock from healthcare-associated pneumonia or aspiration. The markedly elevated white blood cell count was attributed to a combination of infection and tissue ischemia from transient global hypoperfusion.

Definition: 1

- Markedly elevated leukocyte (particularly neutrophil) count without hematologic malignancy

- Cutoff is variable, 25-50k

Review of Available Literature

- Retrospective review of 135 patients with WBC >25k 2

- 48% infection

- 15% malignancy

- 9% hemorrhage

- 12% glucocorticoid or granulocyte colony stimulating therapy

- Retrospective review of 173 patients with WBC >30k 3

- 48% infection (7% C. difficile)

- 28% tissue ischemia

- 7% obstetric process (vaginal or cesarean delivery)

- 5% malignancy

- Observational study of 54 patients with WBC >25k 4

- Consecutive patients presenting to the emergency department

- Compared to age-matched controls with moderate leukocytosis (12-24k)

- Patients with leukemoid reaction were more likely to have an infection, be hospitalized and die.

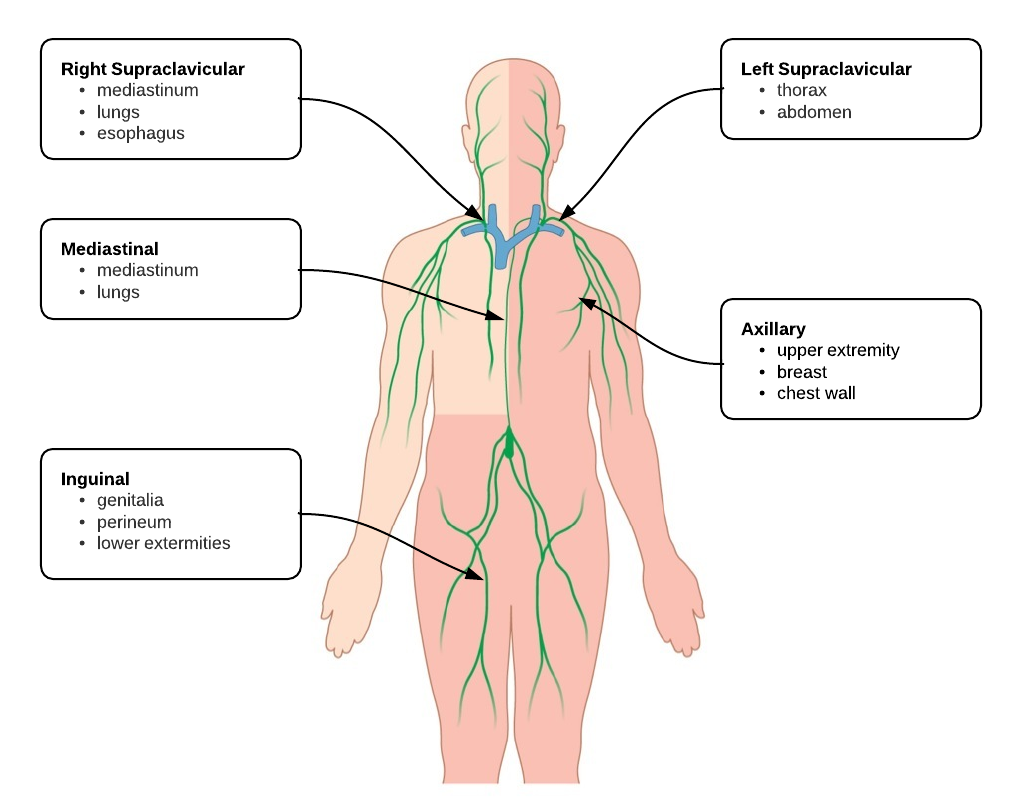

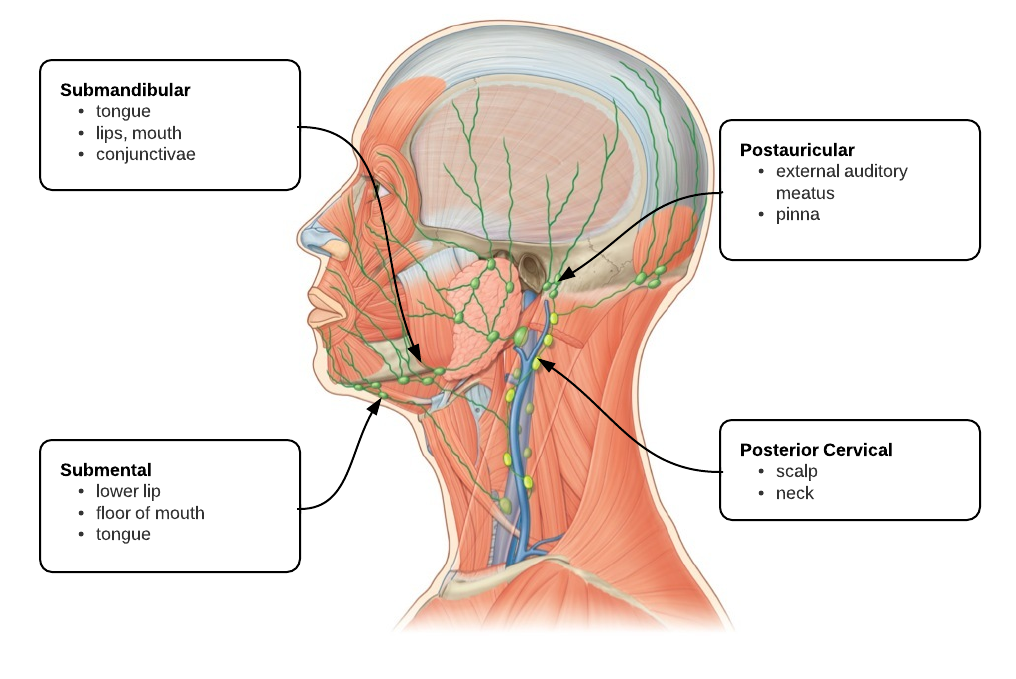

Differential Diagnosis of Leukemoid Reaction 1,5-8

References

- Sakka V, Tsiodras S, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Giamarellou H. An update on the etiology and diagnostic evaluation of a leukemoid reaction. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17(6):394-398. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2006.04.004.

- Reding MT, Hibbs JR, Morrison VA, Swaim WR, Filice GA. Diagnosis and outcome of 100 consecutive patients with extreme granulocytic leukocytosis. Am J Med. 1998;104(1):12-16.

- Potasman I, Grupper M. Leukemoid reaction: spectrum and prognosis of 173 adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(11):e177-e181. doi:10.1093/cid/cit562.

- Lawrence YR, Raveh D, Rudensky B, Munter G. Extreme leukocytosis in the emergency department. QJM. 2007;100(4):217-223. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcm006.

- Marinella MA, Burdette SD, Bedimo R, Markert RJ. Leukemoid reactions complicating colitis due to Clostridium difficile. South Med J. 2004;97(10):959-963. doi:10.1097/01.SMJ.0000054537.20978.D4.

- Okun DB, Tanaka KR. Profound leukemoid reaction in cytomegalovirus mononucleosis. JAMA. 1978;240(17):1888-1889.

- Halkes CJM, Dijstelbloem HM, Eelkman Rooda SJ, Kramer MHH. Extreme leucocytosis: not always leukaemia. Neth J Med. 2007;65(7):248-251.

- Granger JM, Kontoyiannis DP. Etiology and outcome of extreme leukocytosis in 758 nonhematologic cancer patients: a retrospective, single-institution study. Cancer. 2009;115(17):3919-3923. doi:10.1002/cncr.24480.