HPI:

HPI:

1yo M, ex-term, previously healthy, with 8d tactile fever/diarrhea, initially watery, presenting now due to bloody diarrhea x1d. Mother reports 8-10 episodes/day, decreased PO intake and urine output x4d and changes in behavior (lethargy, irritability). No vomiting, no e/o abdominal pain, no cough, no seizures, no weight loss, no known sick contacts.

PMH:

- Full term

- No perinatal complications

- Vaccination history unknown

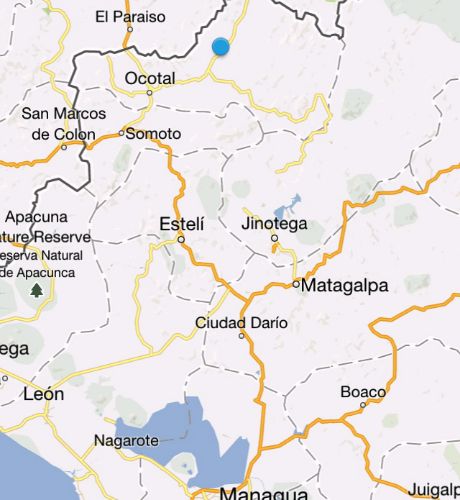

SHx:

- Meeting all developmental milestones

- No sick contacts

PSH/FH/Meds/Allergies:

None

Physical Exam:

- VS: HR 135 BP 86/60 RR 24 T N/A Wt 11kg (60%)

- General: Patient was initially examined after initial rehydration with IVF. Well-appearing child, interactive and smiling.

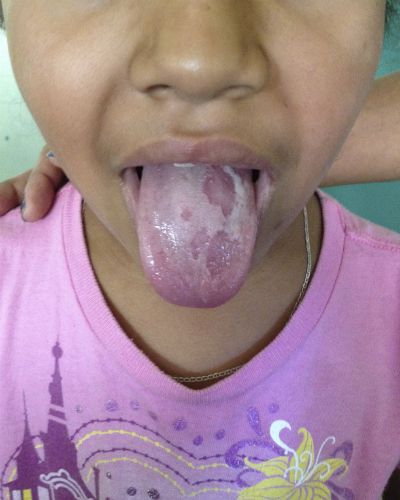

- HEENT: NC/AT, PERRL, MMM no lesions, no nuchal rigidity

- CV: RRR, normal S1/S2

- Lungs: CTAB

- Abd: +BS, soft, NT/ND, no rebound/guarding

- Ext: Warm, well-perfused, 2+ peripheral pulses (radial, DP, PT), capillary refill <2s

- Skin: No visible skin lesions

- Neuro: Alert and responsive

Assessment/Plan:

1yo healthy male with fever, bloody diarrhea and history consistent with dehydration. Most likely cause of acute diarrhea in this patient is infectious, particularly Shigella spp given presence of blood. Other concerning causes of diarrhea in this patient with reports of fever and changes in mental status include a serious bacterial illness (meningitis, pneumonia, UTI), however, these are less likely given the predominant, voluminous diarrhea and absence of symptoms associated with each. Other considerations include appendicitis, volvulus, intussusception, however again copious diarrhea in association with a benign abdominal exam makes these causes less likely. Early presentation of chronic diarrhea cannot be ruled out, however unlikely given association with fever and local prevalence of infectious causes.

Management included IV rehydration, followed by maintenance with PO ORS, early nutritional support, and ciprofloxacin 15mg/kg IV q12h.

Types and causes of acute diarrhea: 1, 2

Assessment of Hydration Status

| | Dehydration Level |

| Variable/Sign | Mild (3-5%) | Moderate (6-9%) | Severe (>10%) |

| General appearance | Restless, alert | Drowsy, postural hypotension | Limp, cold, sweaty, cyanotic extremities |

| Radial pulse | Normal rate, strength | Rapid, weak | Rapid, thready, sometimes impalpable |

| Respiration* | Normal | Deep | Deep and rapid |

| Anterior fontanelle | Normal | Sunken | Very sunken |

| SBP | Normal | Normal or low | Low |

| Capillary refill* | Normal (<2s) | Prolonged (2-4s) | Markedly prolonged (>4s) |

| Skin turgor* | Normal | Pinch retracts slowly | Pinch retracts very slowly |

| Eyes | Normal | Sunken | Grossly sunken |

| Tears | Present | Absent | Absent |

| Mucous membranes | Moist | Dry | Very Dry |

* = sensitivity > 70% 3,4

Management of Acute Diarrhea: 5,6

Pathogens causing diarrhea: 6

| Pathogen | Epidemiology/Transmission | Comments | Incubation | Fever | Abd. pain | N/V | Bloody stool | Stool WBC | Stool Heme |

| S. aureus, B. cereus | Food poisoning with preformed toxin | Vomiting > diarrhea | 1-6h | X | – | ✓ | X | X | X |

| C. perfringens | Spores germinate in meats, poultry | | 6-24h | X | – | ✓ | X | X | X |

| Norovirus | Winter outbreaks in schools, nursing homes, cruise ships | Adults: diarrhea Children: vomiting | 1-2d | – | ✓ | – | X | X | X |

| Rotavirus | #1 MCC children | Vaccine available | 1-2d | – | ✓ | – | X | X | X |

| Campylobacter | #1 MCC invasive enterocolitis in US Undercooked poultry | GBS | 2-5d | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | – |

| Salmonella | #2 MCC enterocolitis in US Outbreaks Undercooked egg, dairy, poultry | | 1-3d | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | – |

| Shigella | Community-acquired, person-to-person | | 1-3d | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – |

| EIEC | Outbreaks Undercooked beef, raw seed sprouts | Produces Shiga toxin | 1-8d | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| C. difficile | Nosocomial | Leukocytosis | | – | – | X | – | ✓ | – |

| E. histolytica | Travel to tropical regions | | | – | – | – | – | – | ✓ |

| Giardia | Day care, waterborne transmission | | 1-3d | X | ✓ | – | X | X | X |

| Vibrio | Contaminated water, seafood | | 1-3d | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yersinia | Foodborne transmission | Mesenteric lympadenitis (simulates acute appendicitis) | 1-3d | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

References:

- Huilan, S., Zhen, L. G., Mathan, M. M., Mathew, M. M., Olarte, J., Espejo, R., Khin Maung, U., et al. (1991). Etiology of acute diarrhoea among children in developing countries: a multicentre study in five countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 69(5), 549–555.

- Navaneethan, U., & Giannella, R. A. (2008). Mechanisms of infectious diarrhea. Nature clinical practice. Gastroenterology & hepatology, 5(11), 637–647. doi:10.1038/ncpgasthep1264

- Steiner, M. J., DeWalt, D. A., & Byerley, J. S. (2004). Is this child dehydrated? JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association, 291(22), 2746–2754. doi:10.1001/jama.291.22.2746

- Gorelick, M. H., Shaw, K. N., & Murphy, K. O. (1997). Validity and reliability of clinical signs in the diagnosis of dehydration in children. Pediatrics, 99(5), E6.

- Harris, JB, Pietroni M. Approach to the child with acute diarrhea in developing countries. In: UpToDate, Basow, DS (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2013.

- Thielman, N. M., & Guerrant, R. L. (2004). Clinical practice. Acute infectious diarrhea. The New England journal of medicine, 350(1), 38–47. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp031534