CC:

Macroscopic hematuria

HPI:

85yo male with a history of prostate cancer s/p radiation and androgen deprivation therapy four years ago complicated by urethral strictures requiring chronic indwelling catheter who presented to the ED yesterday with 3 days of red urine followed by no output from catheter and abdominal pain. In the ED, the patient was found to have stable hemoglobin and creatinine and was discharged with urology follow-up after symptom resolution with catheter irrigation.

Today, the patient reports no new issues, denies abdominal/flank pain, further catheter obstruction, fevers/chills. He states that his urine has been light pink in color, without clots, and significantly more clear than the prior 3 days. He has had intermittent episodes of blood in his urine in the past, but never causing obstruction. His catheter is managed at home with regular (q3wk) changes and no recent traumatic catheterizations.

He denies any new back/bone pain or unintentional weight loss.

PMH:

|

PSH:

|

FH:

|

SHx:

|

Meds:

|

Allergies:

|

Physical Exam:

| VS: | T | 98.4 | HR | 64 | RR | 13 | BP | 136/94 | O2 | 99% RA |

| Gen: | Well-appearing, pleasant man in no acute distress. | |||||||||

| Abd: | +BS, soft, NT/ND, no suprapubic tenderness, no CVAT | |||||||||

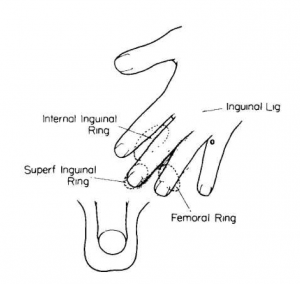

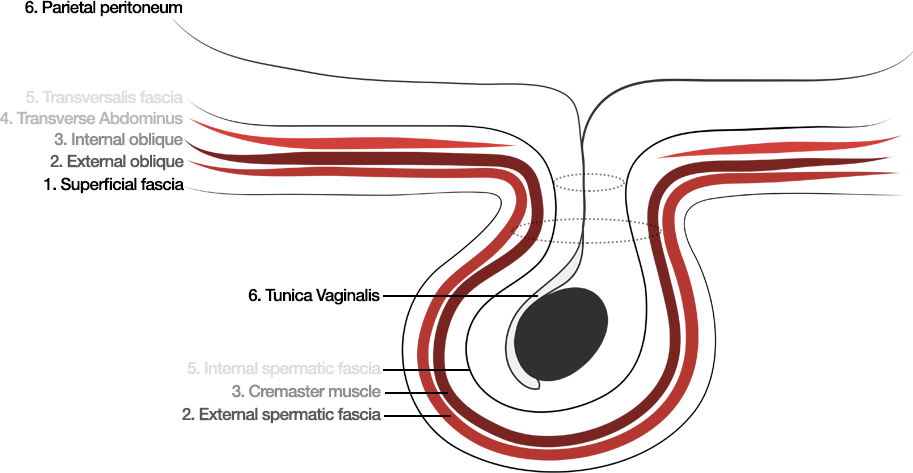

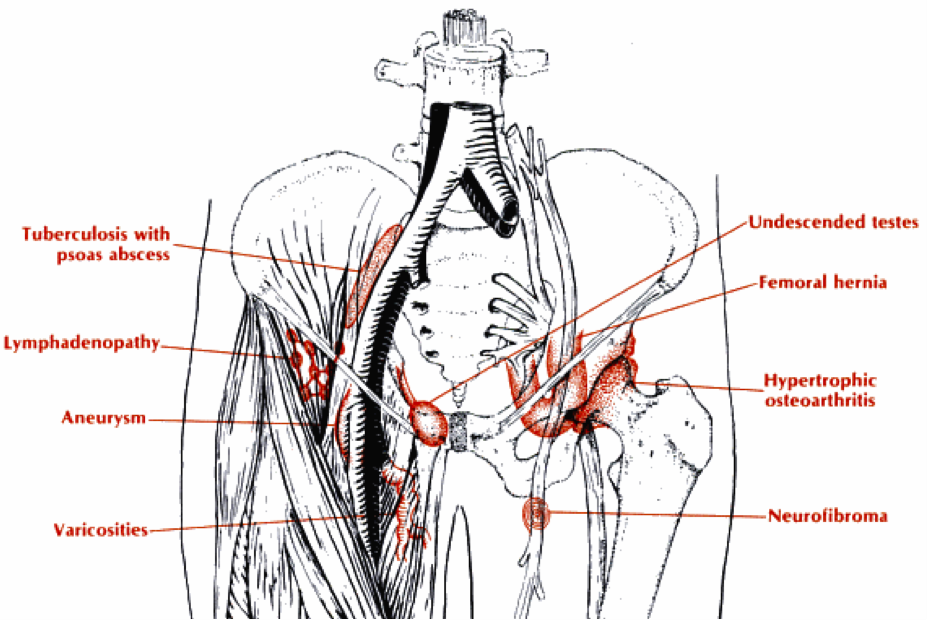

| GU: | Foley catheter in place draining clear-pink fluid to leg bag, no clots. No evidence of trauma to urethra, no visible skin lesions. Testes descended bilaterally, no inguinal lymphadenopathy. | |||||||||

Assessment/Plan:

85M hx CaP (2009) s/p radiation and androgen deprivation therapy with urethral strictures requiring chronic indwelling catheter presenting with macroscopic hematuria. Given patient’s history, radiation cystitis is a likely cause of his symptoms. However, given the long-standing catheter, other considerations include trauma and infection. Also, recurrence or new malignancy must be considered. Will obtain UA, UCx, and schedule patient for cystoscopy with bilateral retrograde pyelogram. Also, educated patient on how to irrigate catheter if needed and provided ED precautions should obstruction persist despite irrigation attempts. Patient’s last surveillance PSA undetectable, continue routine follow-up.

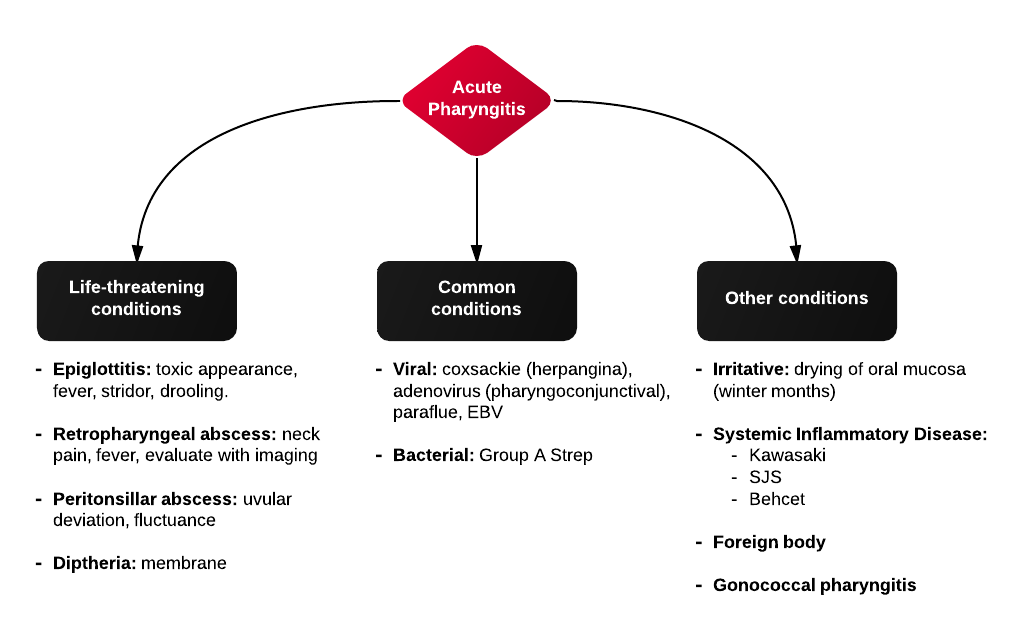

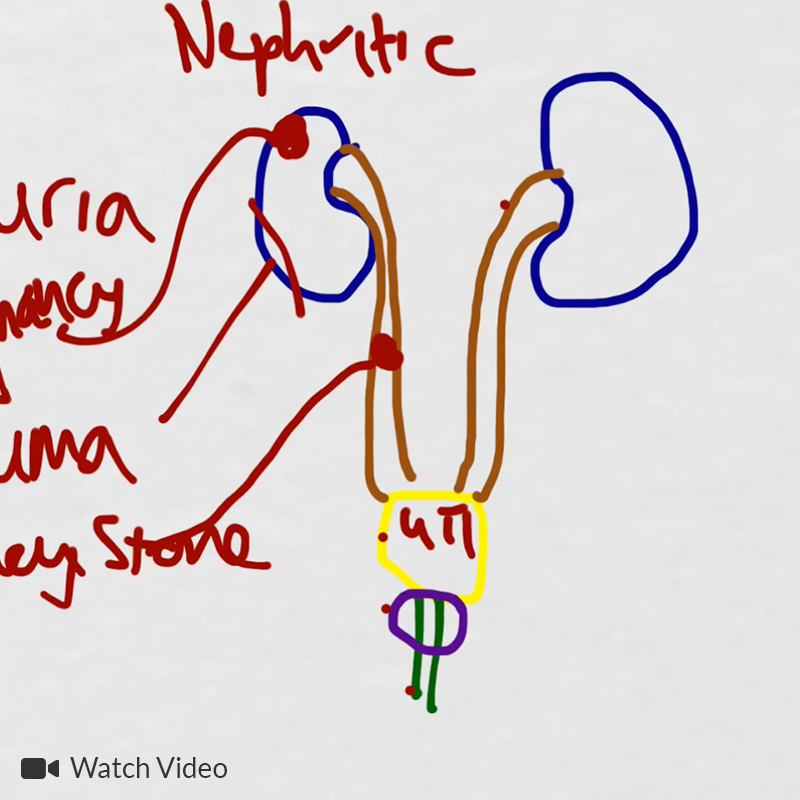

Differential Diagnosis of Macroscopic Hematuria

Important Historical Elements:

- Painless: suggests malignancy

- Painful: suggests calculi/infection

- Urinalysis: presence of dysmorphic RBC’s, RBC/WBC casts, proteinuria suggest intrinsic renal disease

- Timing: early (distal urethra), throughout (upper urinary tract), terminal (bladder neck, prostatic)

Guided Lecture

Watch “Gross Hematuria: Just a Bit of Kool-Aid” from EM Ed. In this lecture Dr. Basrai reviews the differential diagnosis and management of macroscopic hematuria in the emergency department.

References:

- Hicks, D., & Li, C.-Y. (2007). Management of macroscopic haematuria in the emergency department. Emergency medicine journal : EMJ, 24(6), 385–390. doi:10.1136/emj.2006.042457

- Mazhari, R., & Kimmel, P. L. (2002). Hematuria: an algorithmic approach to finding the cause. Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine, 69(11), 870–872–4– 876.

- Howes DS, Bogner MP. Chapter 94. Urinary Tract Infections and Hematuria. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Cline DM, Ma OJ, Cydulka RK, Meckler GD, eds.Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2011. http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=6362340. Accessed June 14, 2013.

- Sutton, J. M. (1990). Evaluation of hematuria in adults. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association, 263(18), 2475–2480.

CC:

CC:

HPI:

HPI:

ID:

ID: