Brief History and Physical:

A young female with a history of schizophrenia presents to the emergency department reporting hallucinations. She had been diagnosed with schizophrenia one year previously and was briefly admitted to a psychiatric hospital. She discontinued her anti-psychotic (risperidone) two months ago, and over the past week she reports increasingly prominent auditory and visual hallucinations.

She denies recent illness, vomiting/diarrhea, changes in urinary habits, new medications, alcohol or illicit substance use. She also denies chest pain, palpitations or shortness of breath.

Vital signs are notable for a heart rate of 148bpm and are otherwise normal (including core temperature). Detailed physical examination is normal except for a rapid, regular heart rate. Mental status examination demonstrated normal level of alertness and orientation, linear and cogent responses and occasional response to internal stimuli during which she appeared anxious.

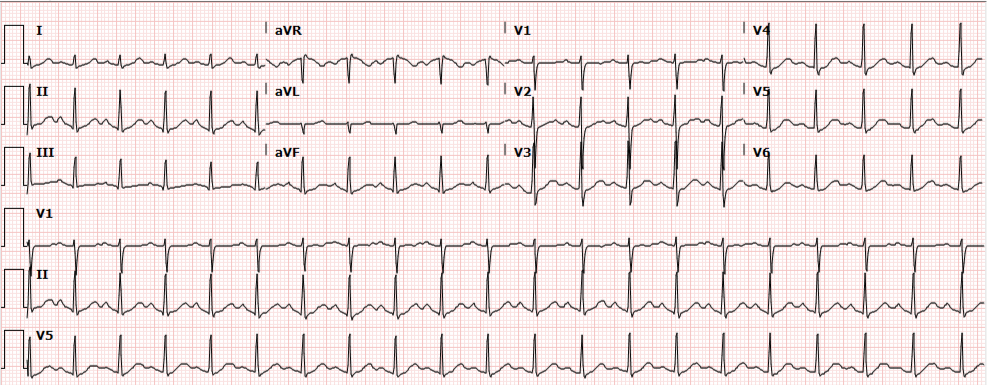

Initial evaluation and management included a 12-lead ECG which showed sinus tachycardia. Multiple boluses of normal saline were initiated while awaiting laboratory workup.

Update:

Laboratory studies were reviewed and unremarkable. Normal hemoglobin, normal chemistry panel, negative hCG, and negative toxicology screen. The patient remained persistently tachycardic with a heart rate ranging from 140-160bpm (again sinus tachycardia on 12-lead ECG). An atypical antipsychotic and anxiolytic were administered and additional studies were obtained. Serum TSH, troponin and D-dimer were normal and bedside ultrasound did not identify a pericardial effusion. The patient remained asymptomatic, reporting subjective improvement in anxiety and hallucinations. Psychiatry was consulted and the patient was placed in observation for monitoring of sinus tachycardia. Observation course was uneventful as the patient remained asymptomatic. Transthoracic echocardiography was normal. Psychiatry consultation recommended resumption of home anti-psychotic and outpatient follow-up. Tachycardia had improved but not resolved at the time of discharge (heart rate 109bpm) and the patient was instructed to follow-up with her primary care provider.

Algorithm for the Evaluation of Sinus Tachycardia

Any vital sign derangement is concerning and tachycardia may be associated with unanticipated death after discharge home1. The presence of tachycardia suggests one of several categories of hemodynamic, autonomic, or endocrine/metabolic derangement.

Demand for increased cardiac output

A perceived demand for increased cardiac output will prompt chronotropic (and inotropic) amplification before hypotension develops. Causative etiologies include: volume depletion (from hemorrhage, gastrointestinal or renal losses), distributive processes (such as infection), obstruction (pulmonary embolus, or pericardial effusion with impending tamponade), or tissue hypoxia (anemia or lung disease).

Autonomic nervous system

Autonomic nervous system disturbances induced by stimulant, sympathomimetic or anti-cholinergic use, or withdrawal of certain agents such as ethanol or beta-blockers may be at fault.

Endocrine and other causes

Hyperthyroidism and pheochromocytoma should be considered, and as diagnoses of exclusion: anxiety, pain, or inappropriate sinus tachycardia2.

- Evaluation:

- Core temperature

- CBC

- Troponin

- D-dimer

- Bedside cardiac ultrasound

- Urine toxicology screen

- Ethanol level

- TSH/T4

Algorithm for the Evaluation of Narrow-Complex Tachycardia3,4,5,6

References:

- Sklar DP, Crandall CS, Loeliger E, Edmunds K, Paul I, Helitzer DL. Unanticipated Death After Discharge Home From the Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(6):735-745. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.11.018.

- Olshansky B, Sullivan RM. Inappropriate sinus tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(8):793-801. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.074.

- Yusuf S, Camm AJ. Deciphering the sinus tachycardias. Clin Cardiol. 2005;28(6):267-276.

- Katritsis DG, Josephson ME. Differential diagnosis of regular, narrow-QRS tachycardias. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12(7):1667-1676. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.046.

- Bibas L, Levi M, Essebag V. Diagnosis and management of supraventricular tachycardias. CMAJ. 2016;188(17-18):E466-E473. doi:10.1503/cmaj.160079.

- Link MS. Clinical practice. Evaluation and initial treatment of supraventricular tachycardia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(15):1438-1448. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1111259.