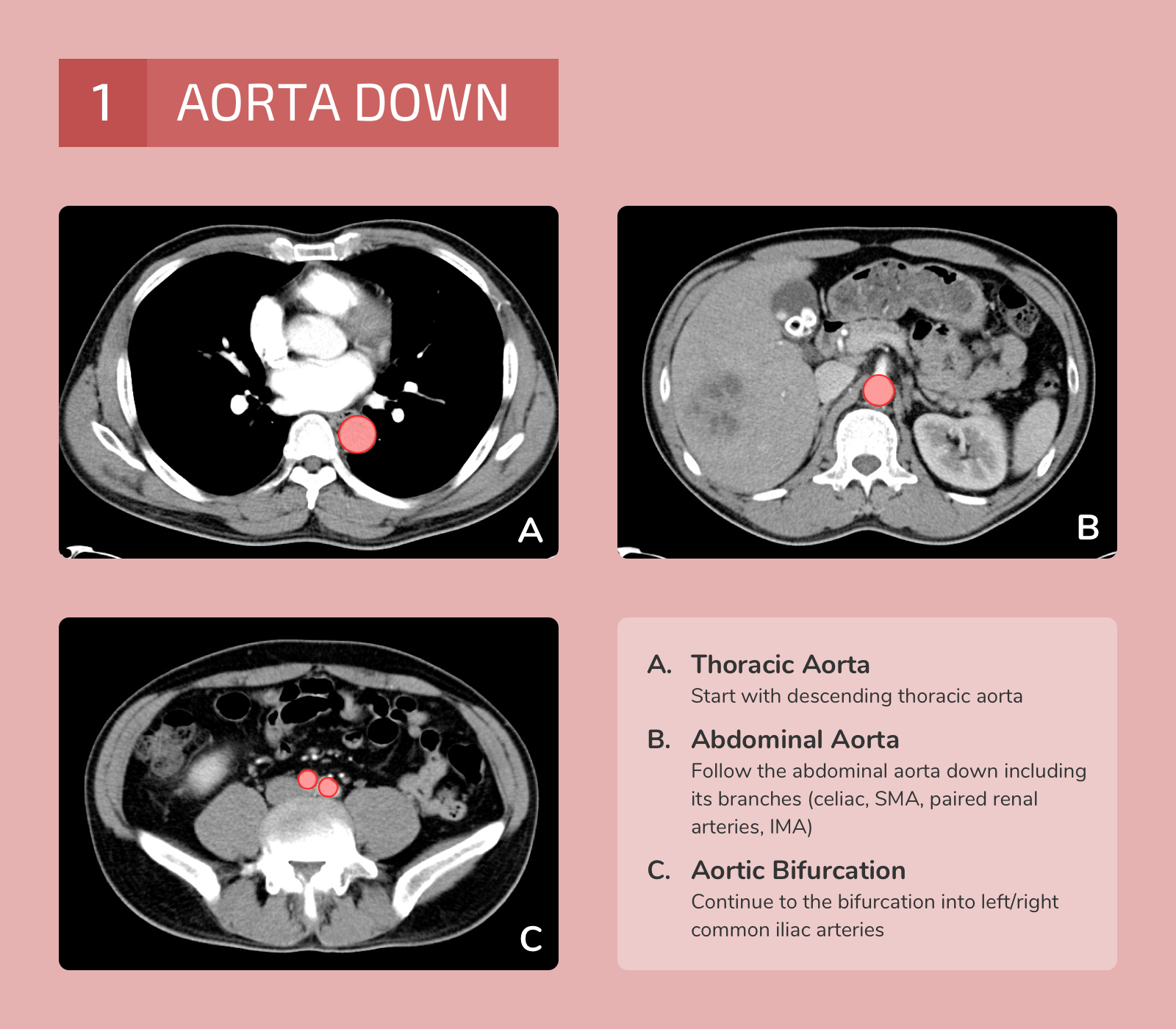

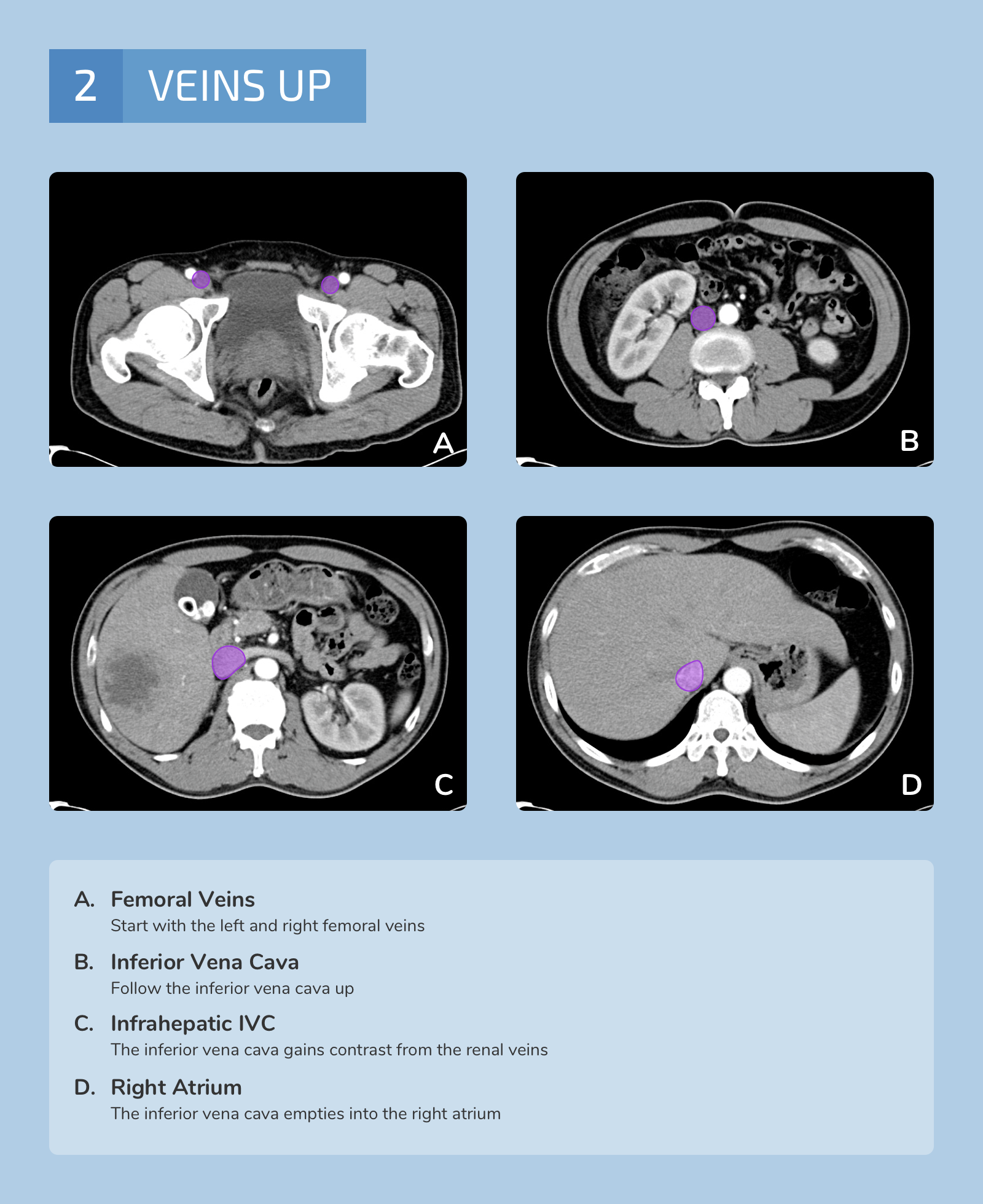

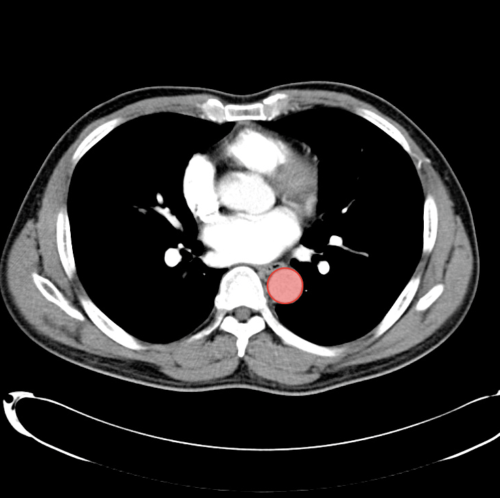

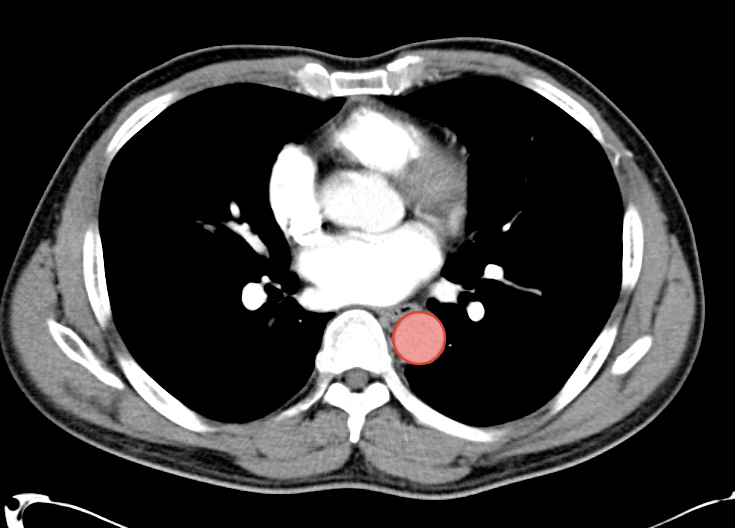

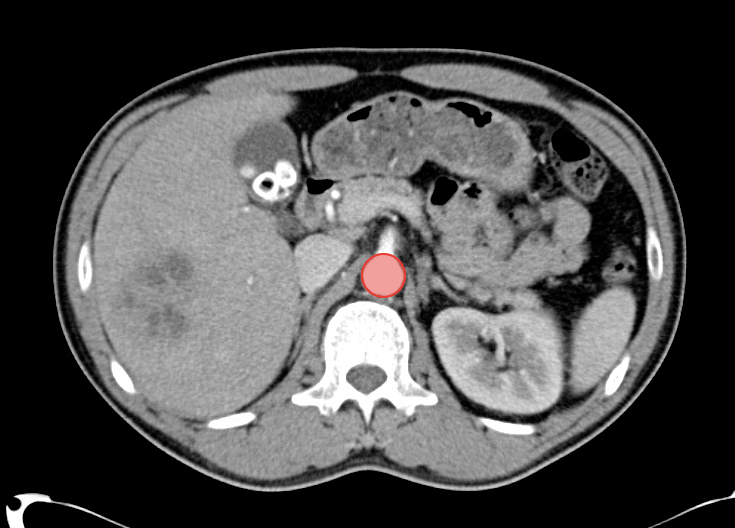

The emergency physician should be adept at the interpretation of computed tomography of the head, particularly for life-threatening processes where awaiting a radiologist interpretation may unnecessarily delay care.

As with the approach detailed previously for imaging of the abdomen and pelvis, a similar structured method for interpretation of head imaging exists and follows the mnemonic “Blood Can Be Very Bad”.

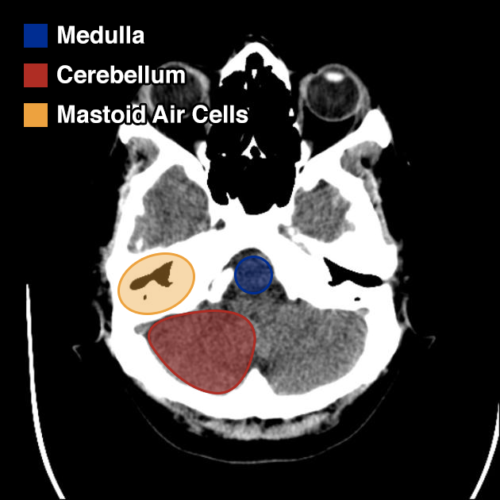

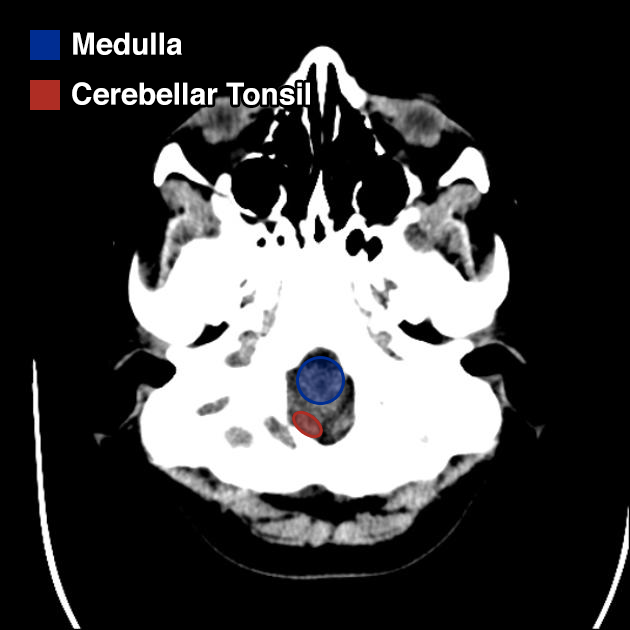

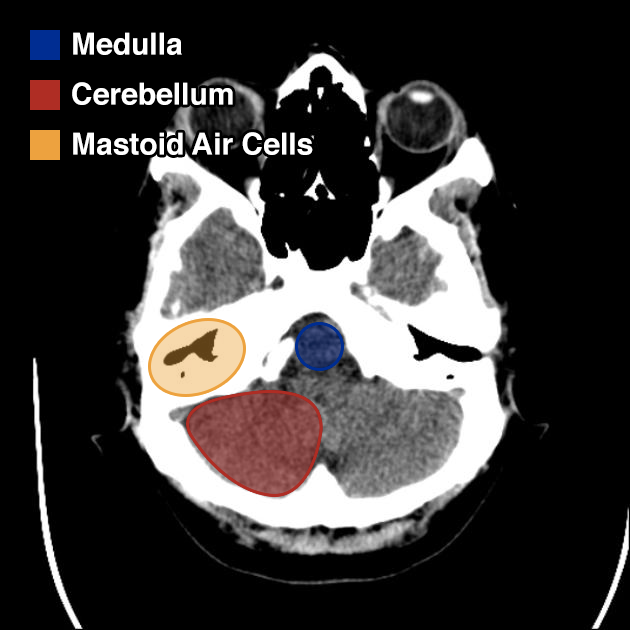

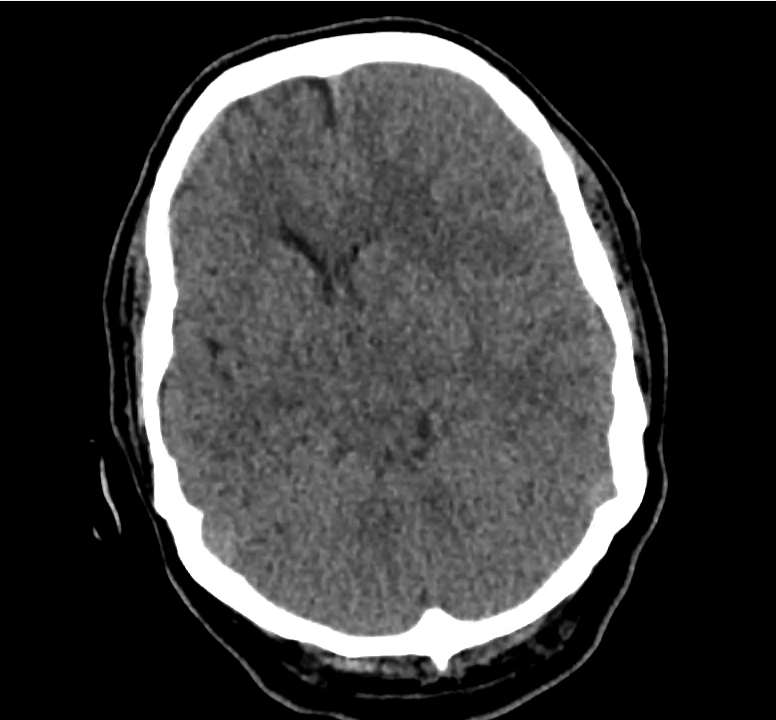

Normal Neuroanatomy

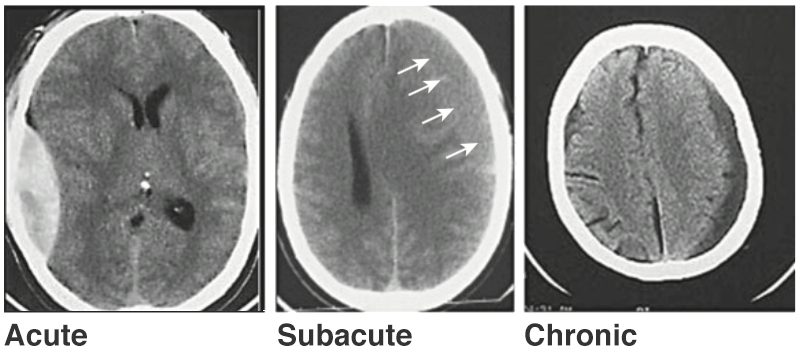

Blood: Blood

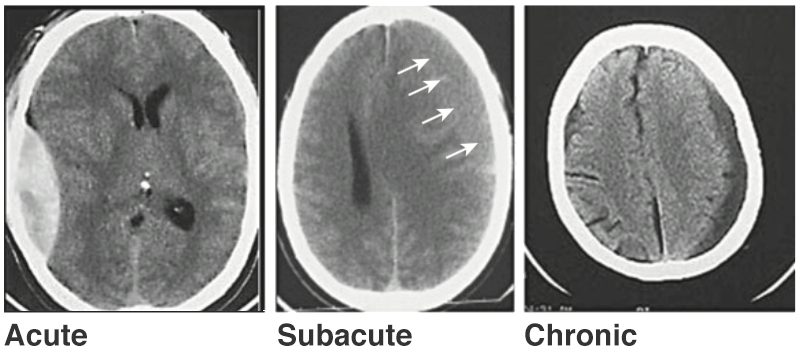

- Density

- Acute: hyperdense (50-100HU)

- 1-2wks: isodense with brain

- 2-3wks: hypodense with brain

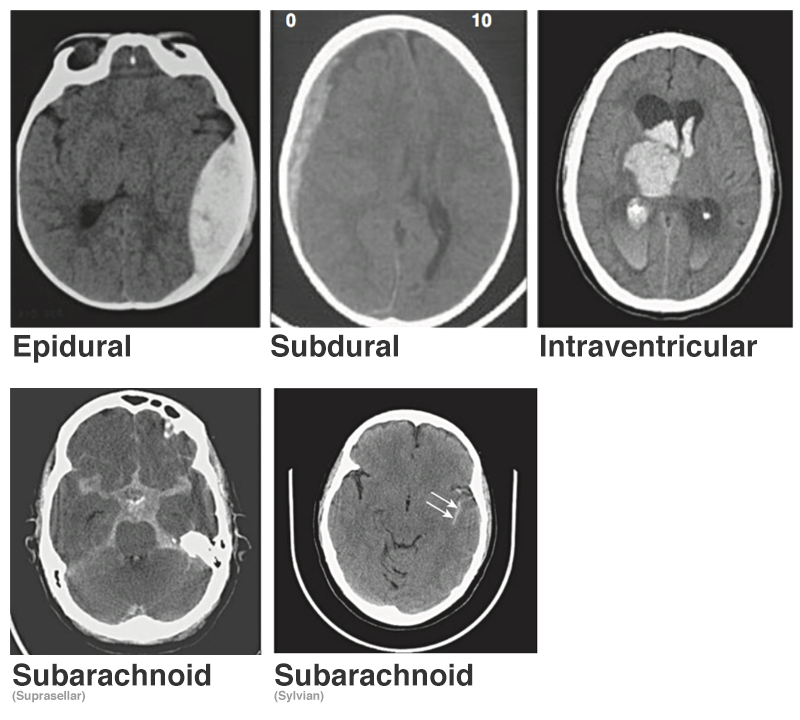

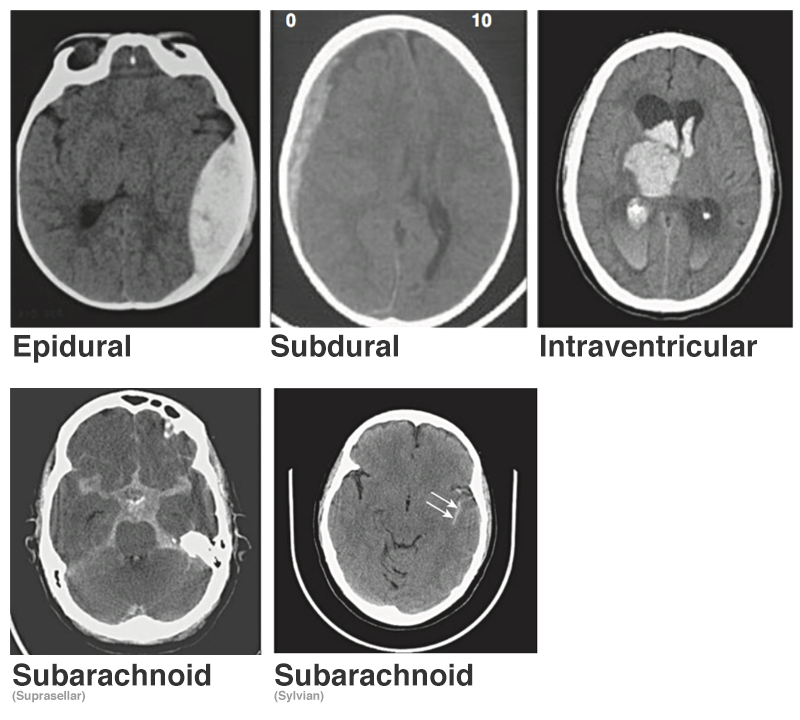

Types/Locations

- Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage/Contusions

- Sudden deceleration of the head causes the brain to impact on bony prominences (e.g., temporal, frontal, occipital poles).

- Non-traumatic hemorrhagic lesions seen more frequently in elderly and located in basal ganglia.

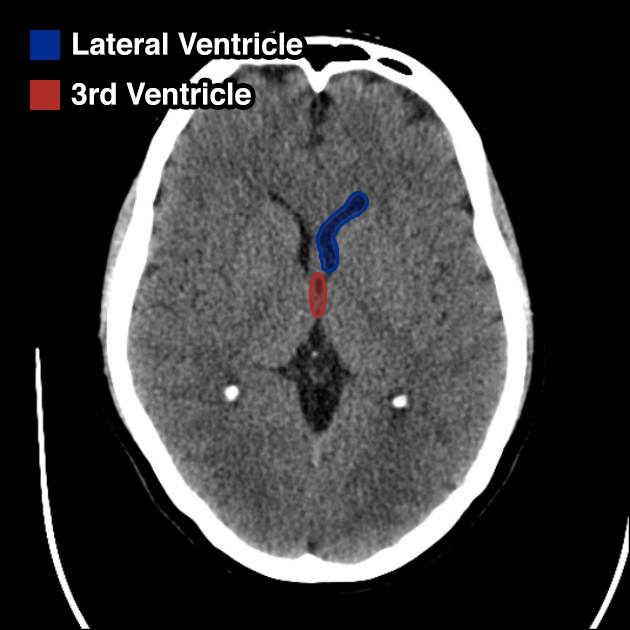

- Intraventricular Hemorrhage

- White density in otherwise black ventricular spaces, can lead to obstructive hydrocephalus and elevated ICP.

- Associated with worse prognosis in trauma.

- Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

- Hemorrhage into subarachnoid space usually filled with CSF (cistern, brain convexity).

- Extracranial Hemorrhage

- Presence of significant extracranial blood or soft-tissue swelling should point examiner to evaluation of underlying brain parenchyma, opposing brain parenchyma (for contrecoup injuries) and underlying bone for identification of fractures.

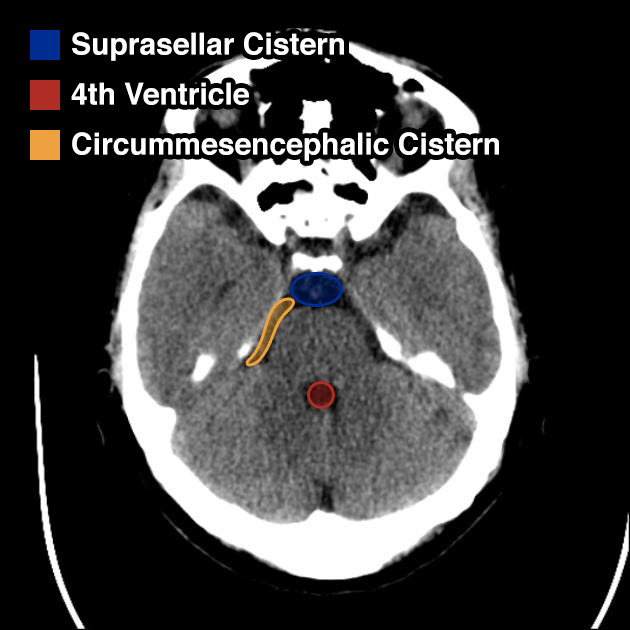

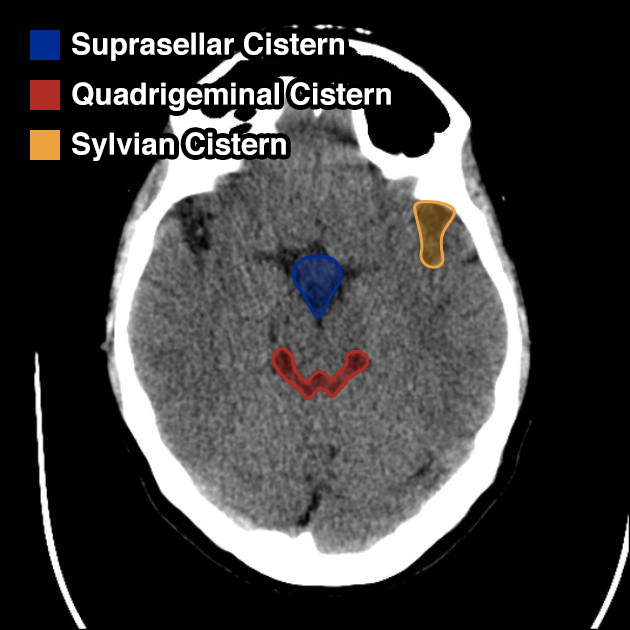

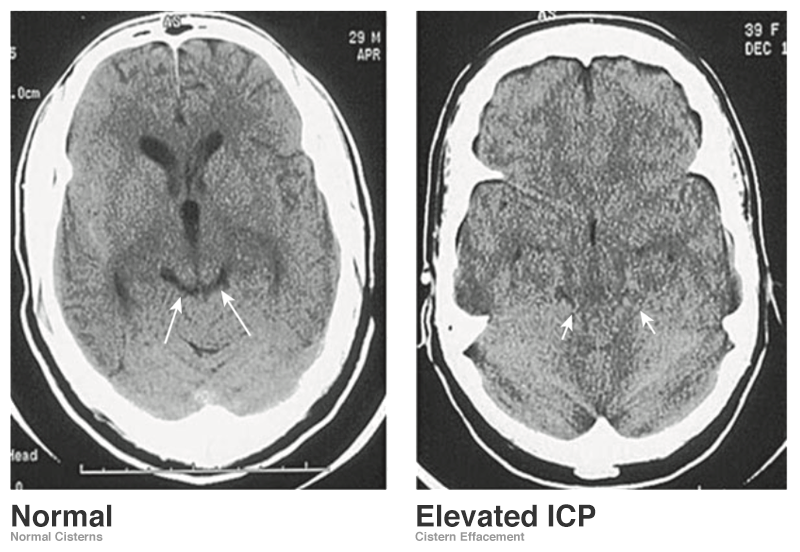

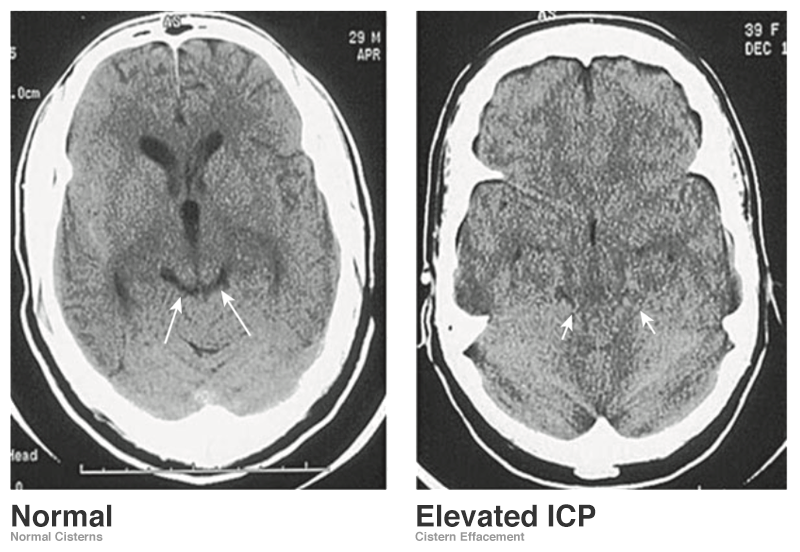

Can: Cisterns

Evaluating the cisterns is important for the identification of increased intracranial pressures (assessed by effacement of spaces) and presence of subarachnoid blood.

- Circummesencephalic: CSF ring around midbrain and most sensitive marker for elevated ICP

- Suprasellar: Star-shaped space above the sella

- Quadrigeminal: W-shaped space at the top of the midbrain

- Sylvian: Bilateral space between temporal/frontal lobes

Be: Brain

Evaluate the brain parenchyma, including an assessment of symmetry of the gyri/sulci pattern, midline shift, and a clear gray-white differentiation.

Very: Ventricles

Evaluate the ventricles for dilation or compression. Compare the ventricle size to the size of cisterns, large ventricles with normal/compressed cisterns and sulcal spaces suggests obstruction.

Bad: Bone

Switch to bone windows to evaluate for fracture. The identification of small, linear, non-depressed skull fractures may be difficult to identify as they are often confused with sutures – surrogates include pneumocephalus, and abnormal aeration of mastoid air cells and sinuses. The Presence of fractures increases the suspicion for intracranial injury, search adjacent and opposing parenchyma and extra-axial spaces.

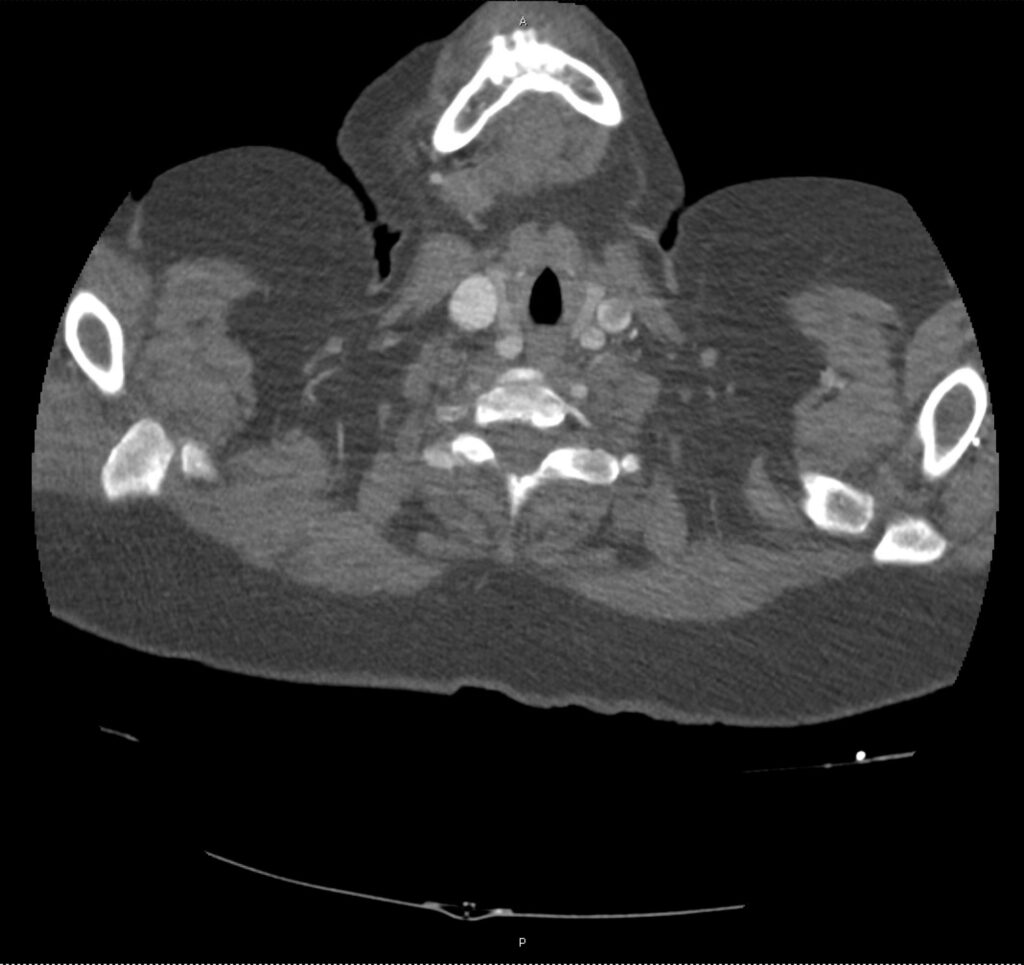

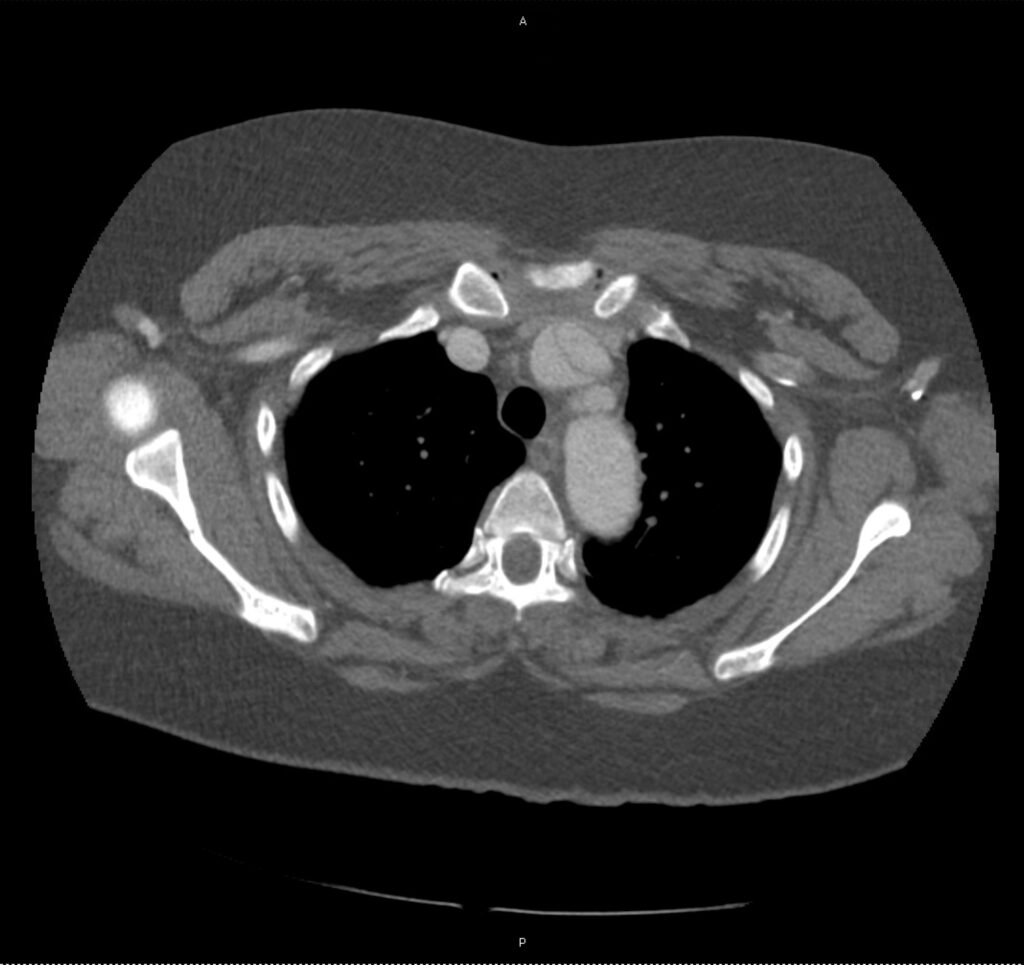

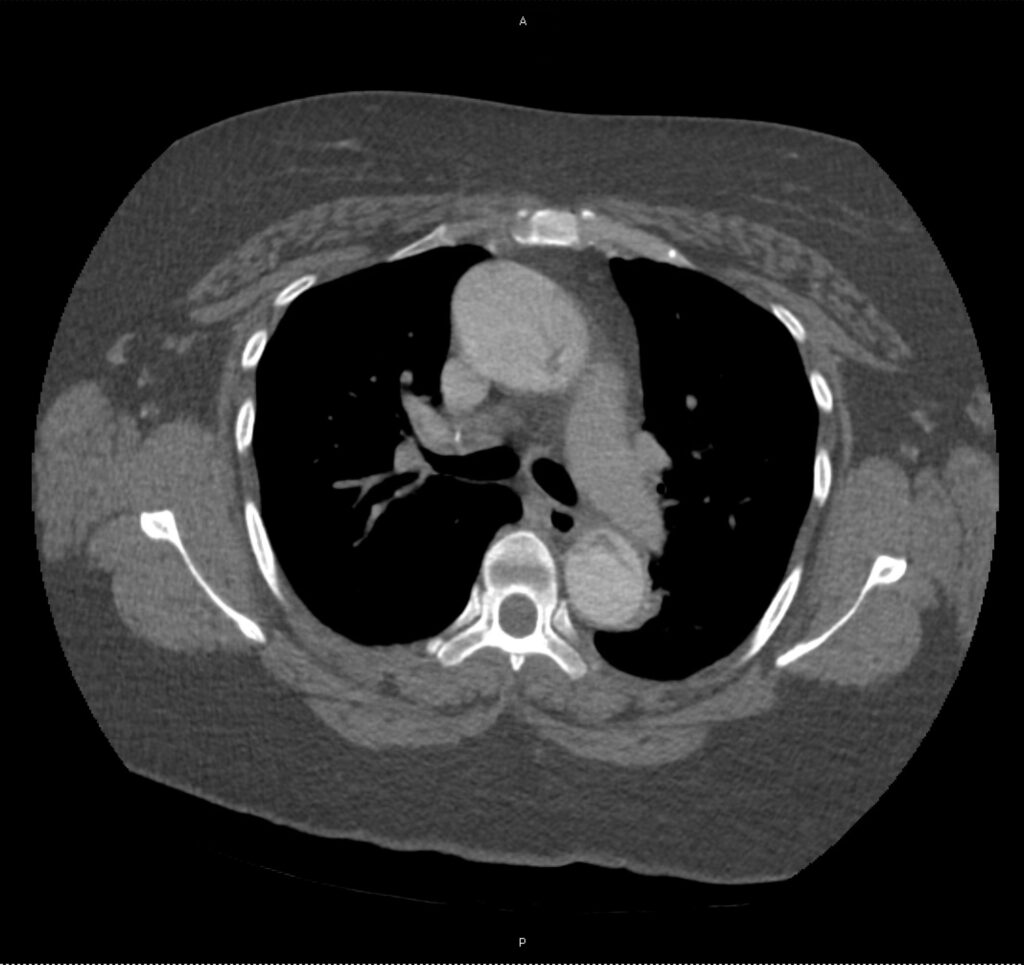

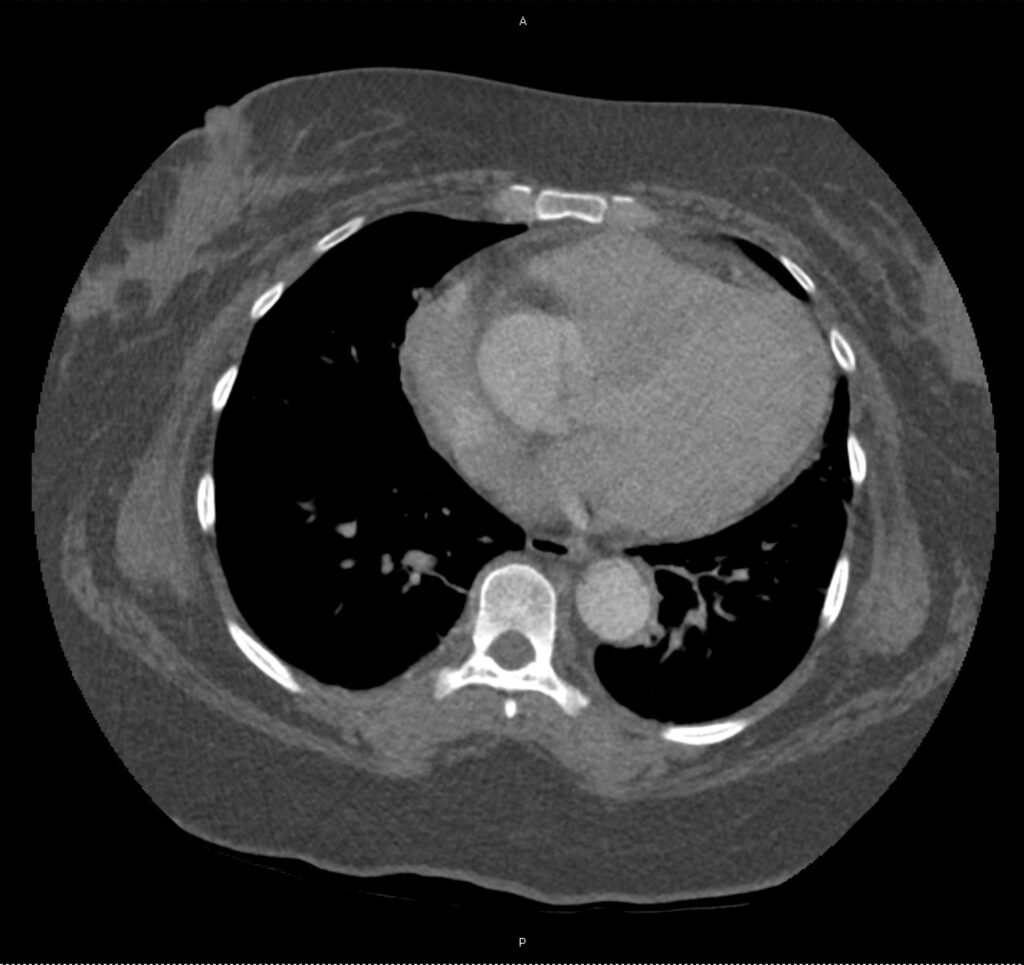

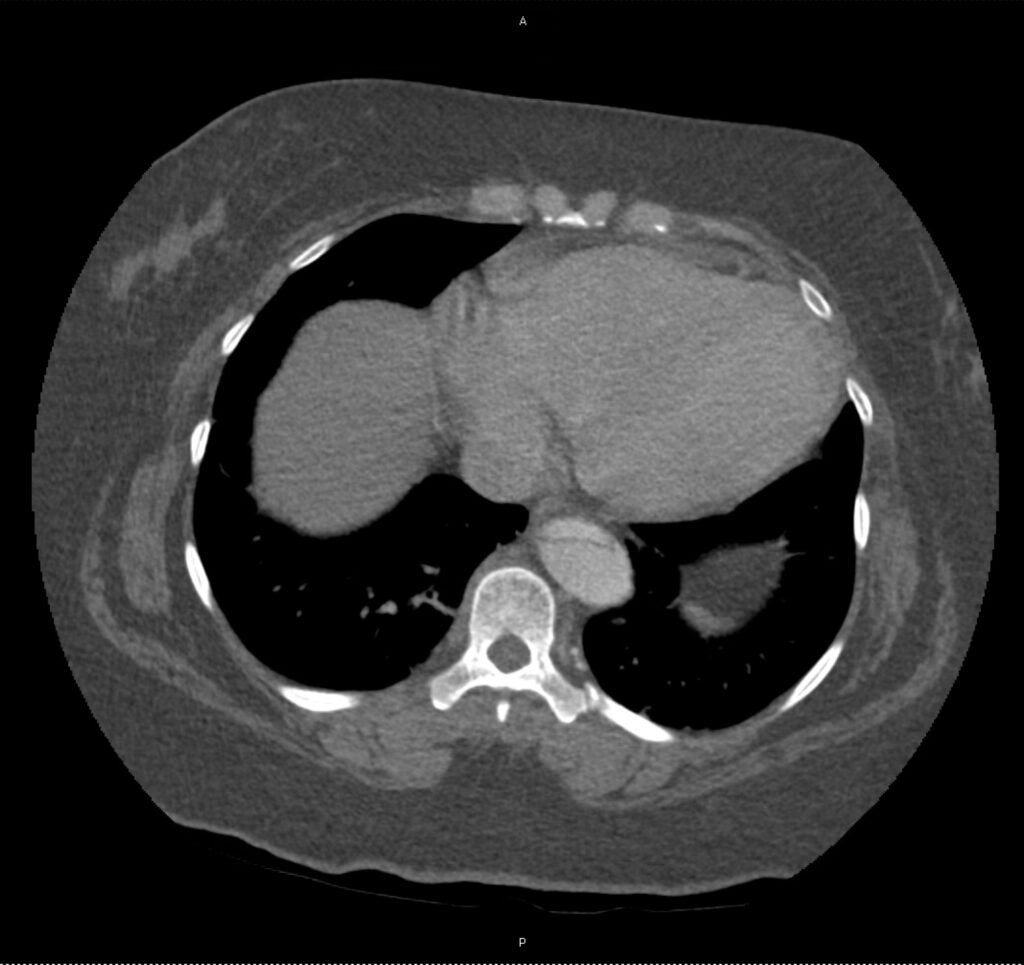

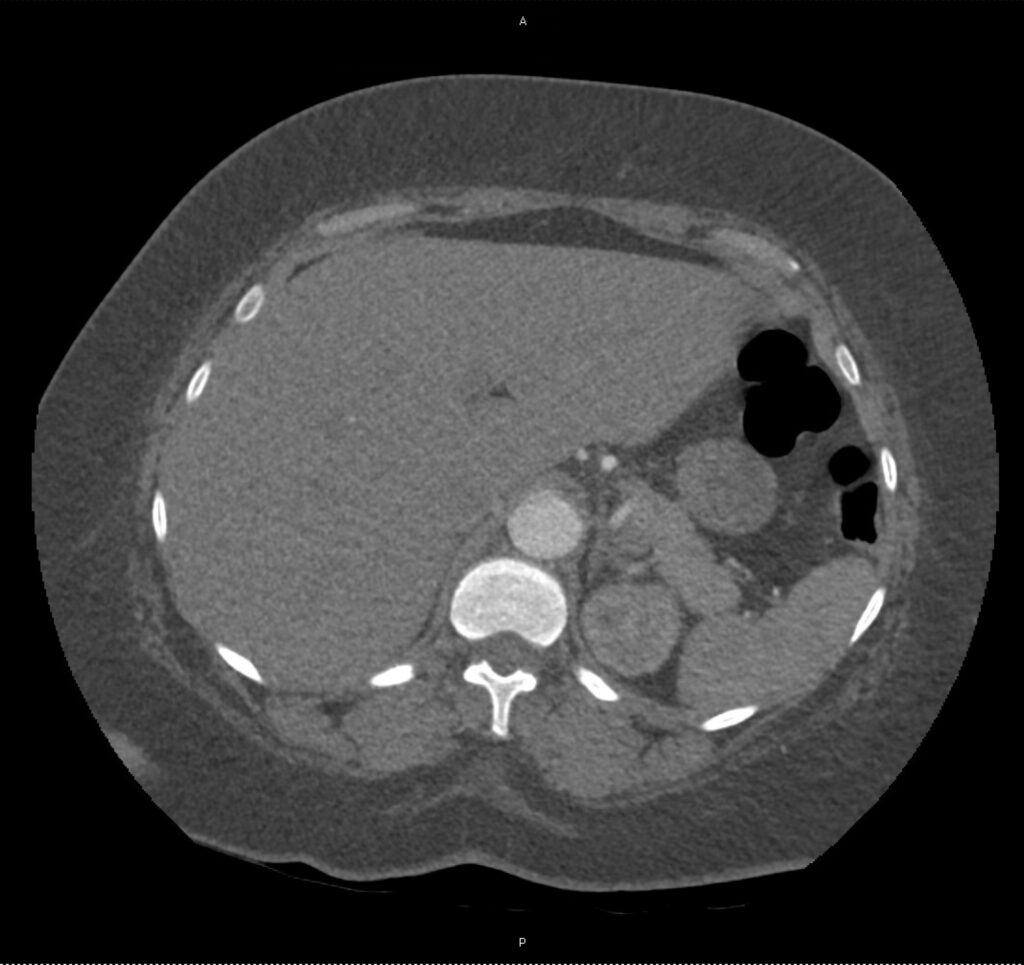

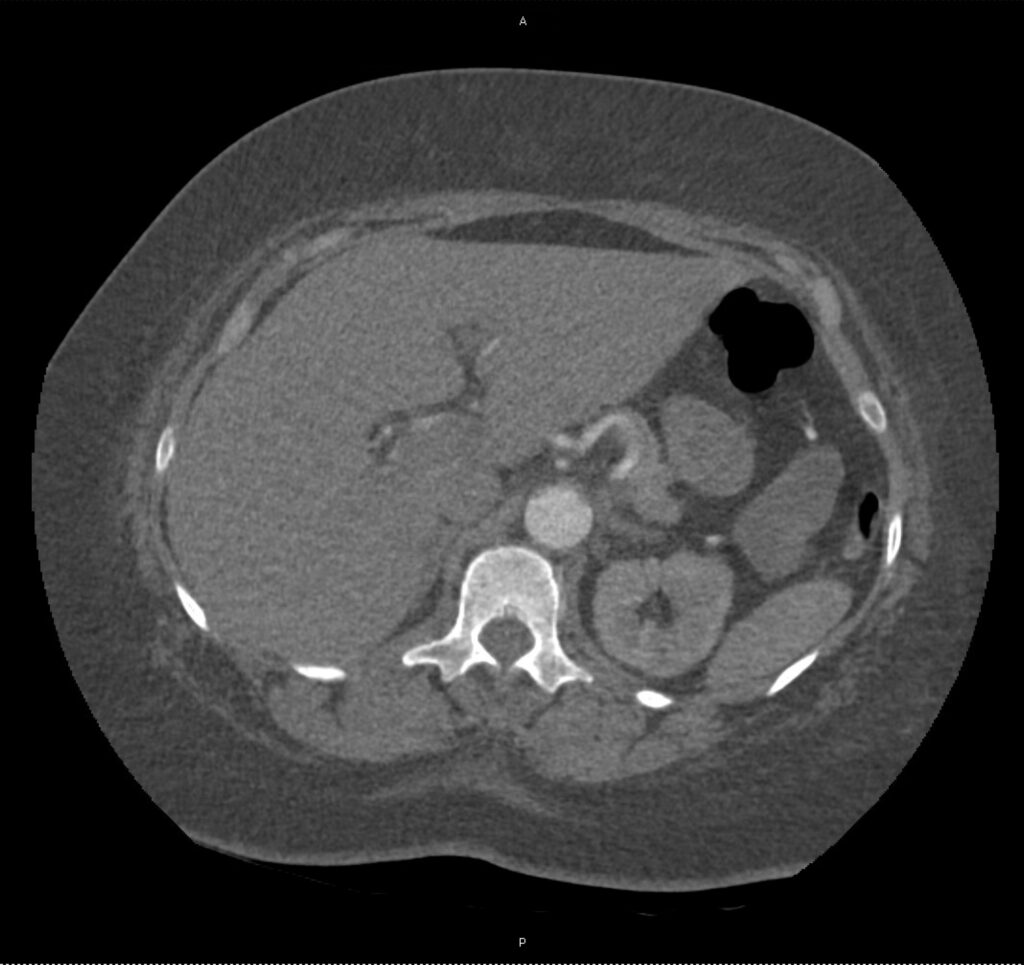

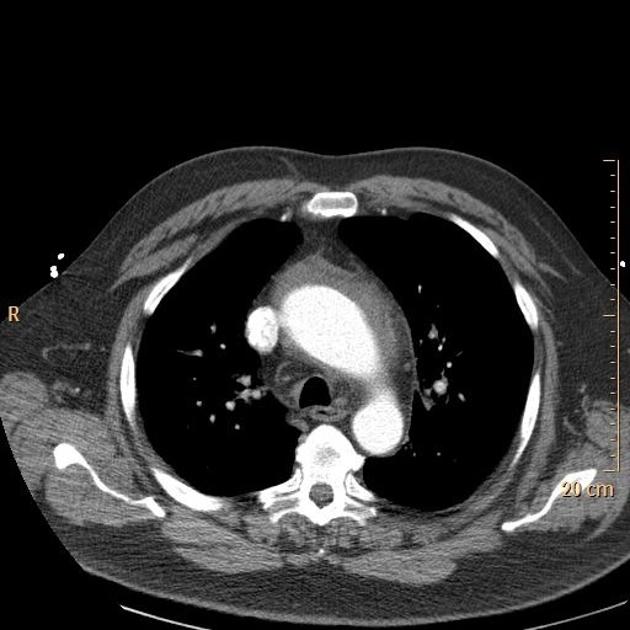

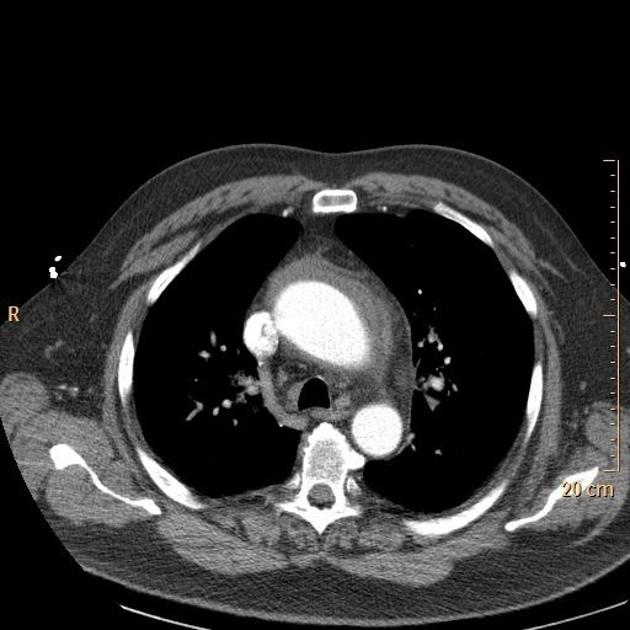

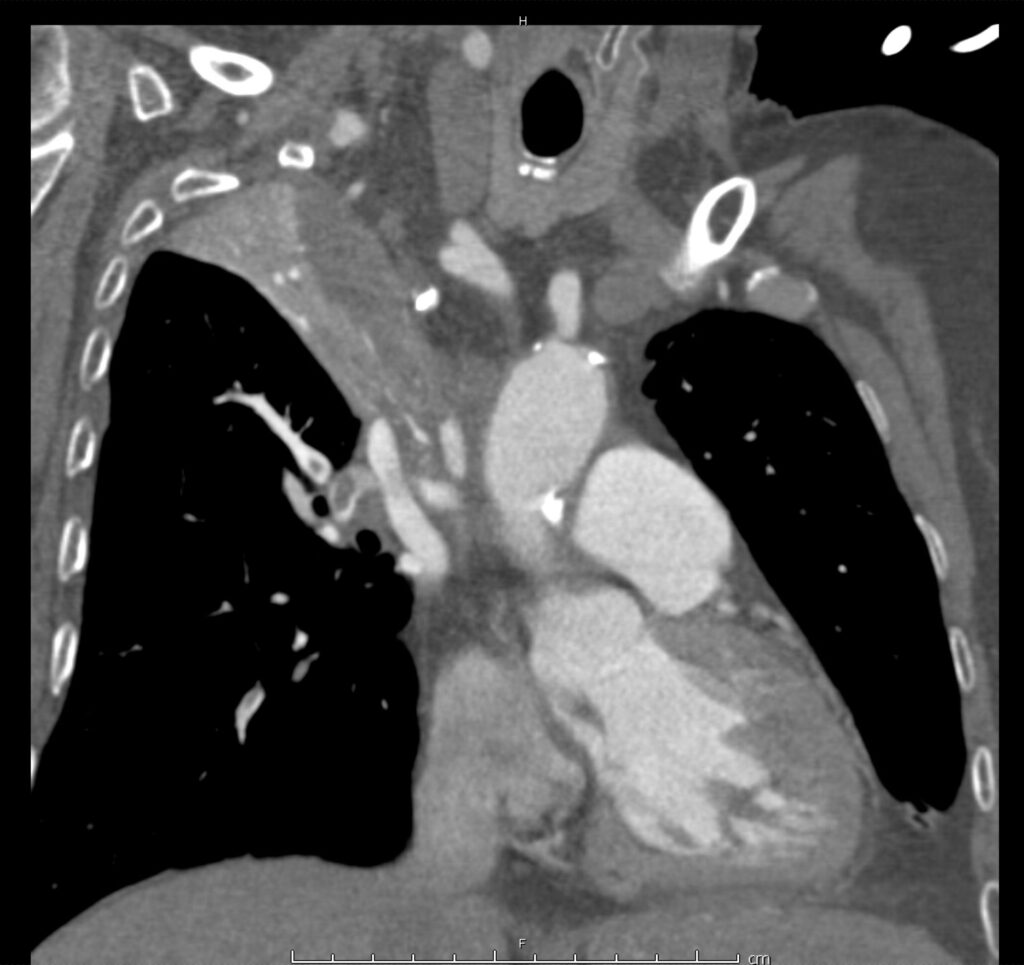

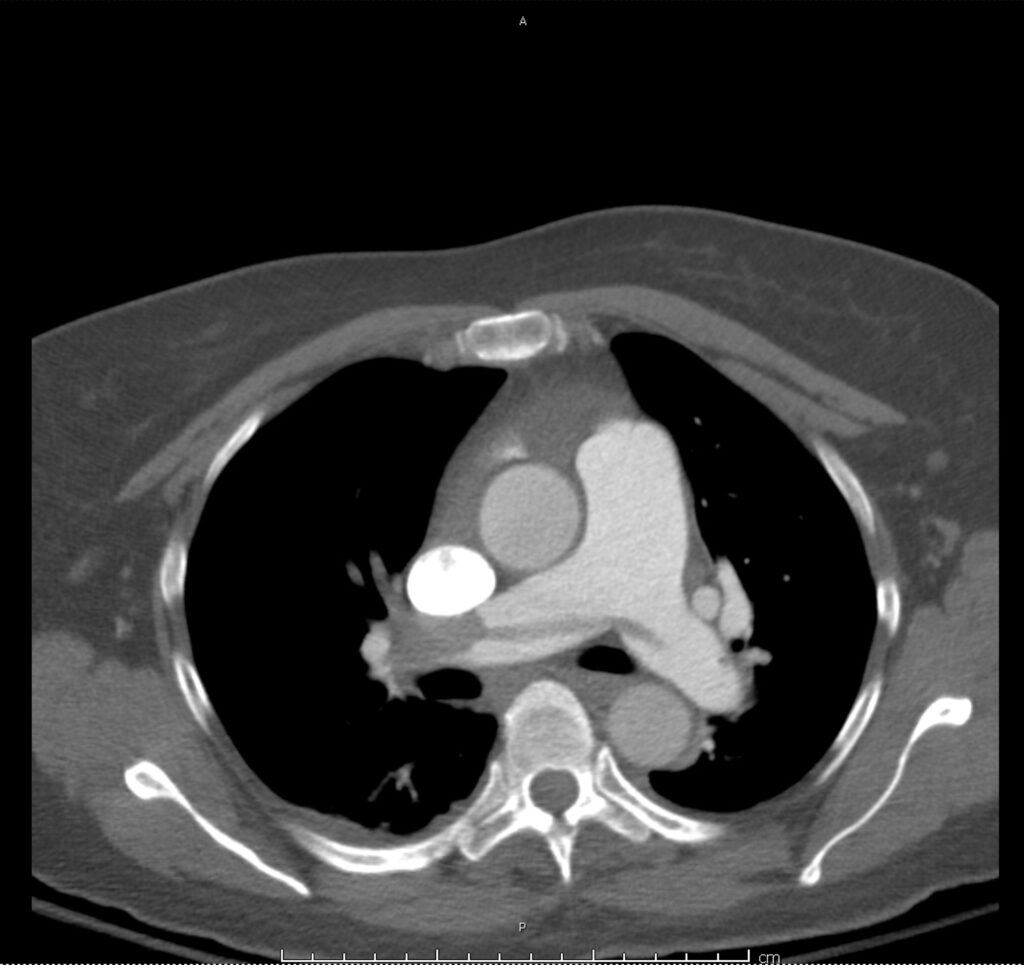

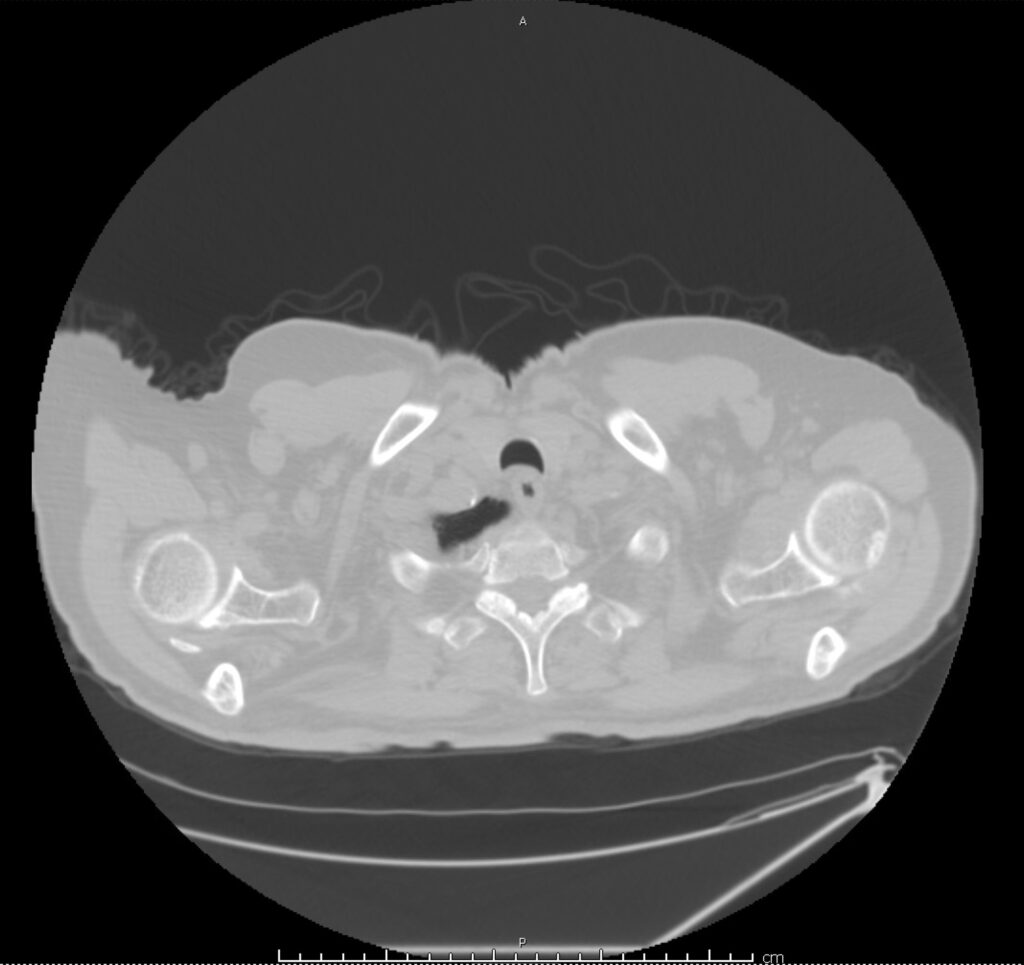

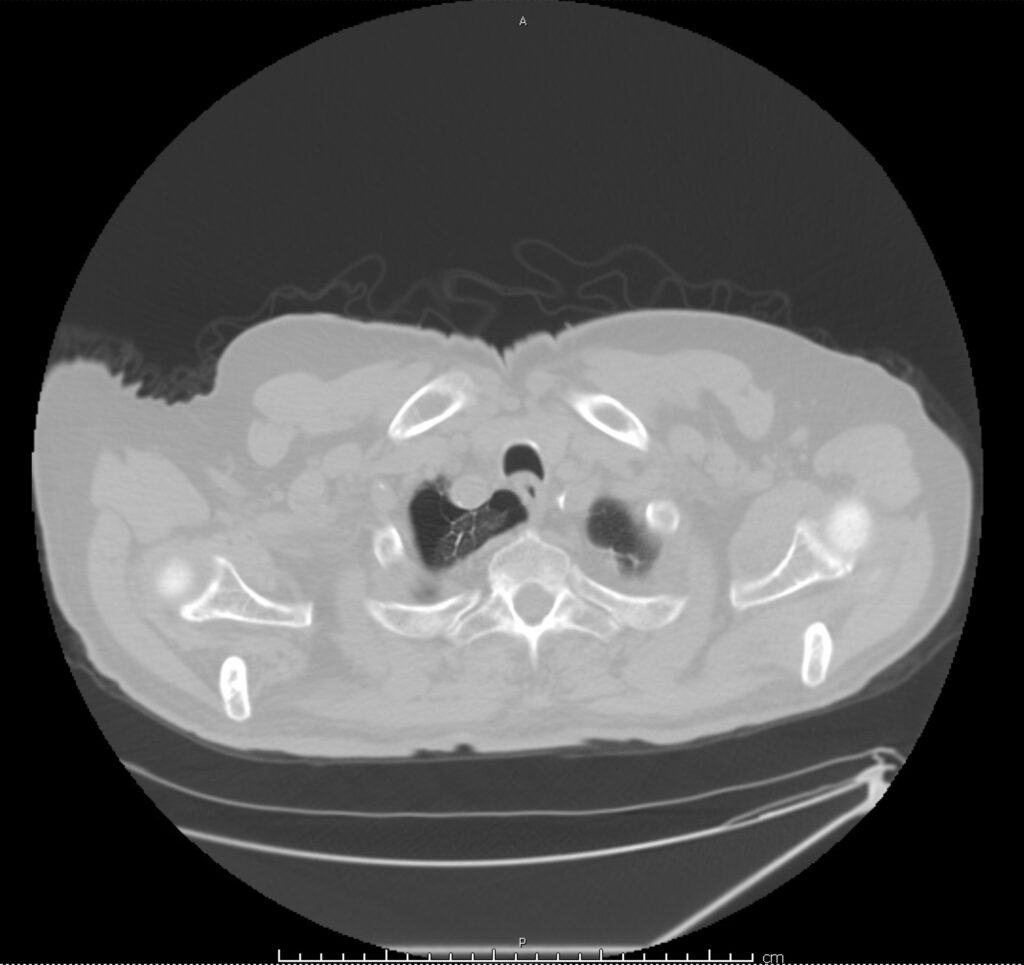

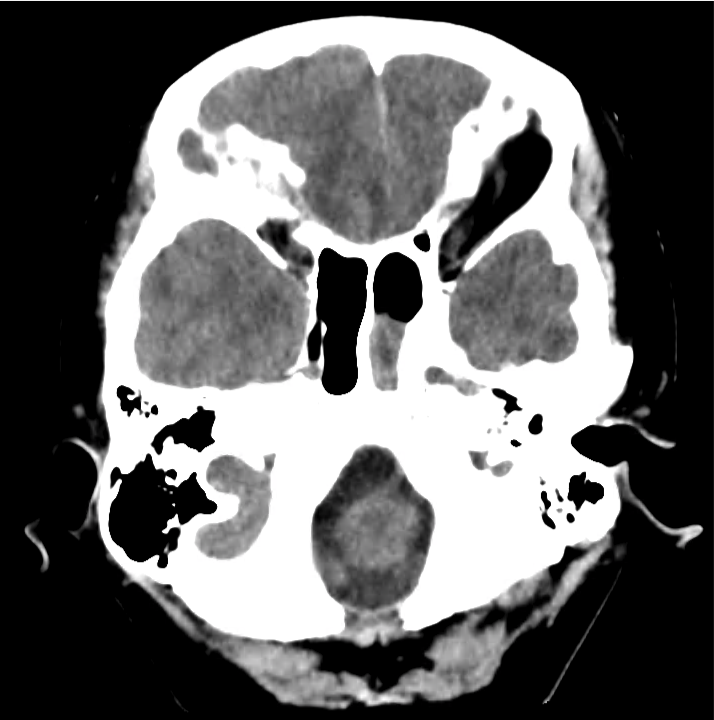

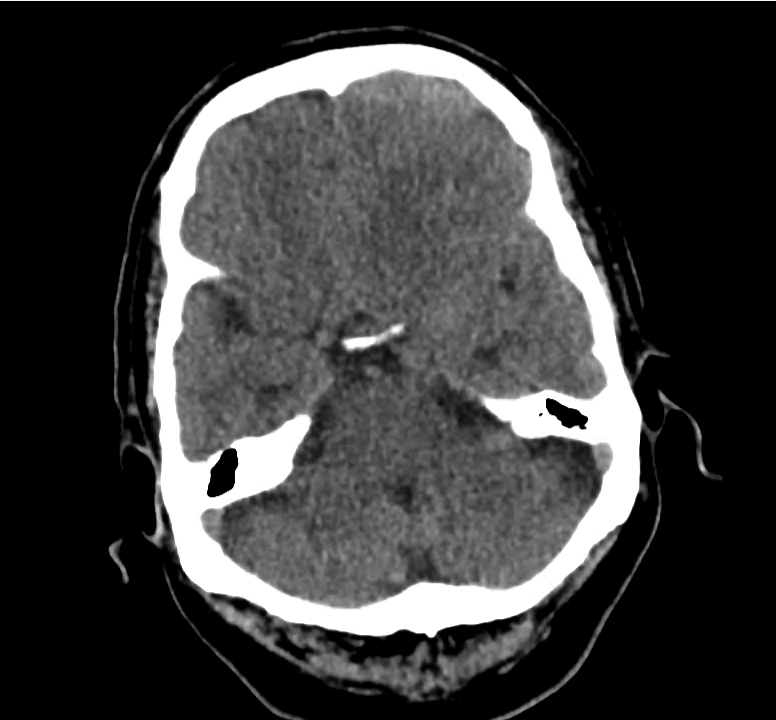

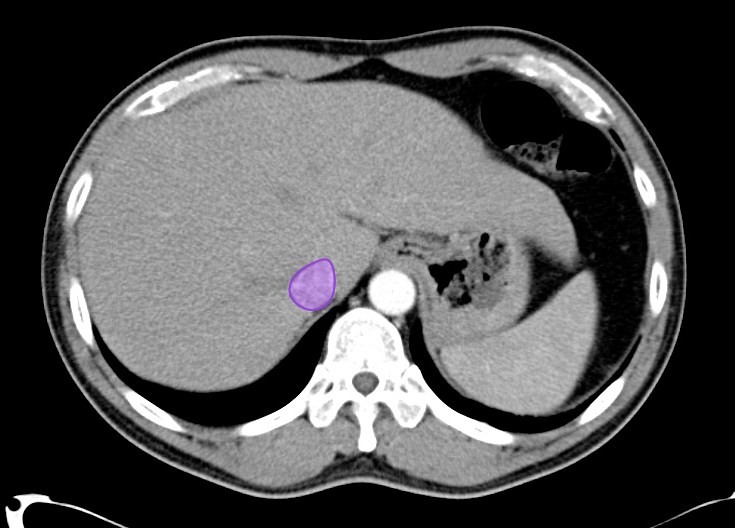

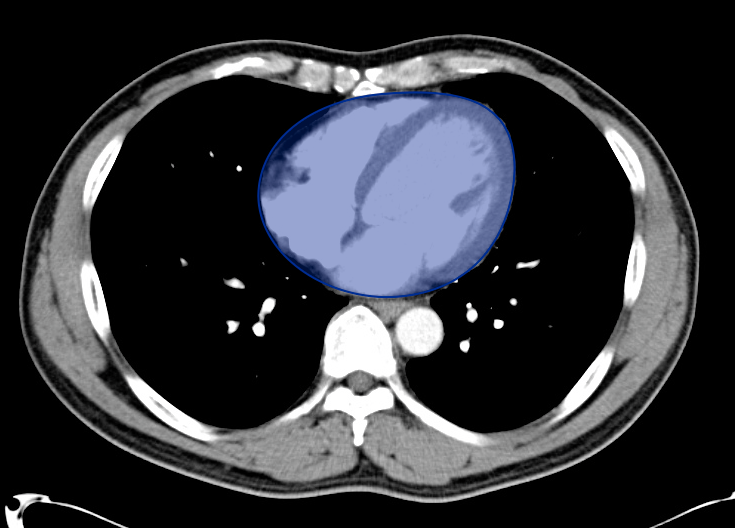

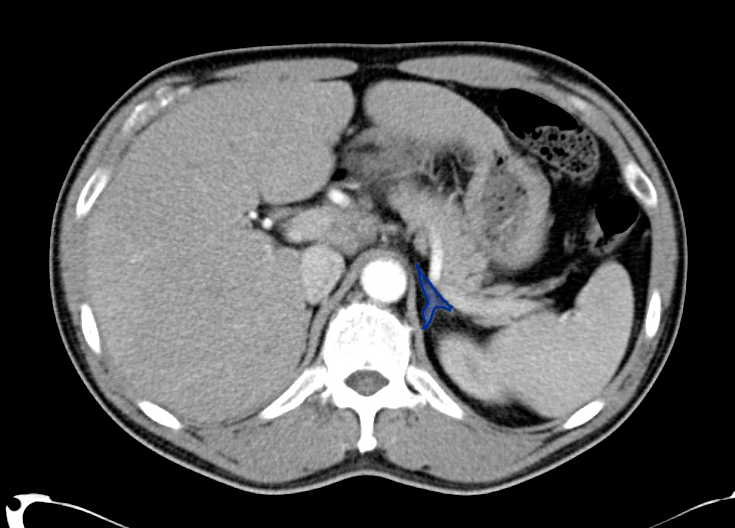

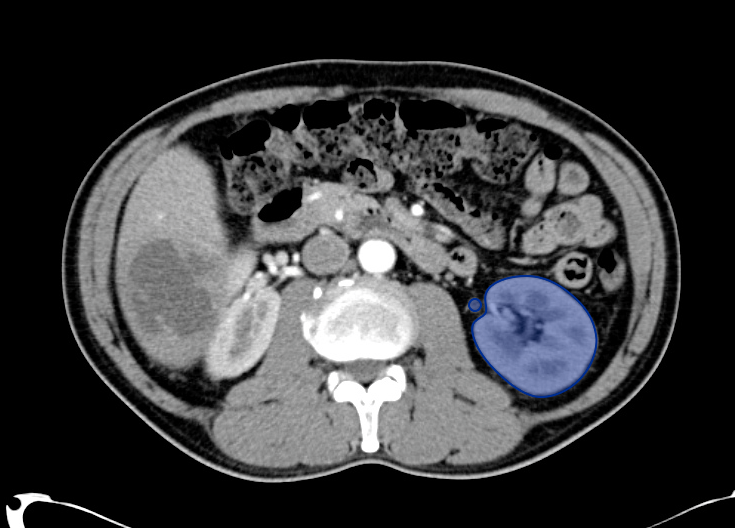

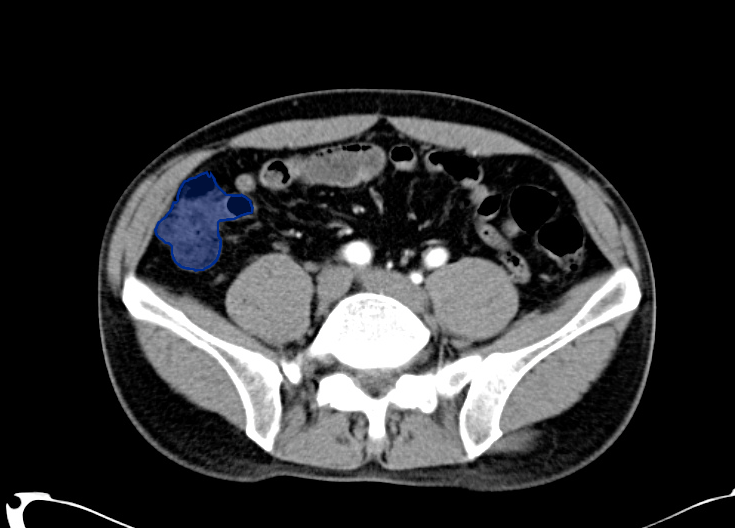

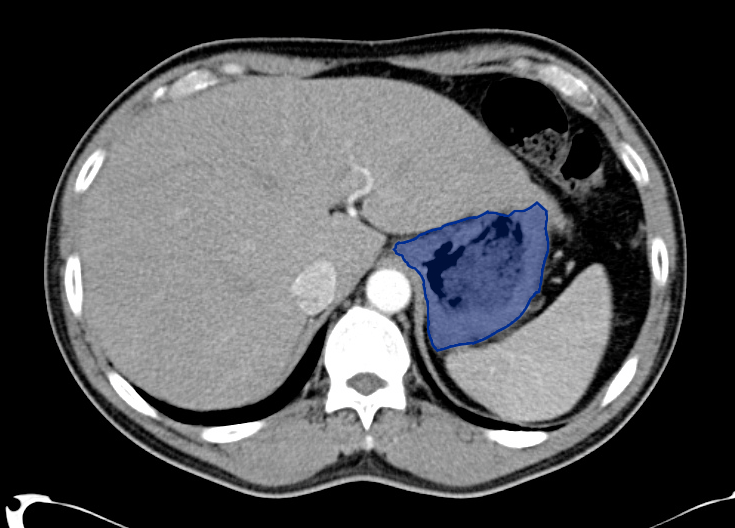

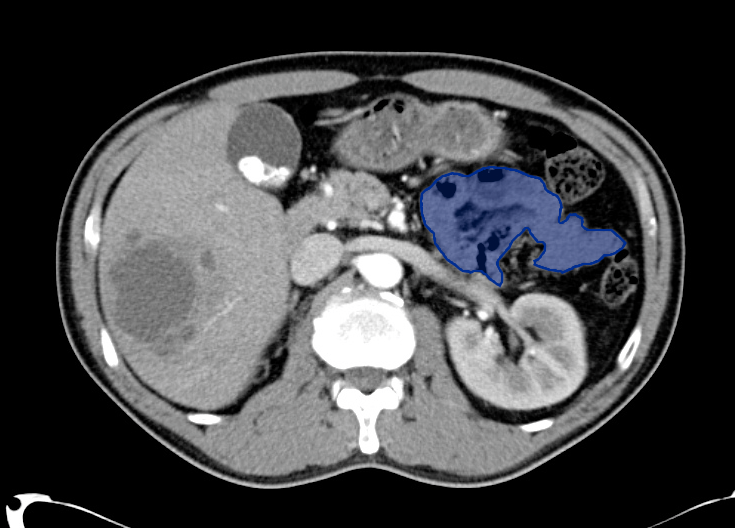

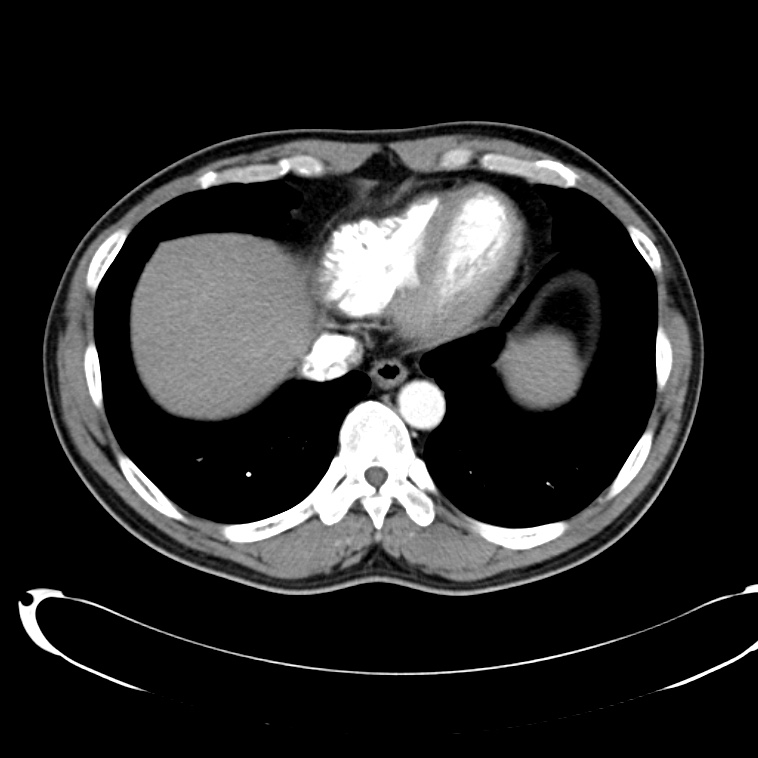

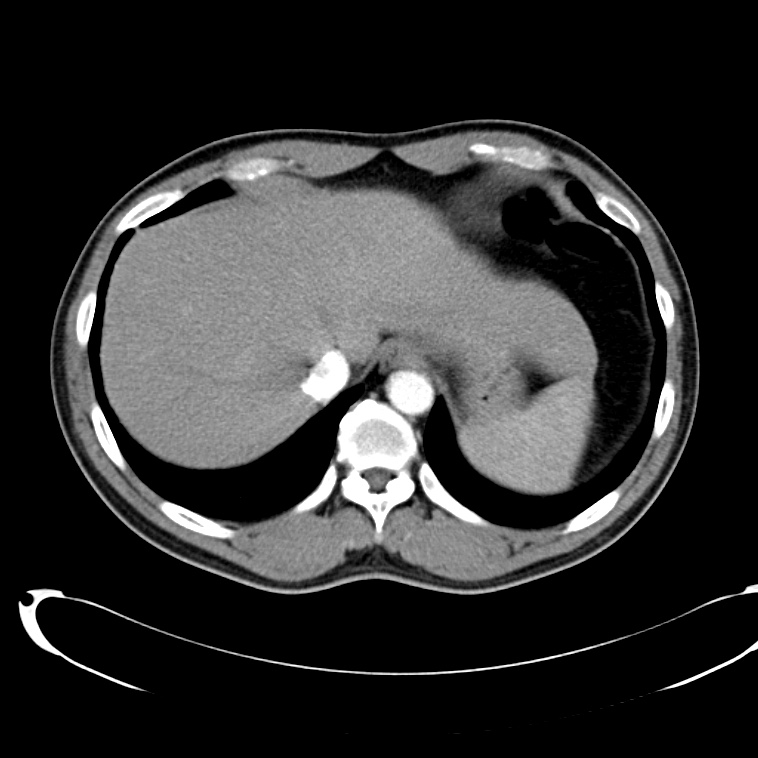

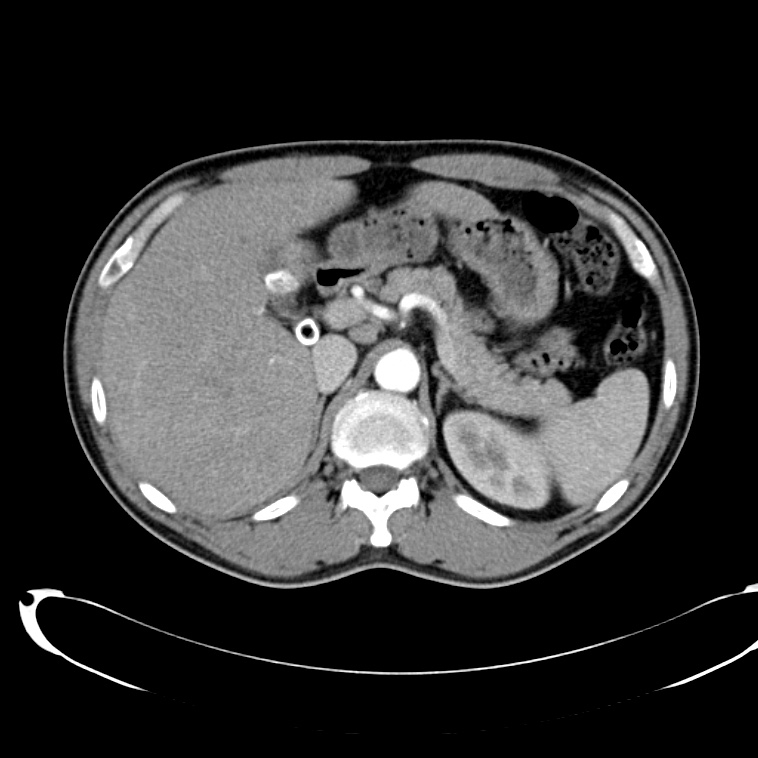

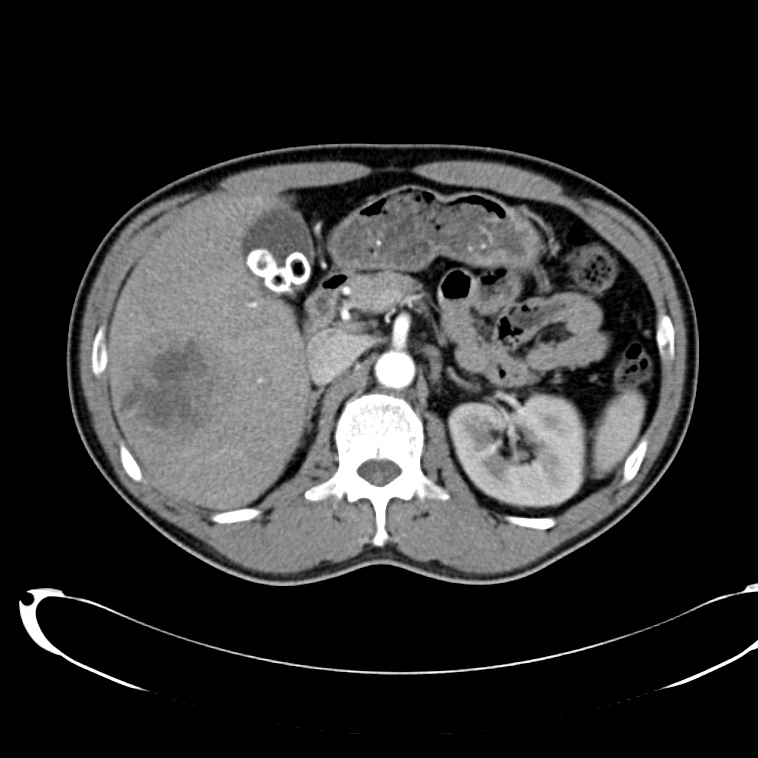

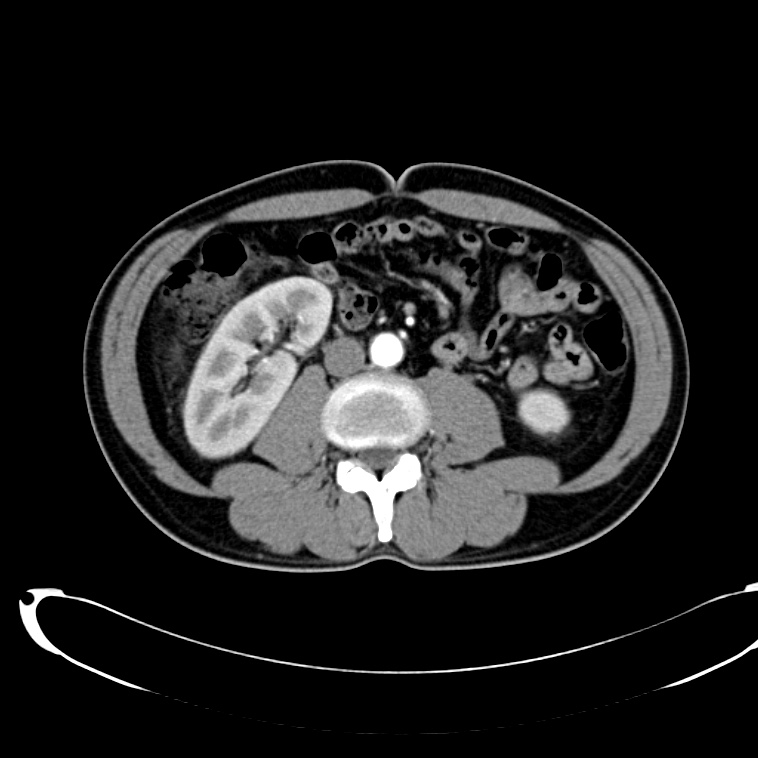

Example #1

CT Head Interpretation

- Ill-defined lesion in right parietal white matter with a large amount of surrounding vasogenic edema with midline shift and right uncal herniation.

- Acute on subacute right extra-axial subdural hematoma.

- Effacement of basilar cisterns.

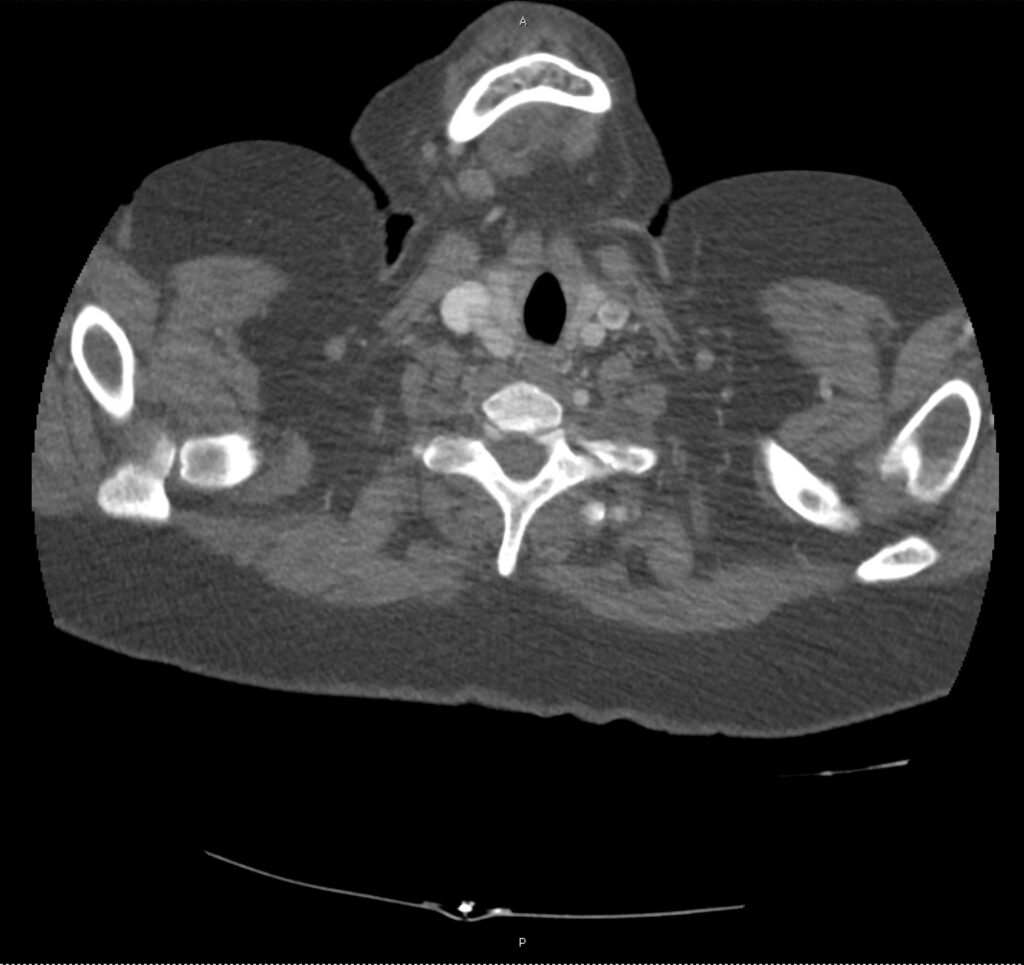

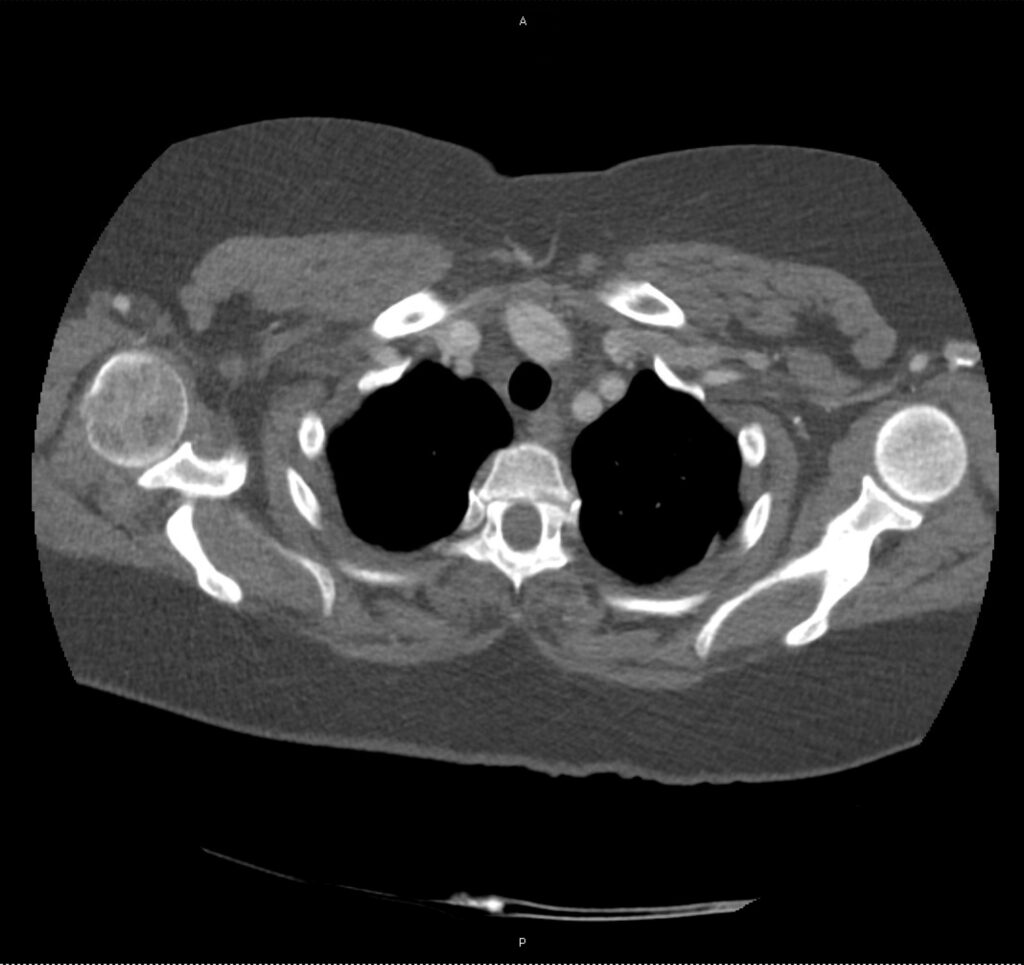

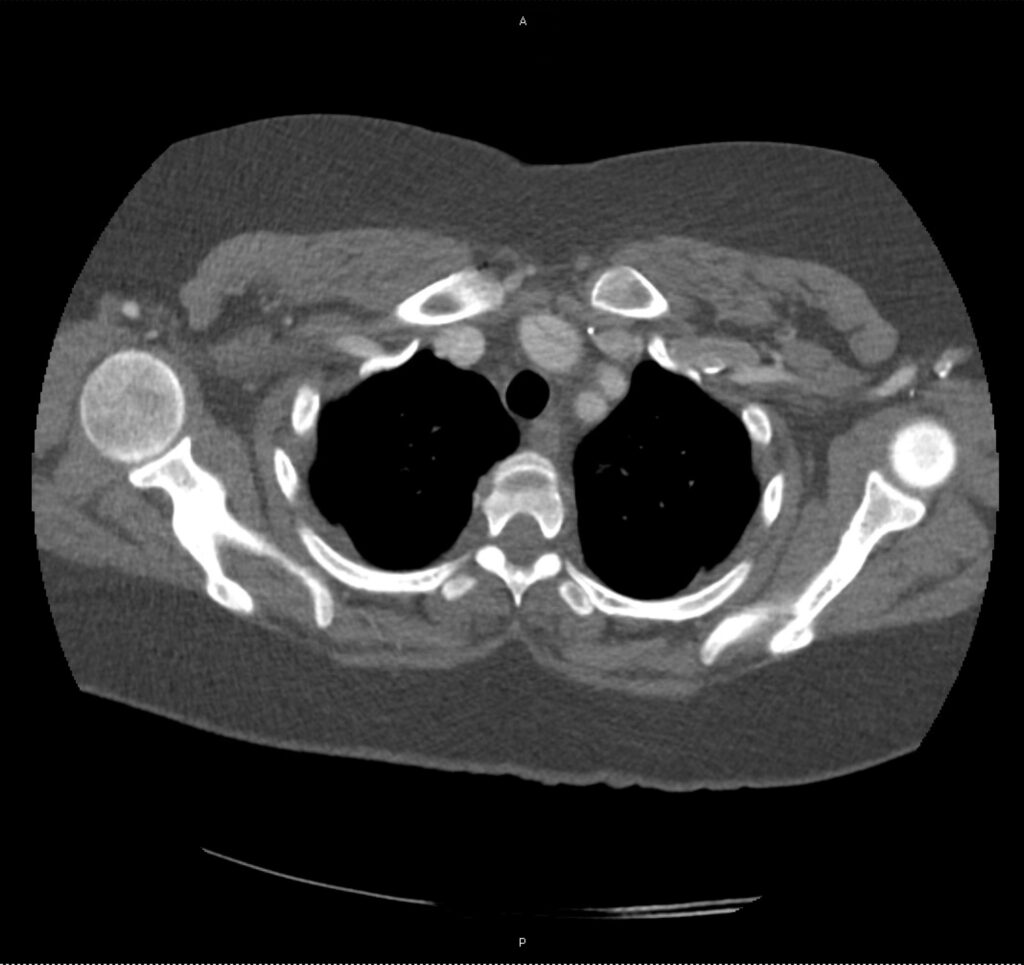

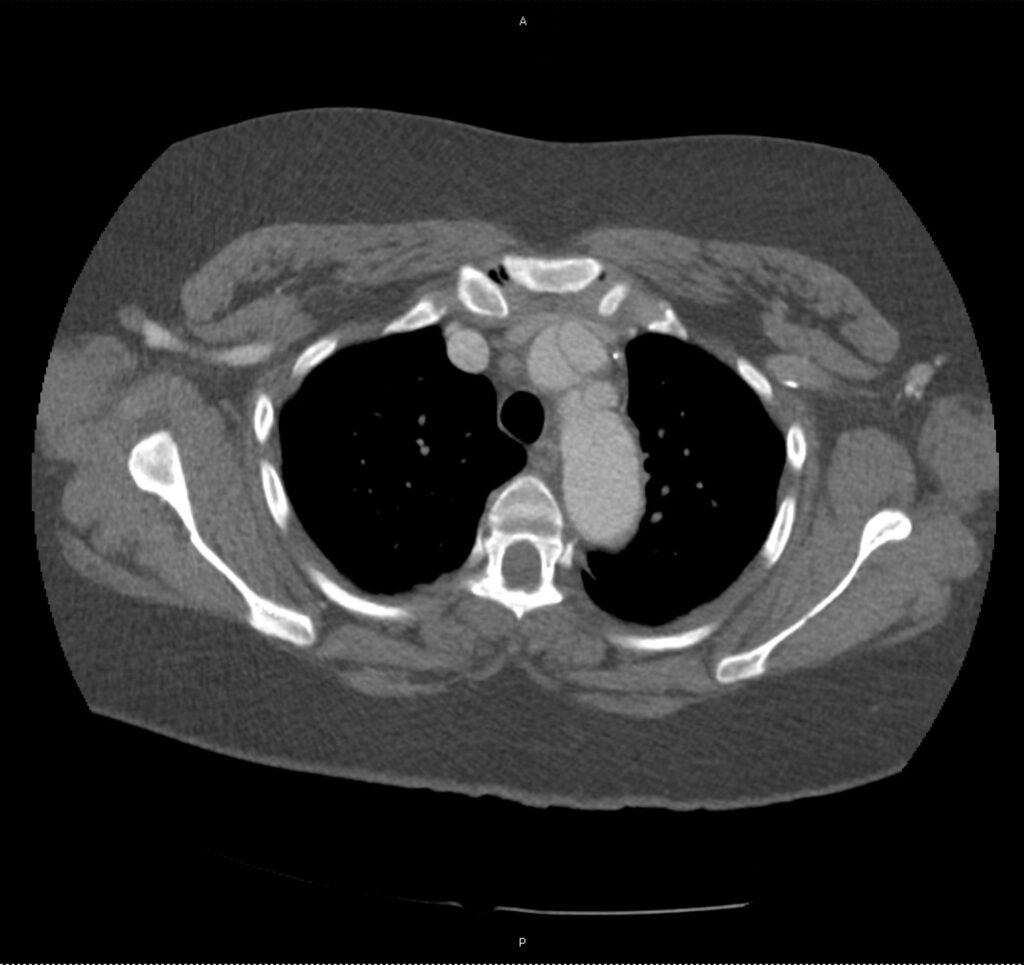

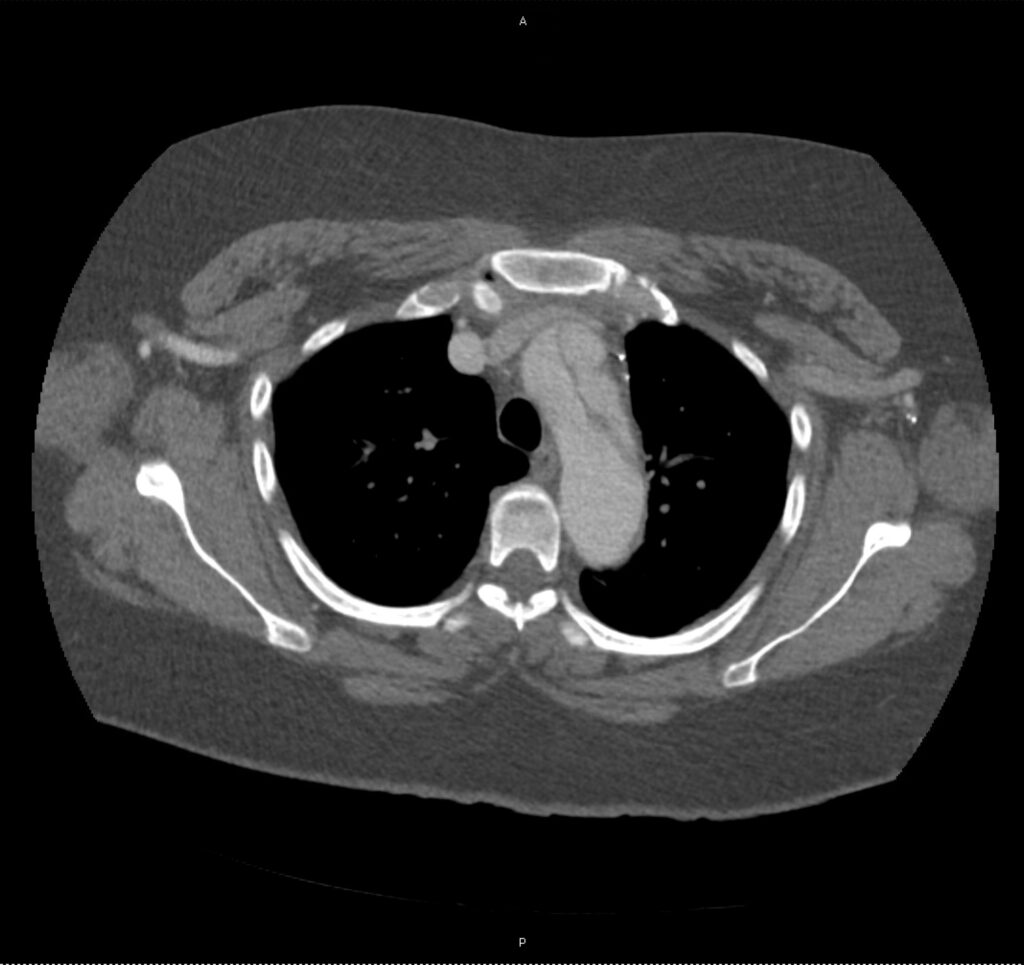

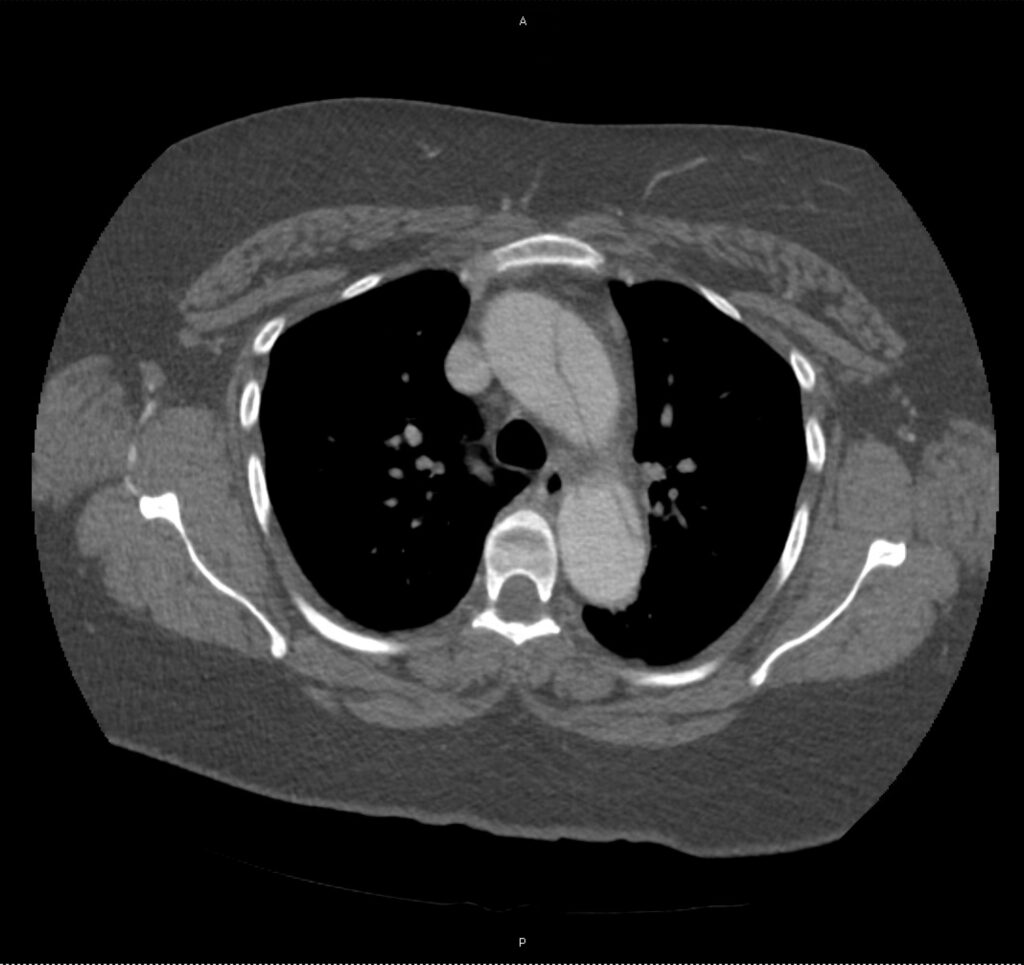

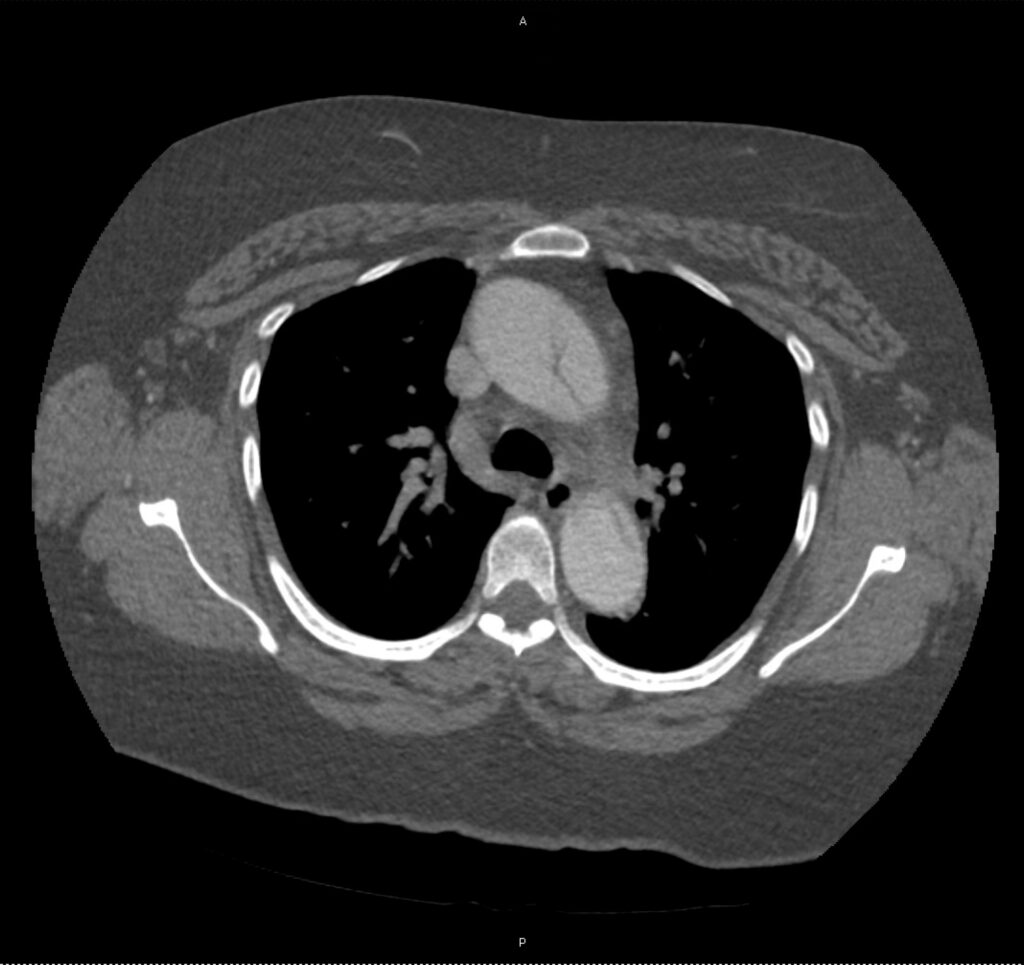

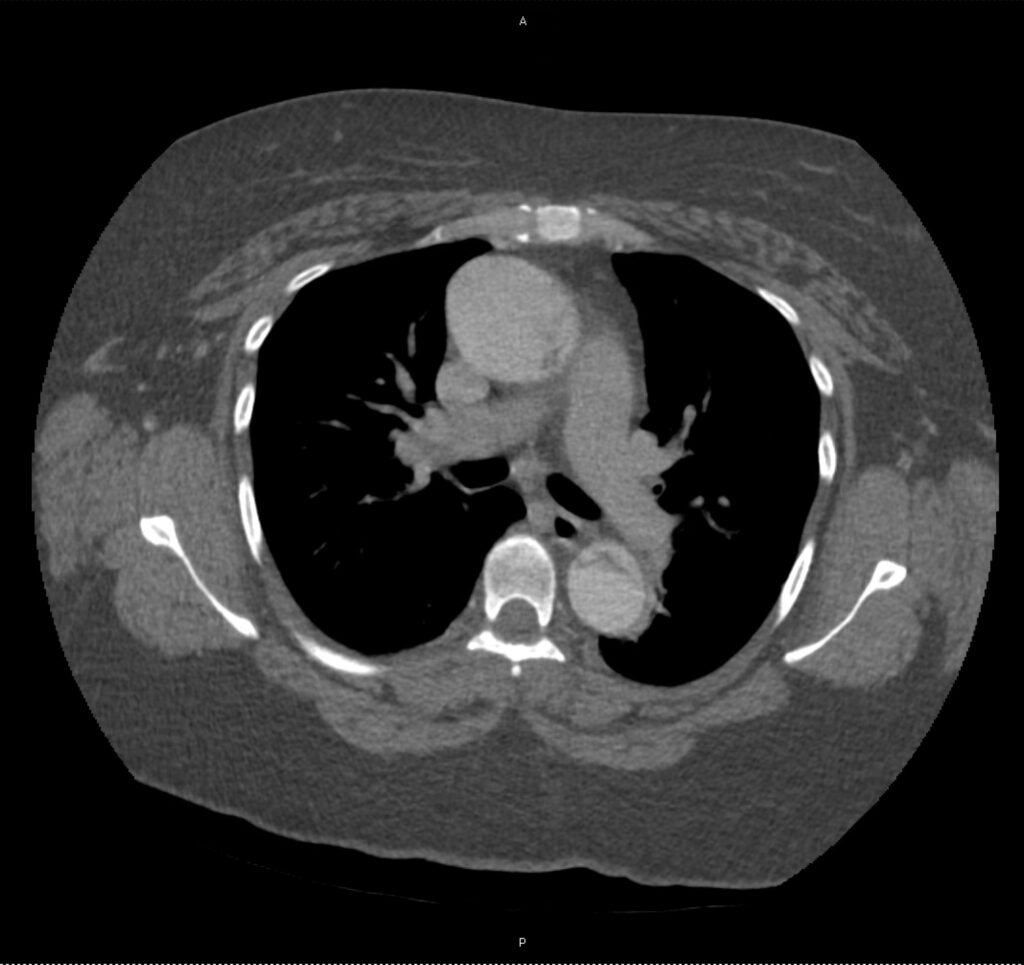

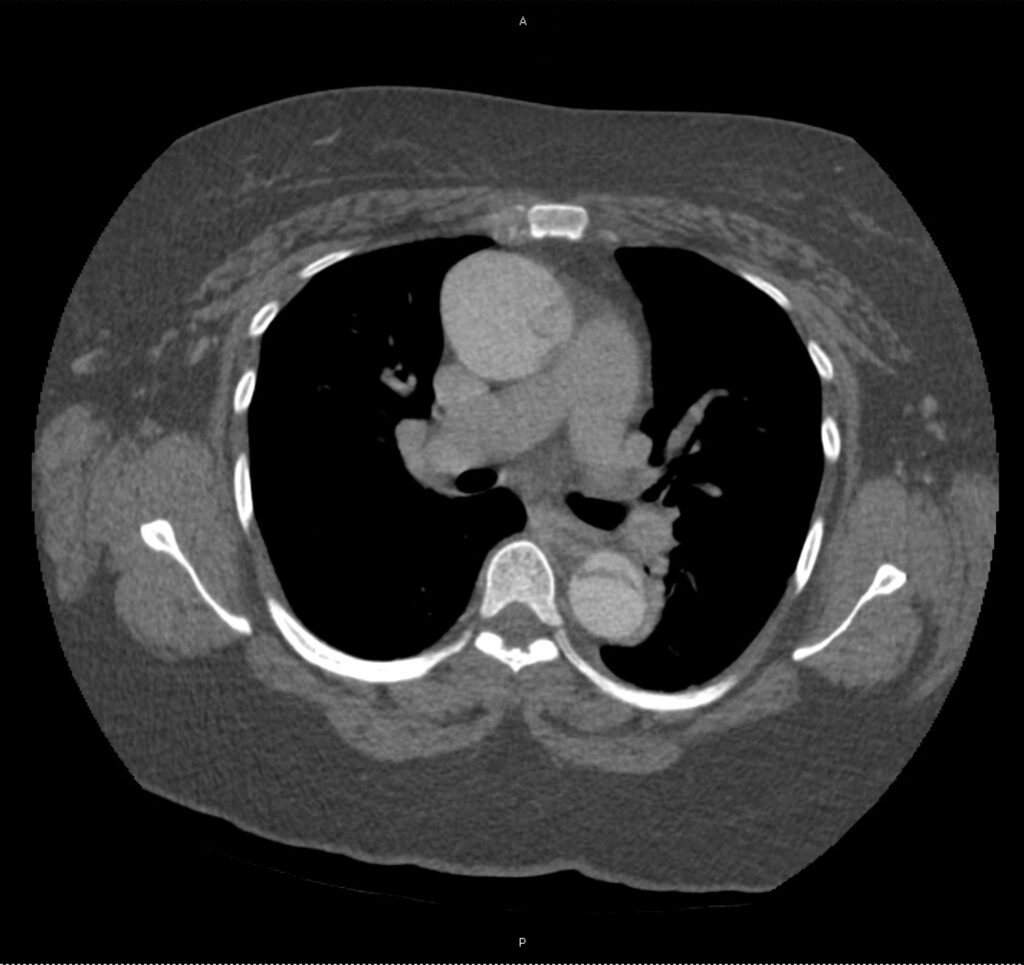

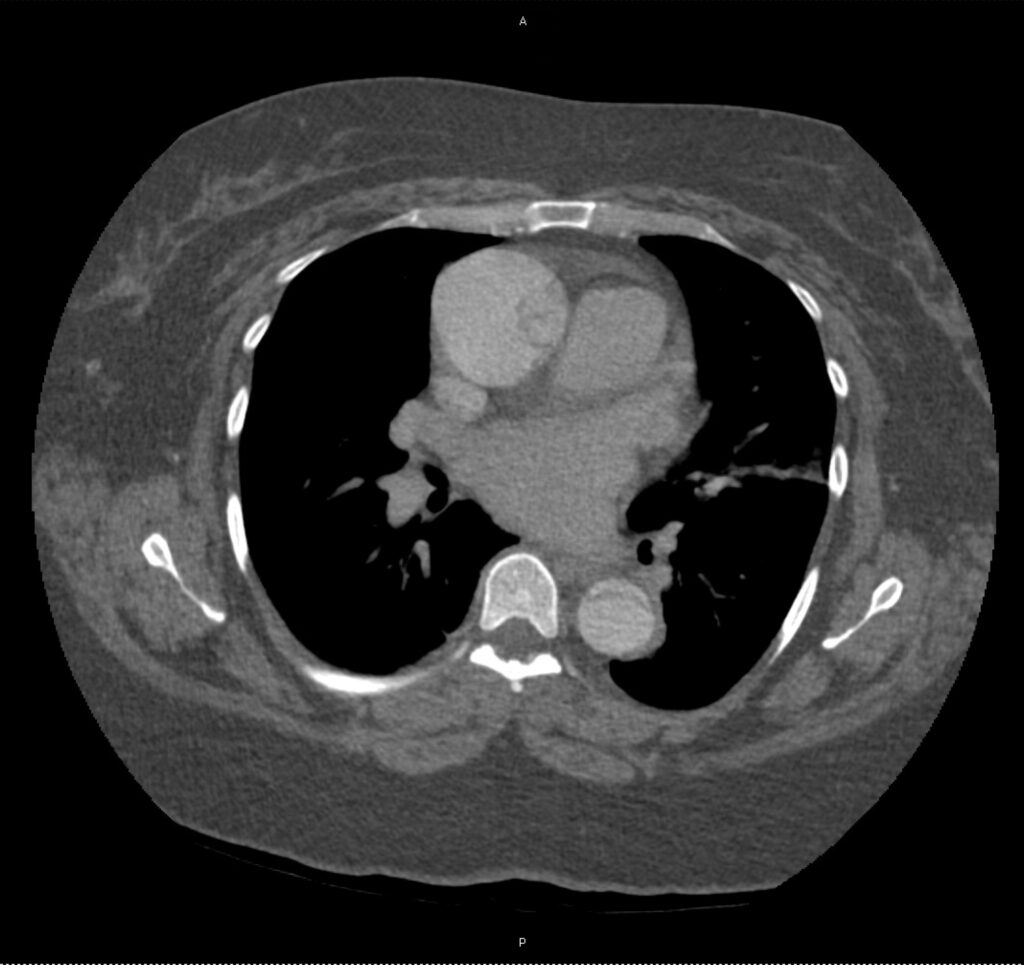

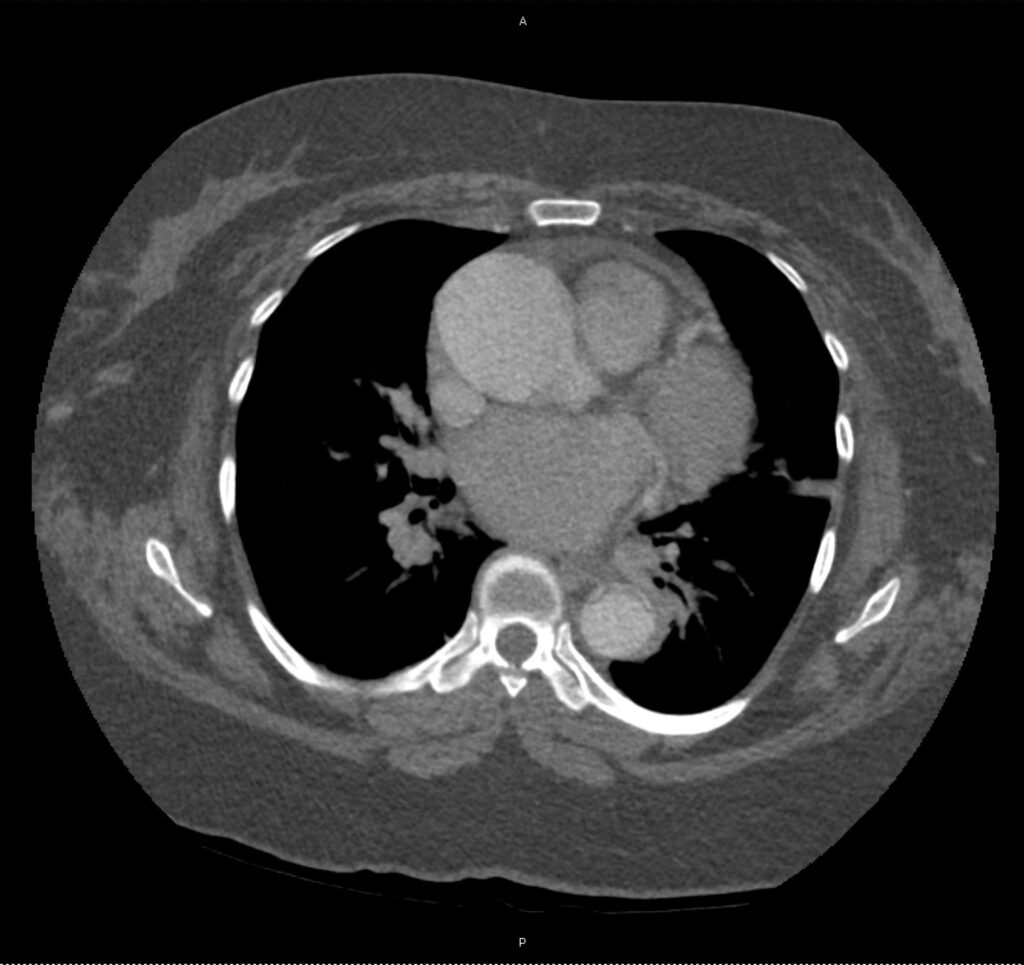

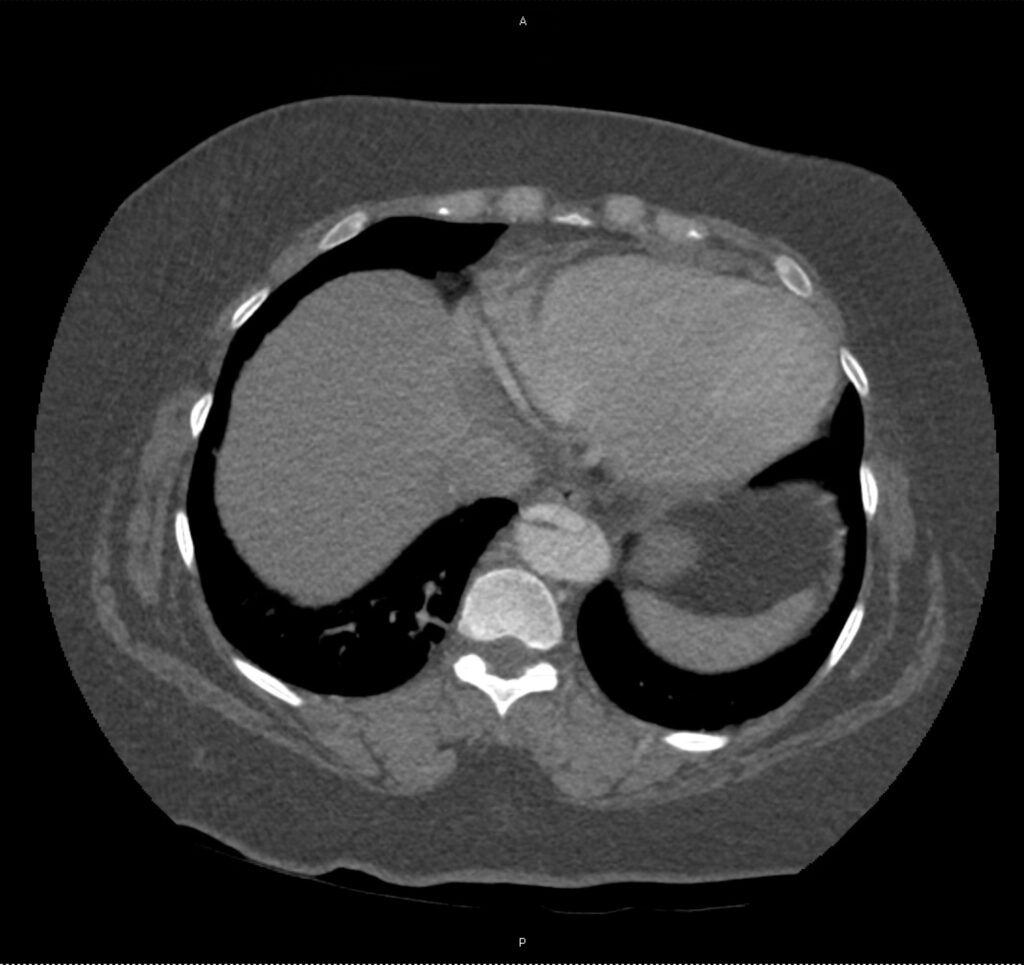

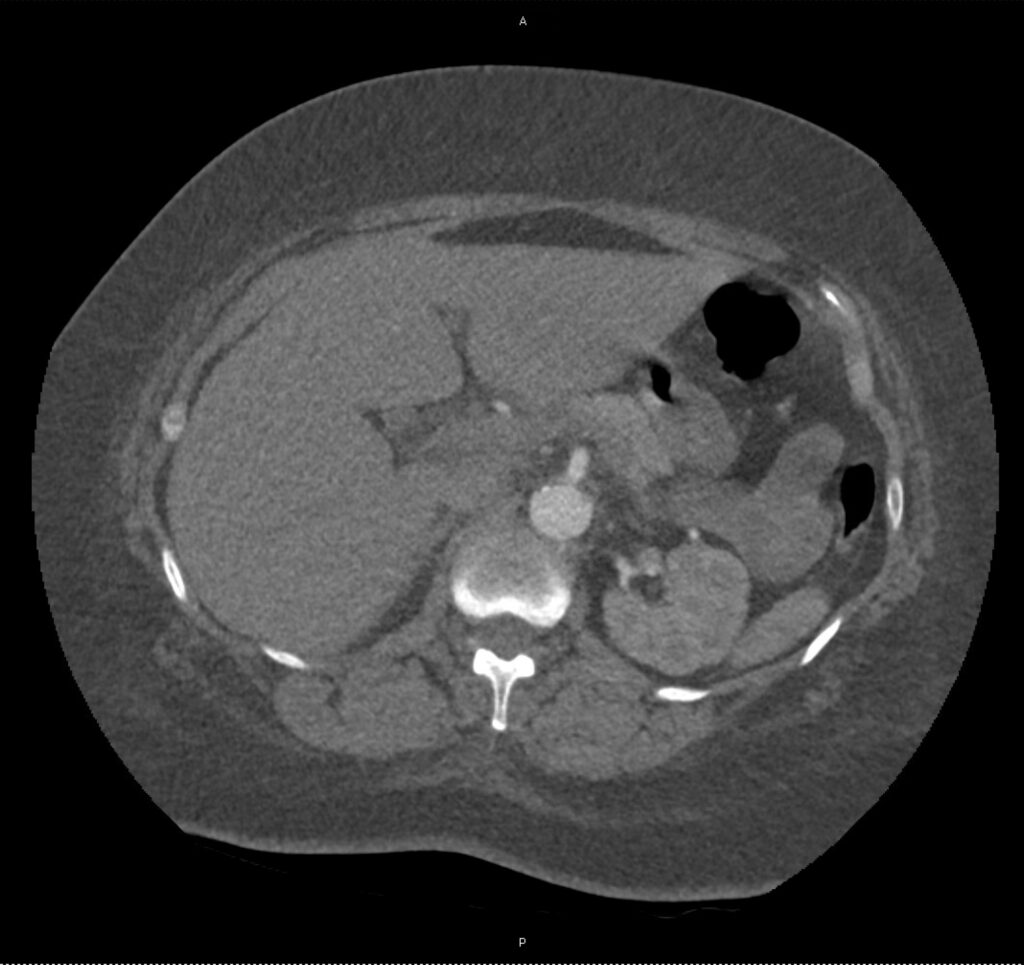

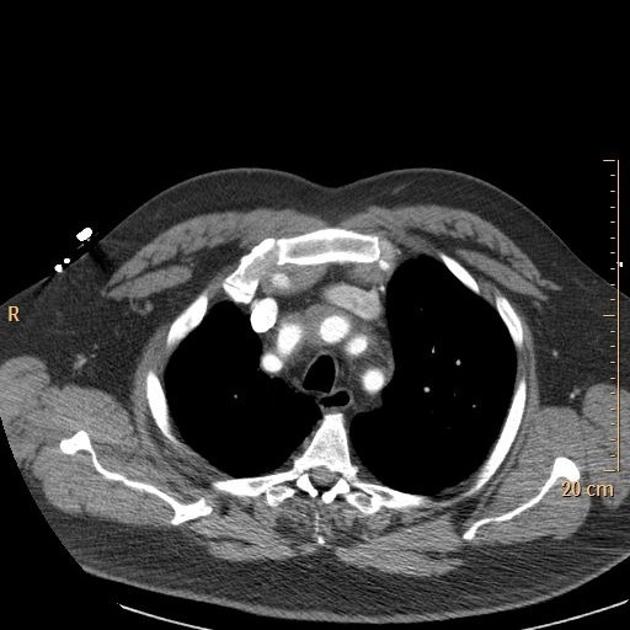

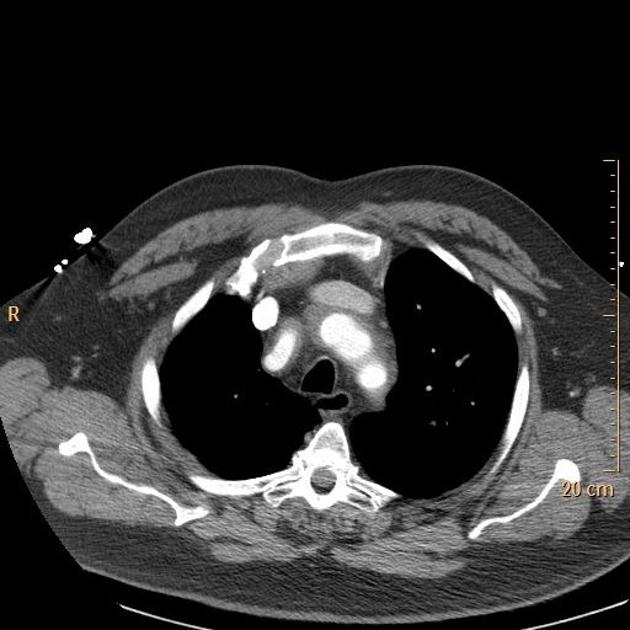

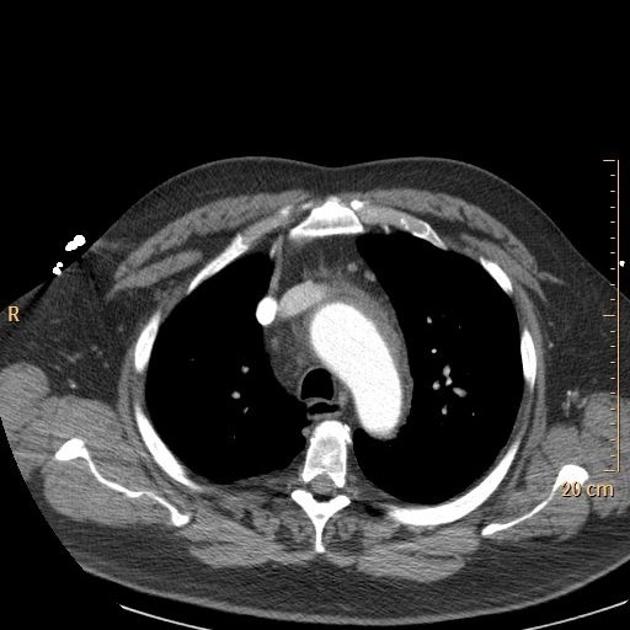

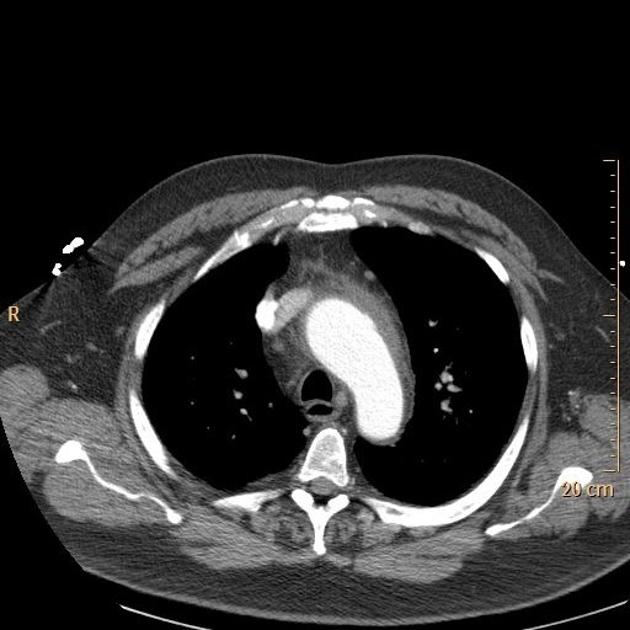

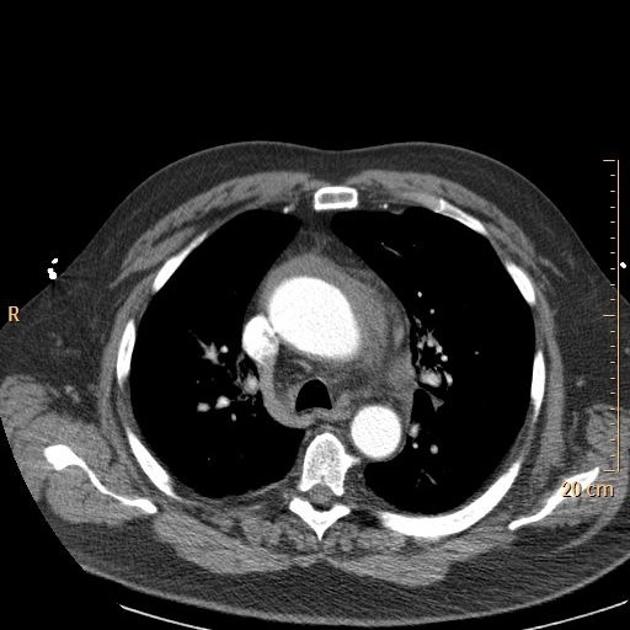

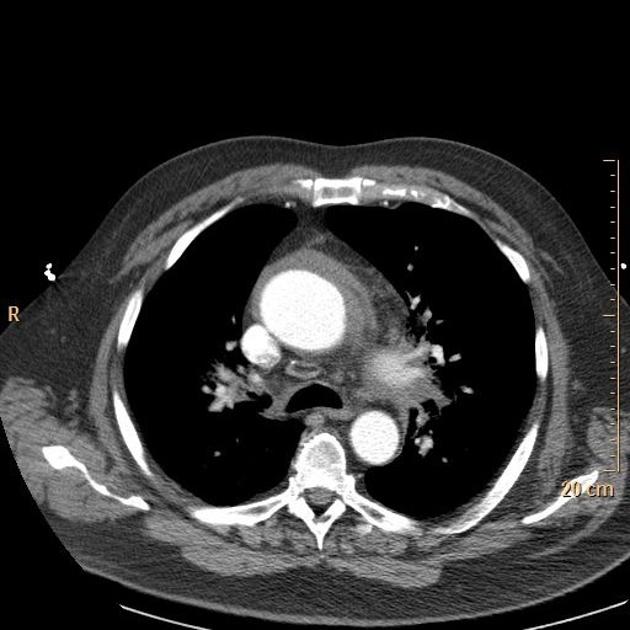

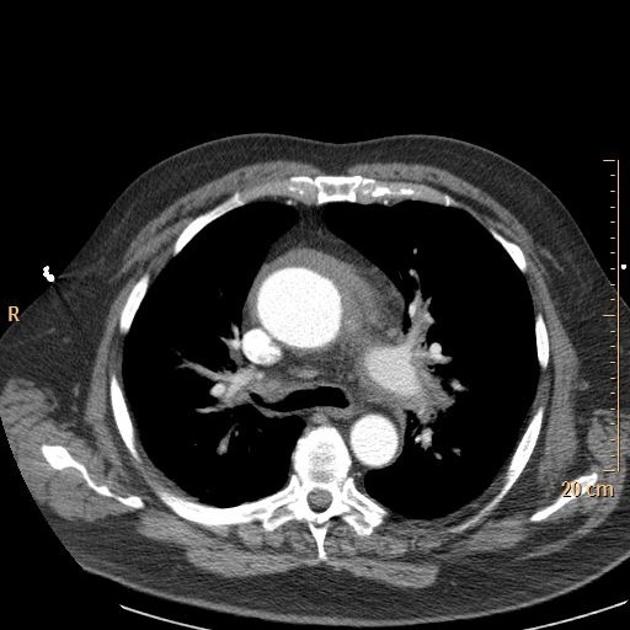

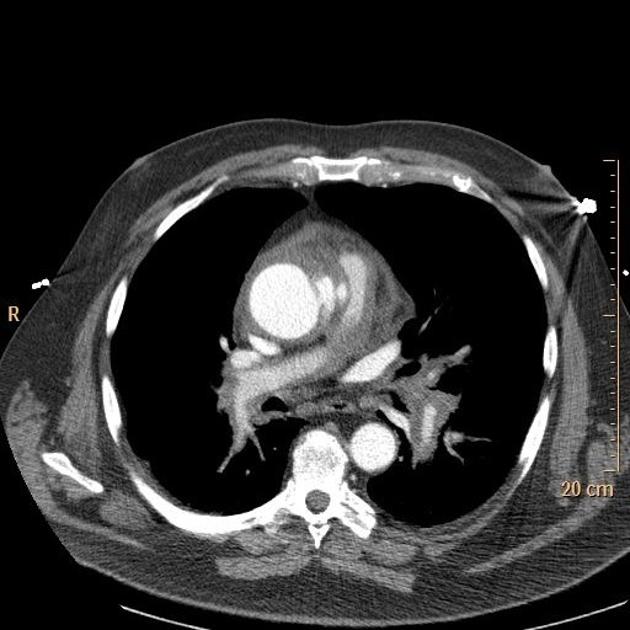

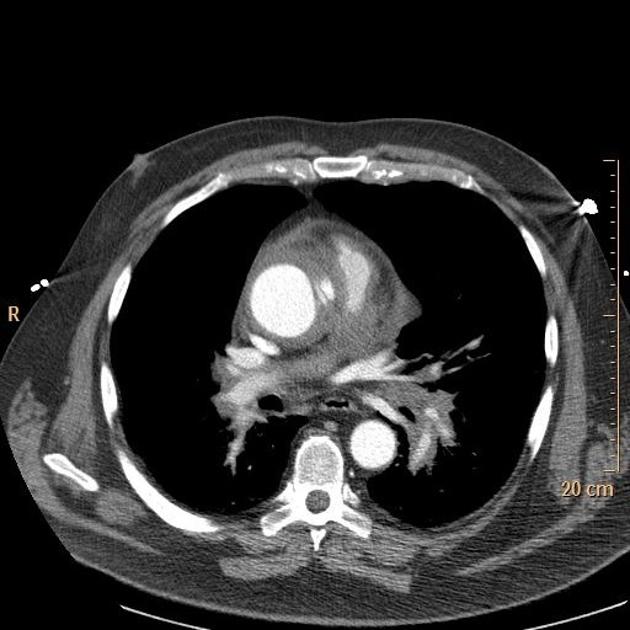

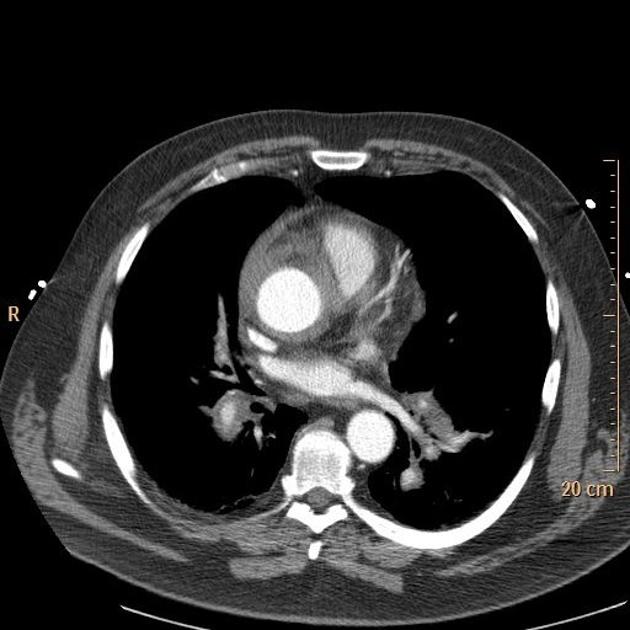

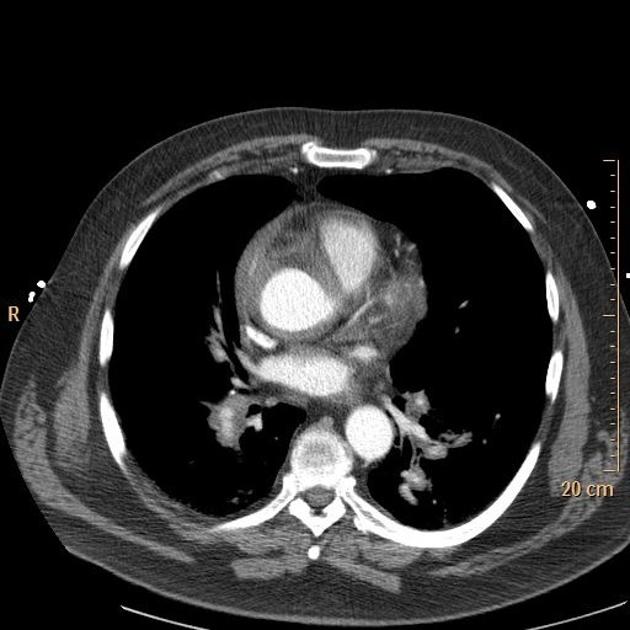

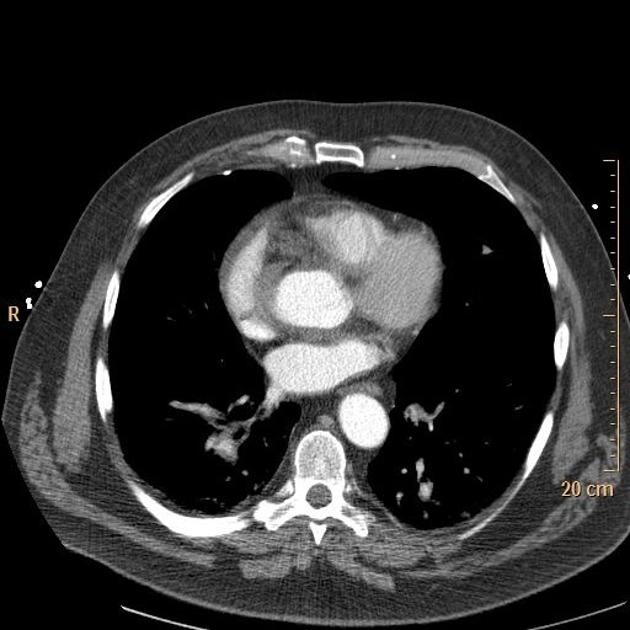

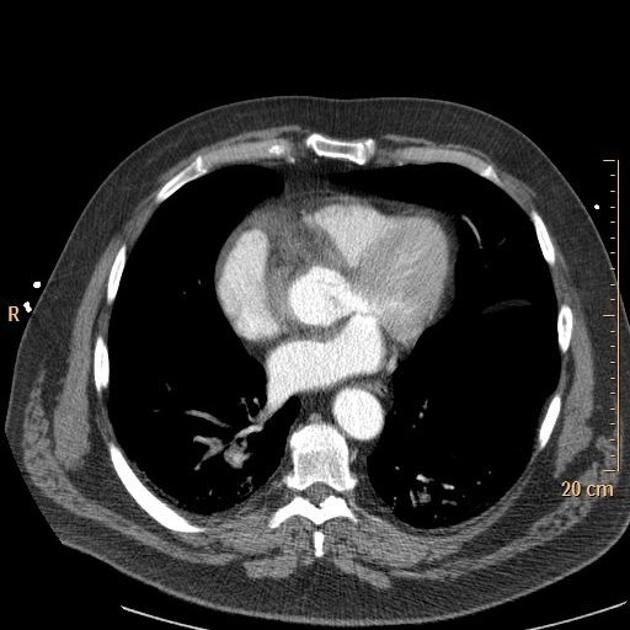

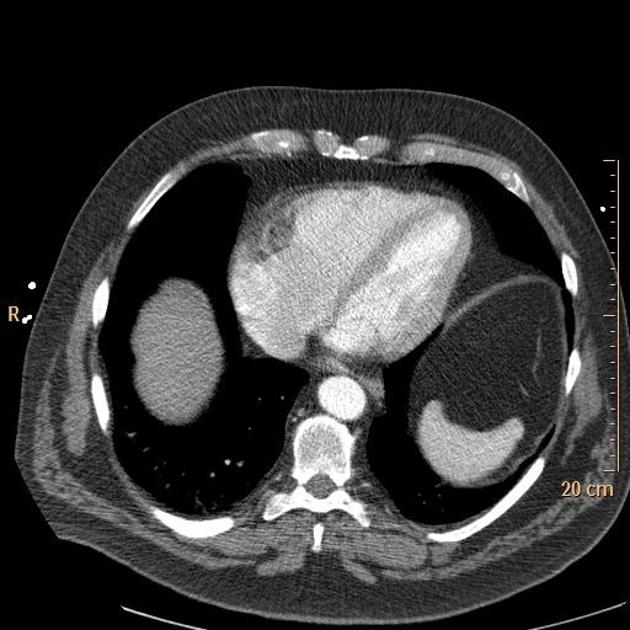

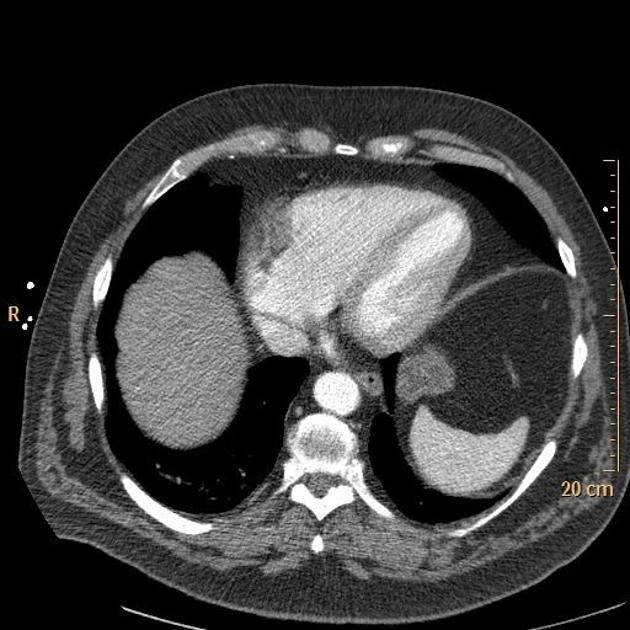

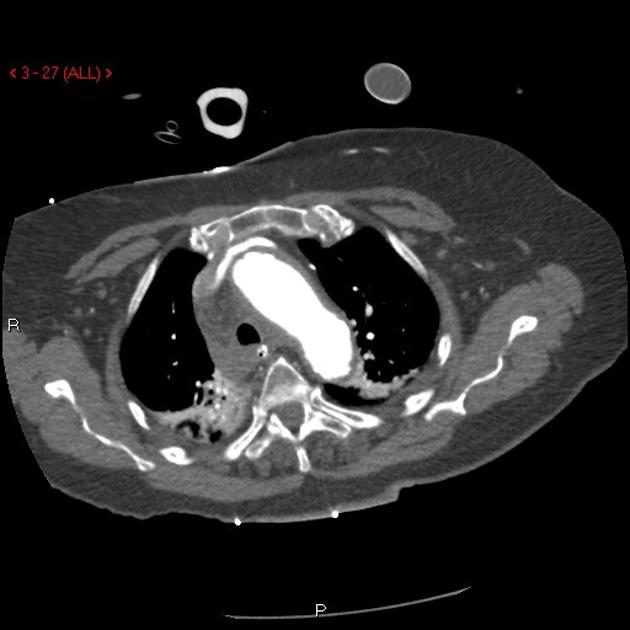

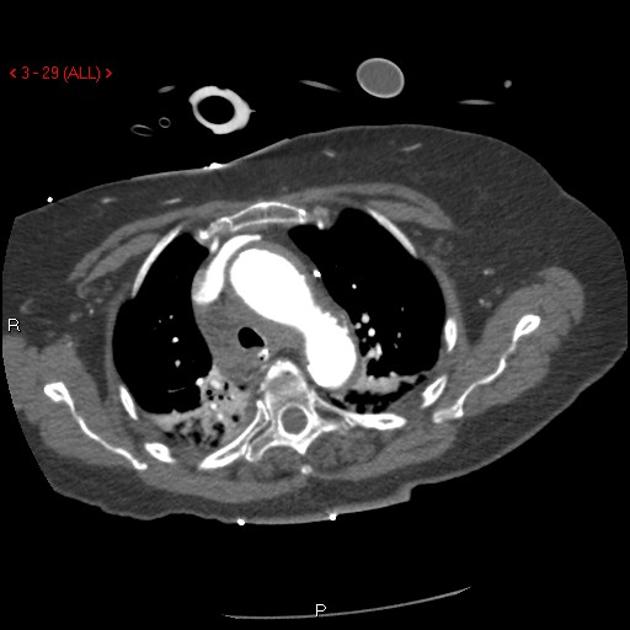

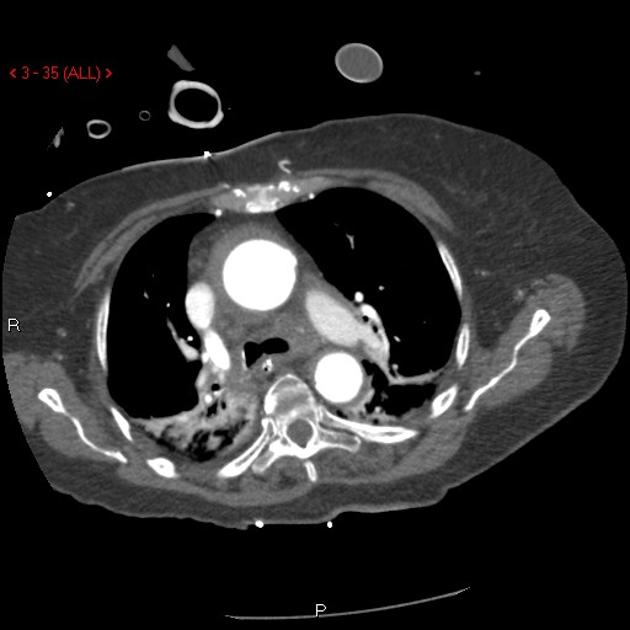

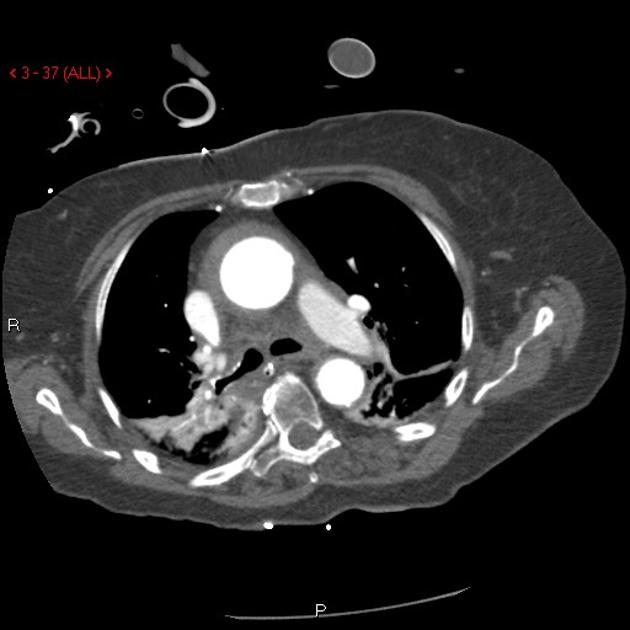

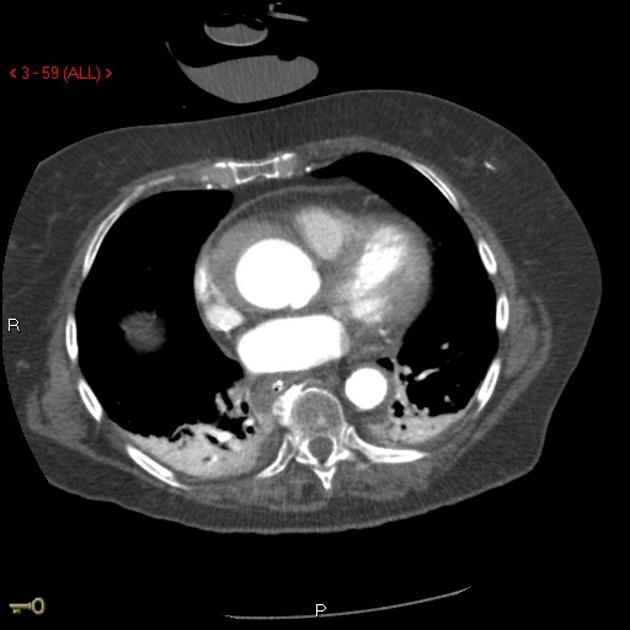

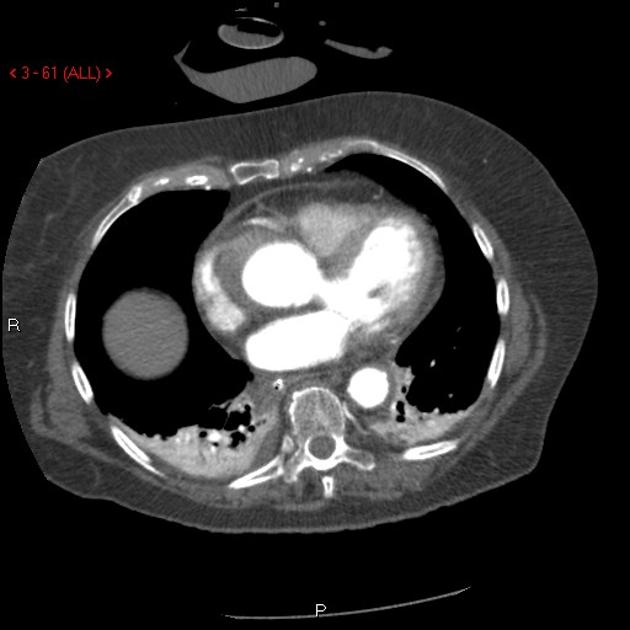

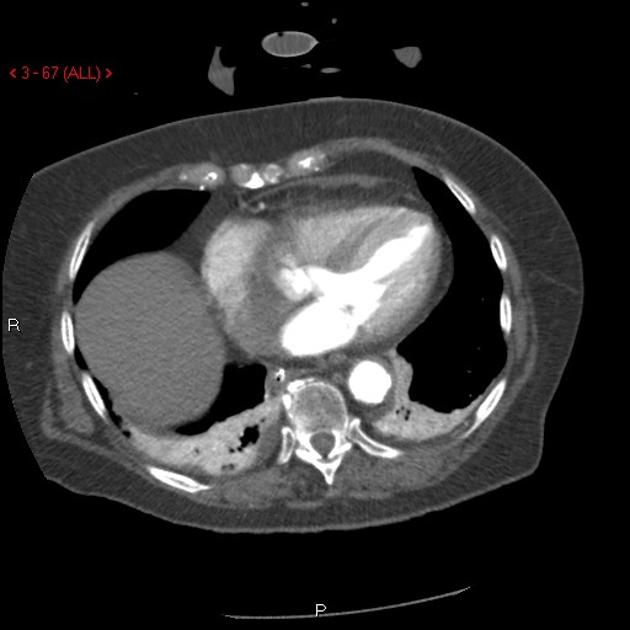

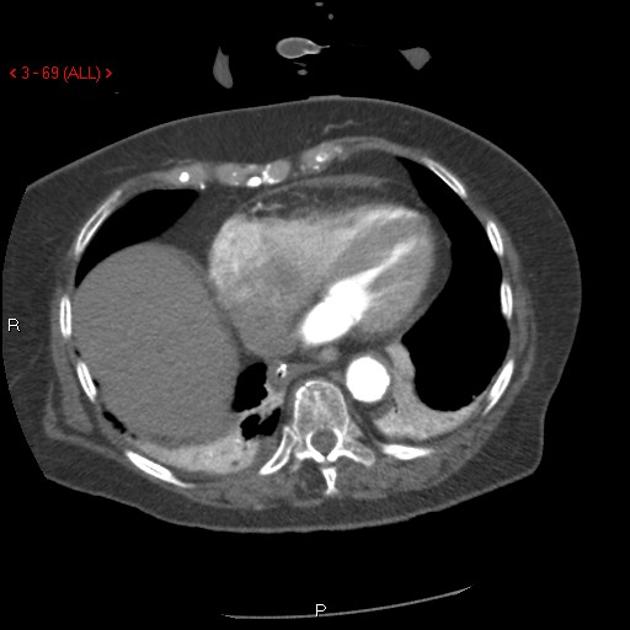

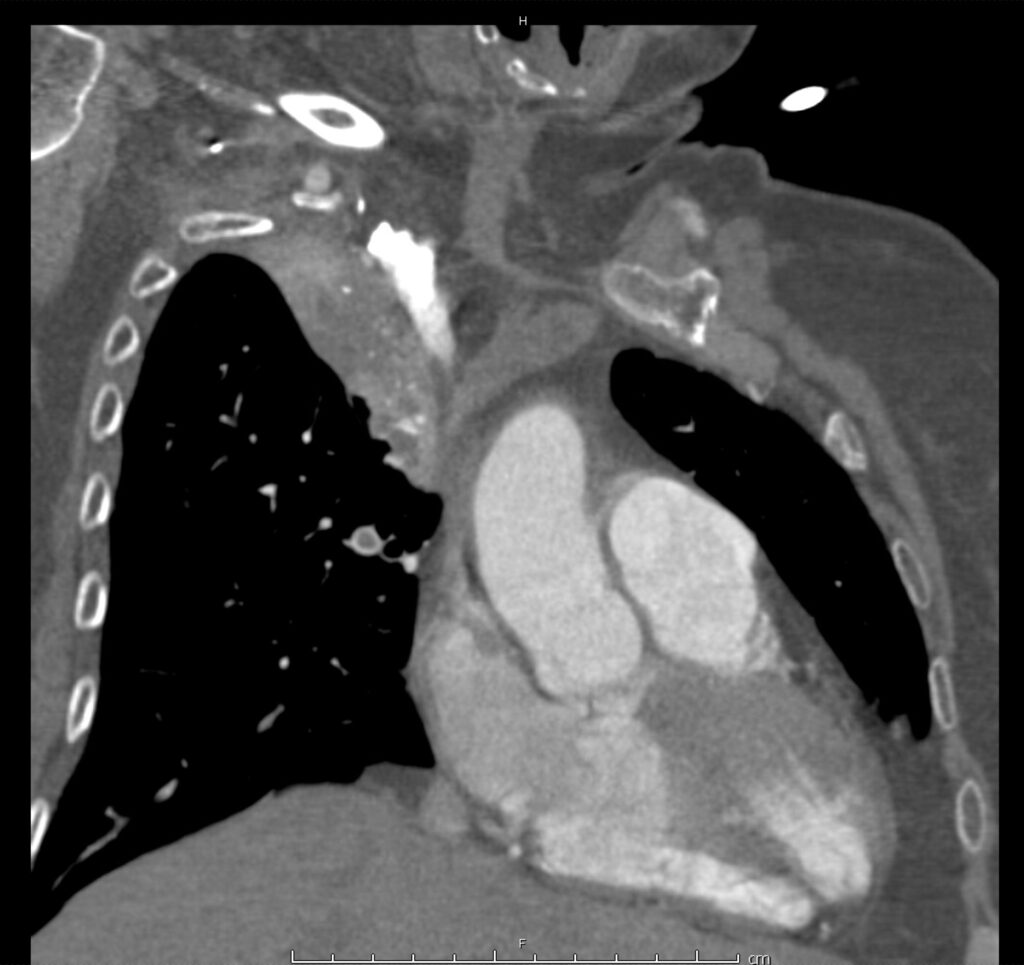

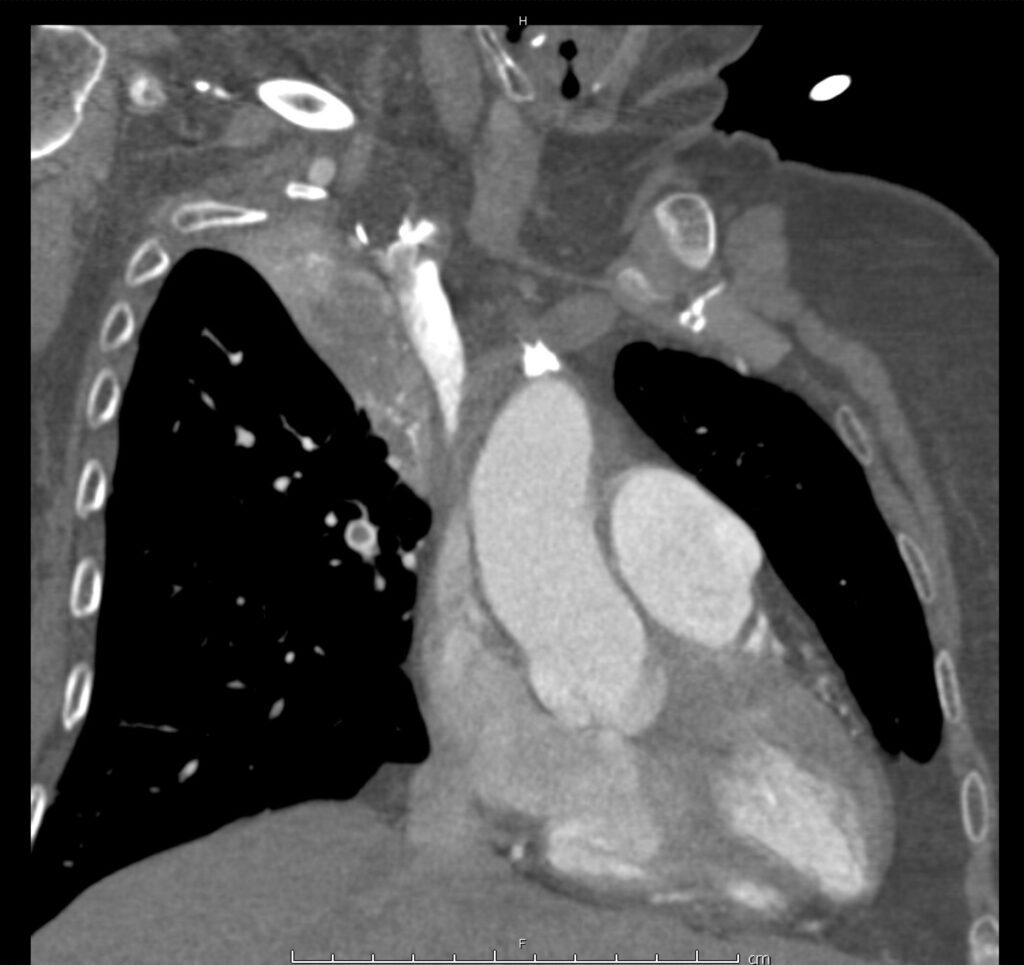

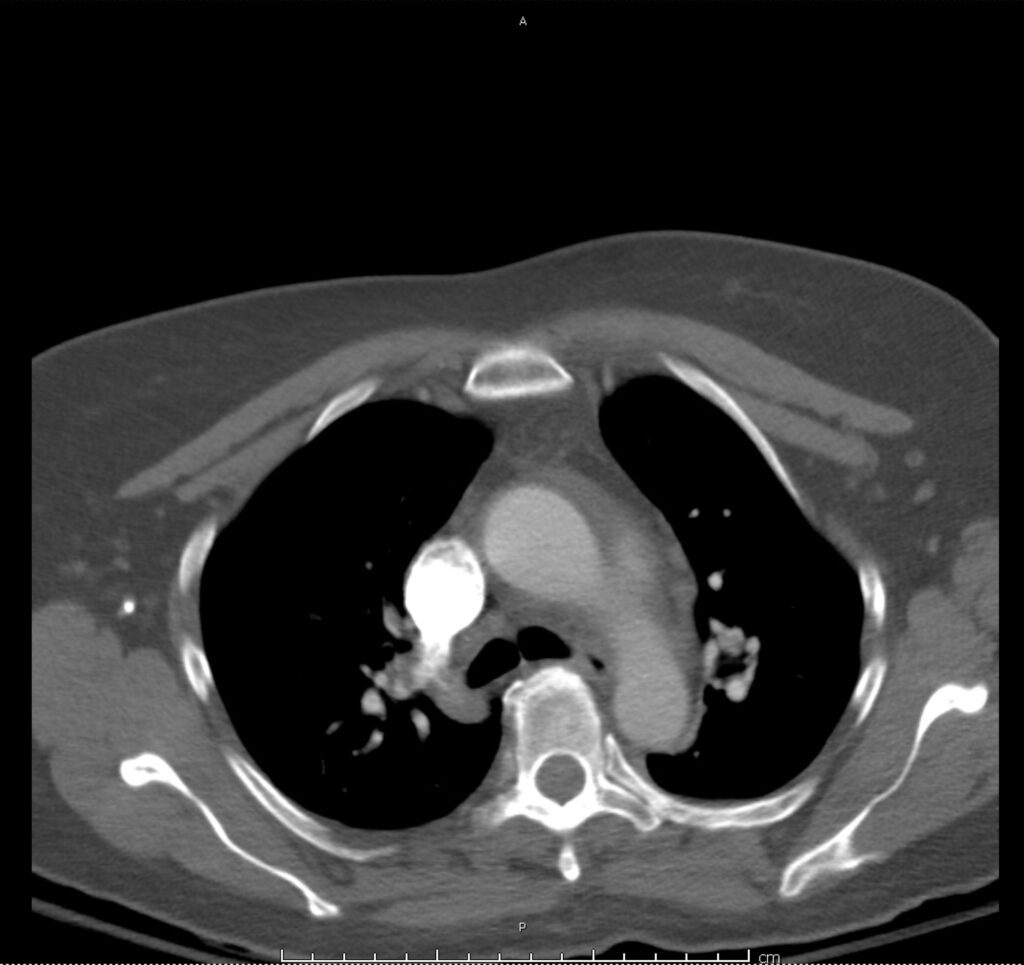

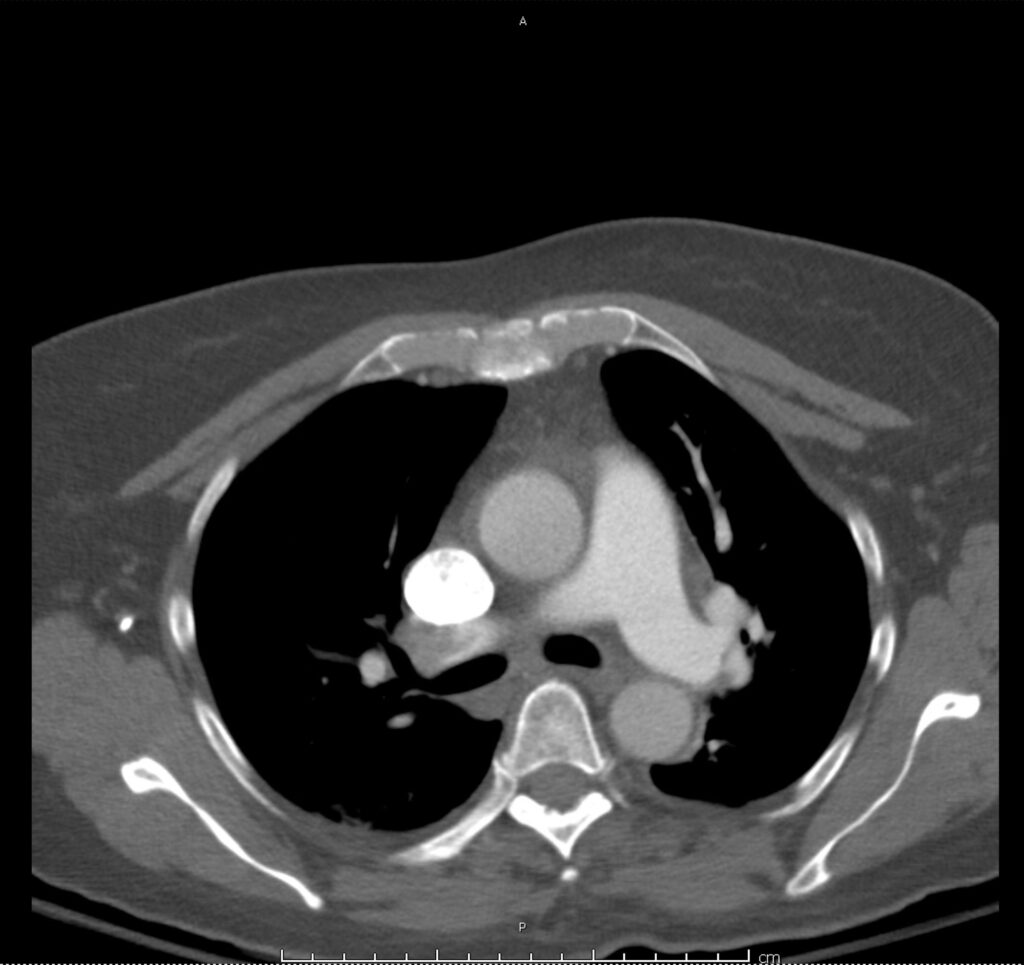

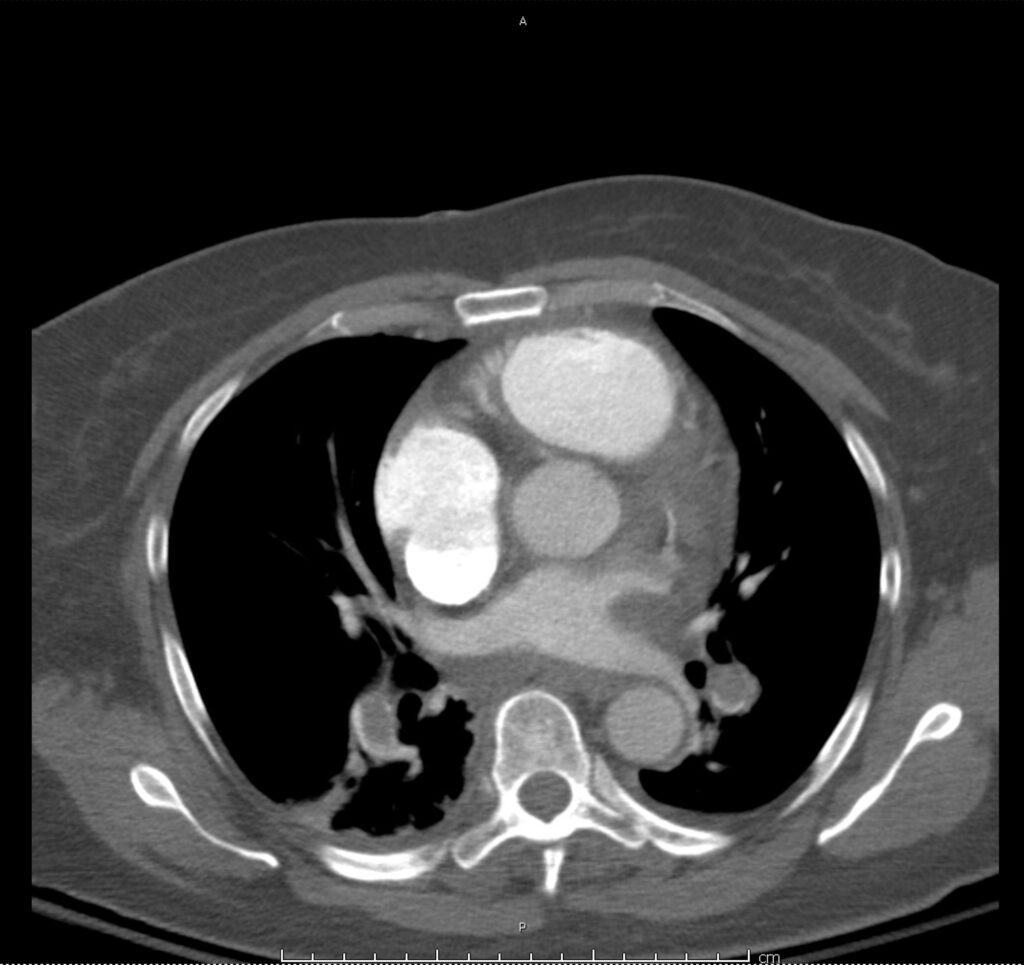

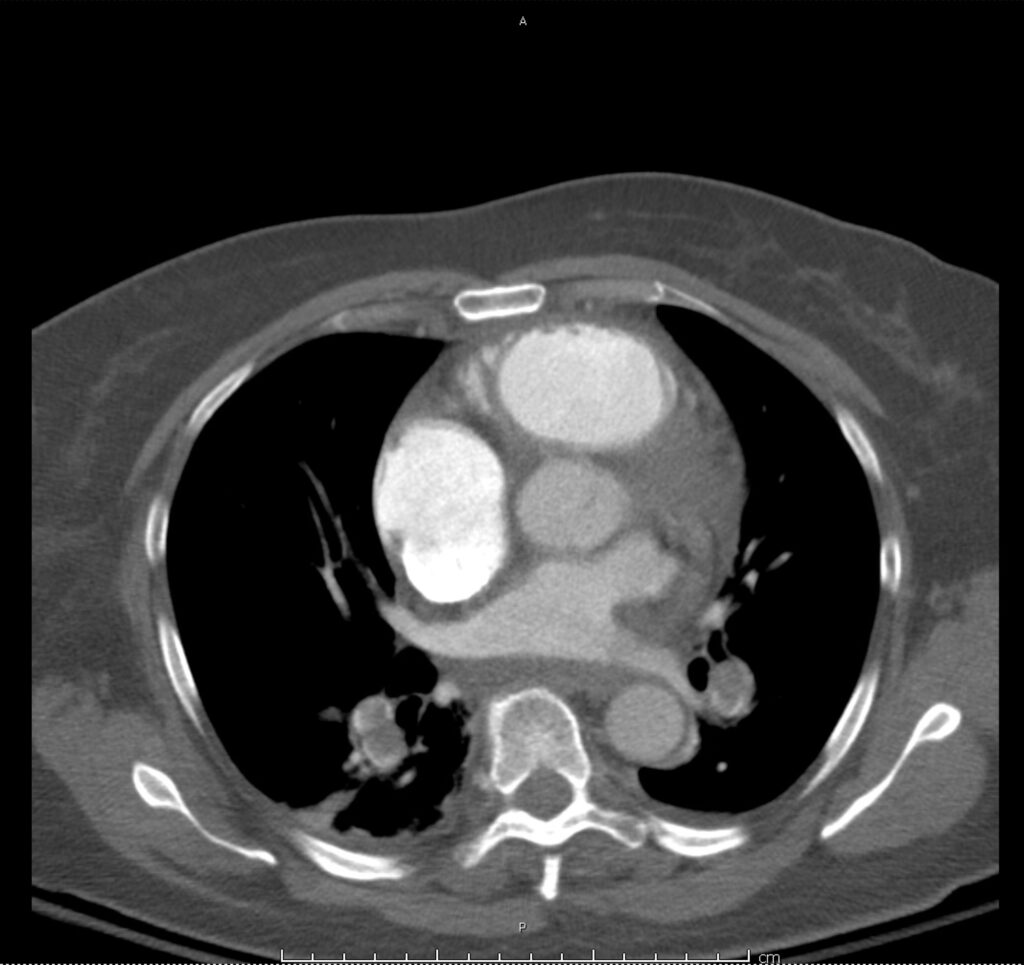

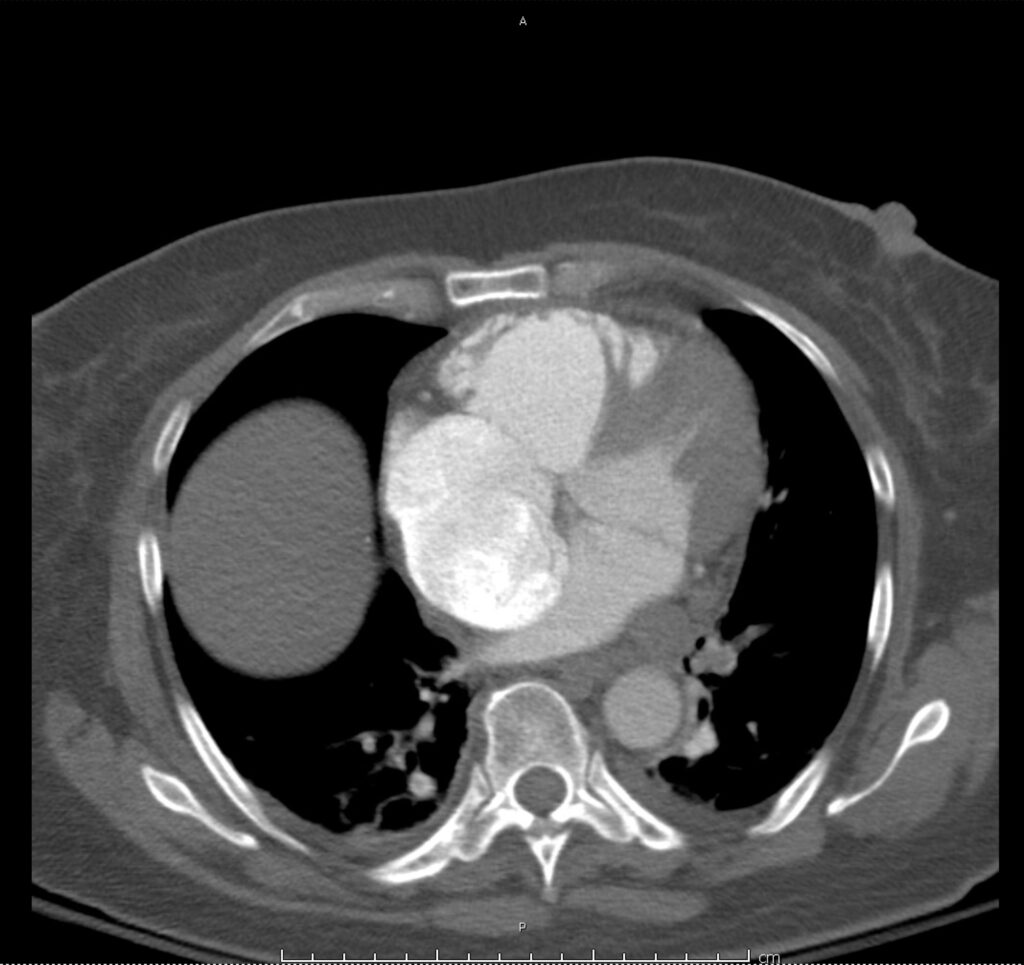

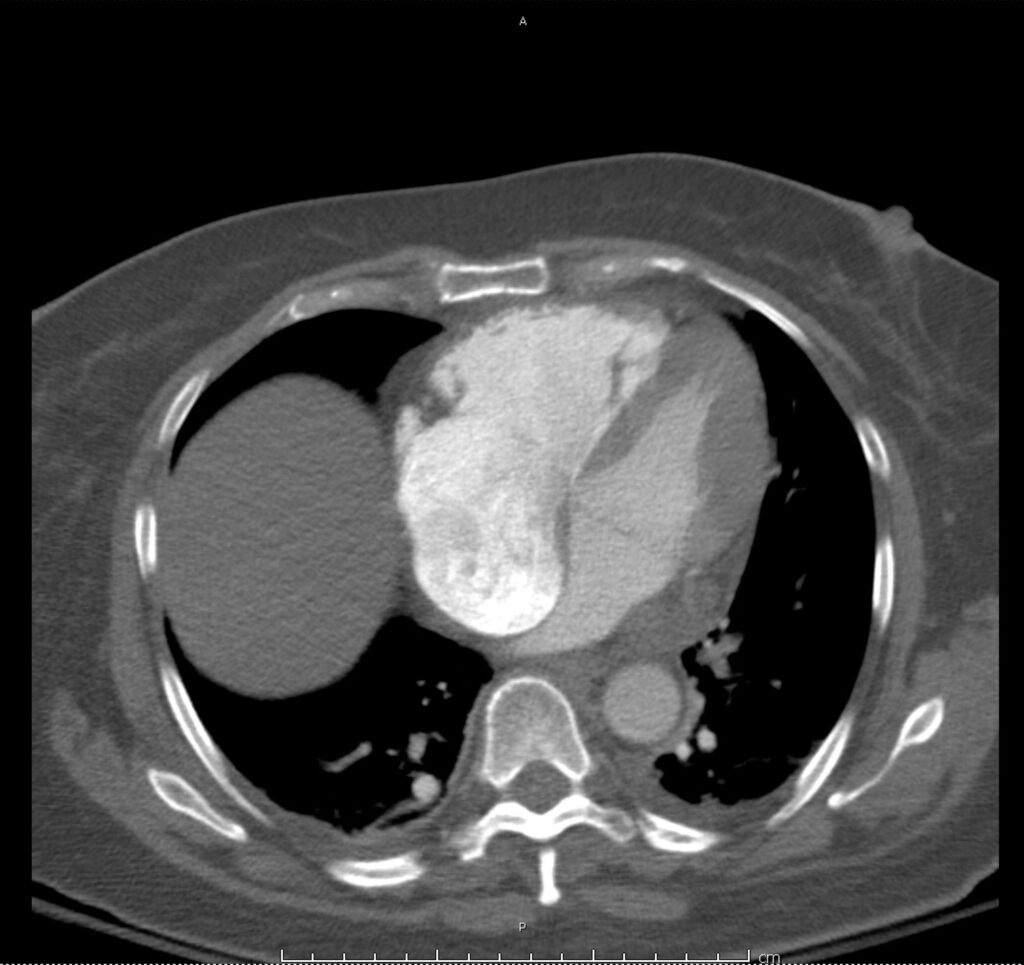

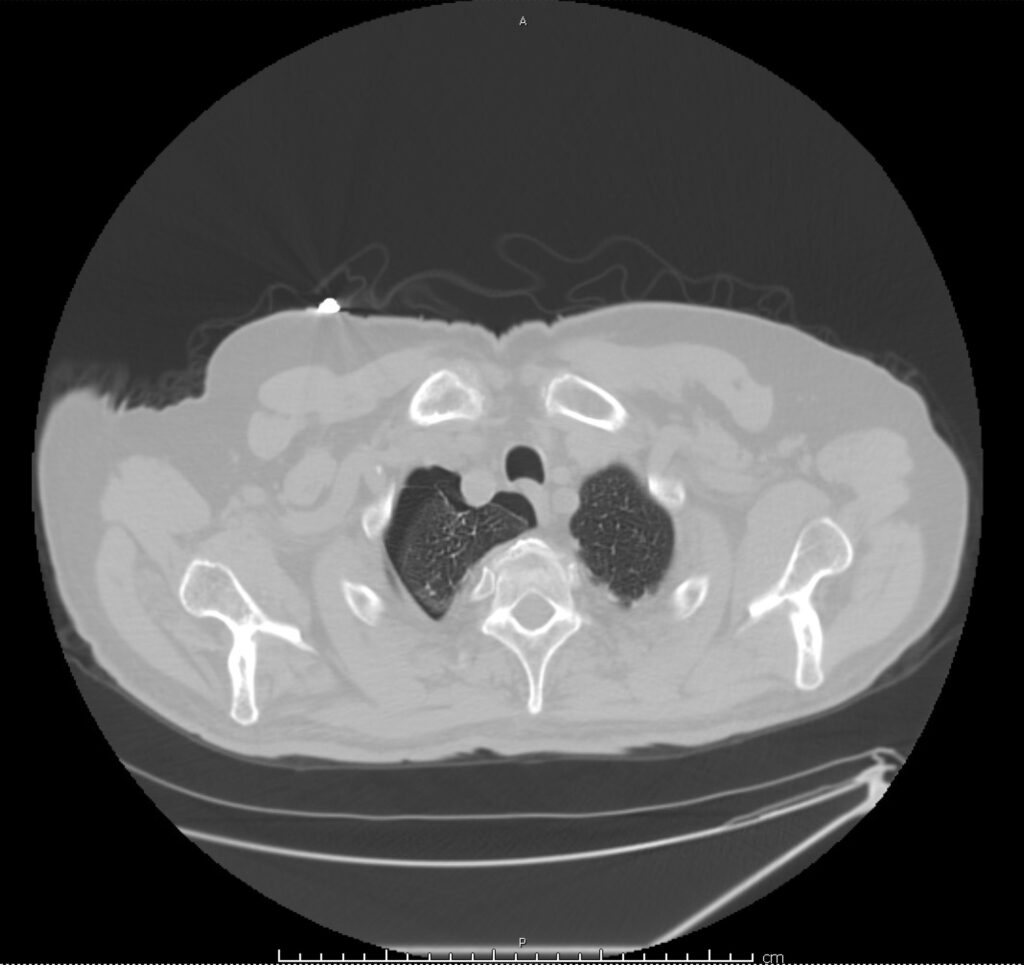

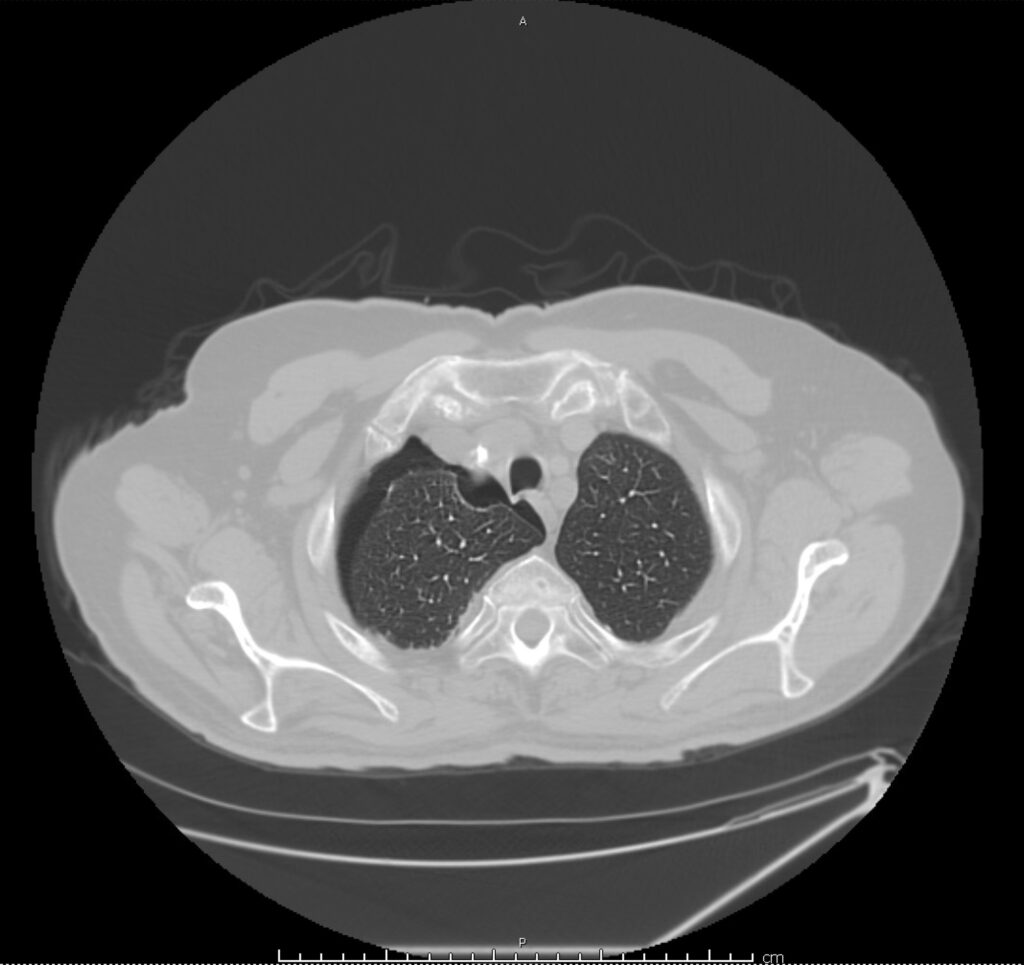

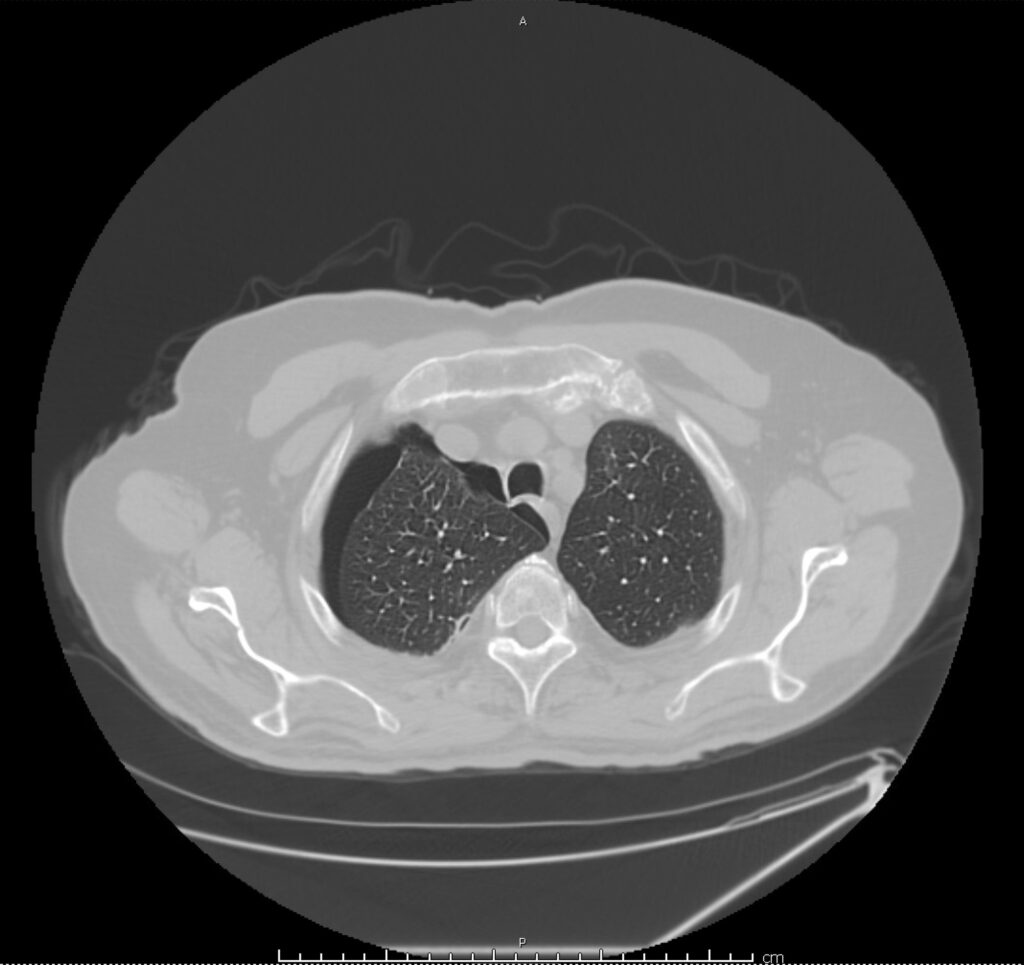

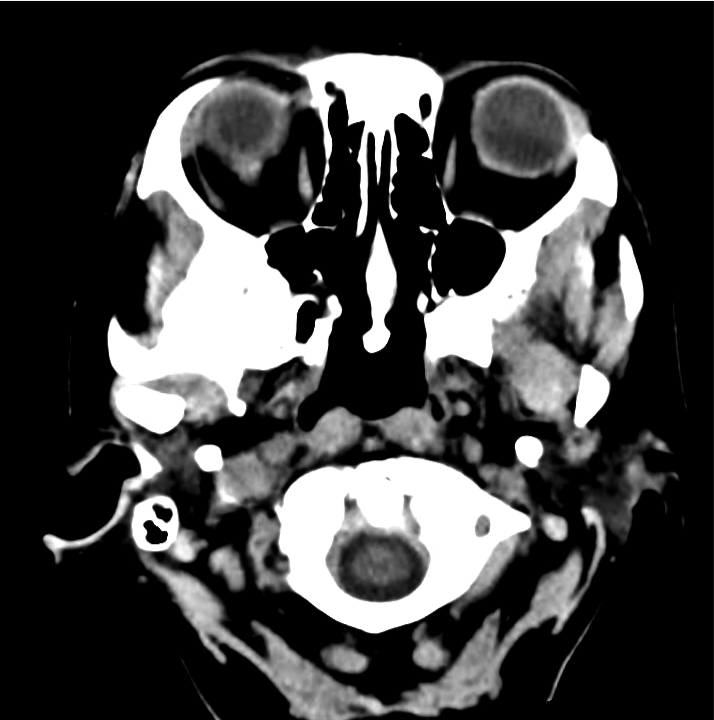

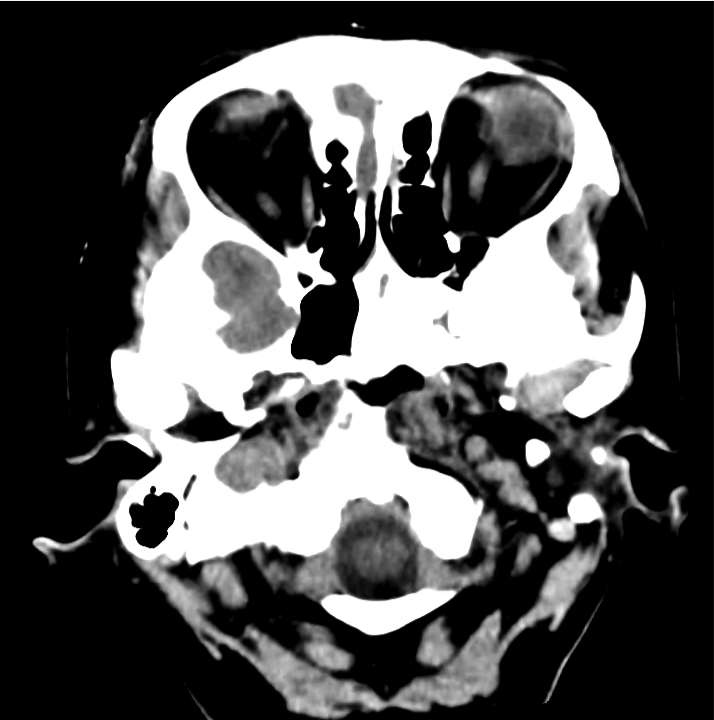

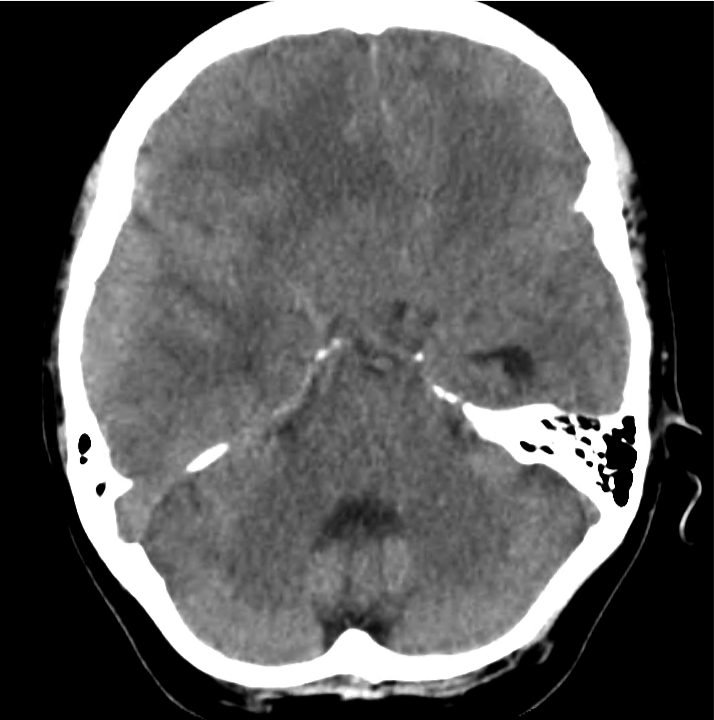

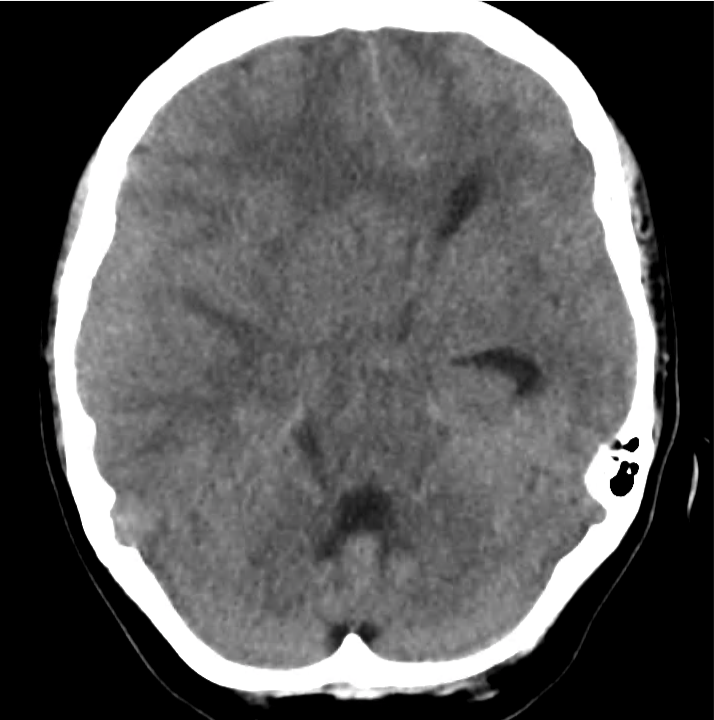

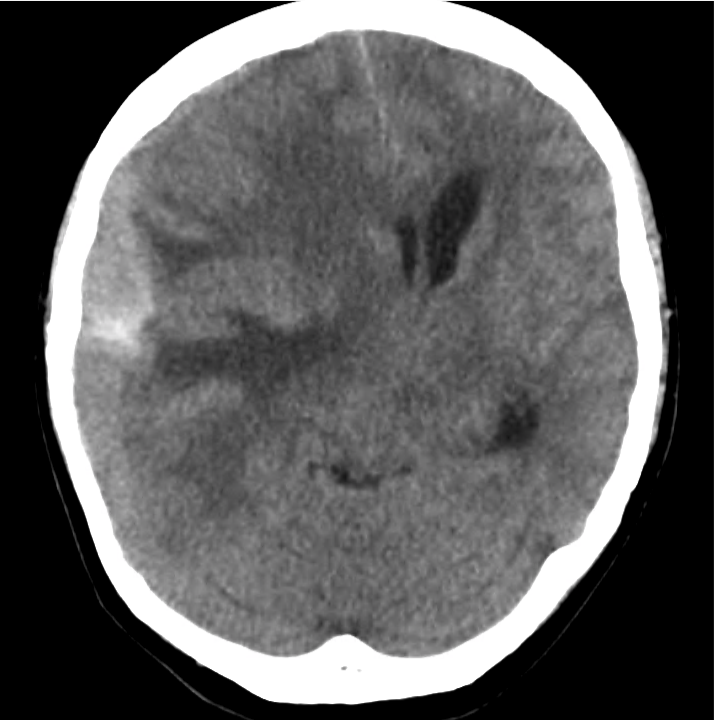

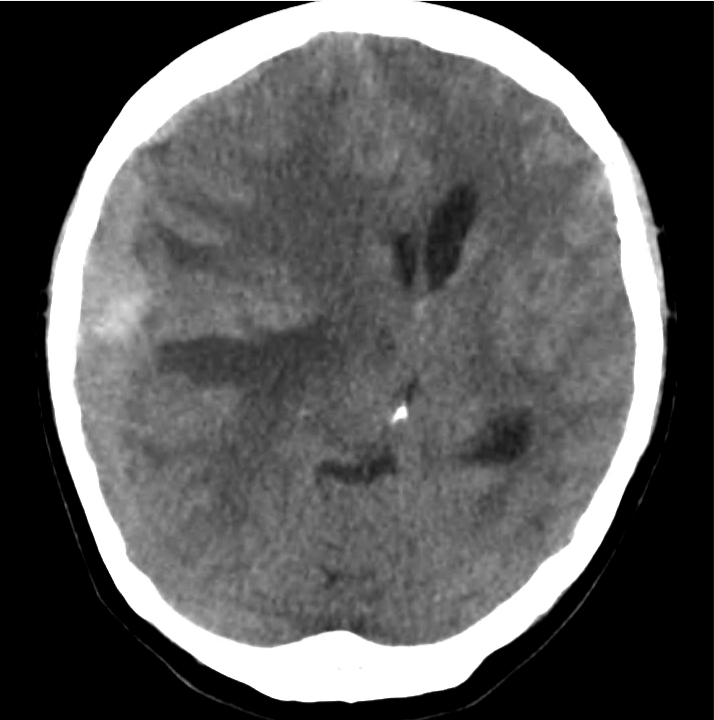

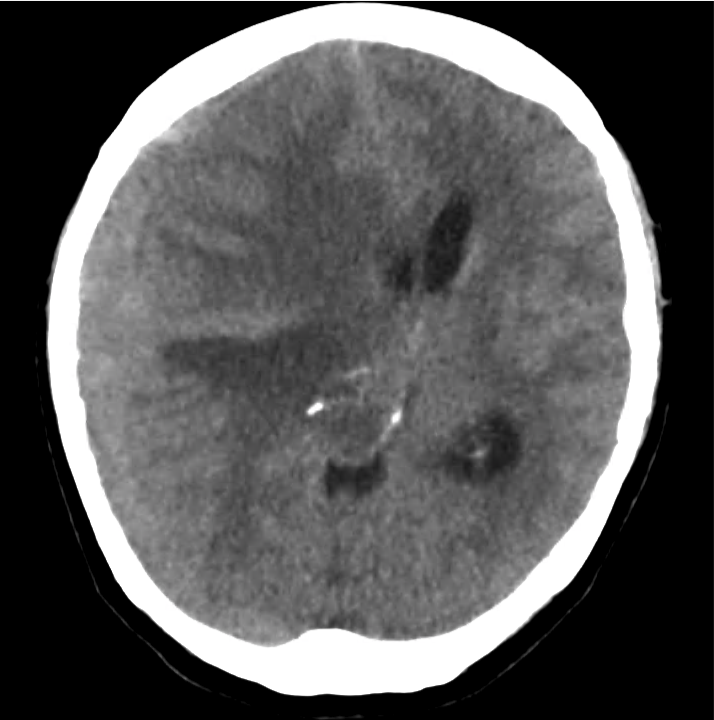

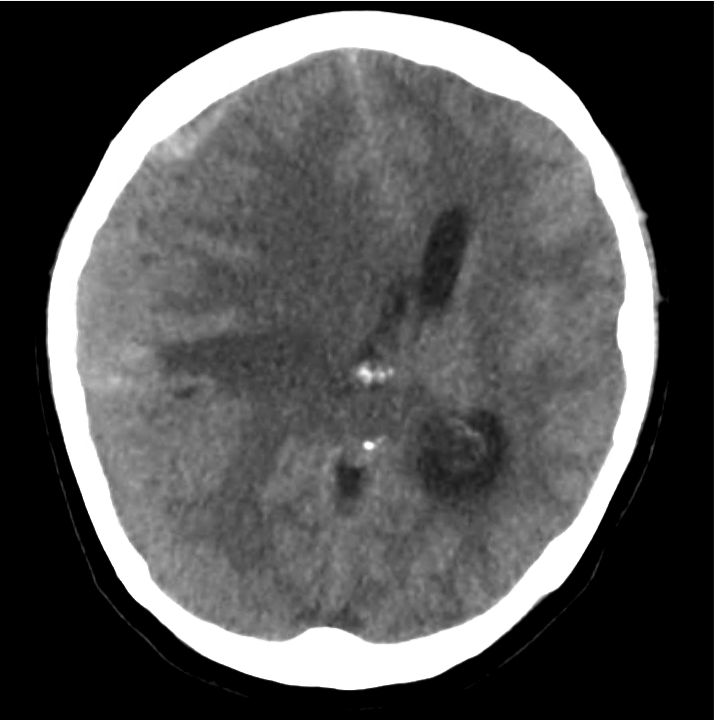

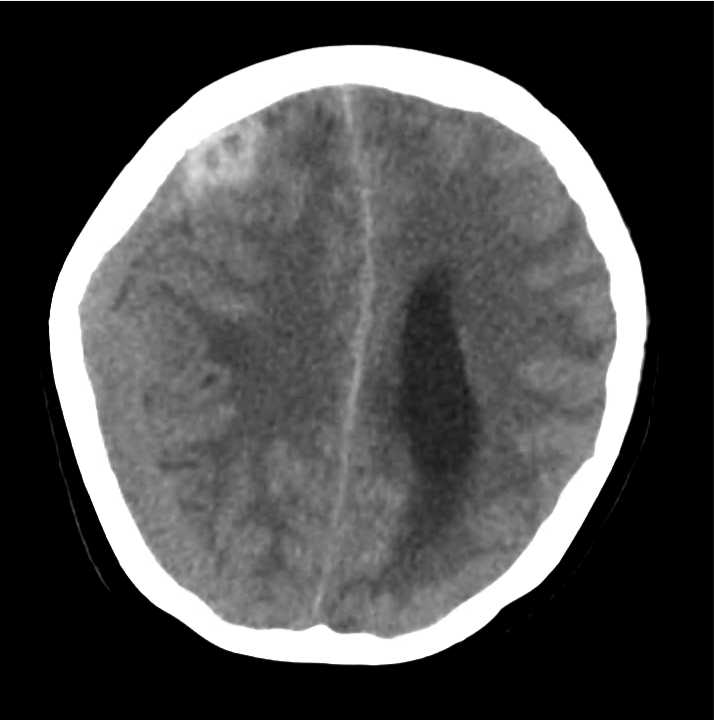

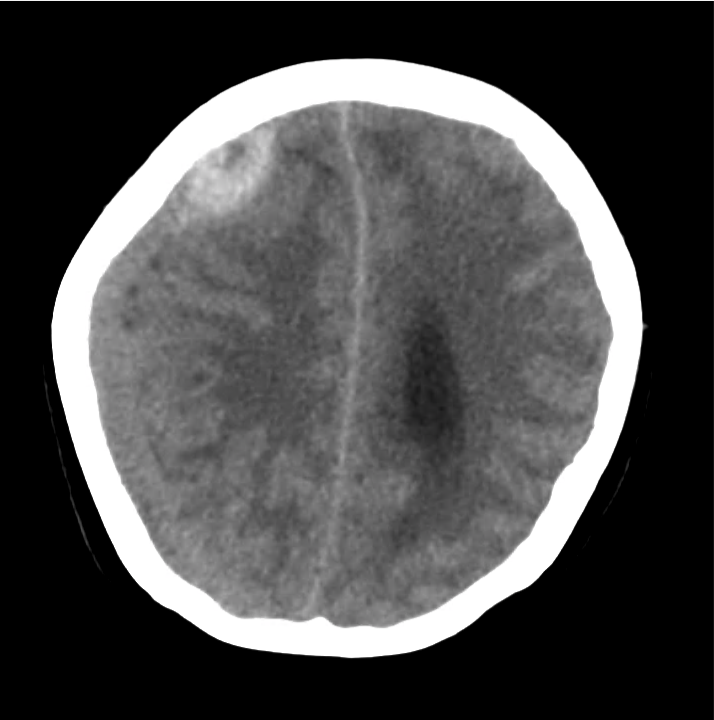

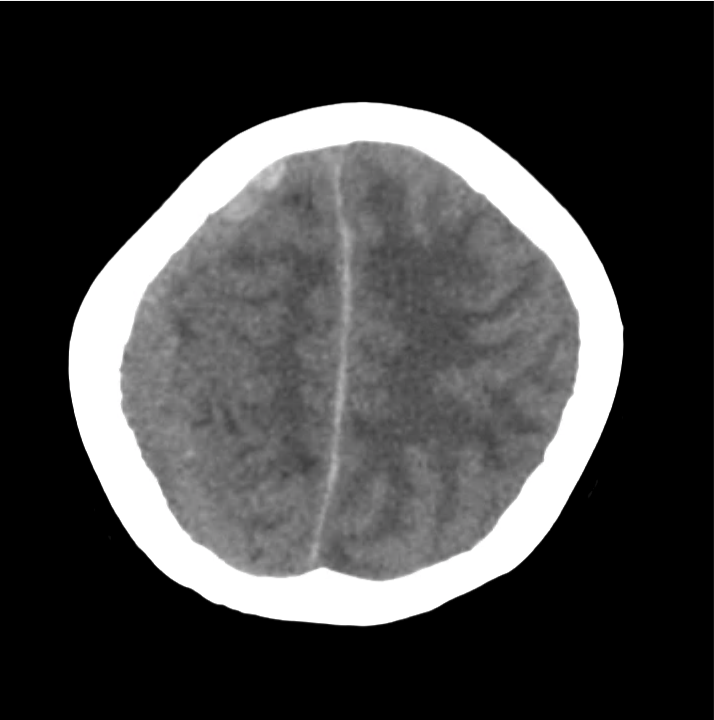

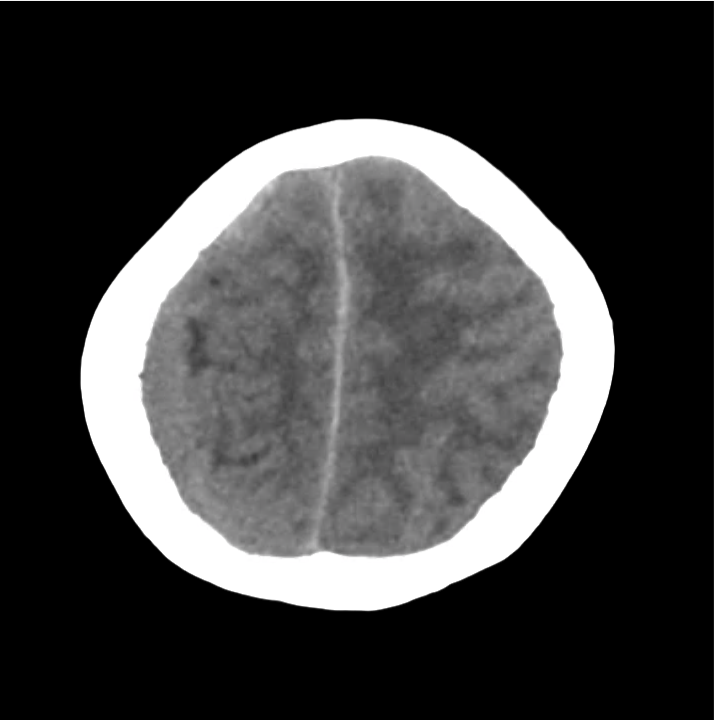

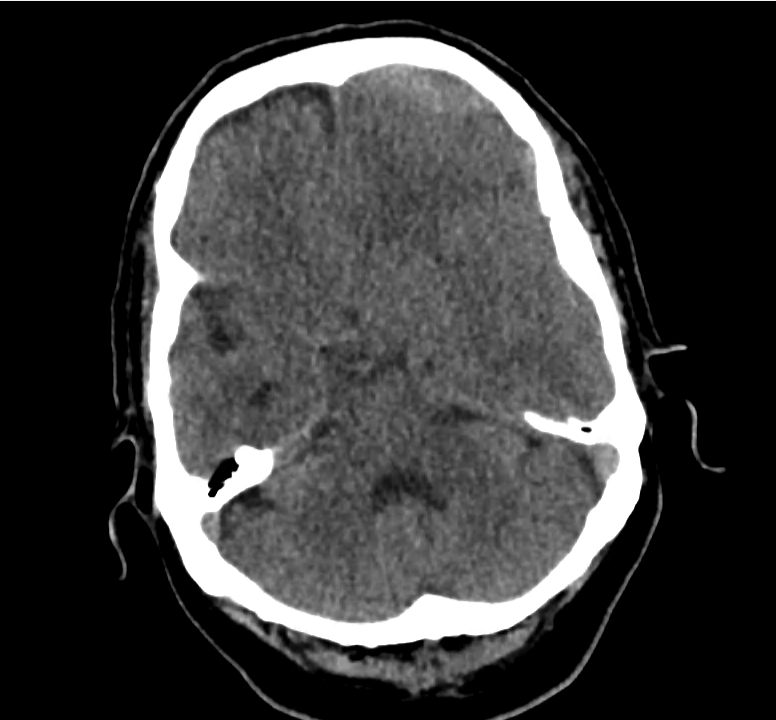

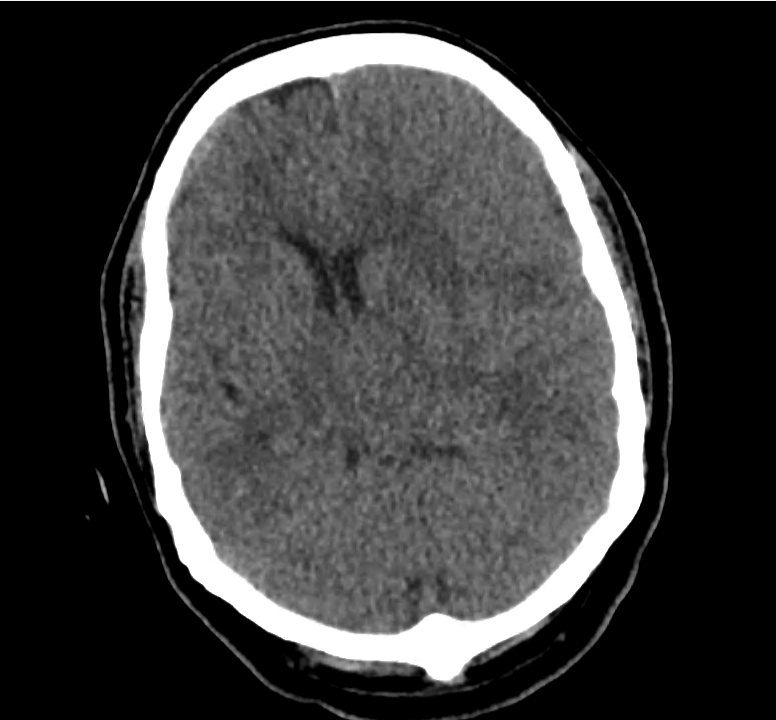

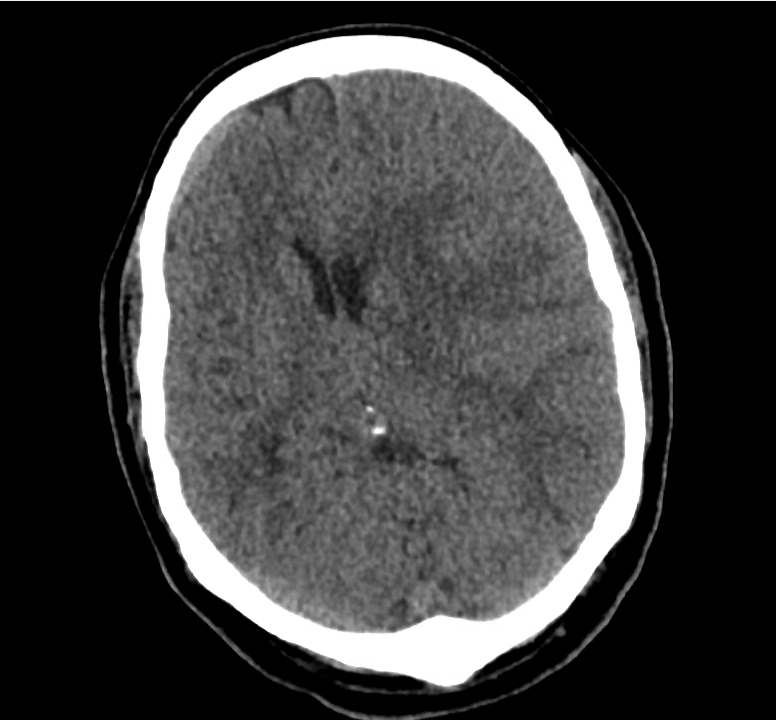

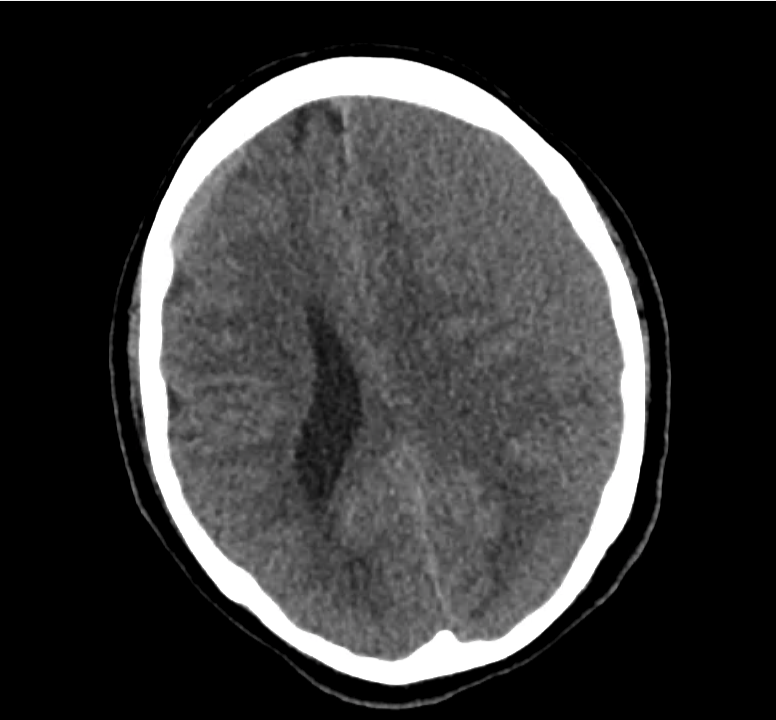

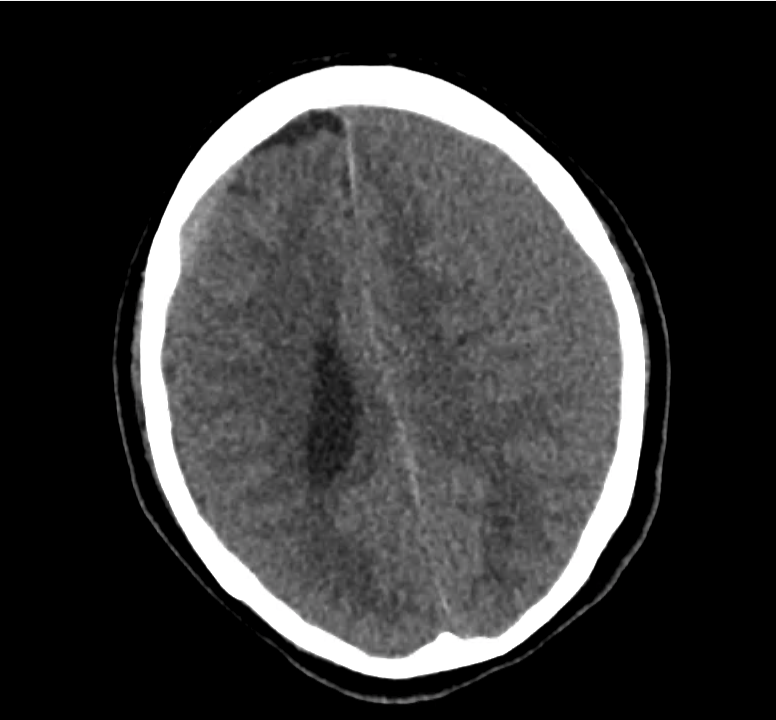

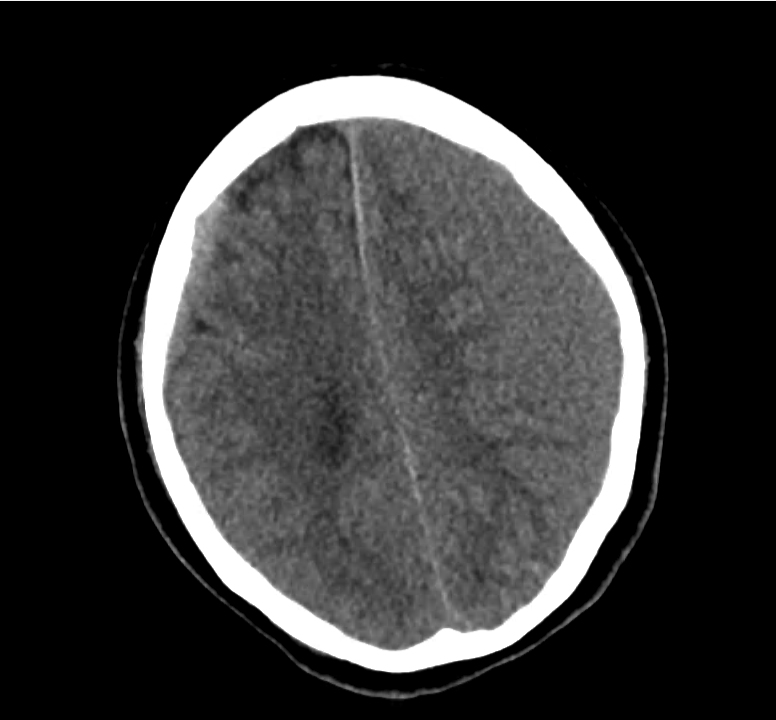

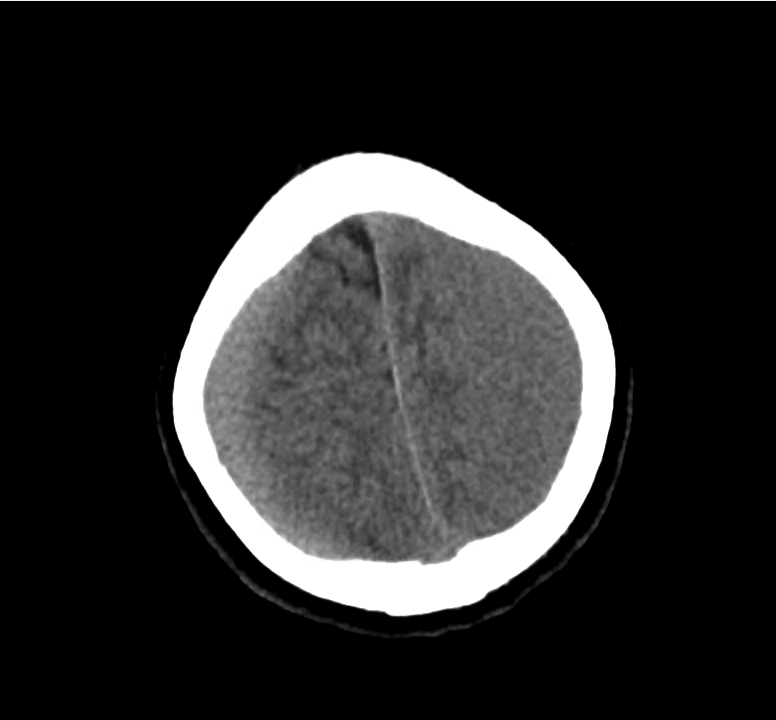

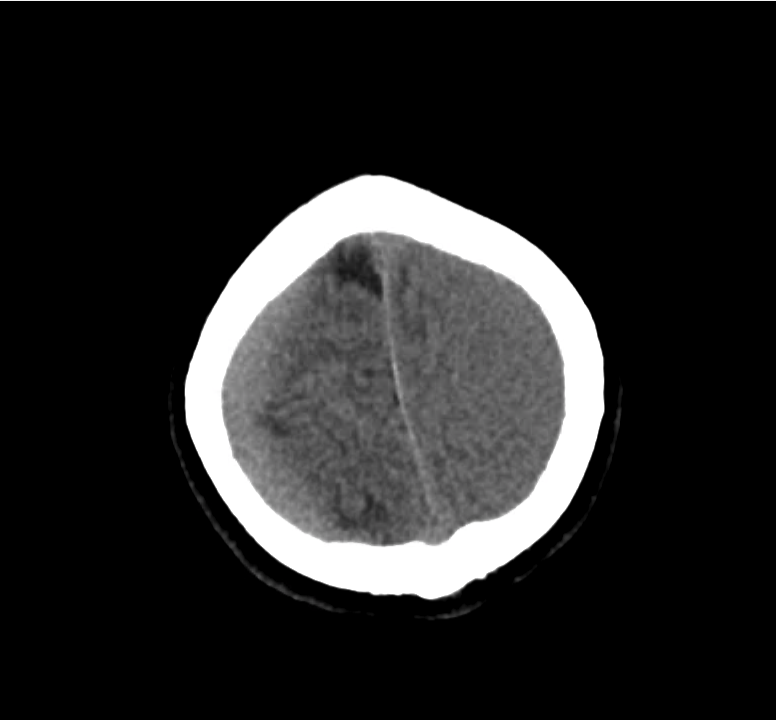

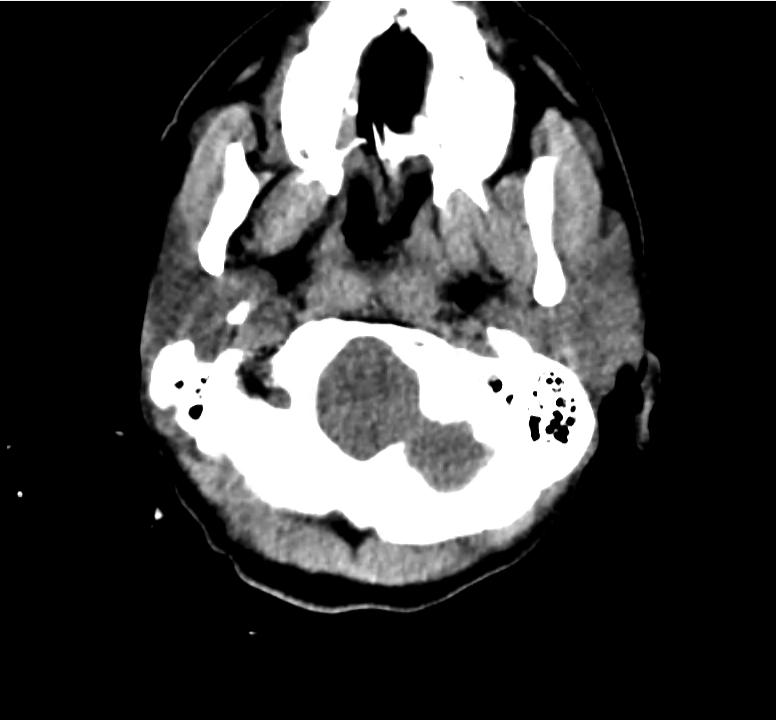

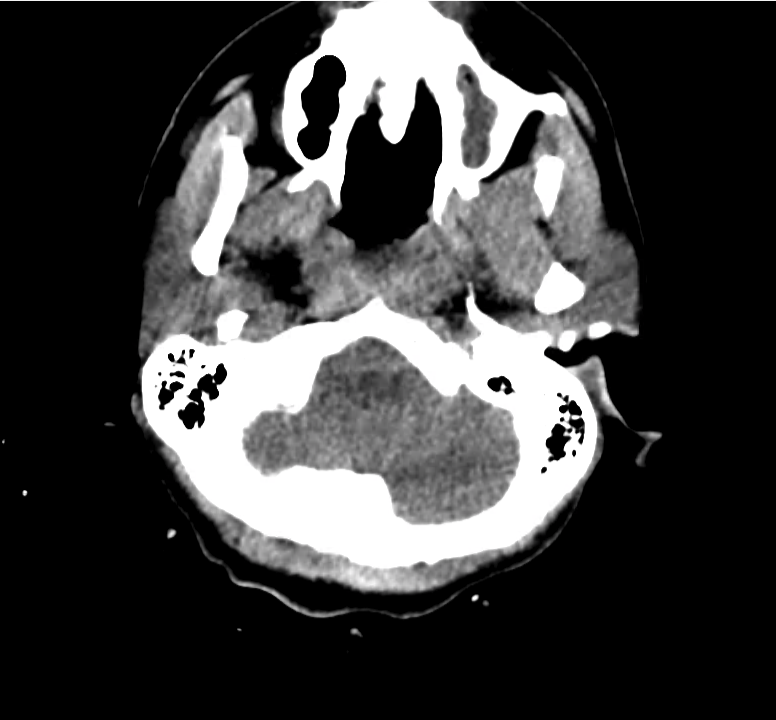

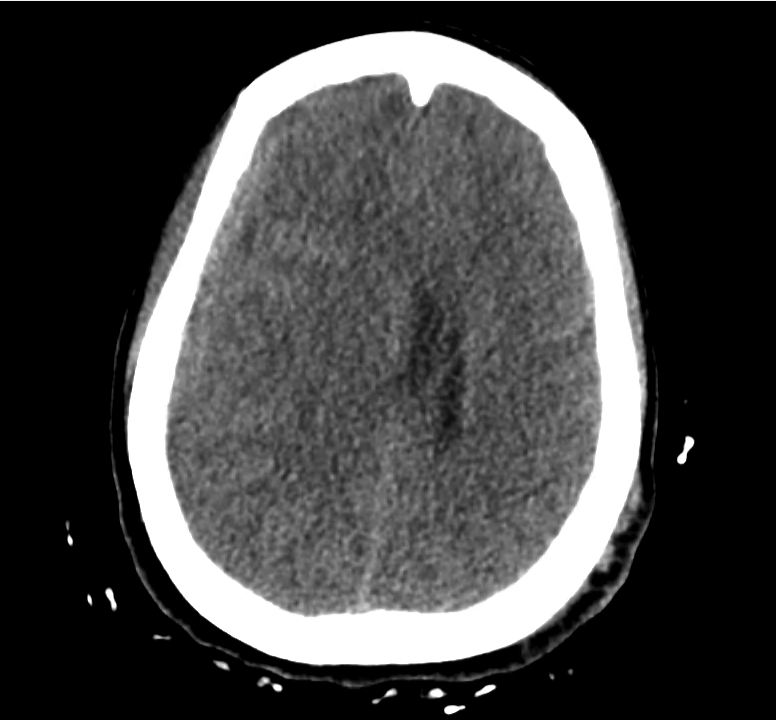

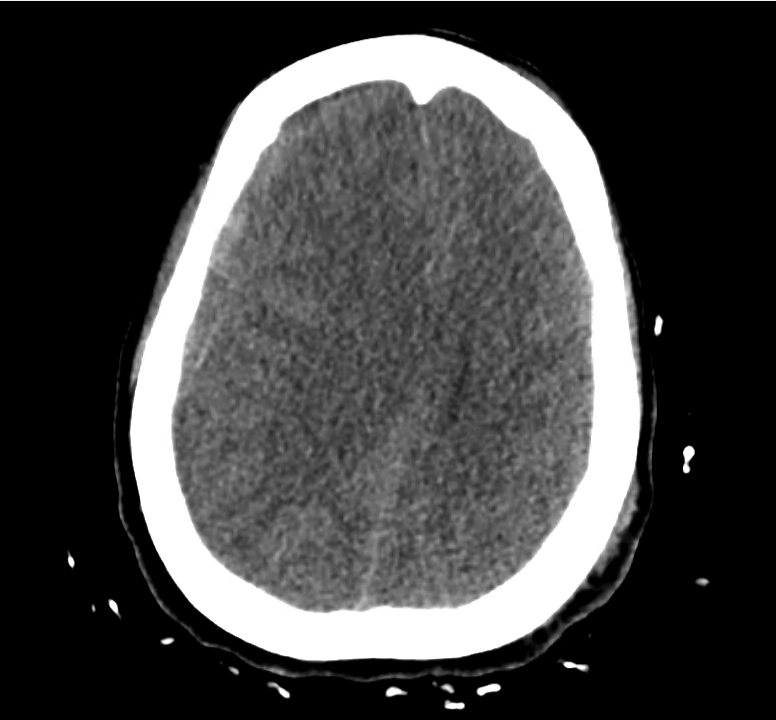

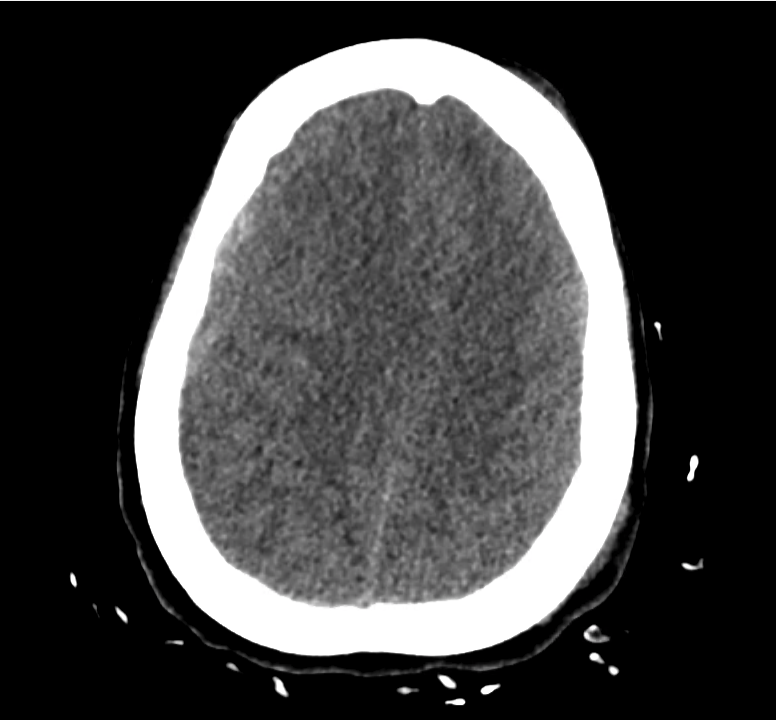

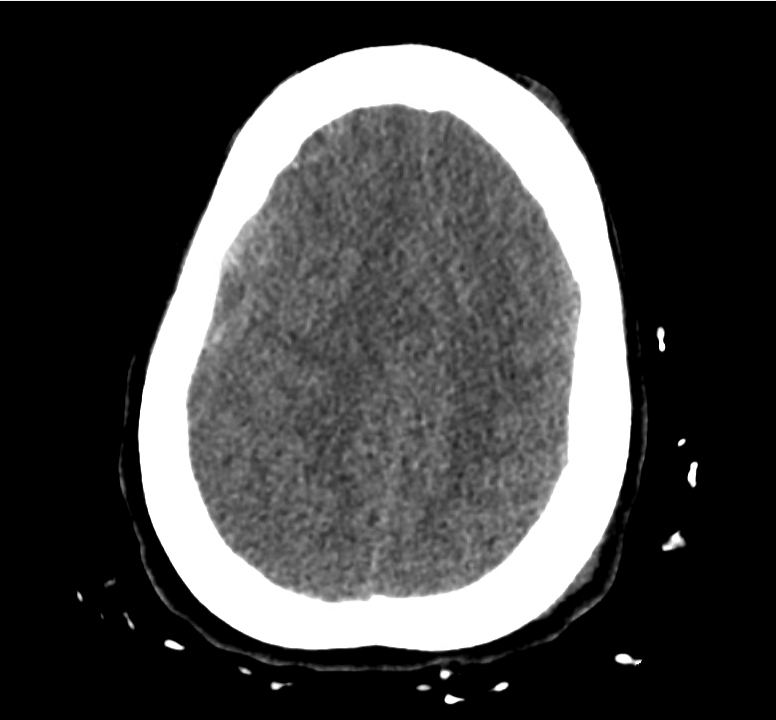

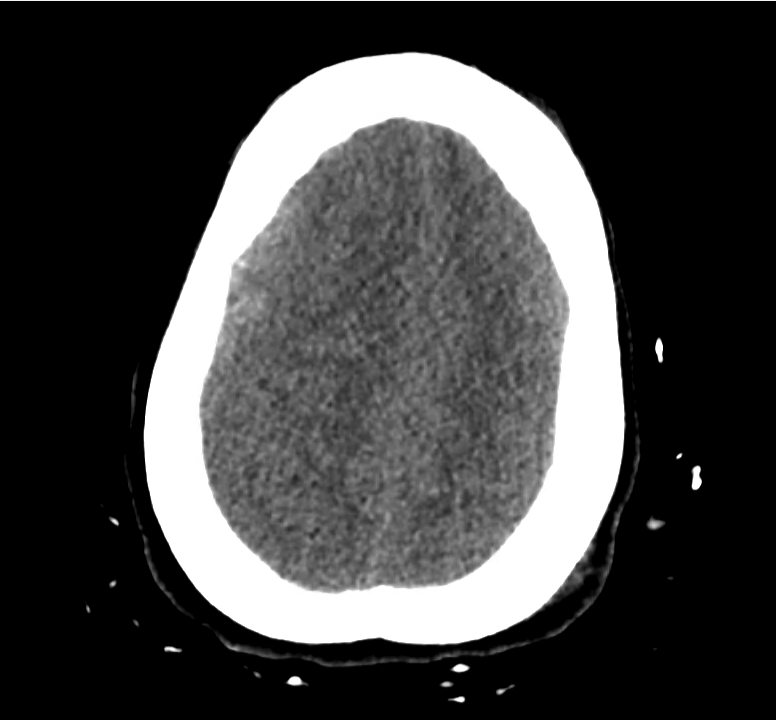

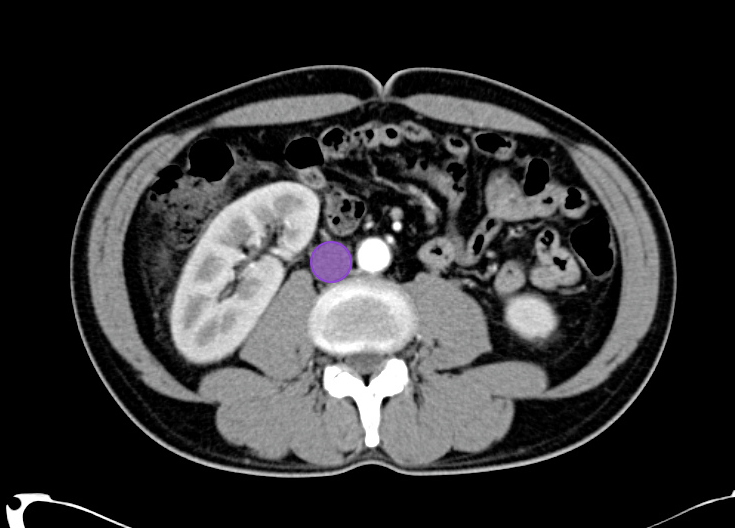

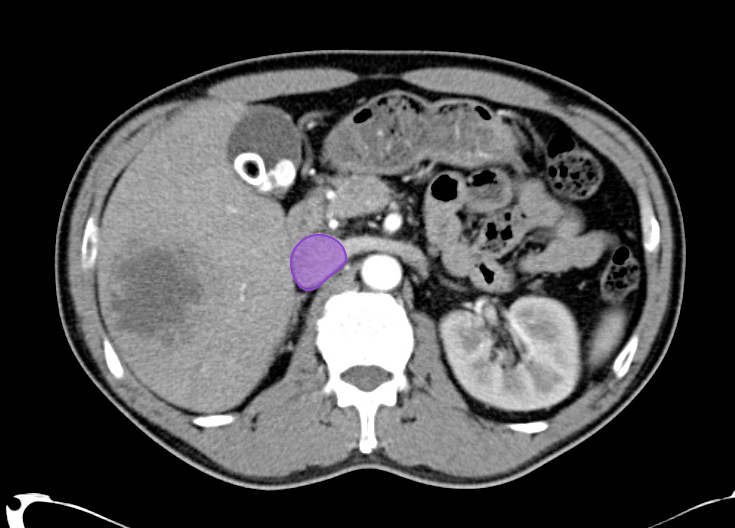

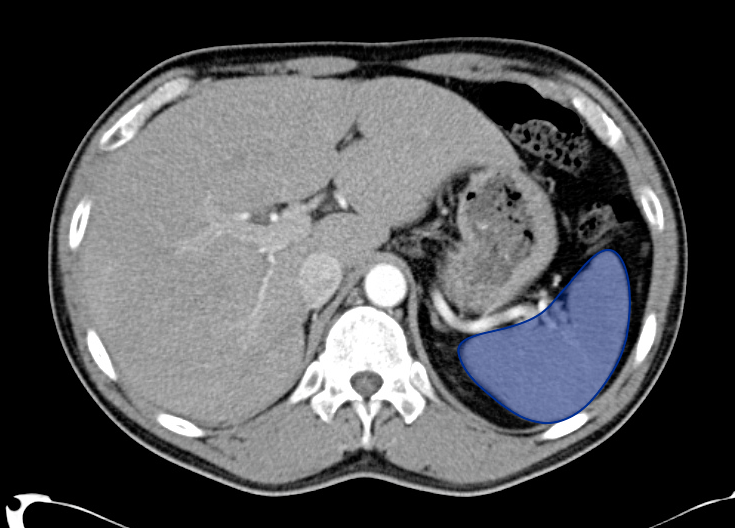

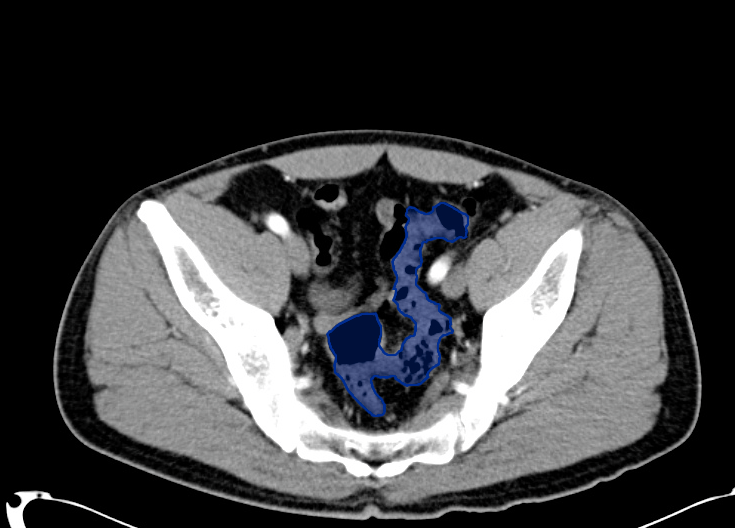

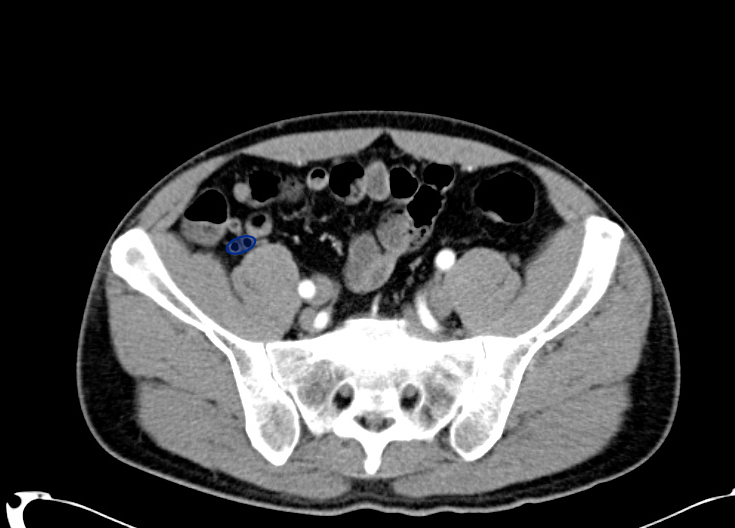

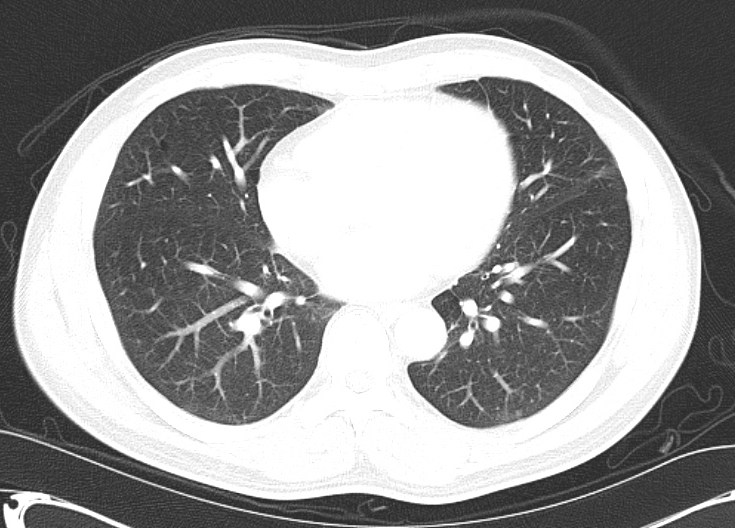

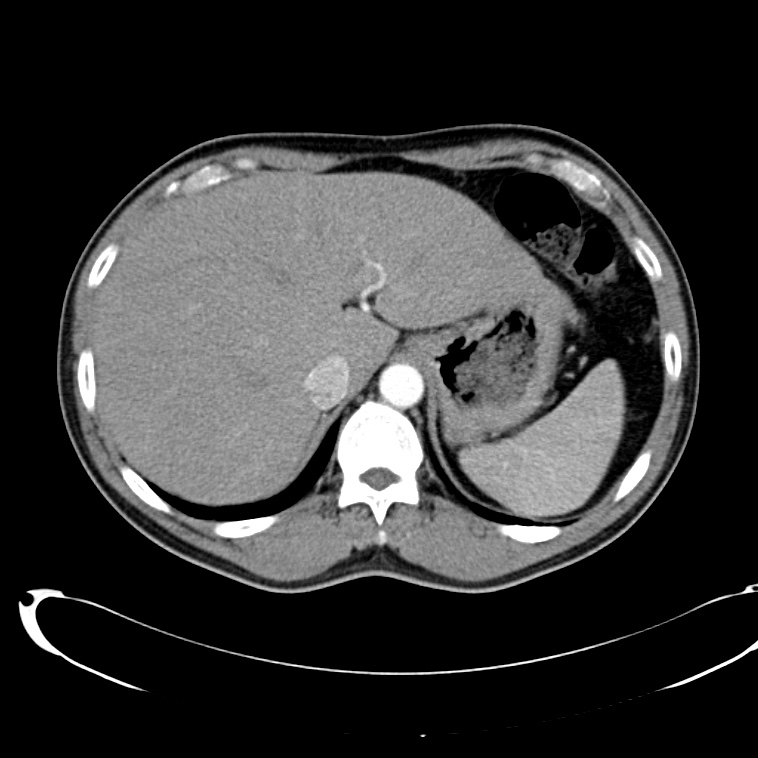

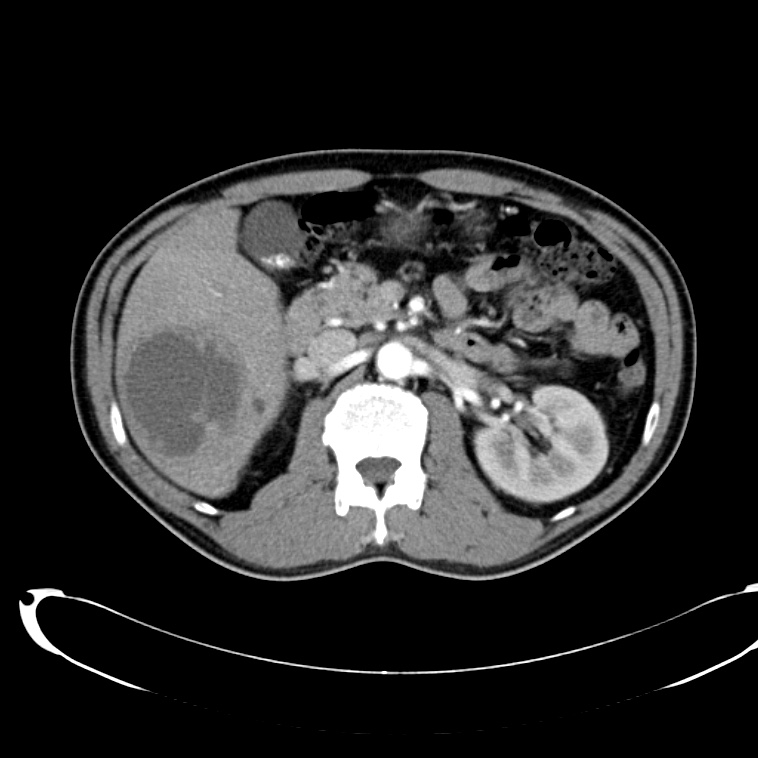

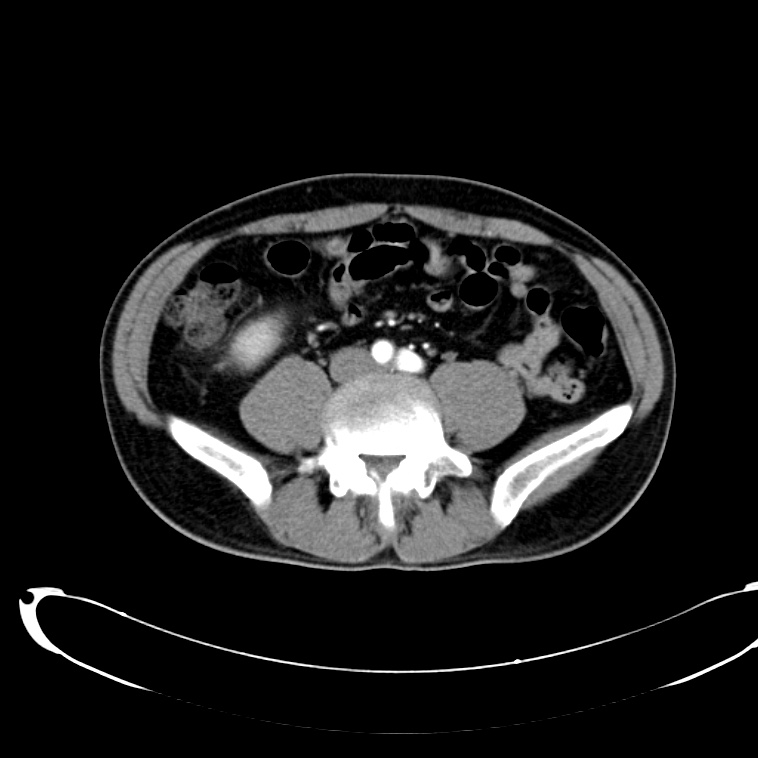

Example #2

CT Head Interpretation

- Bilateral subacute subdural hematomas, left larger than right and associated with rightward midline shift.

- Left lateral ventricle is partially effaced.

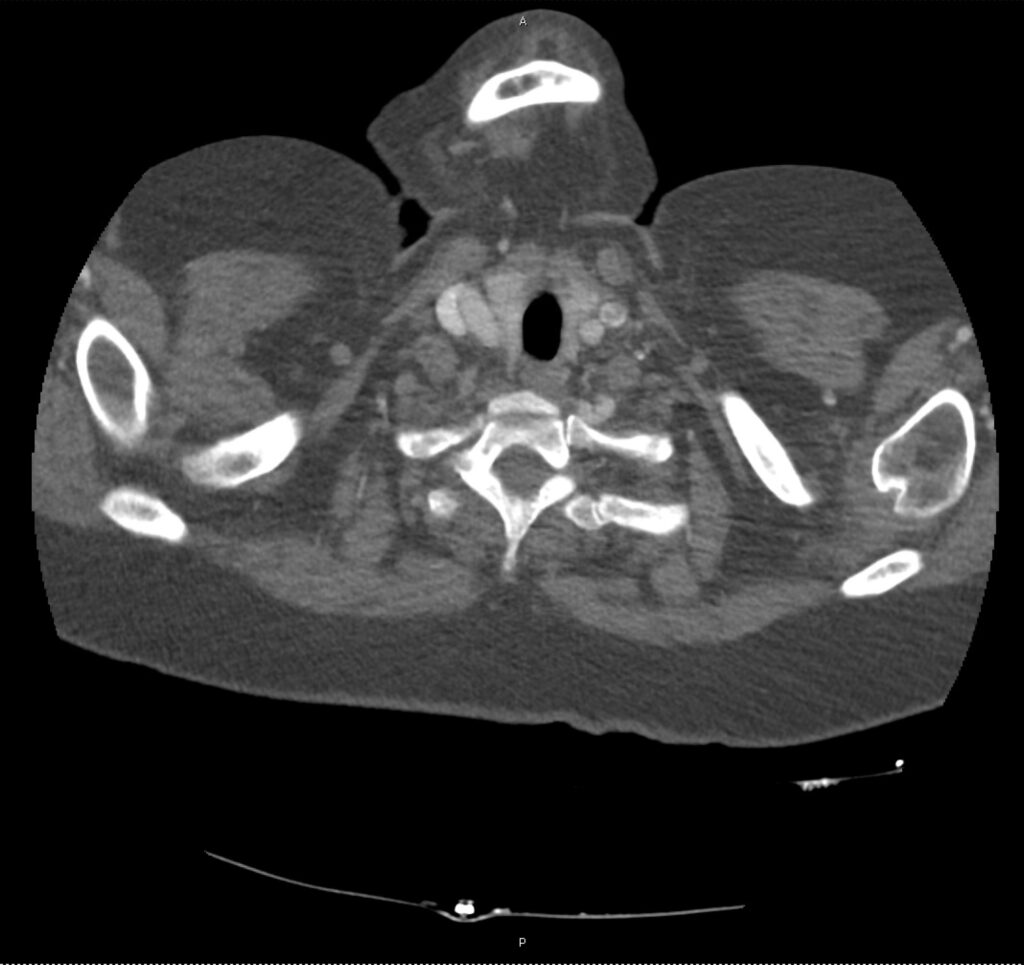

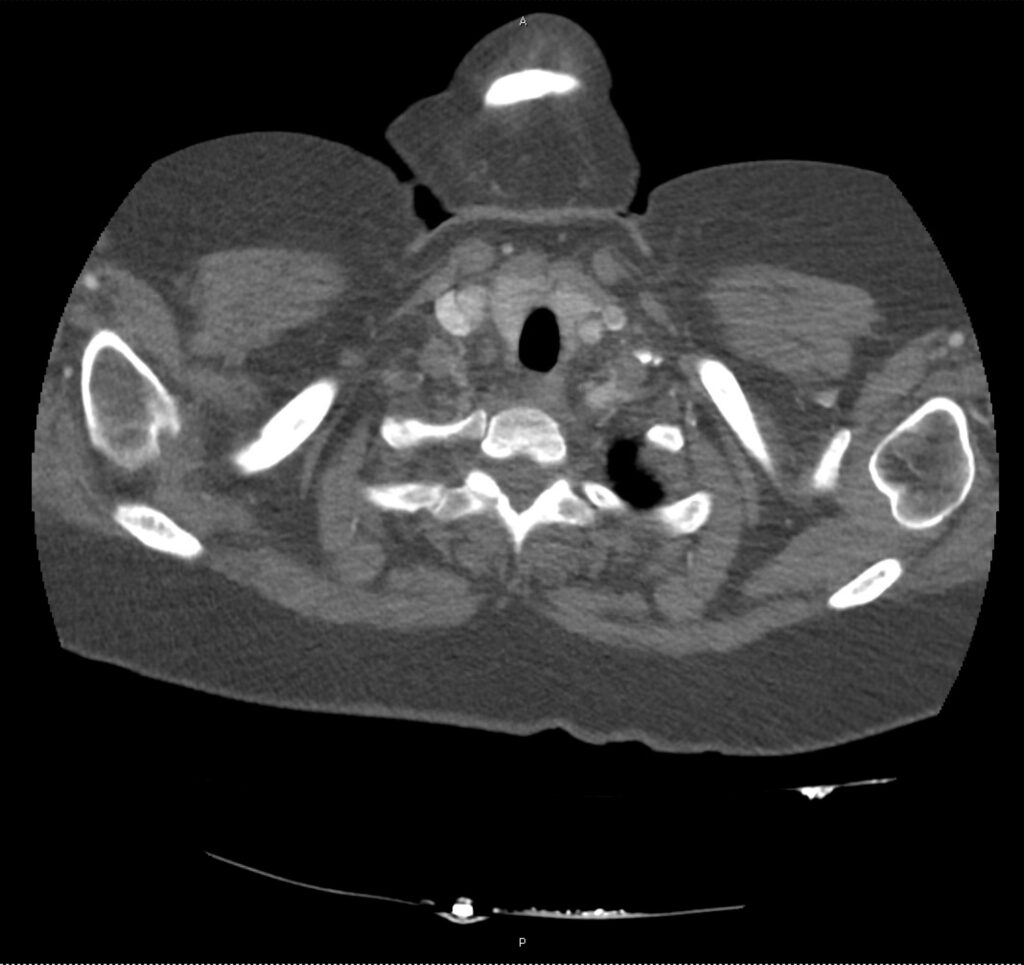

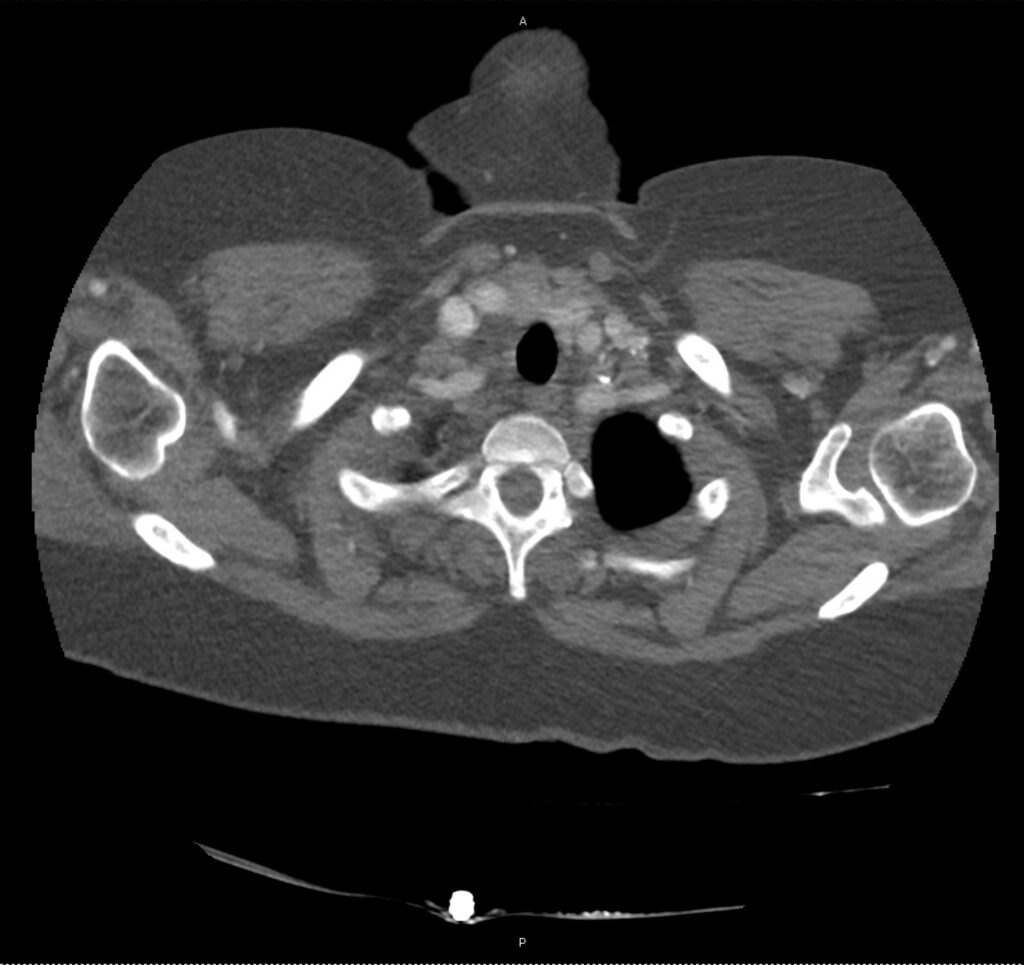

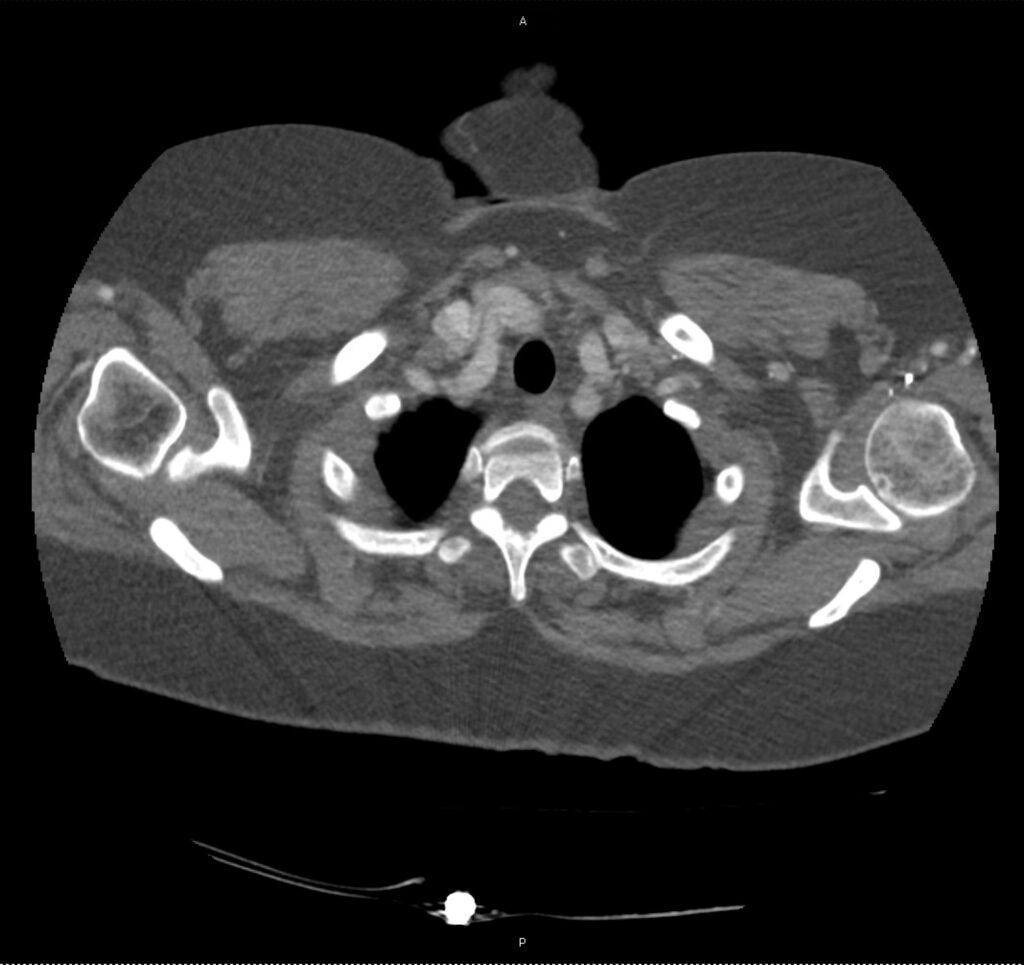

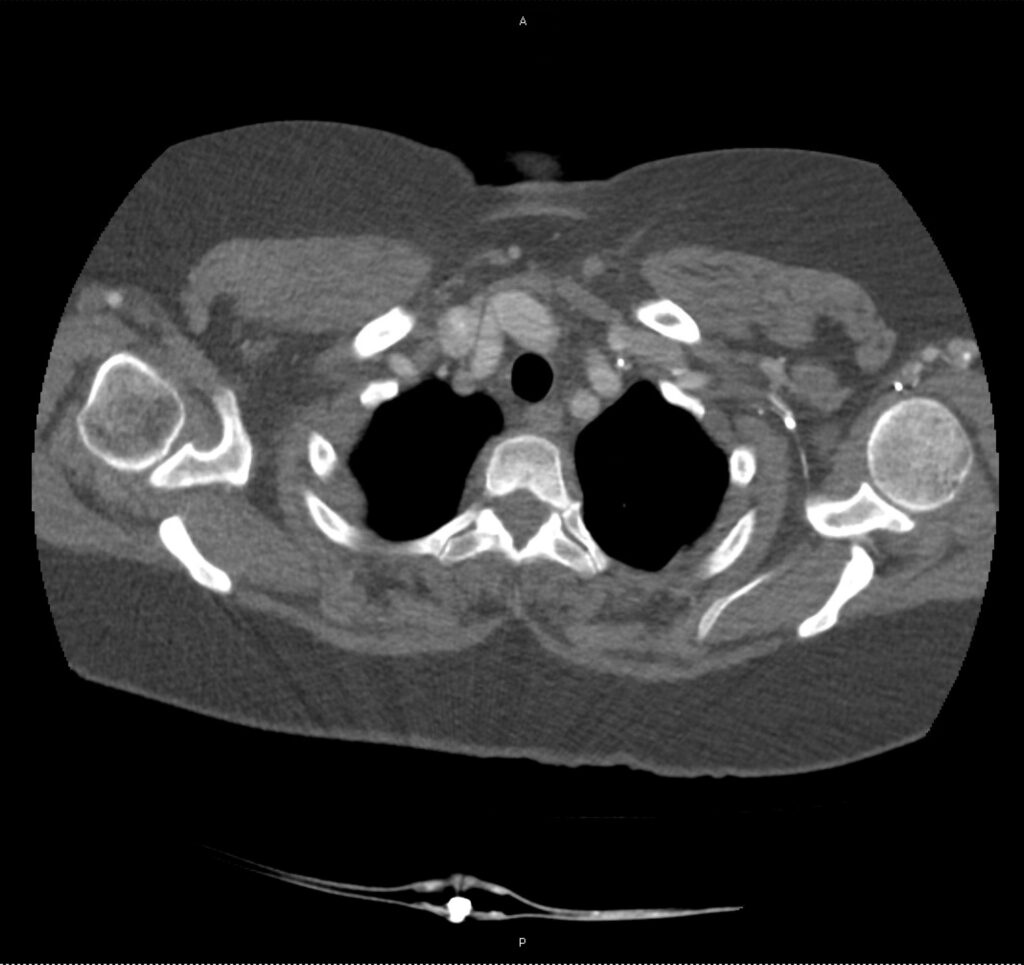

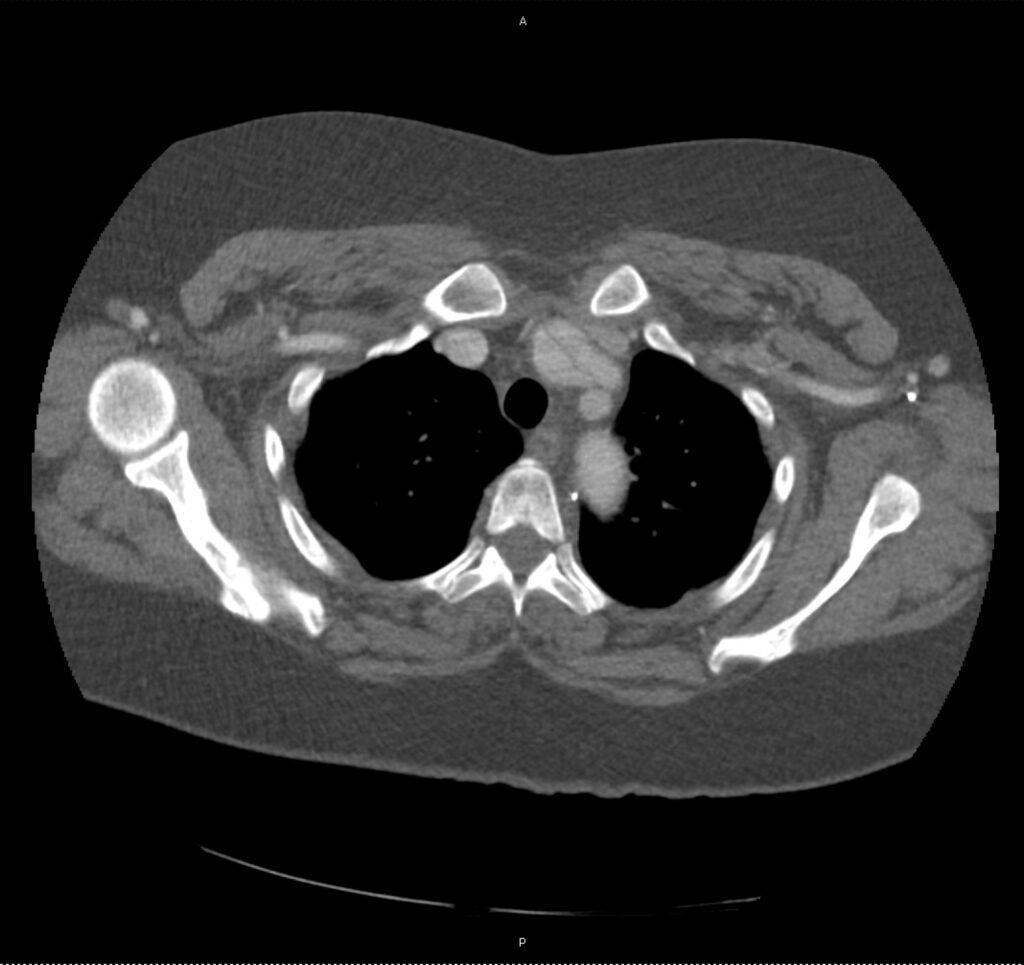

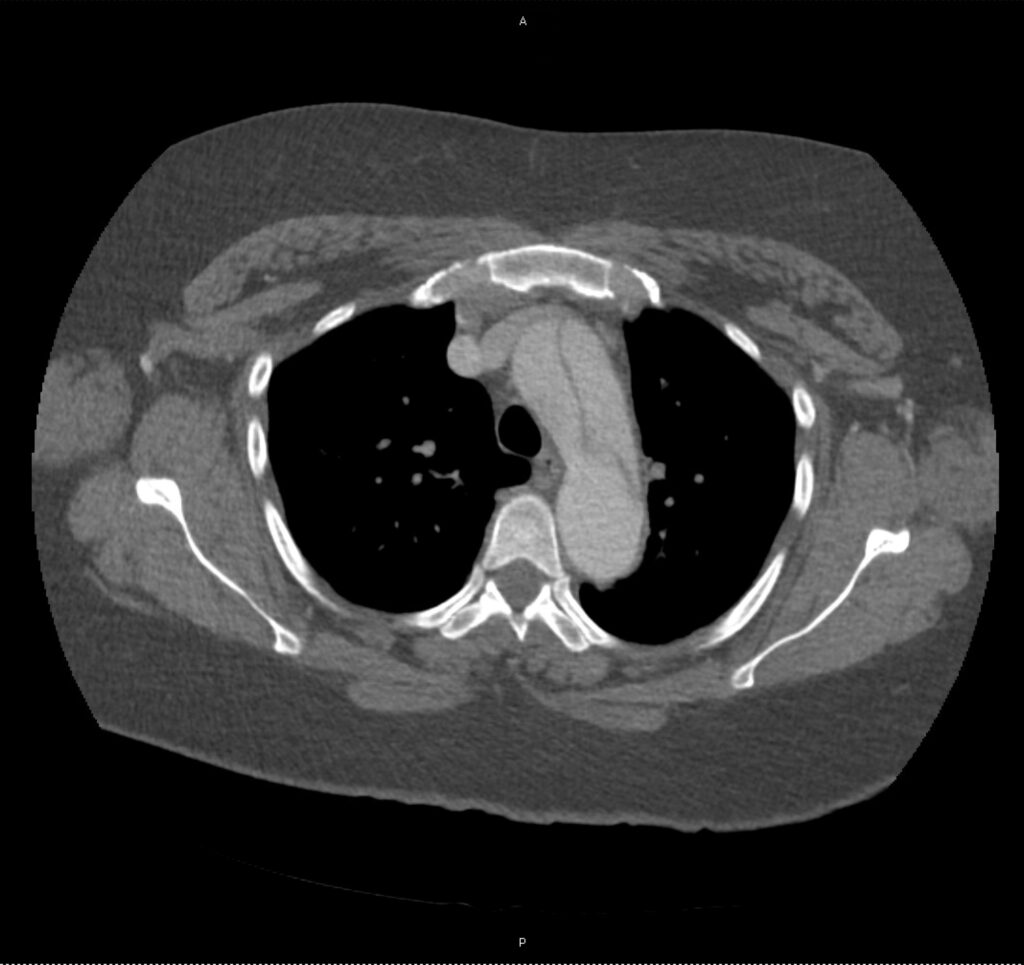

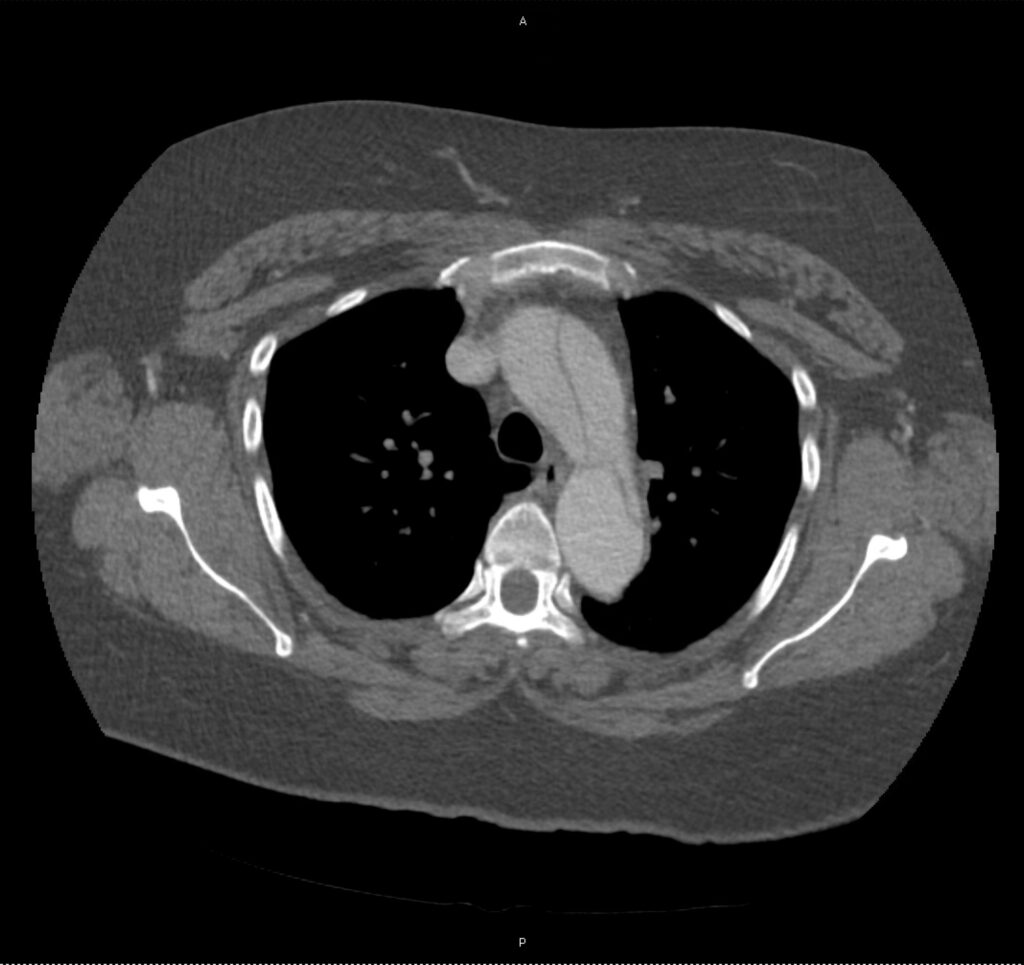

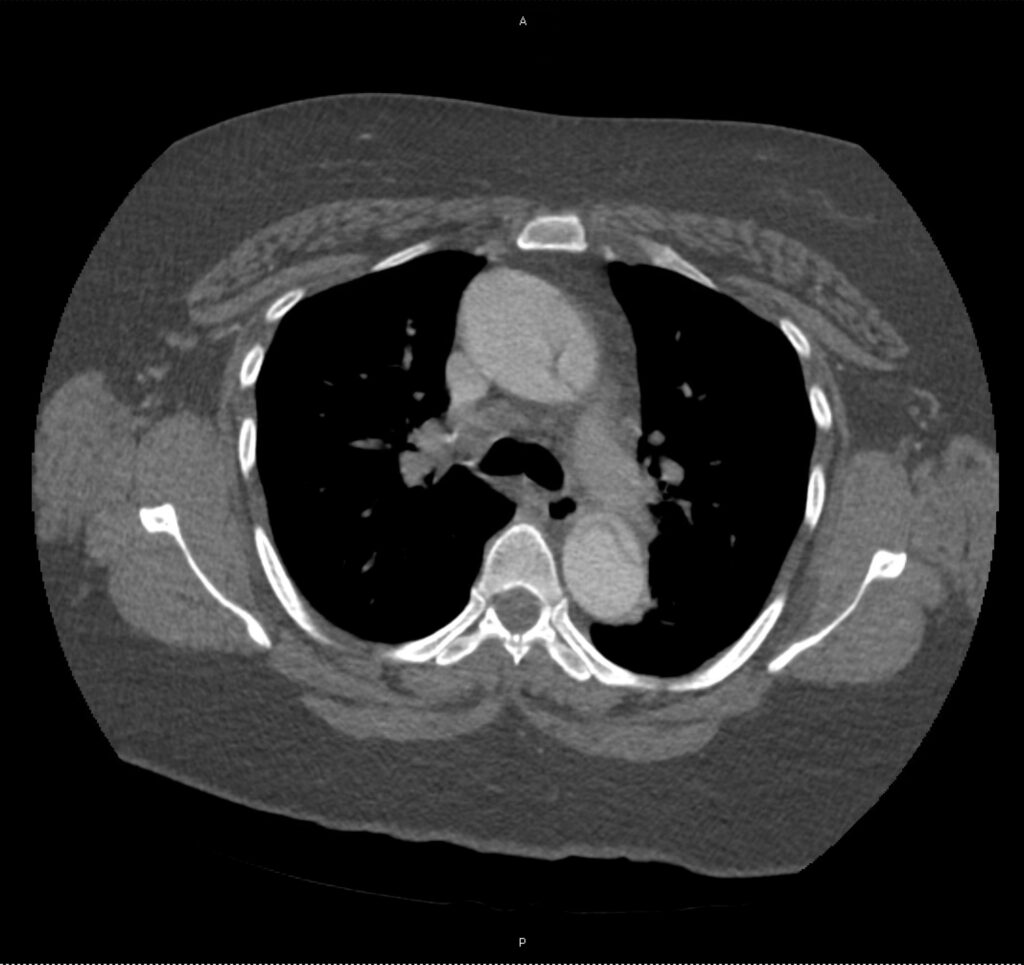

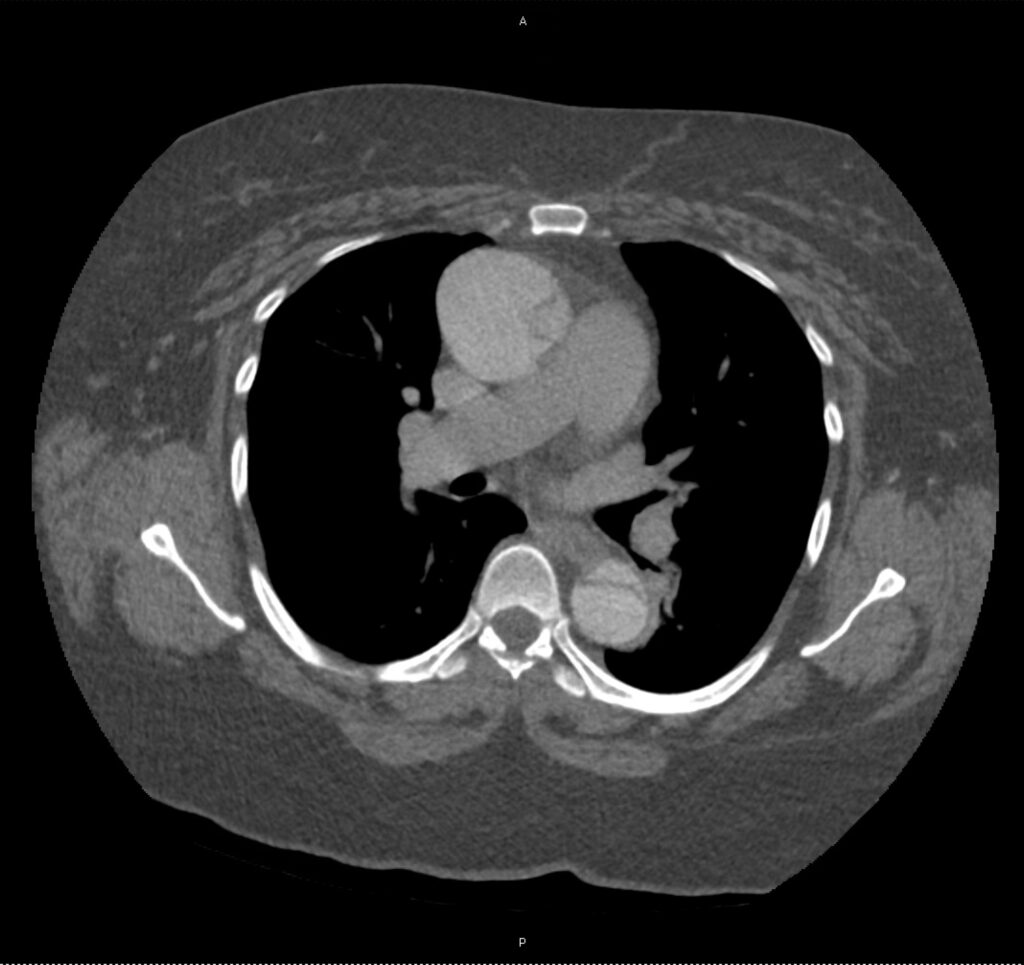

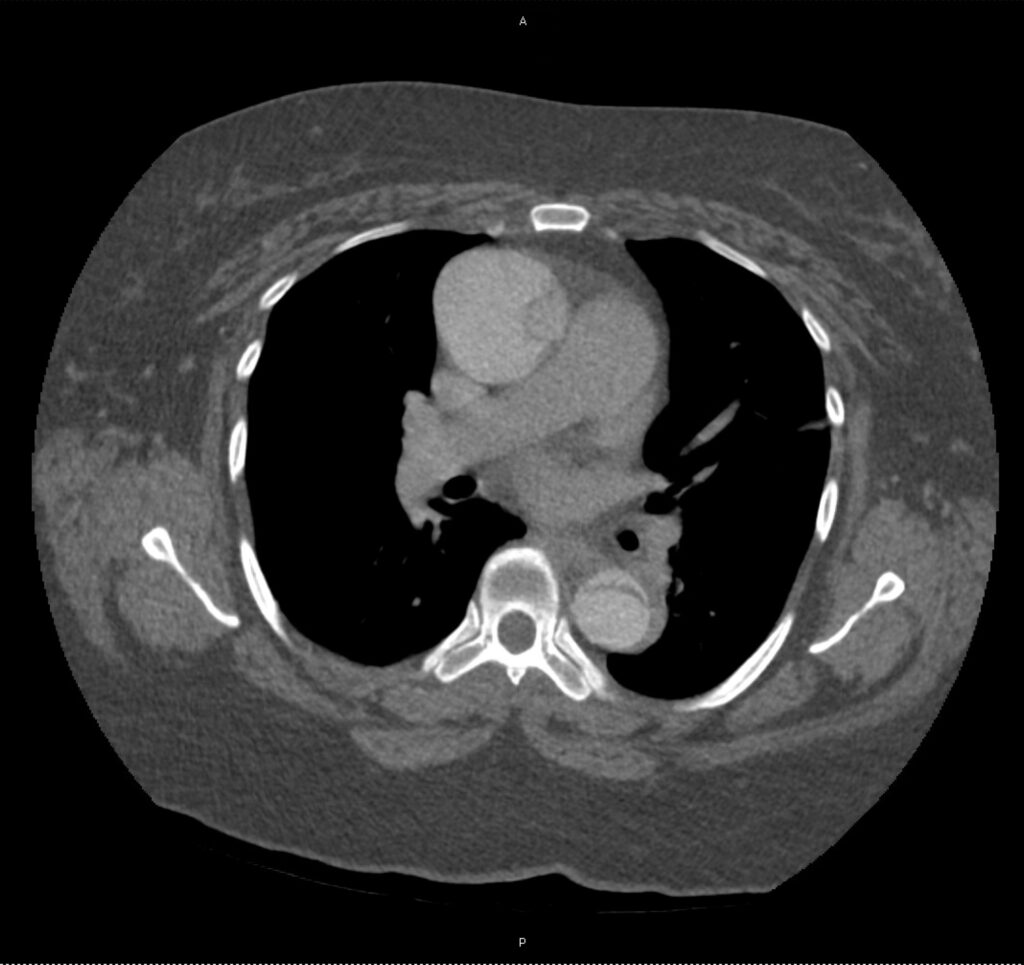

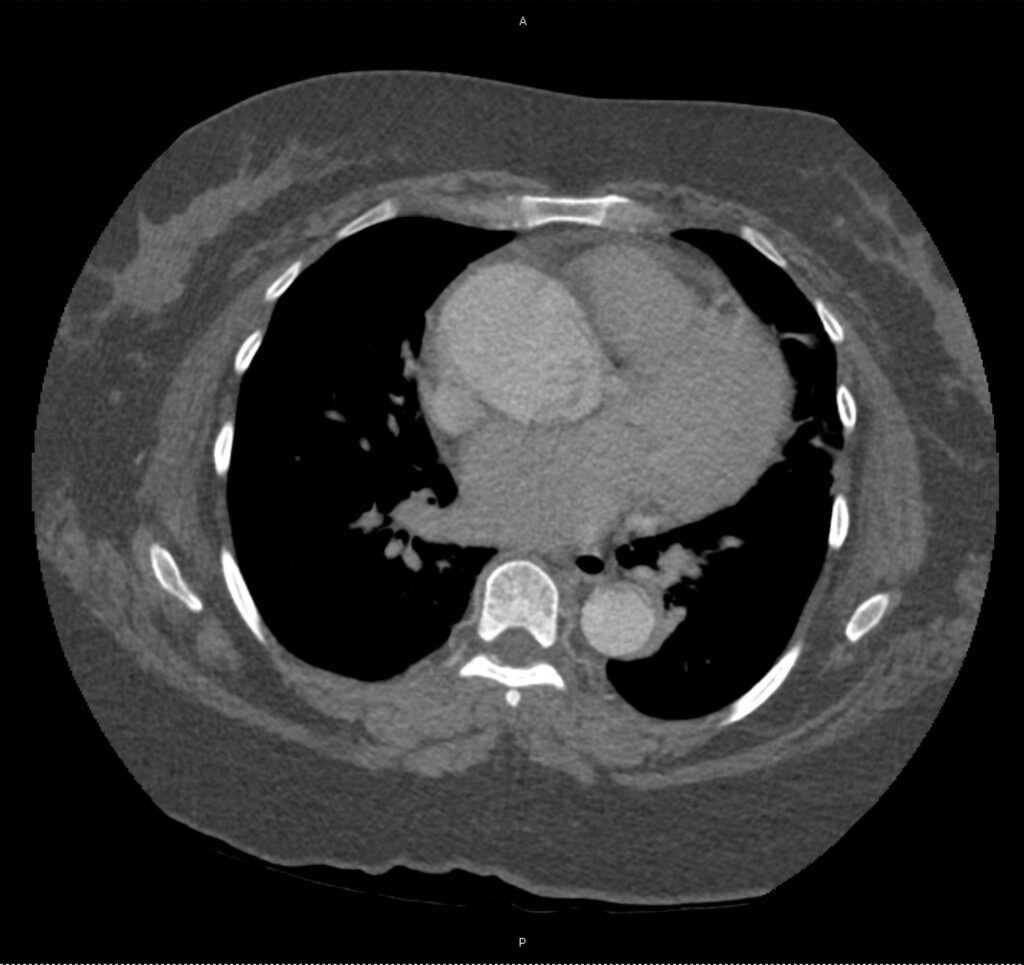

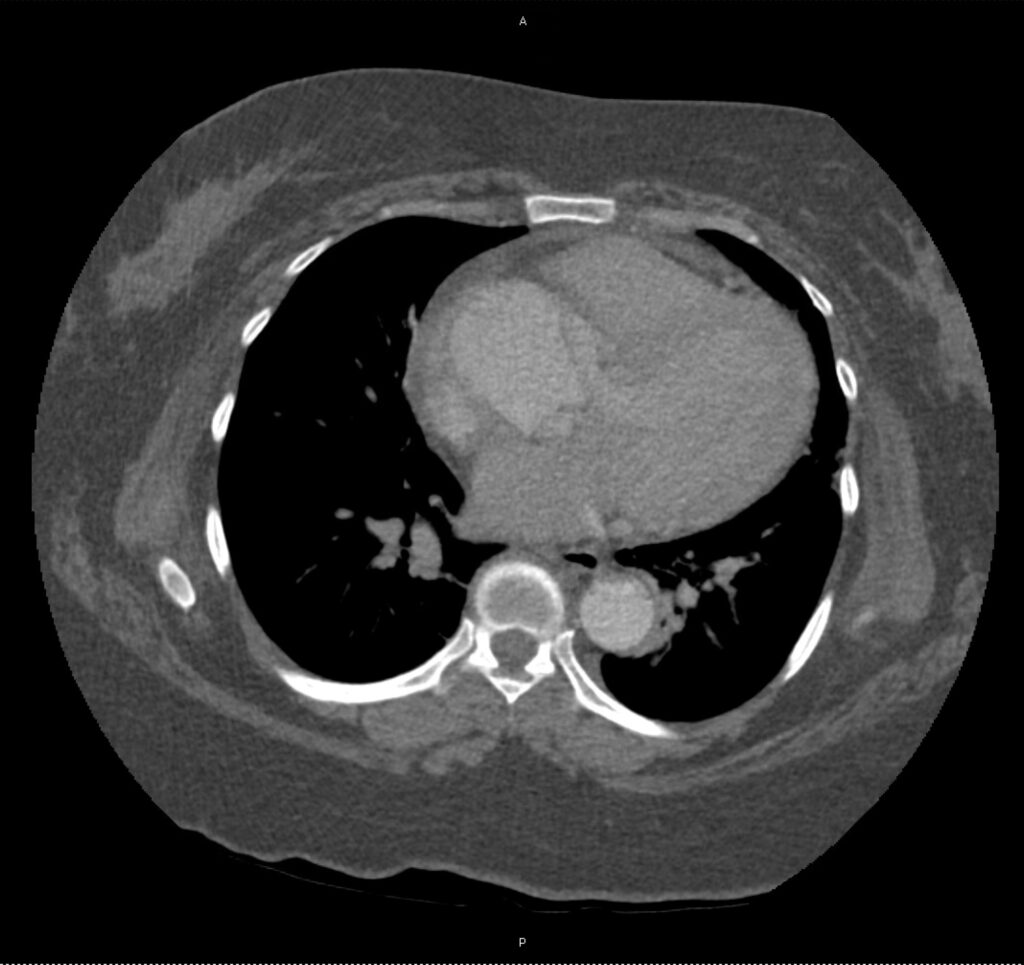

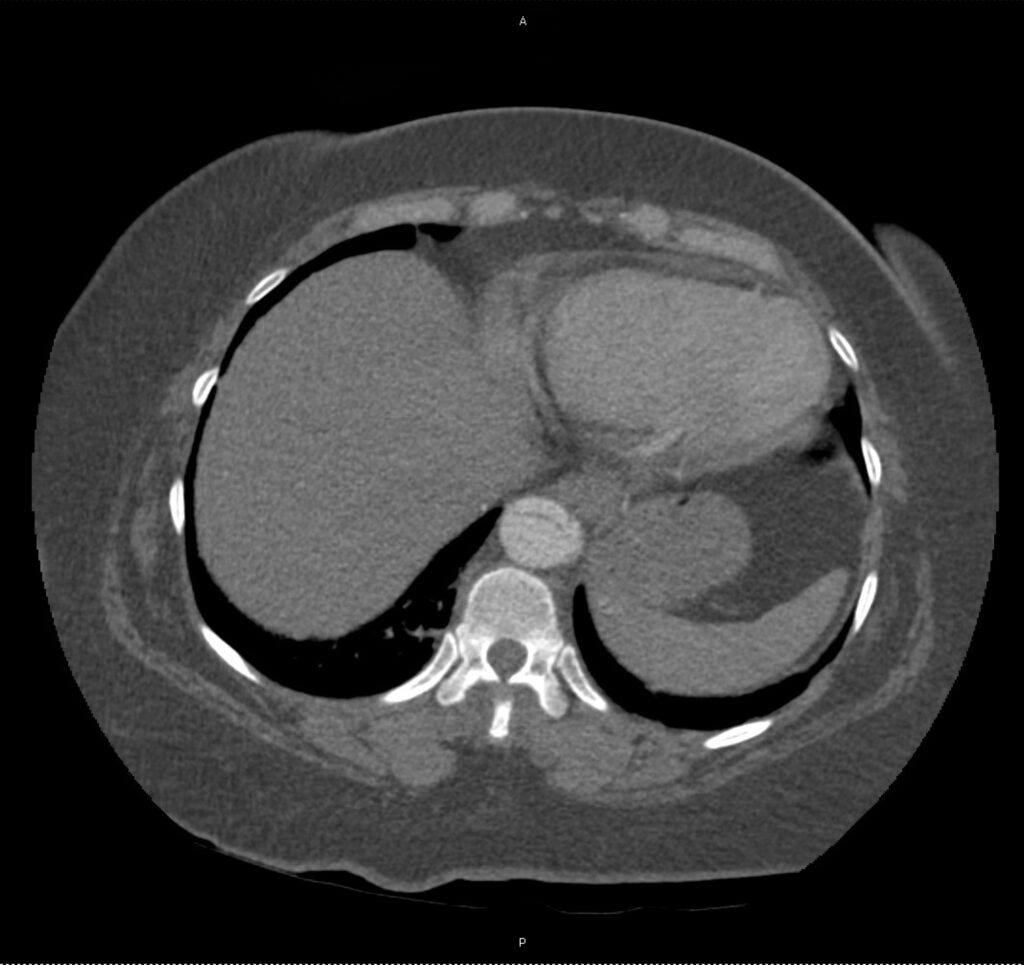

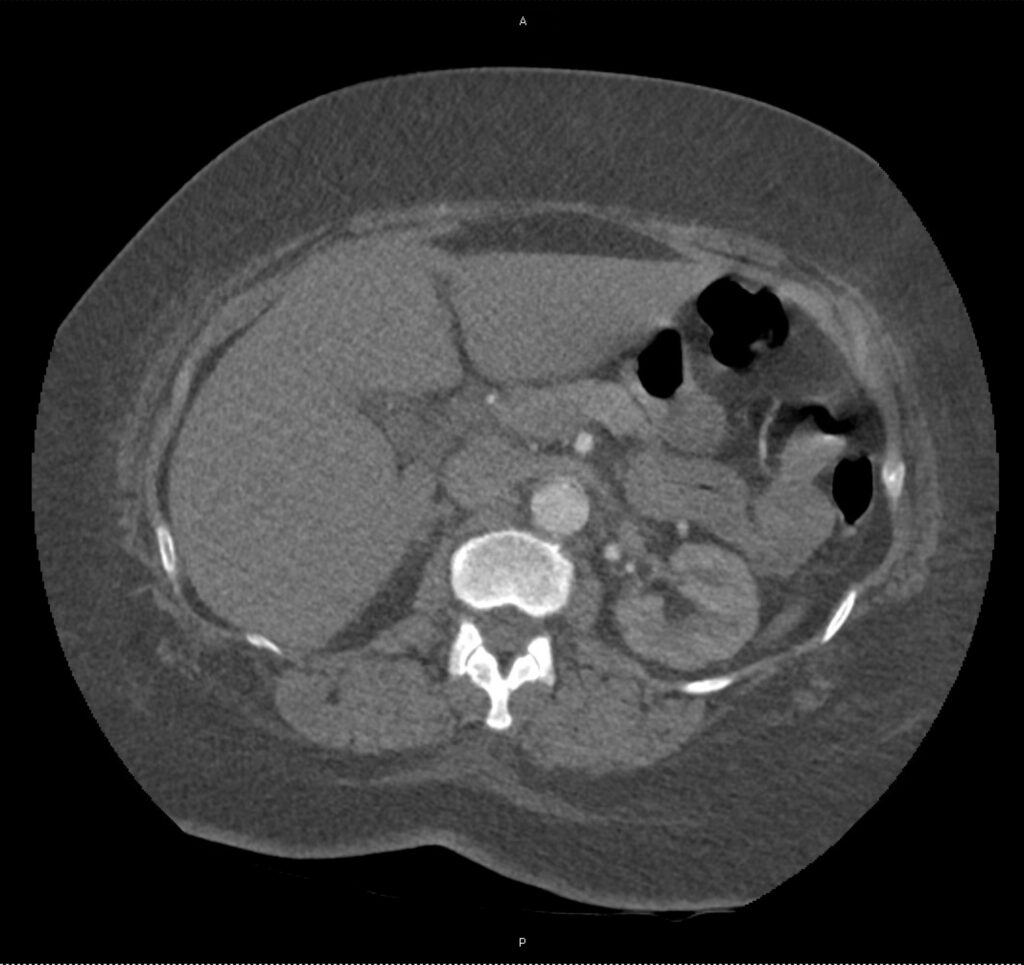

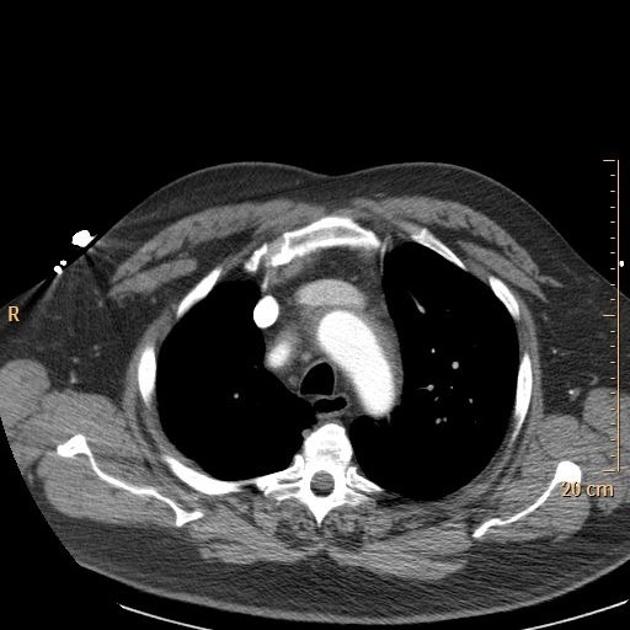

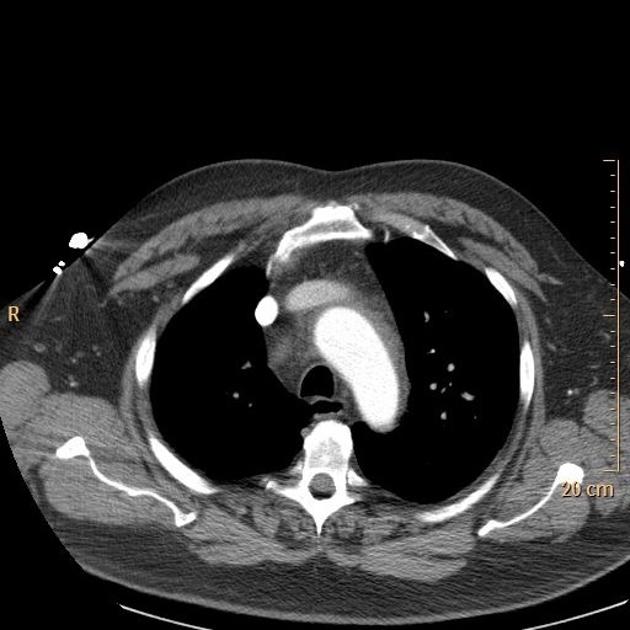

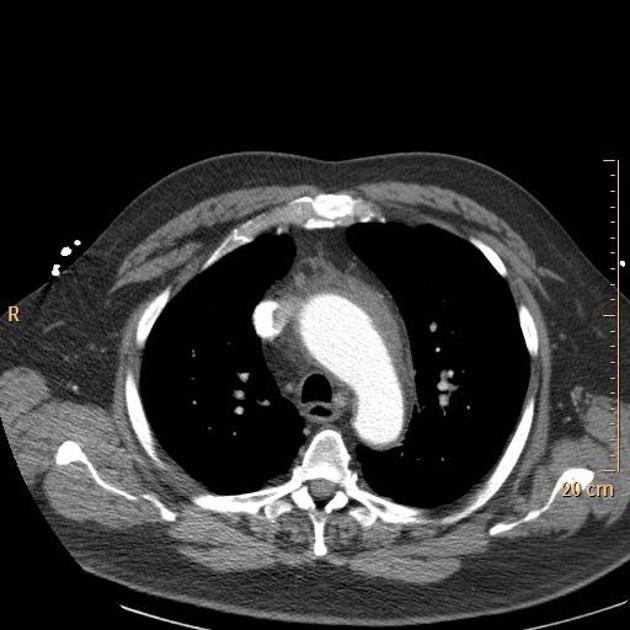

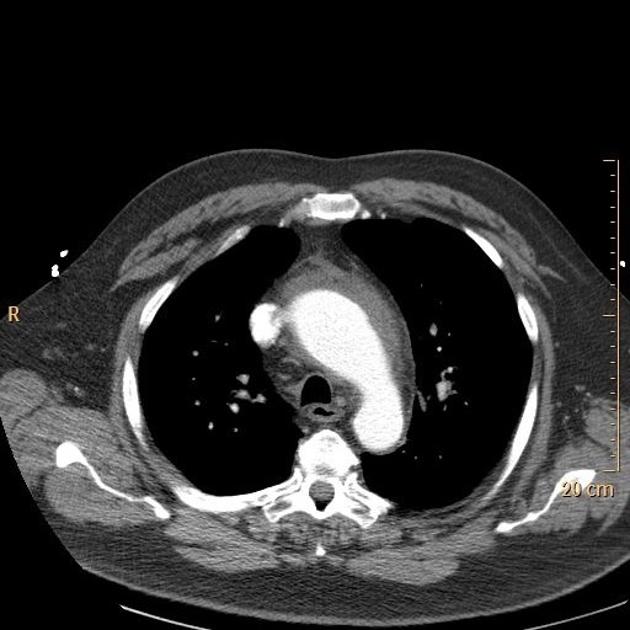

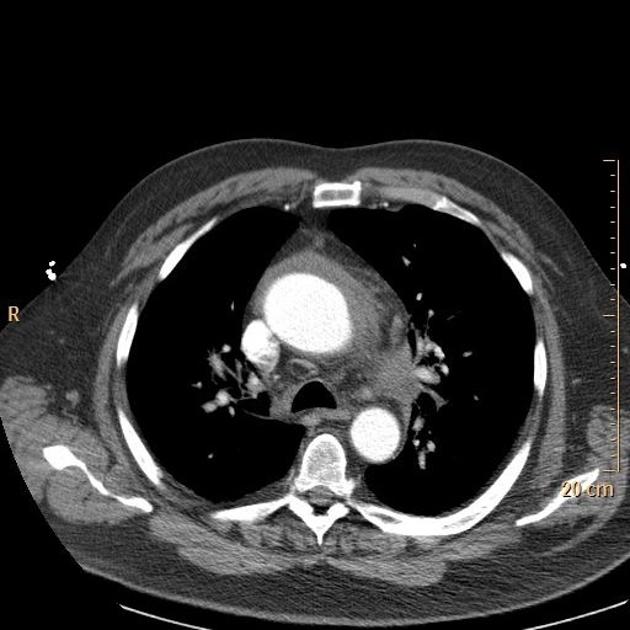

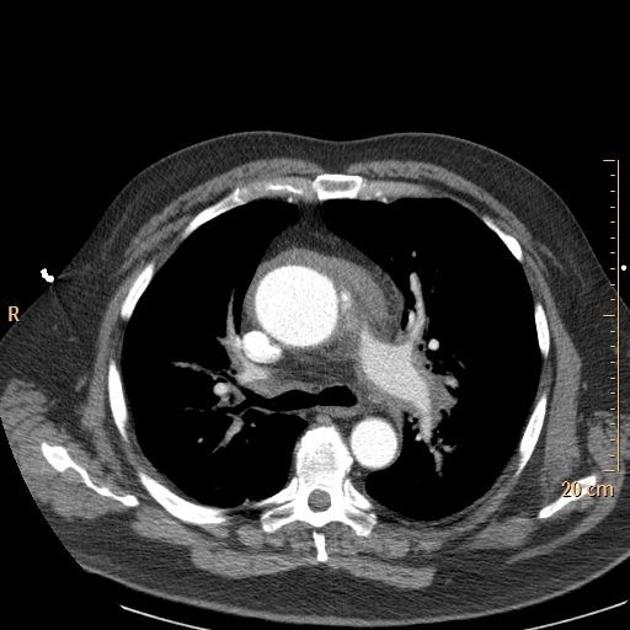

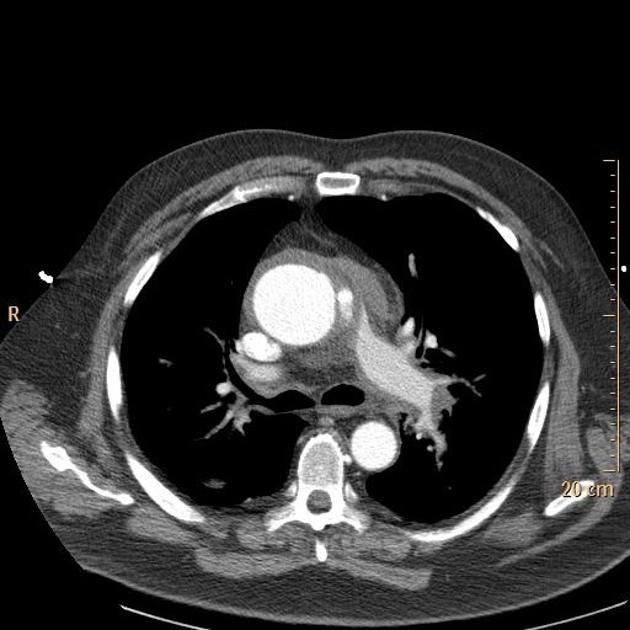

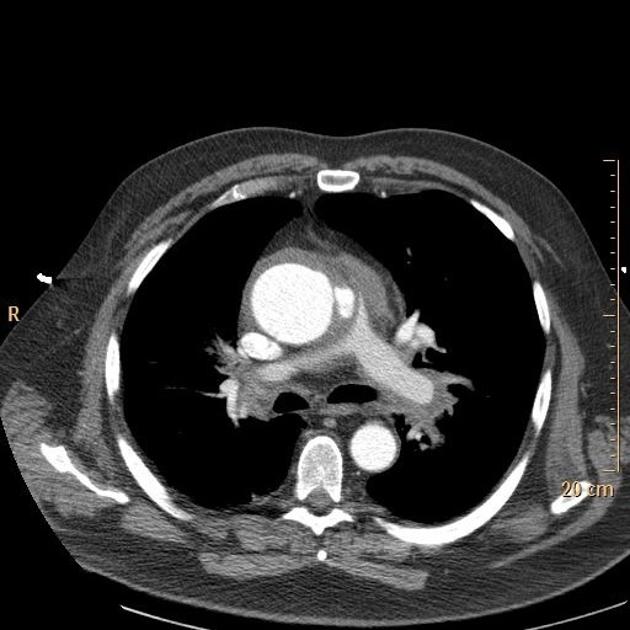

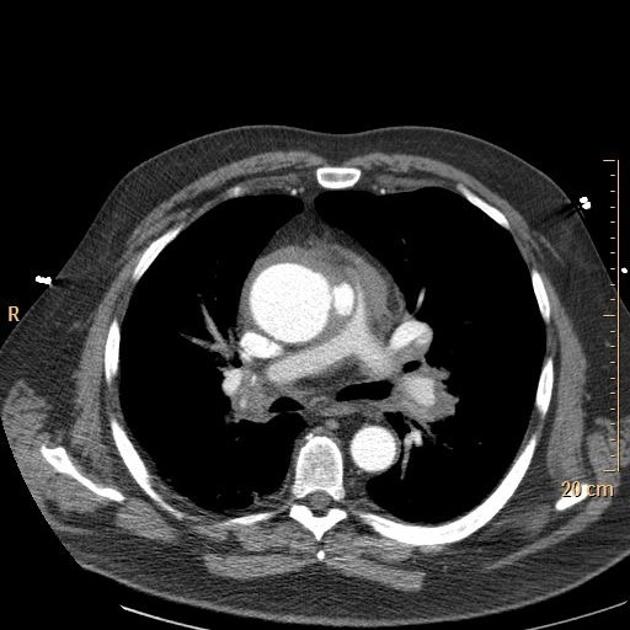

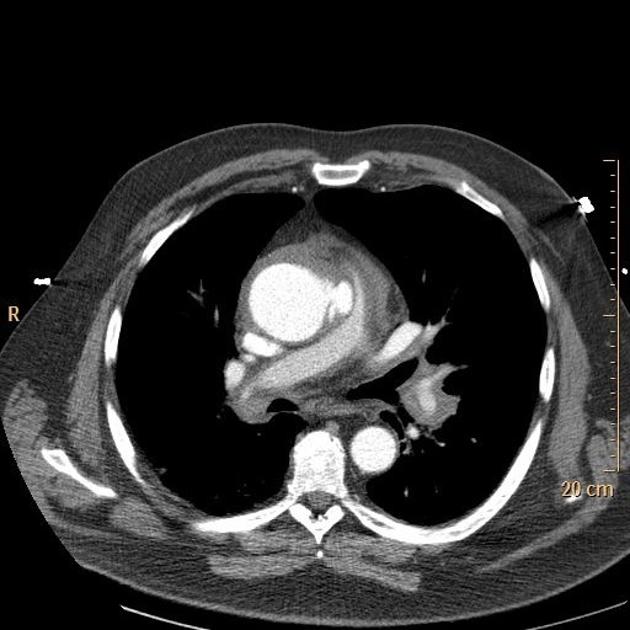

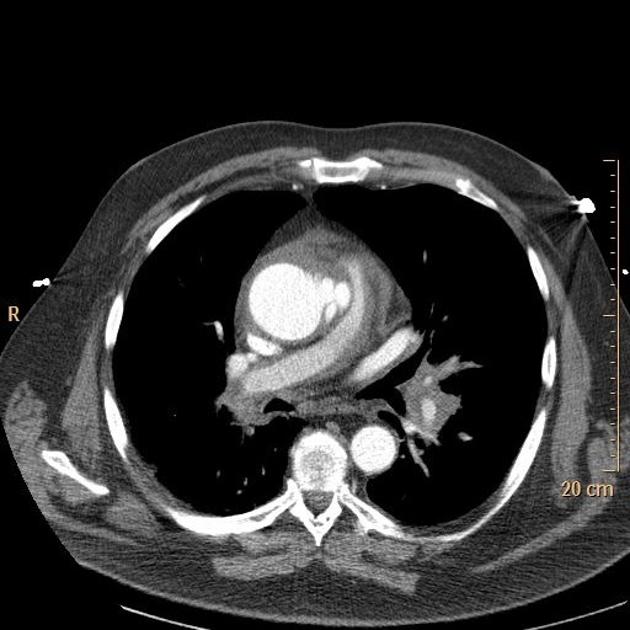

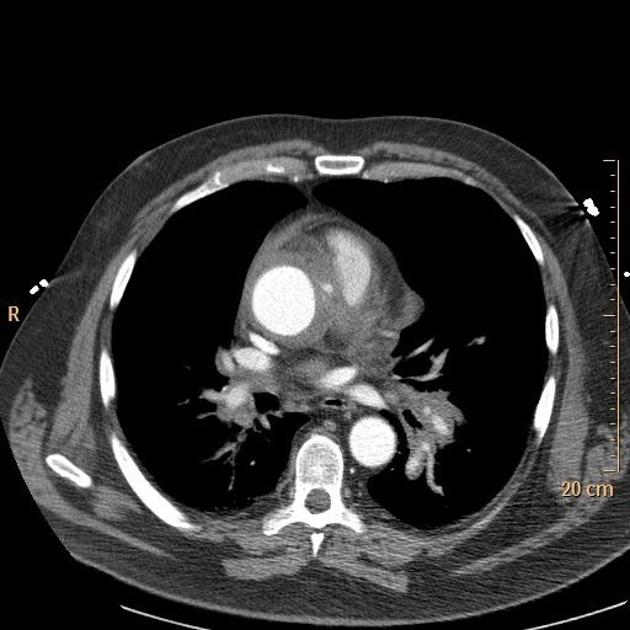

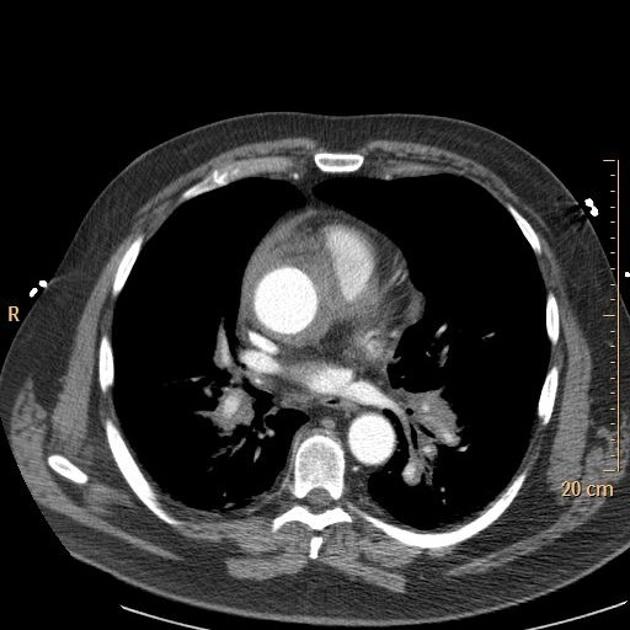

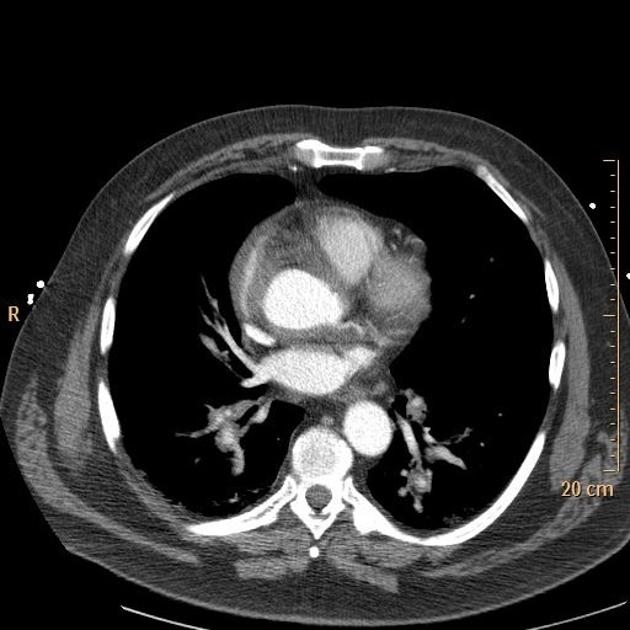

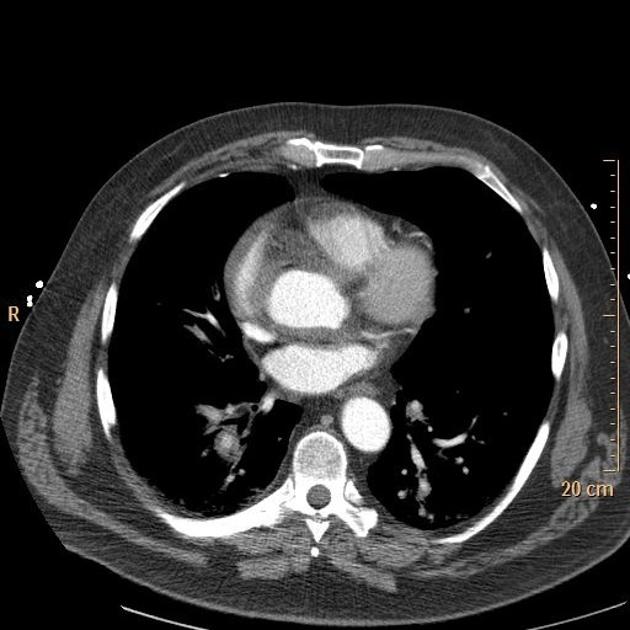

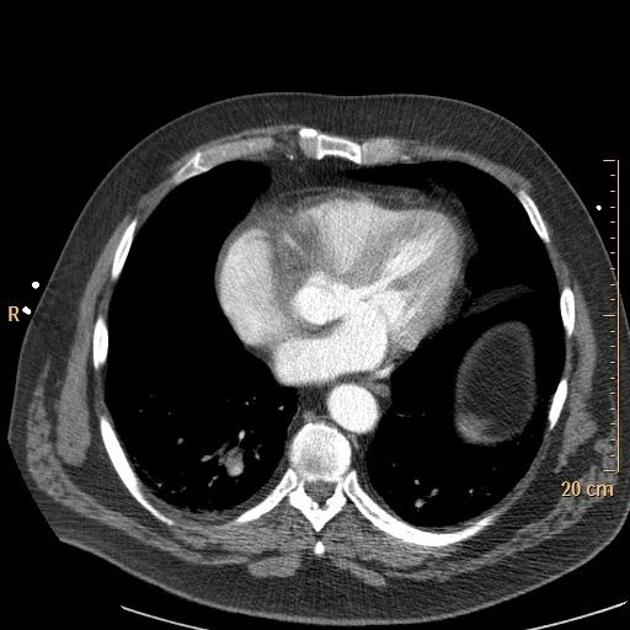

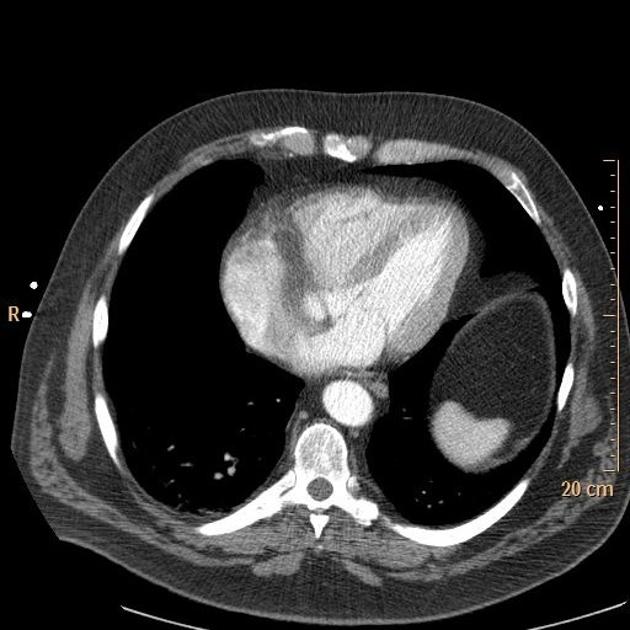

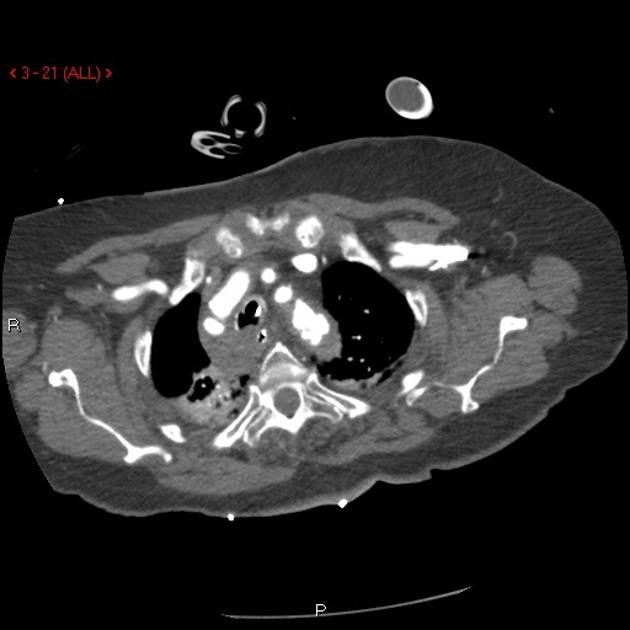

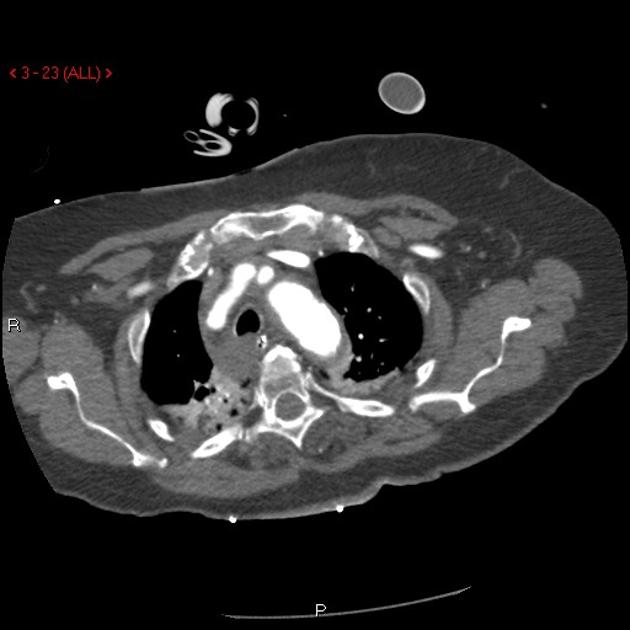

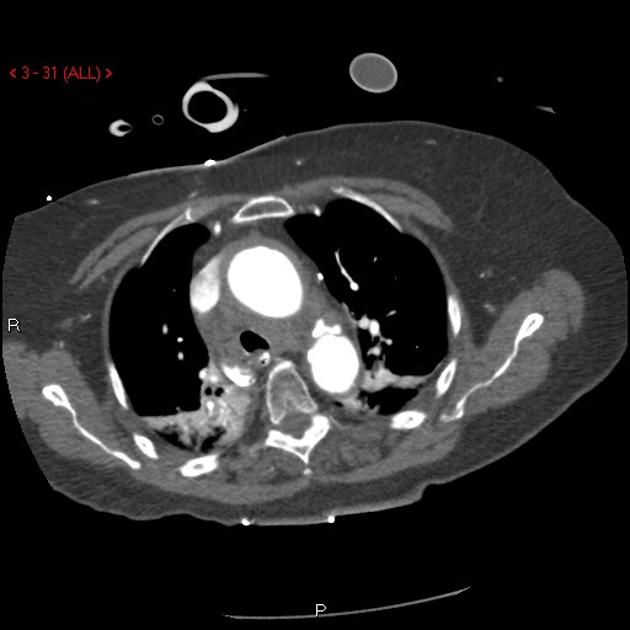

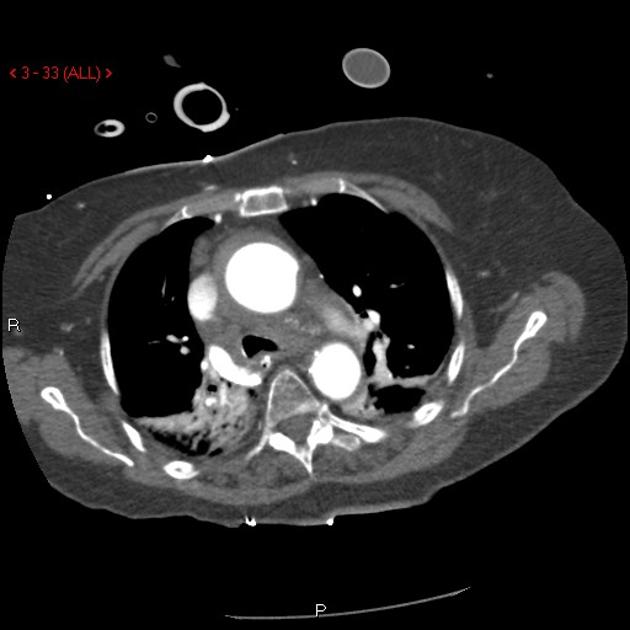

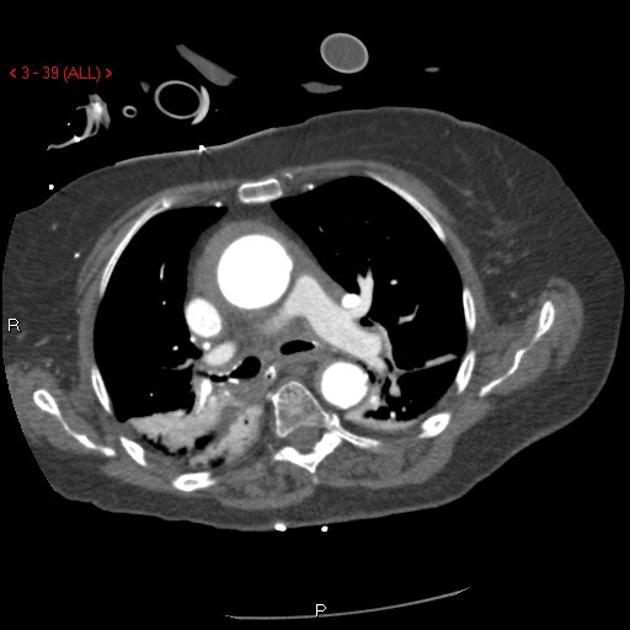

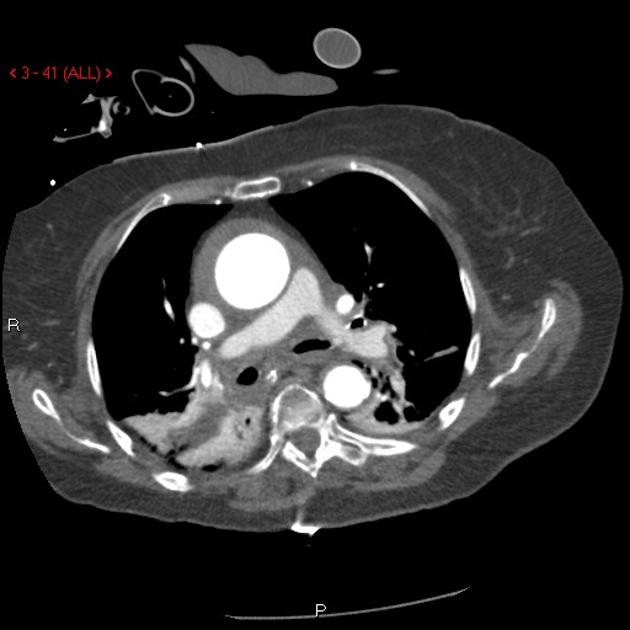

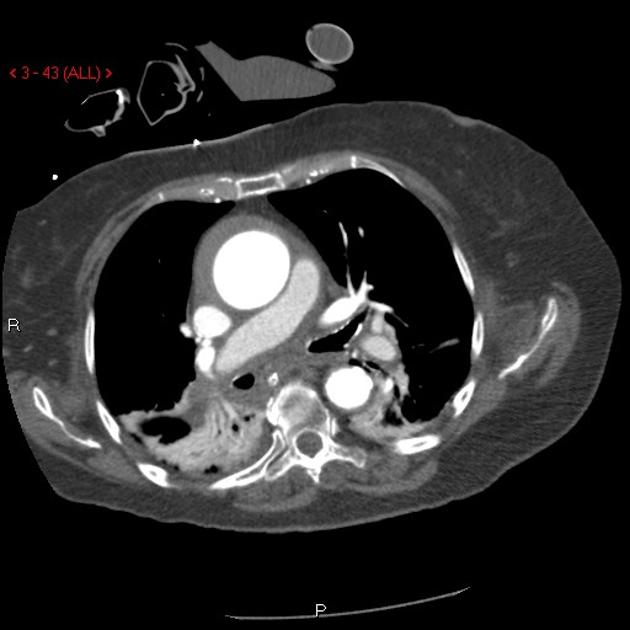

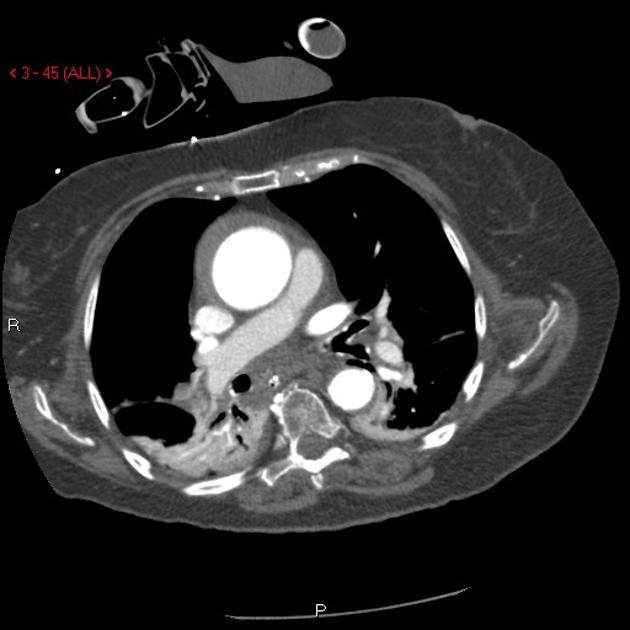

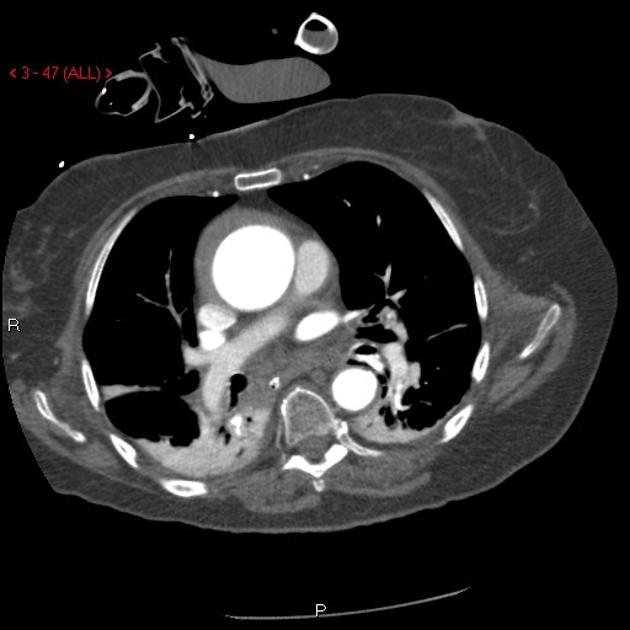

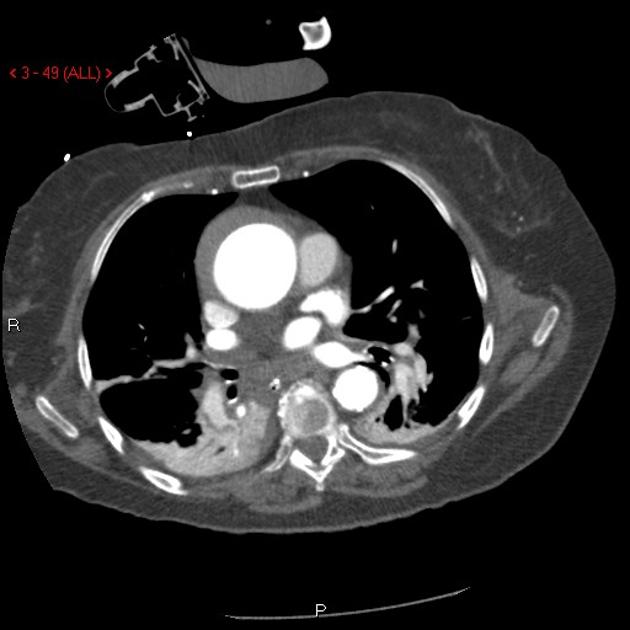

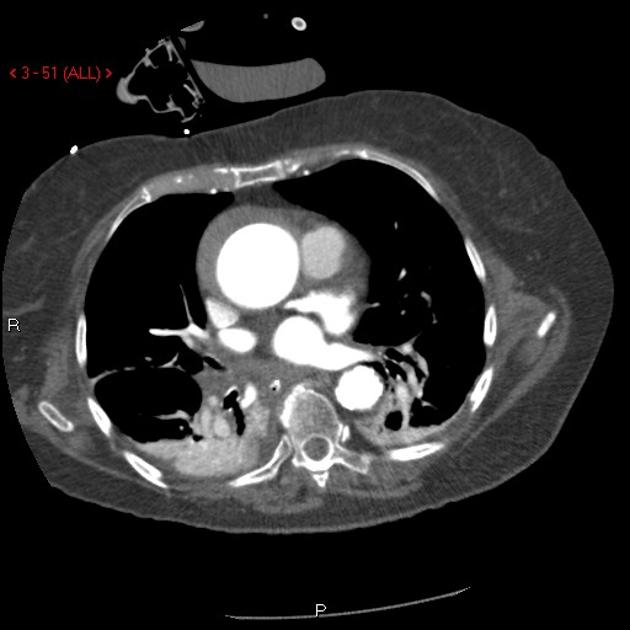

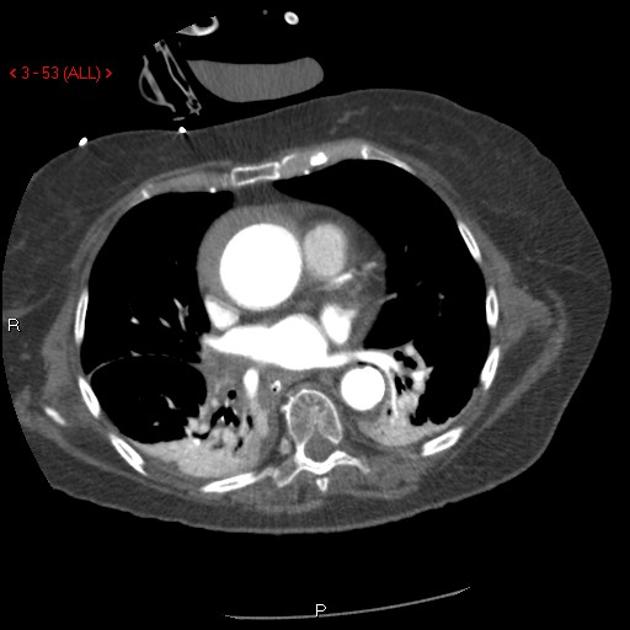

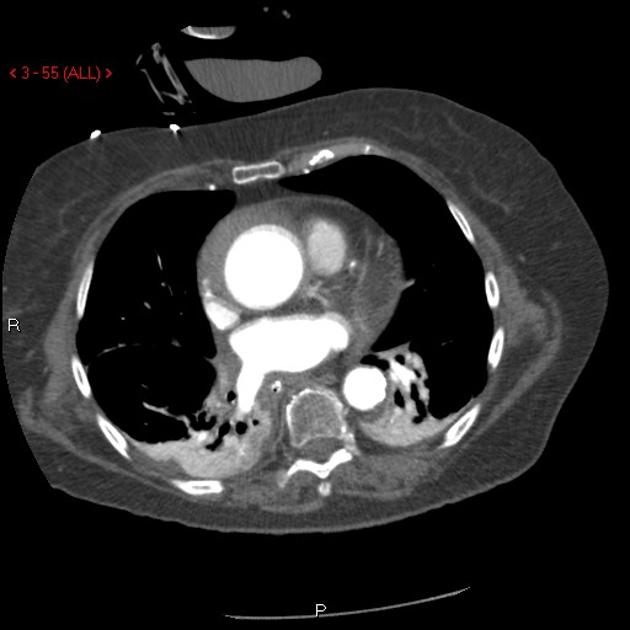

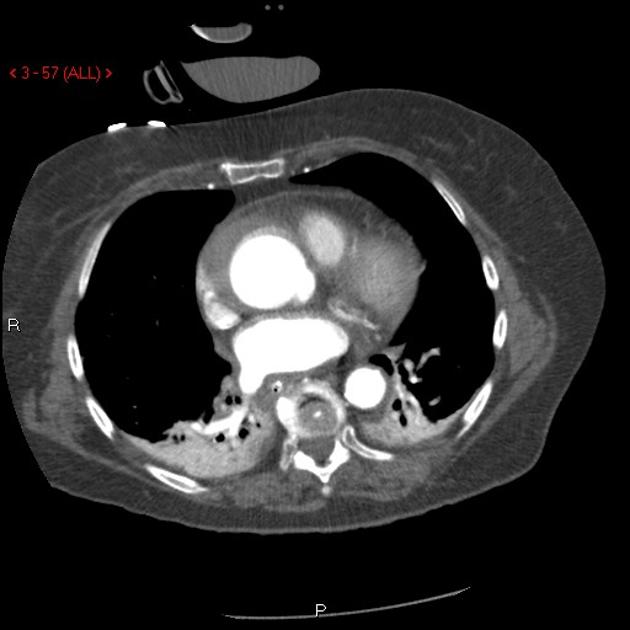

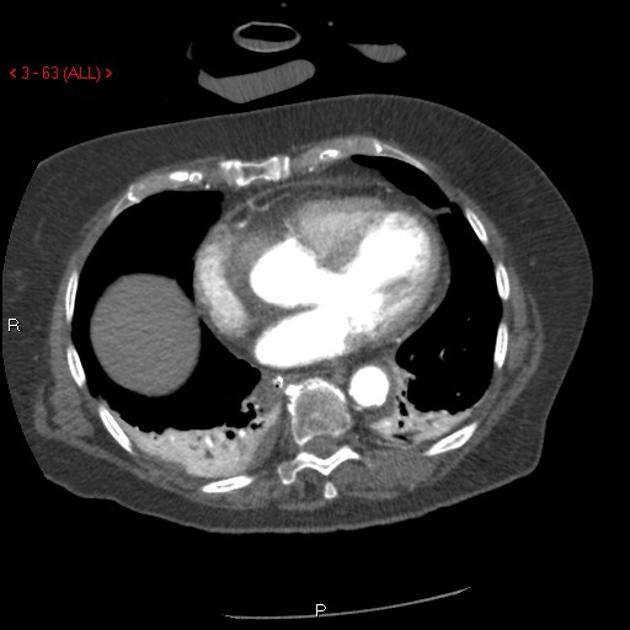

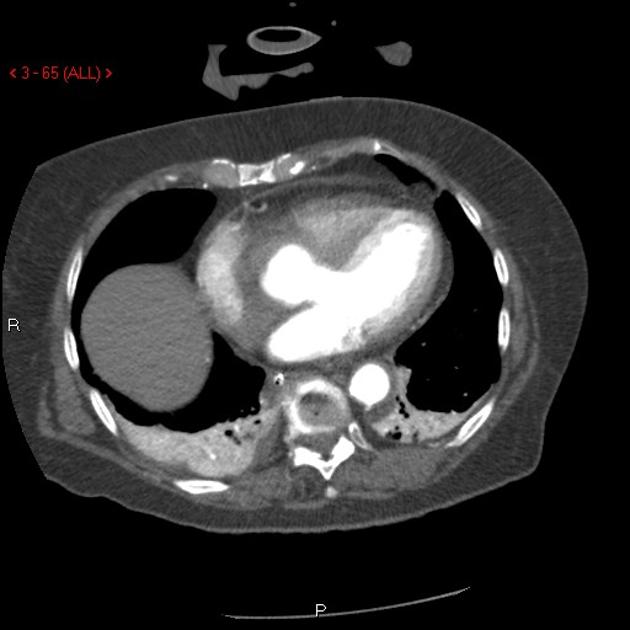

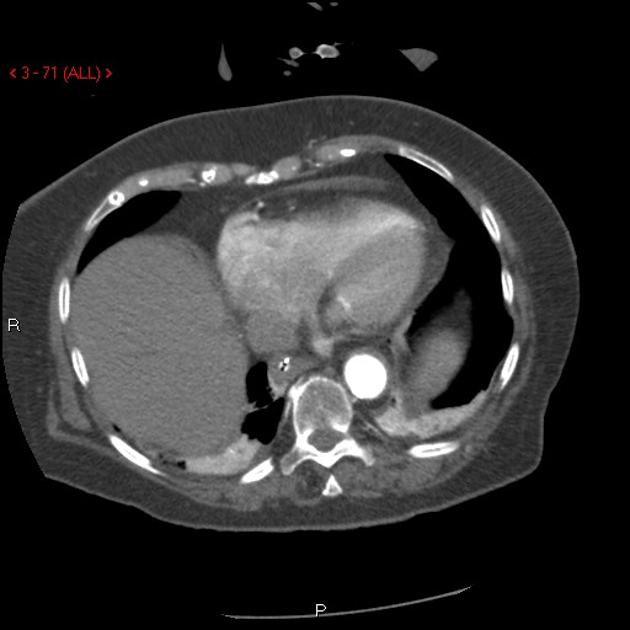

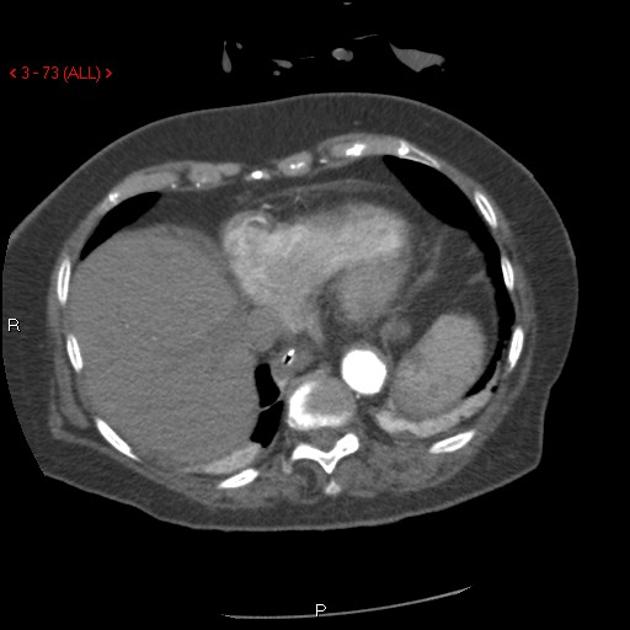

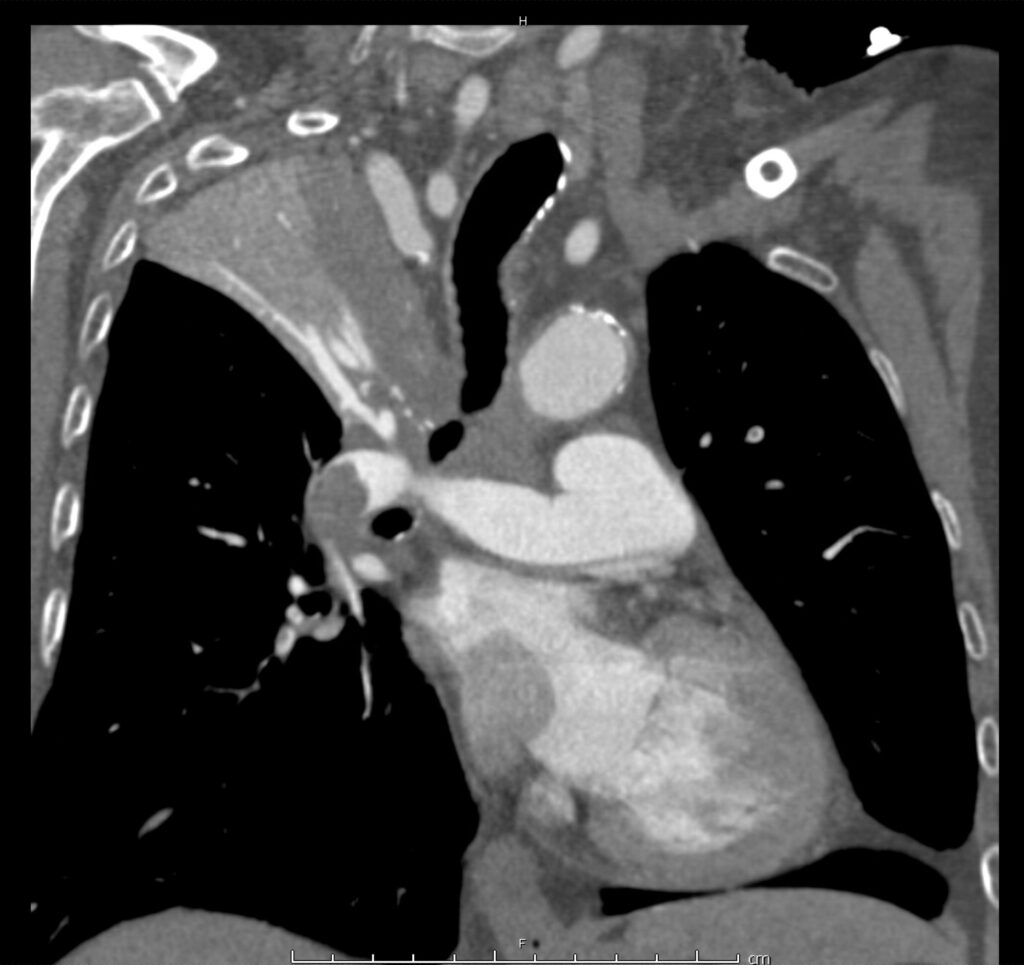

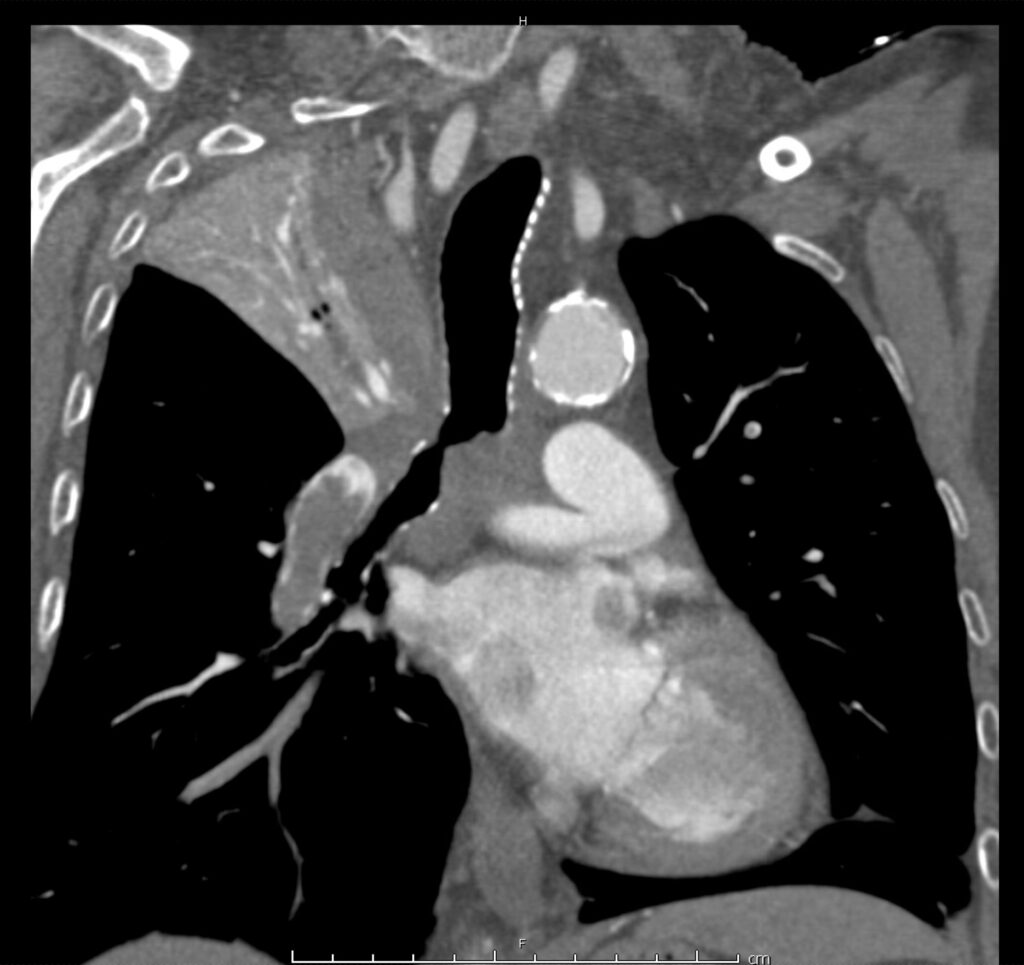

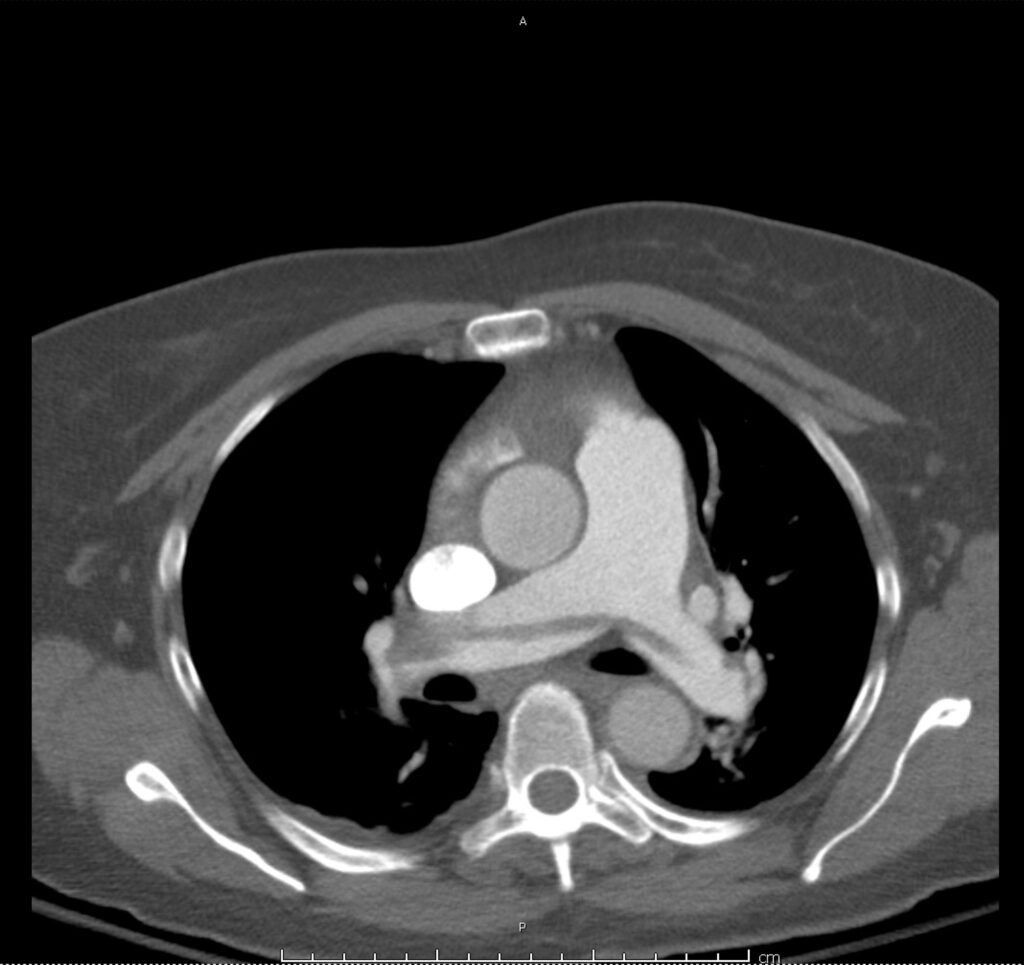

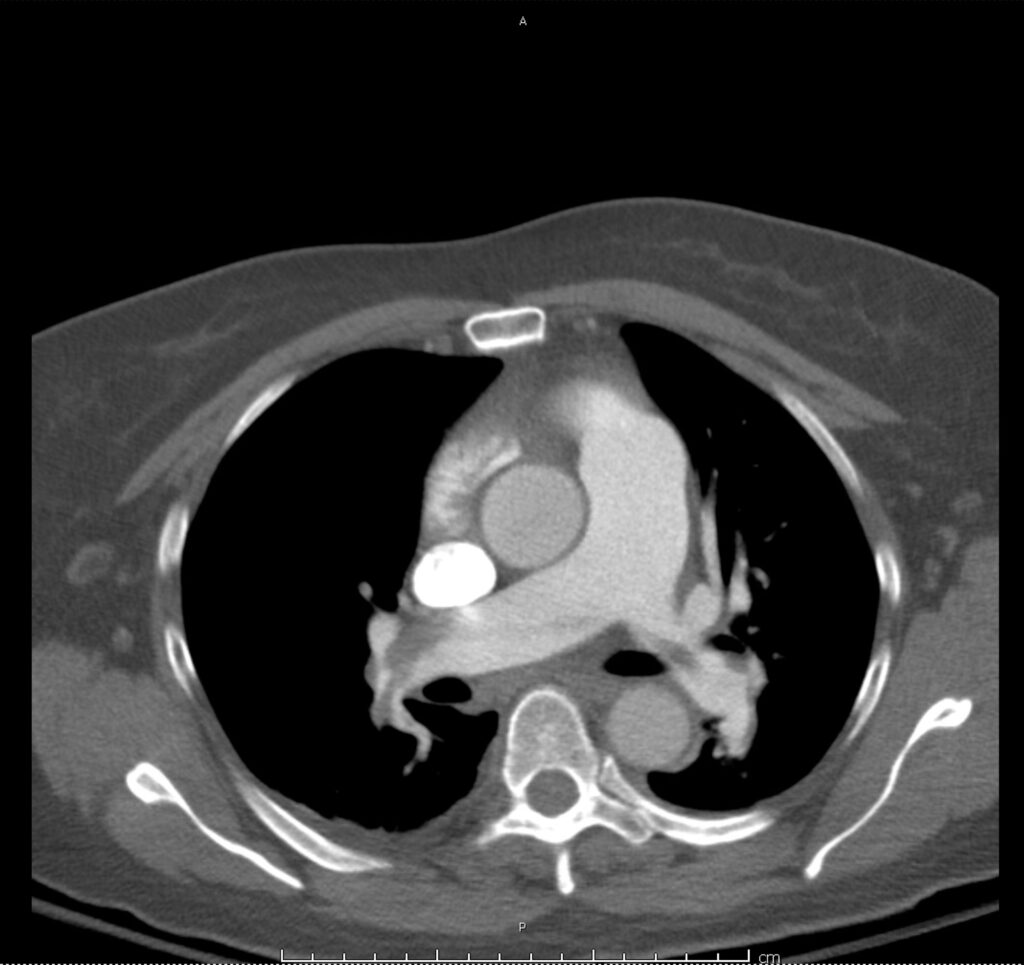

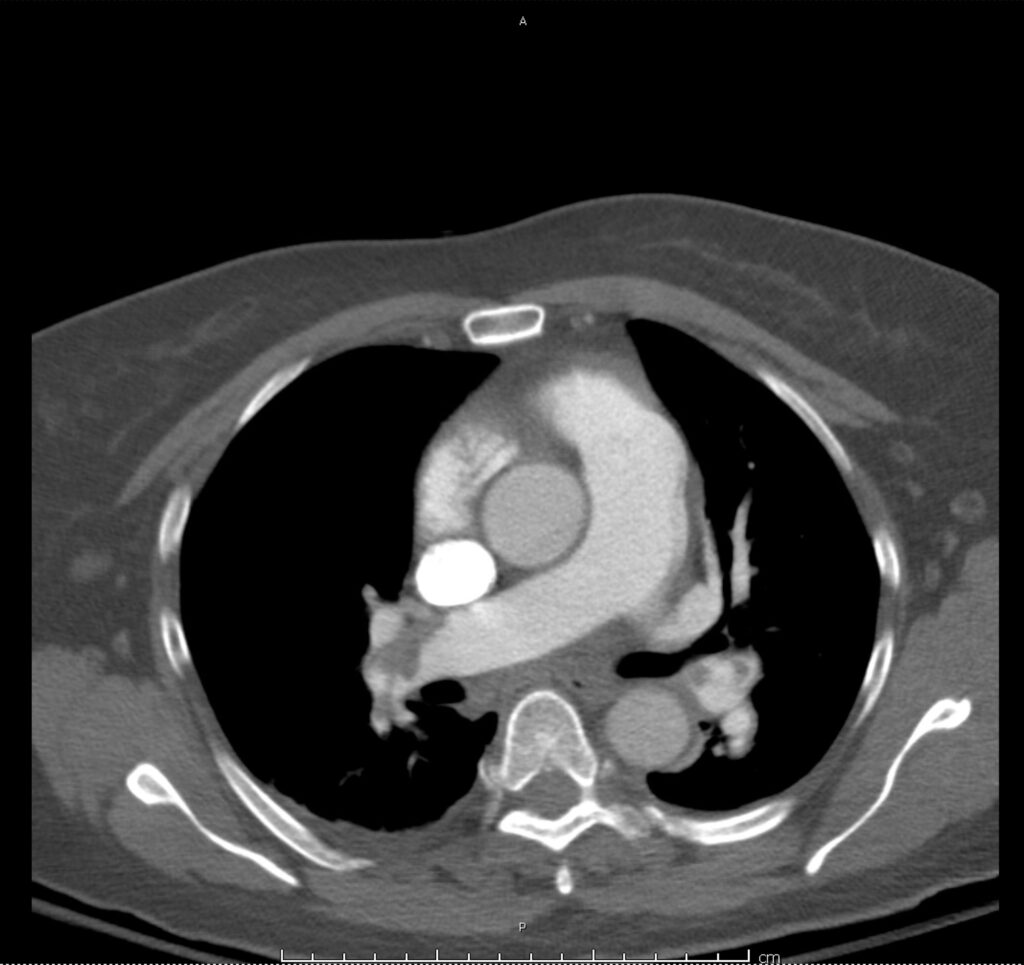

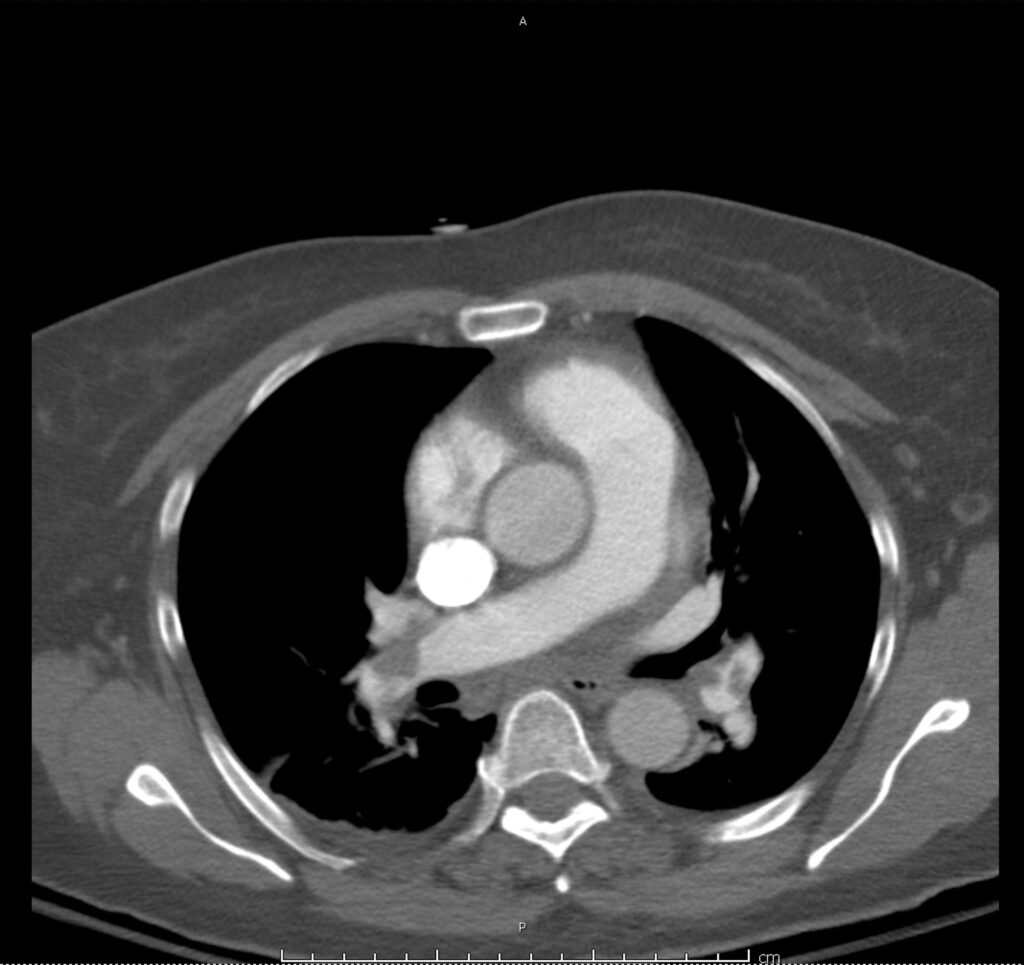

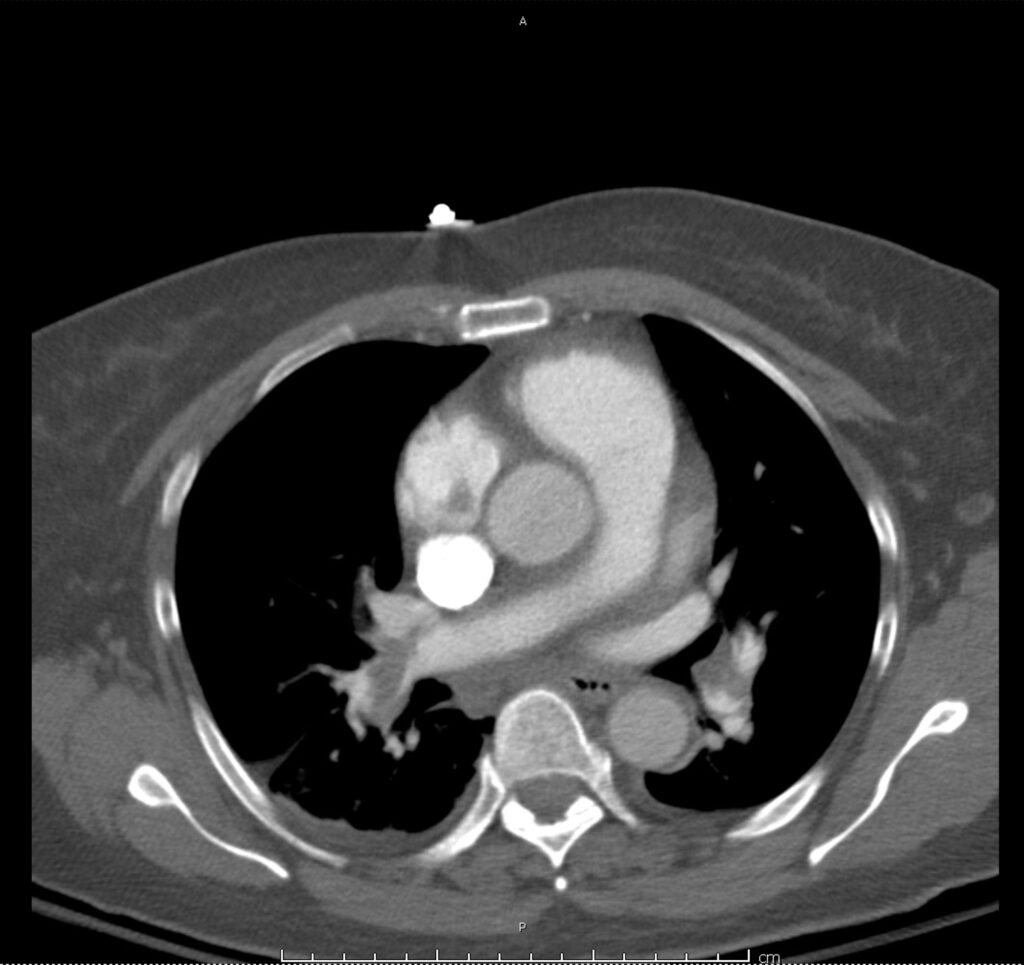

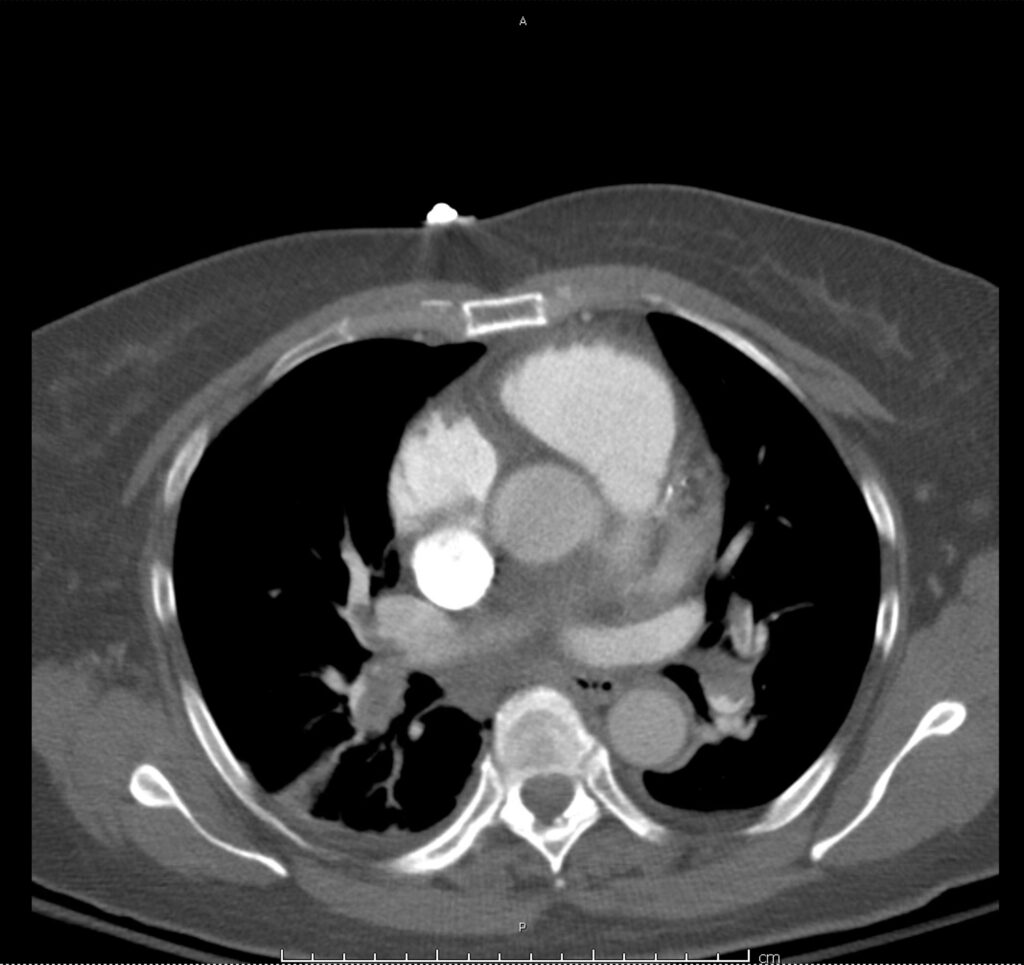

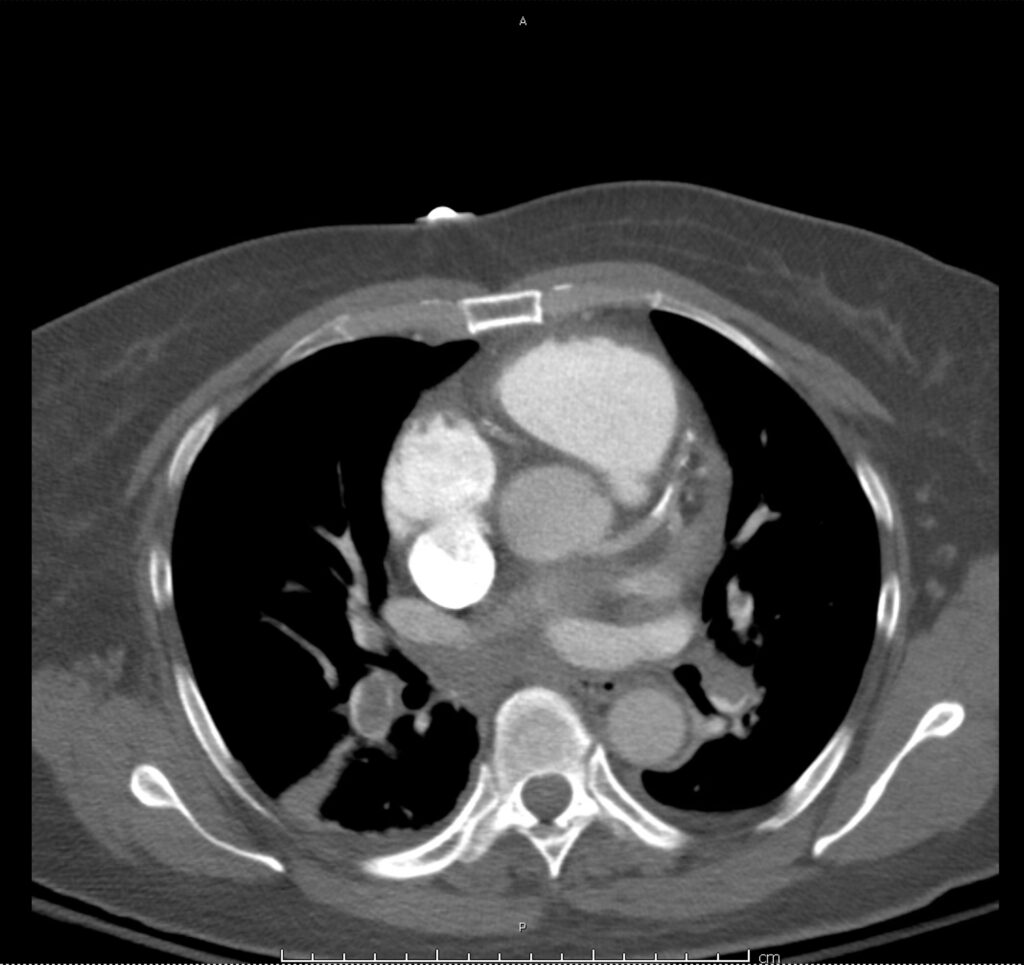

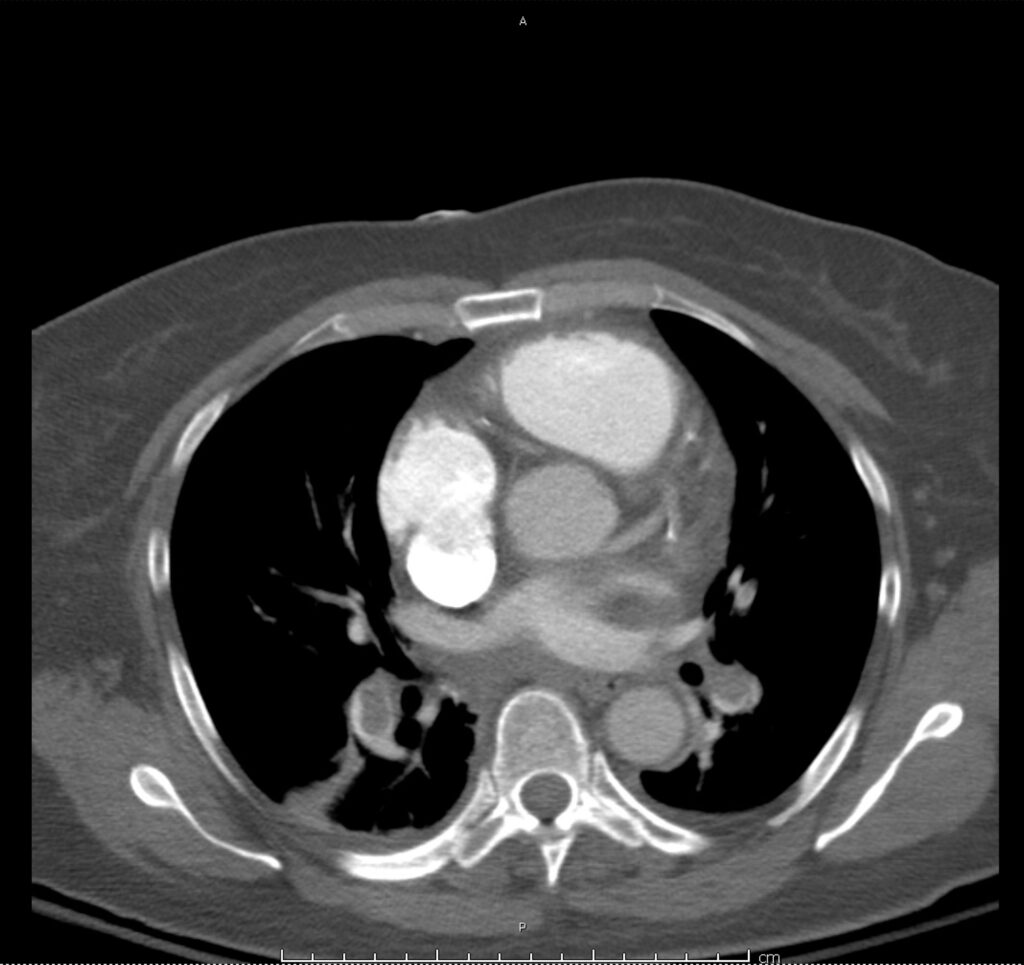

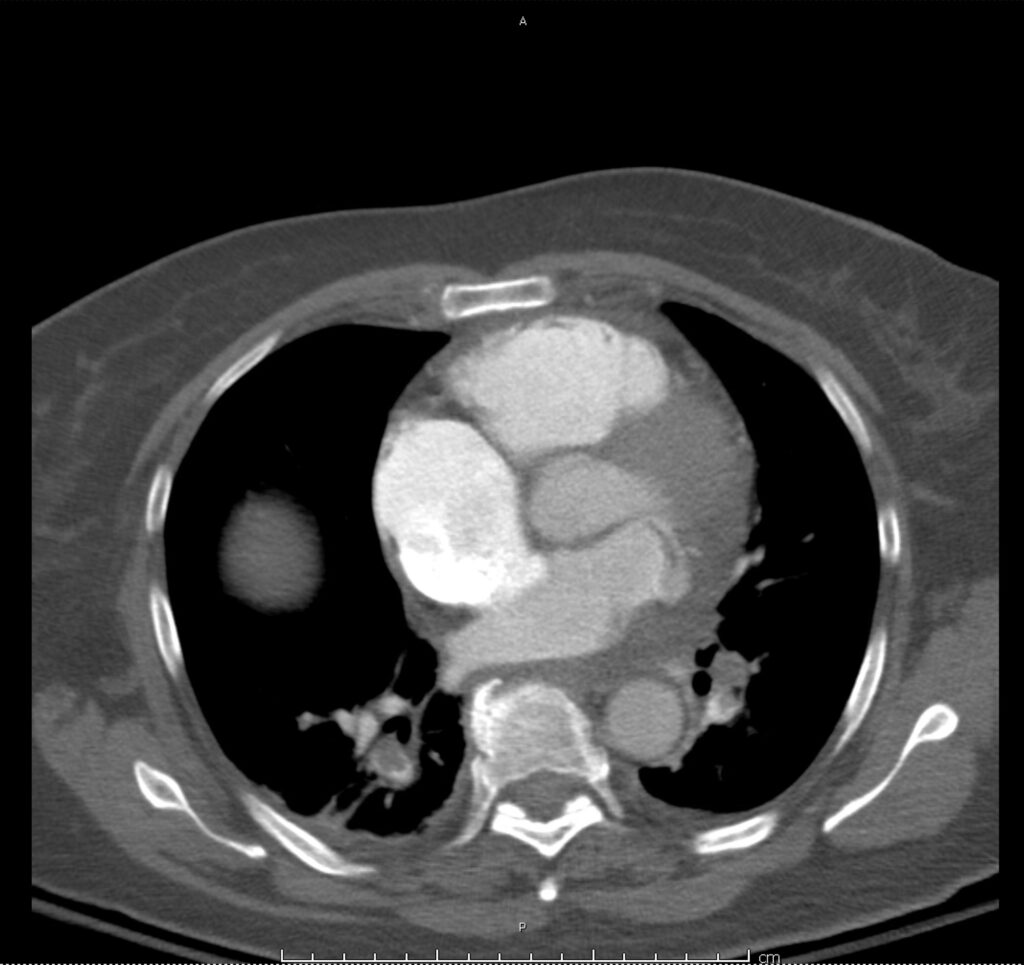

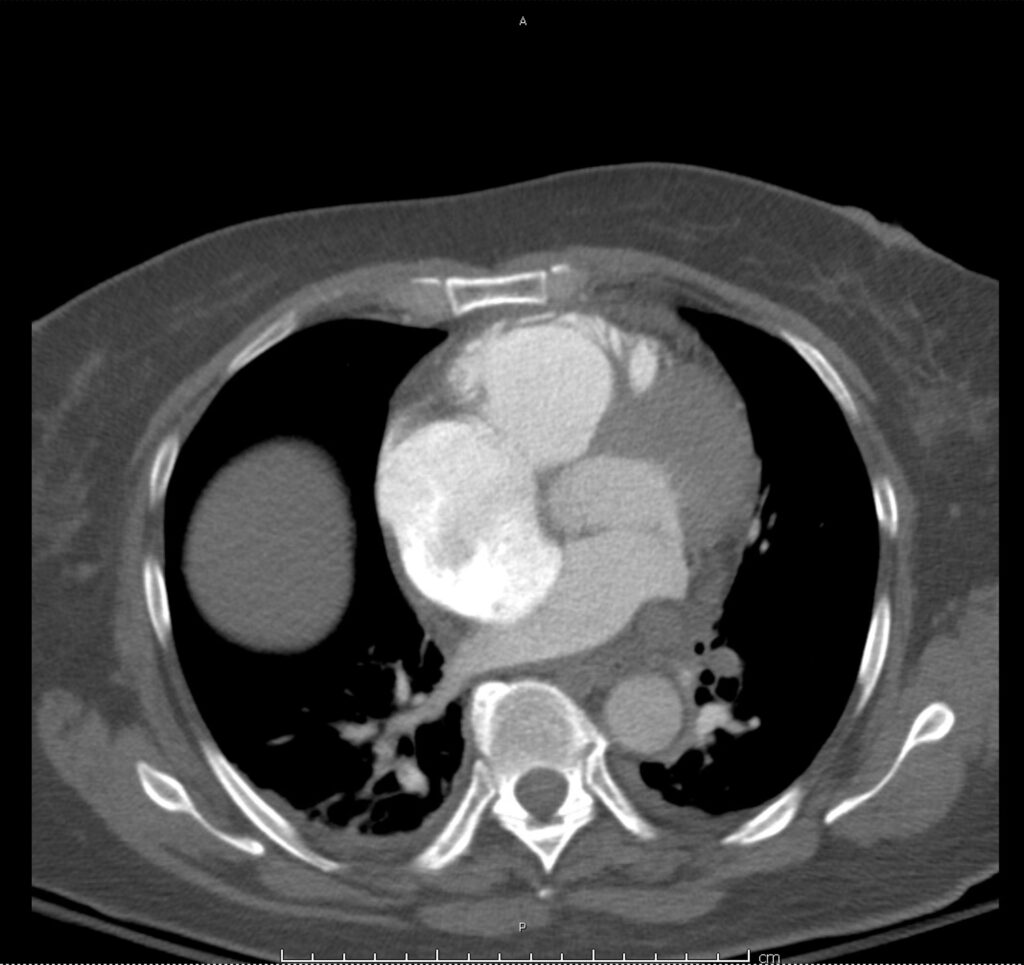

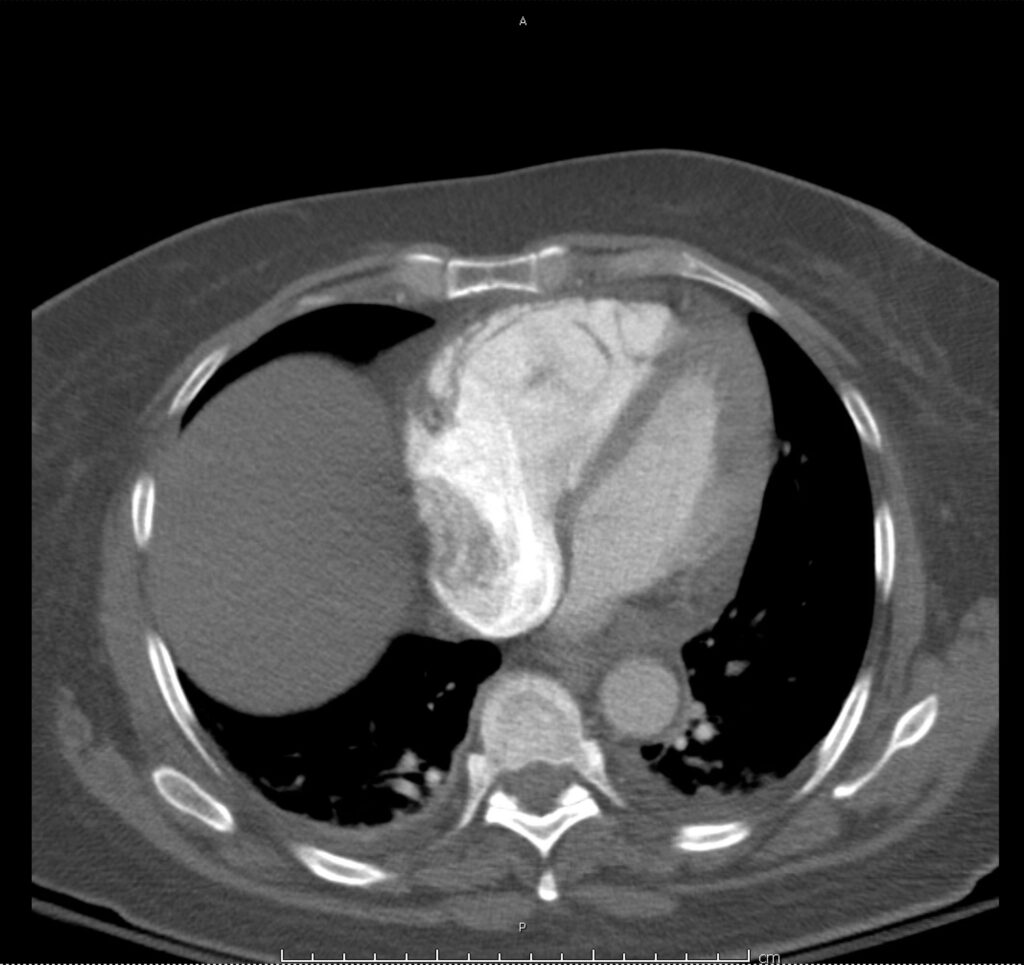

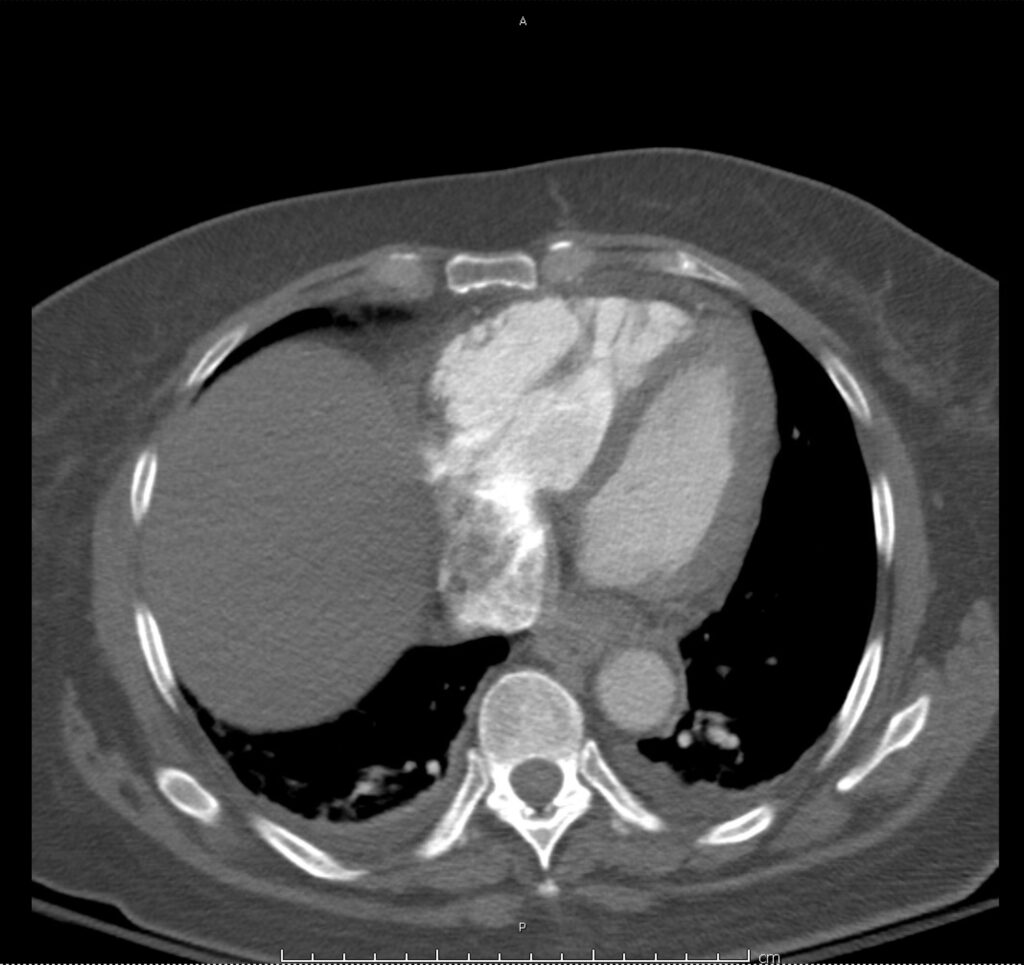

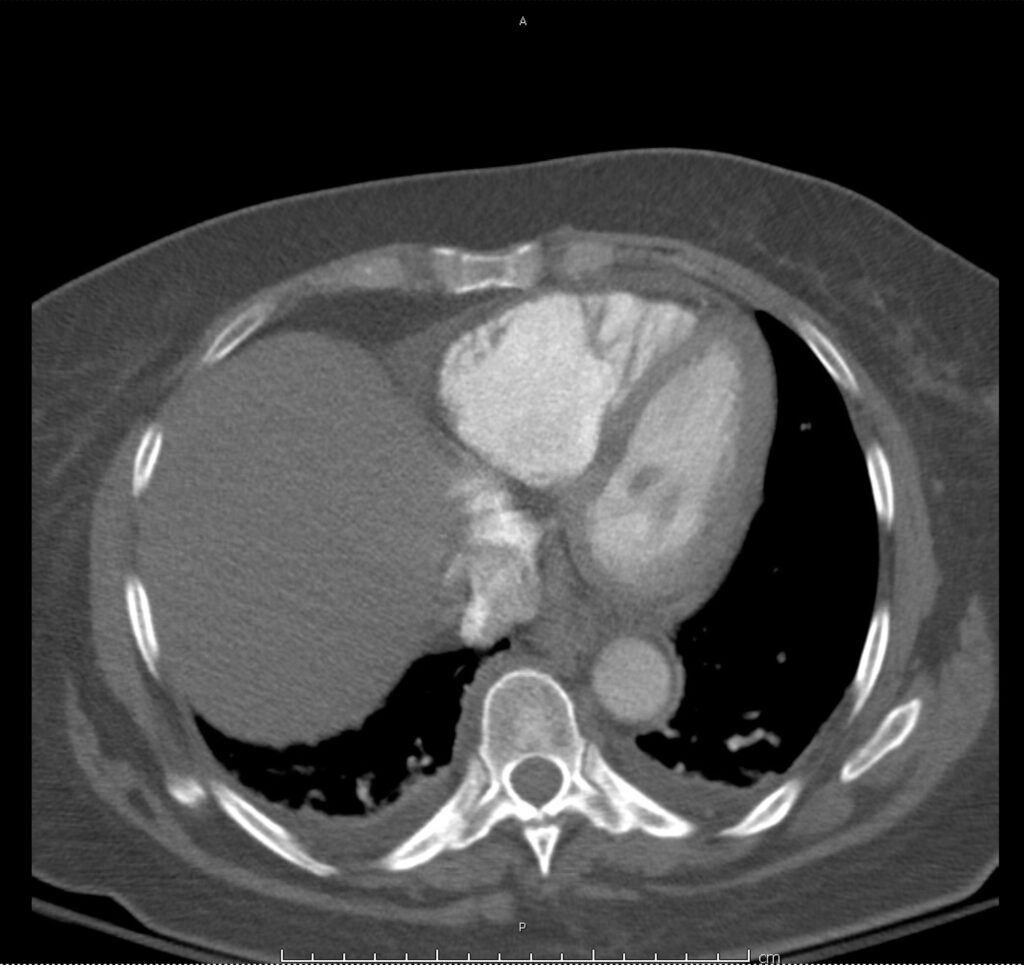

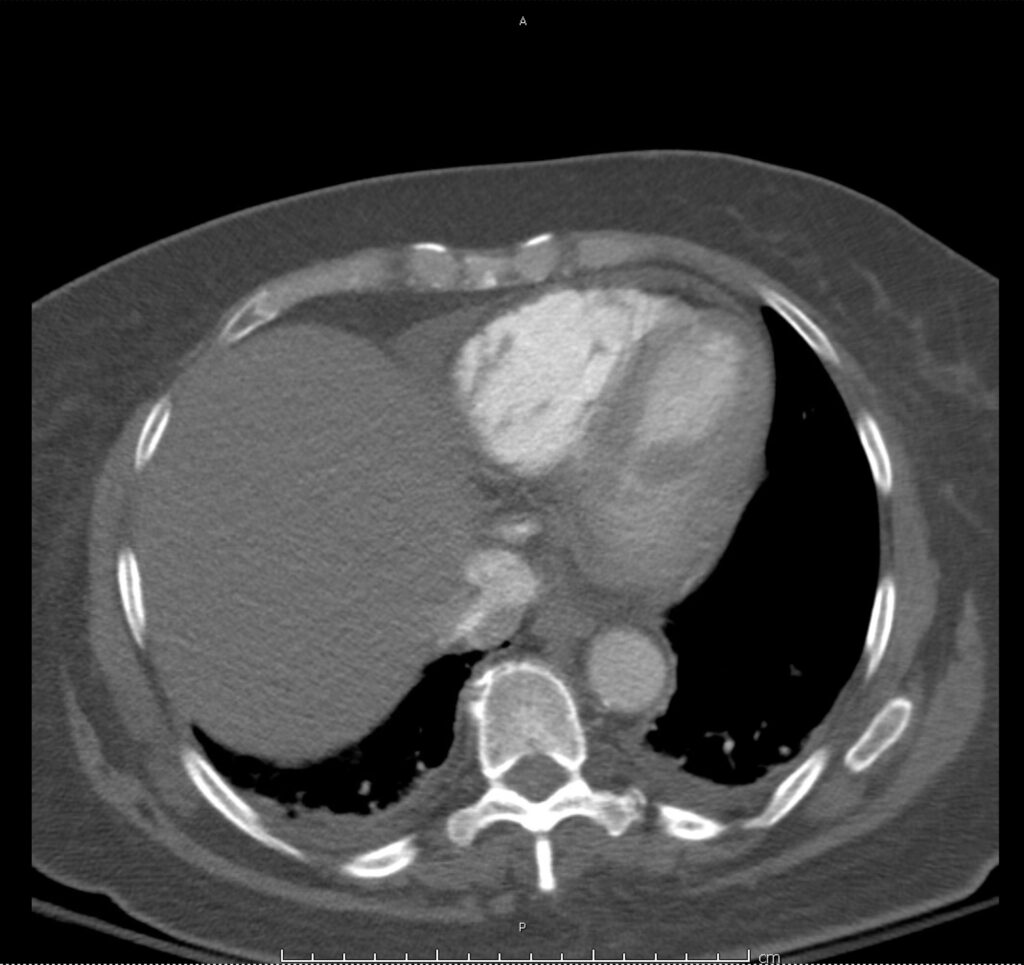

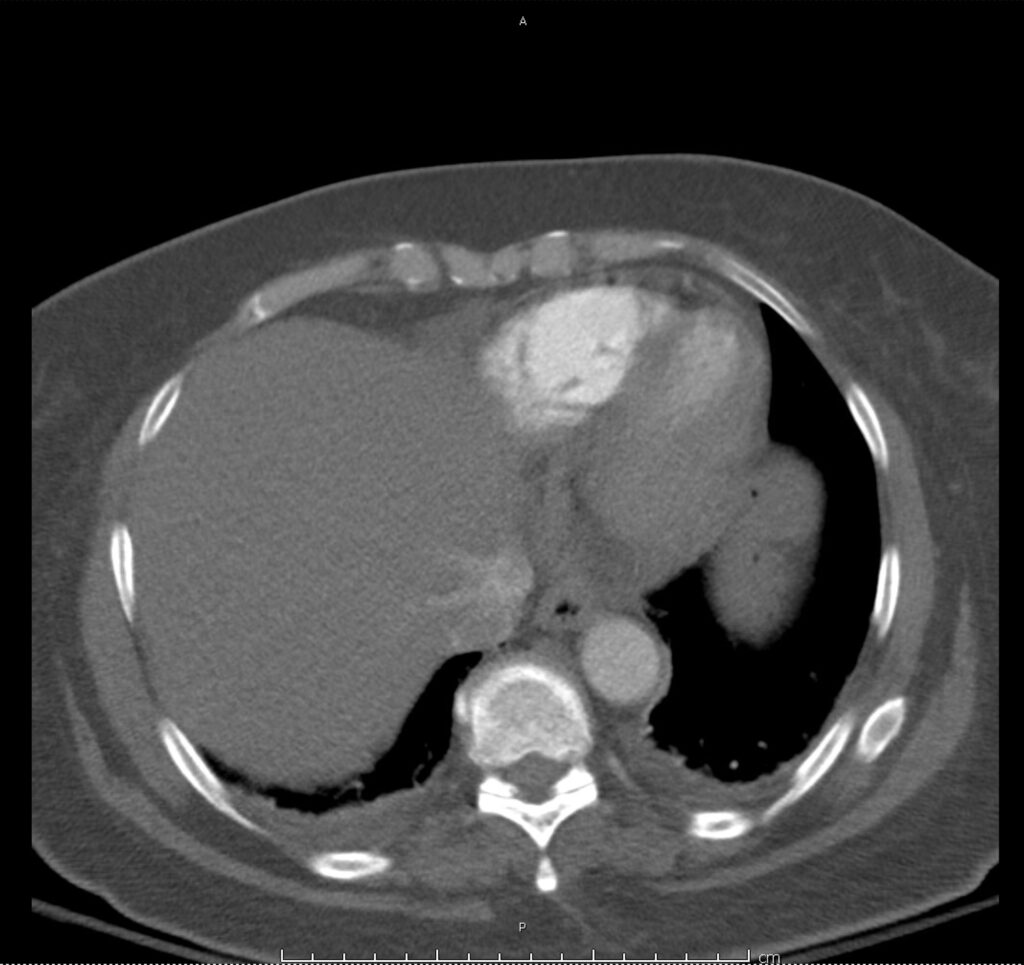

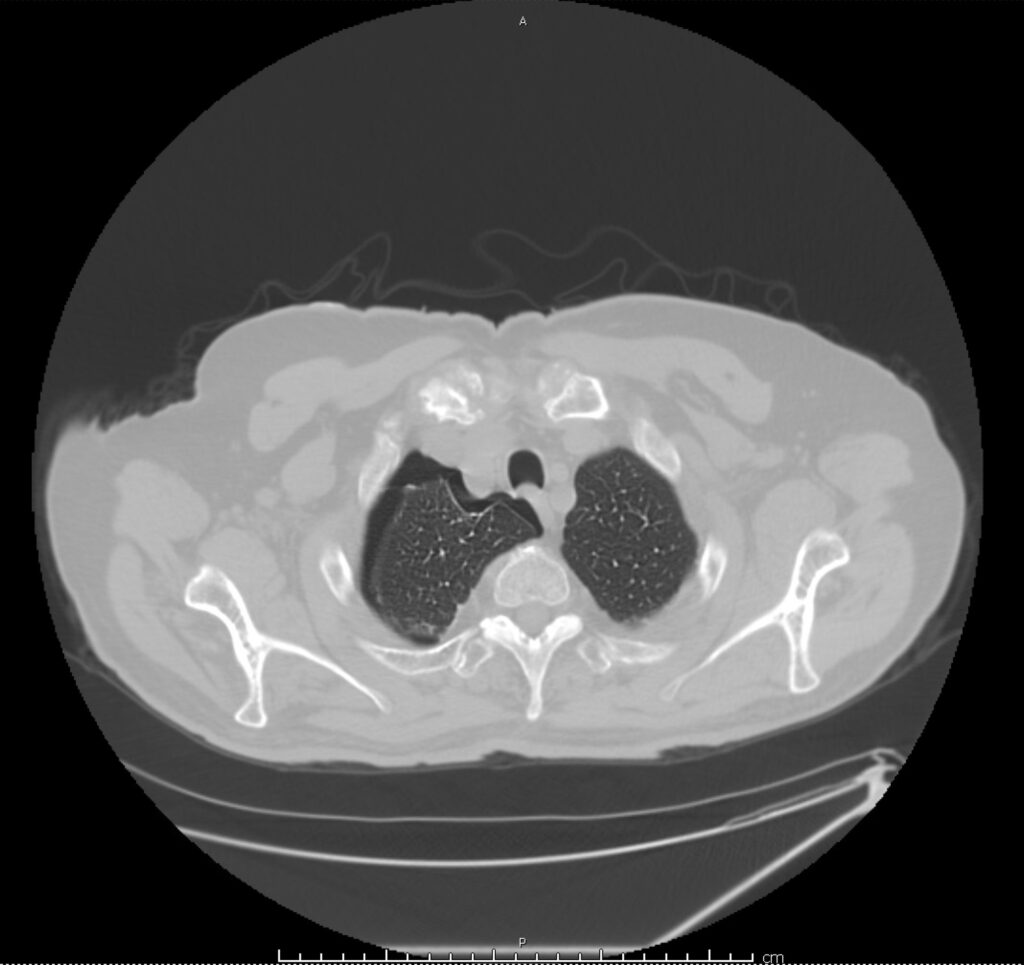

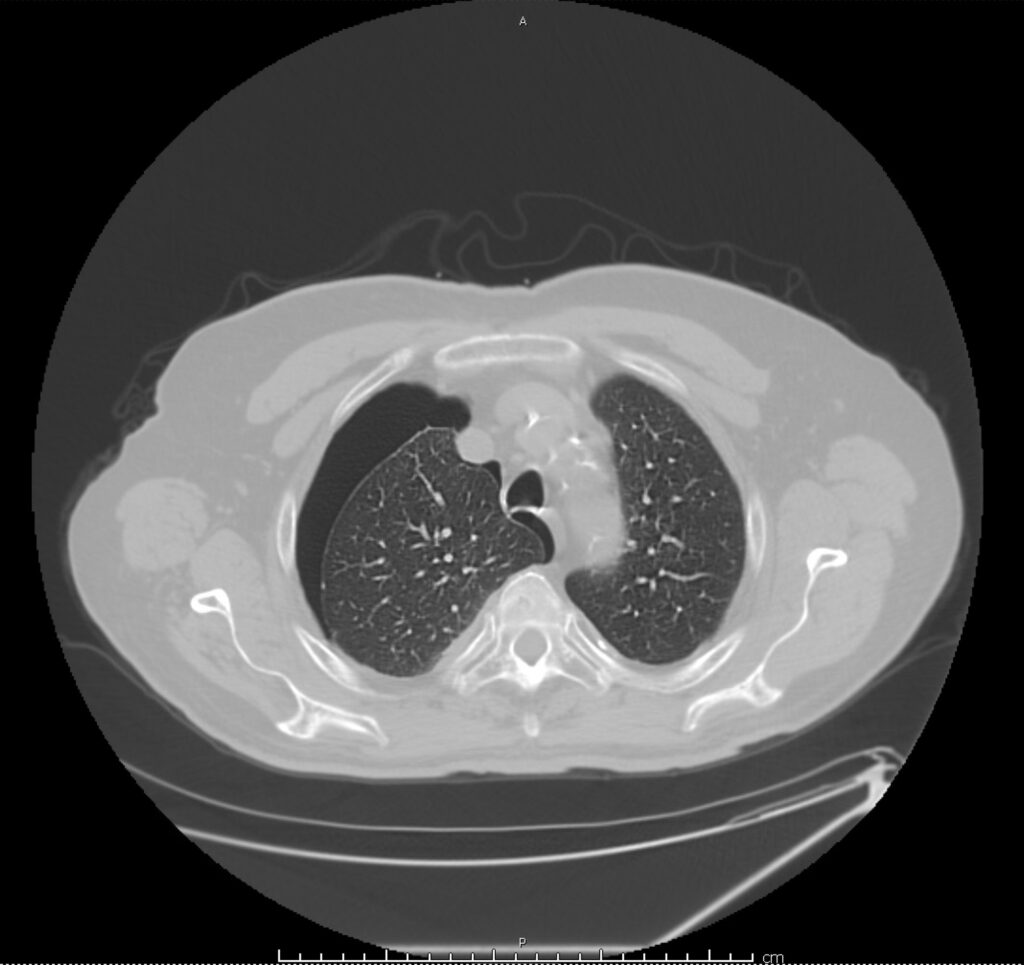

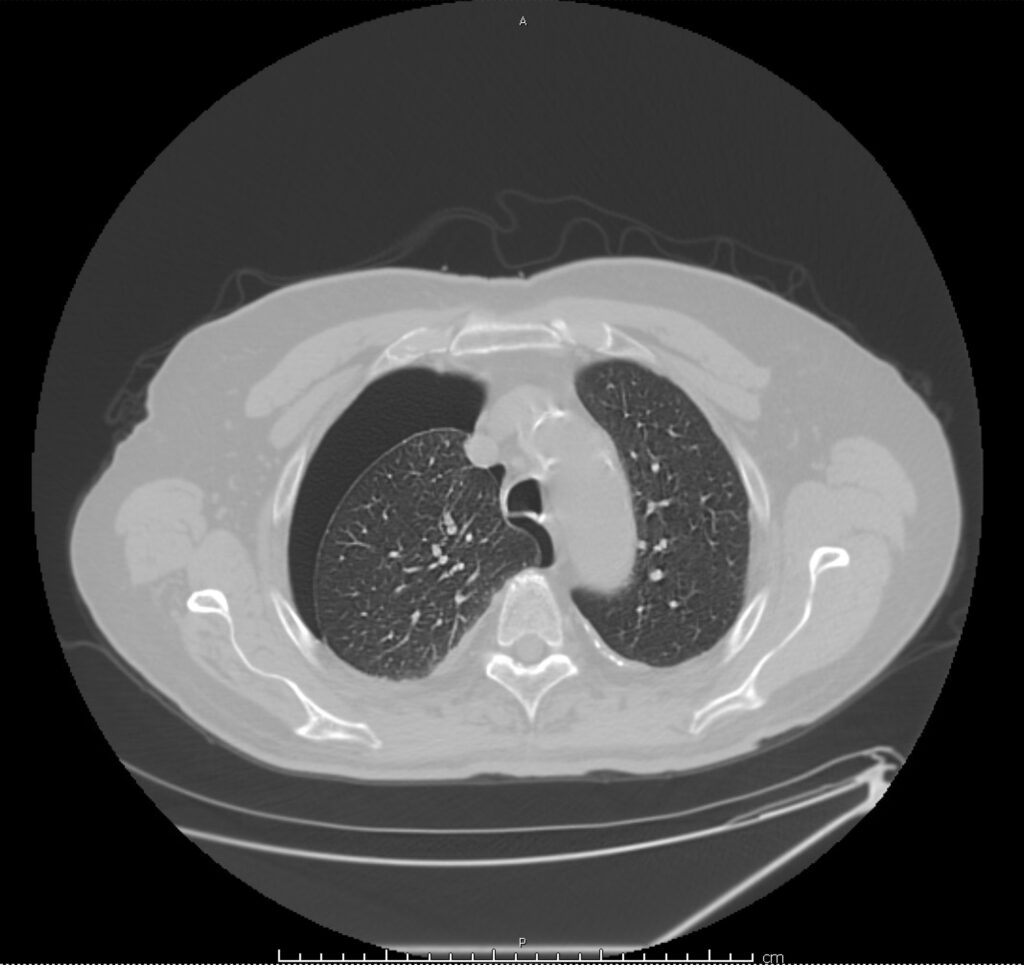

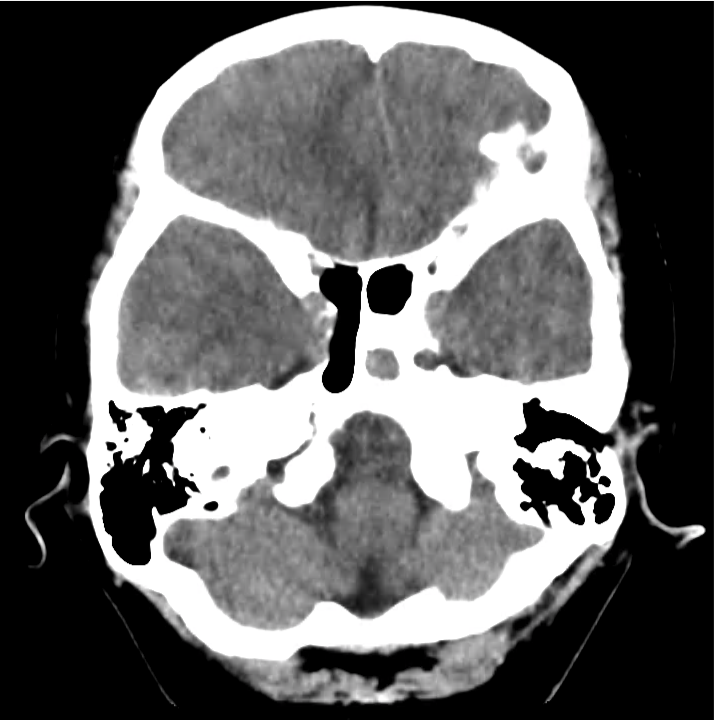

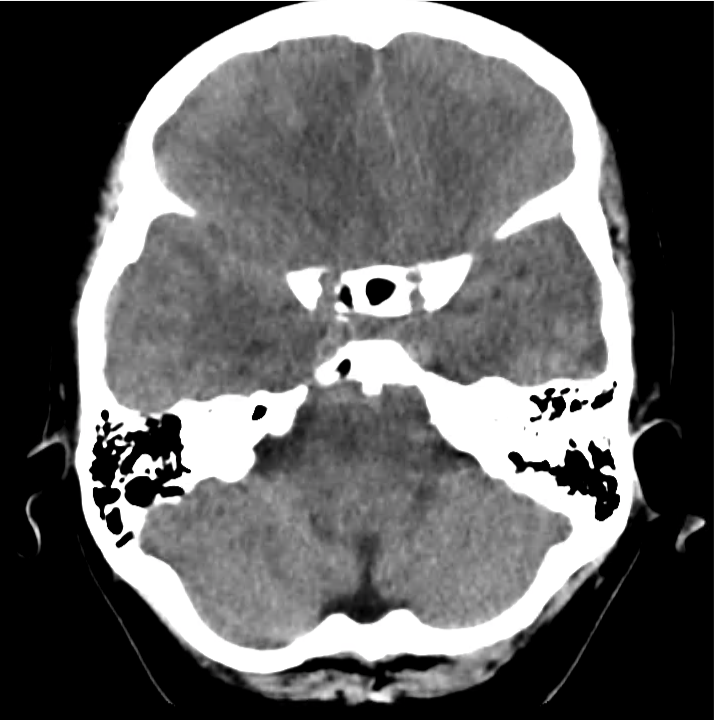

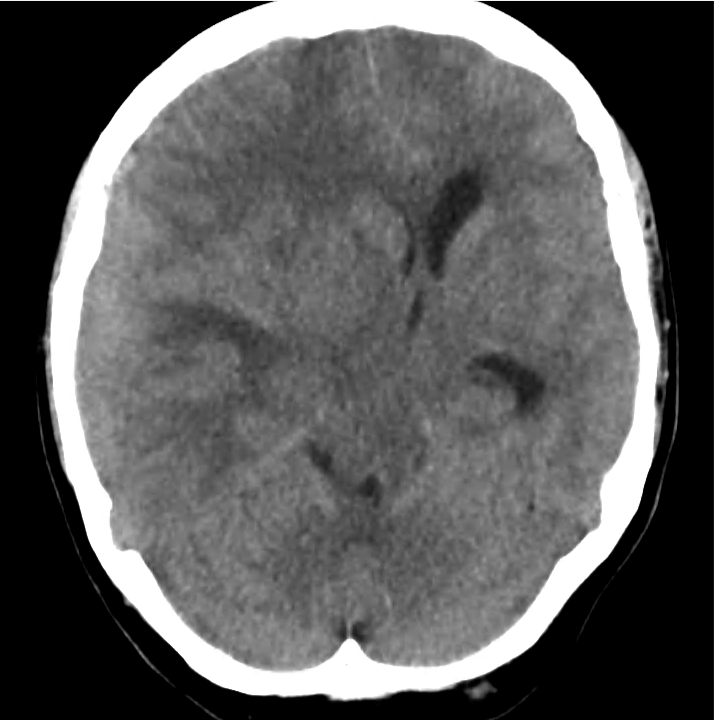

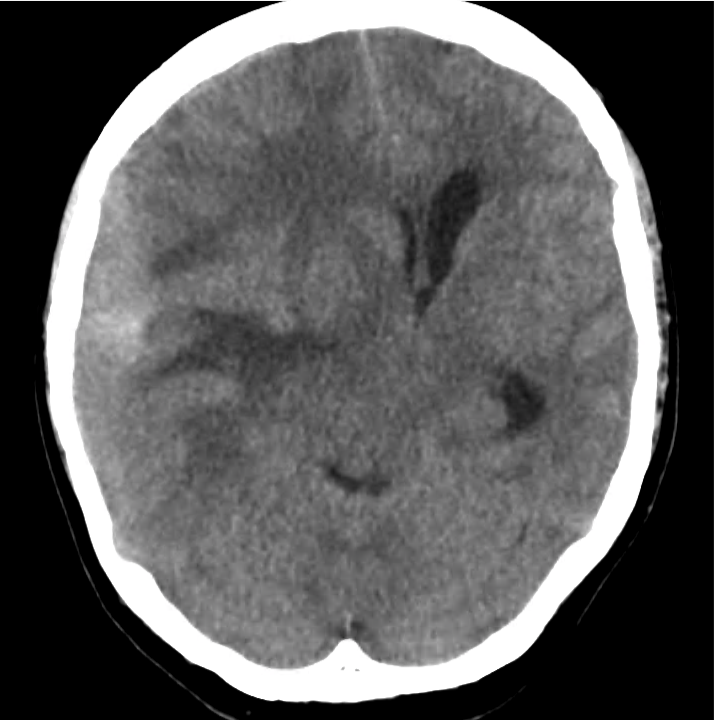

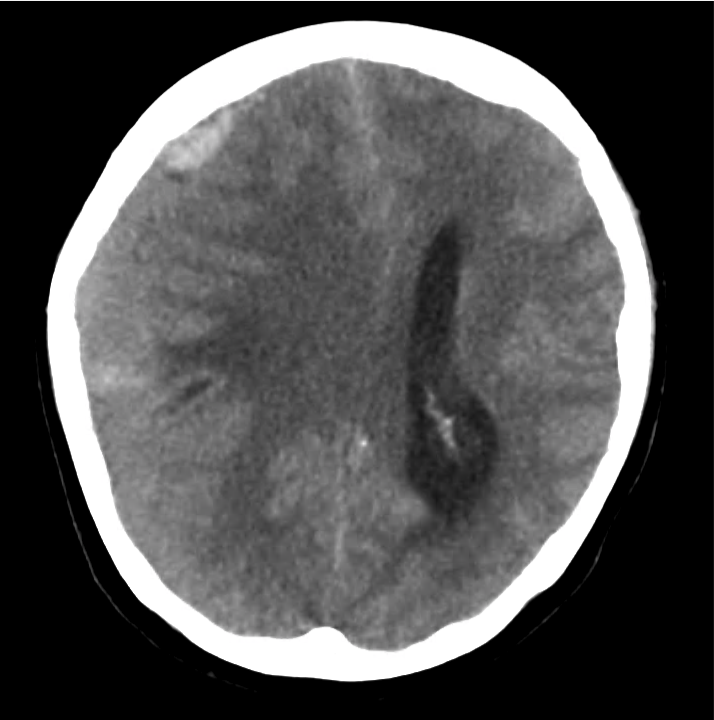

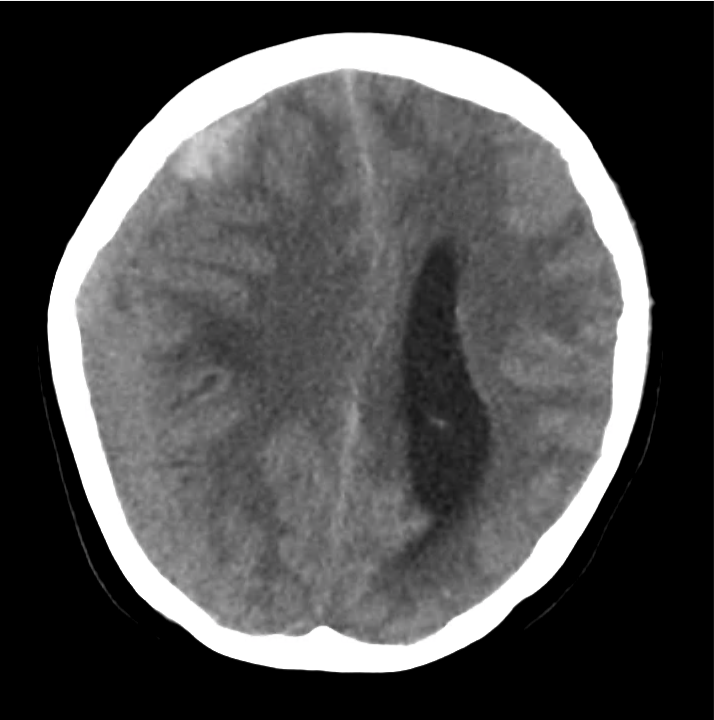

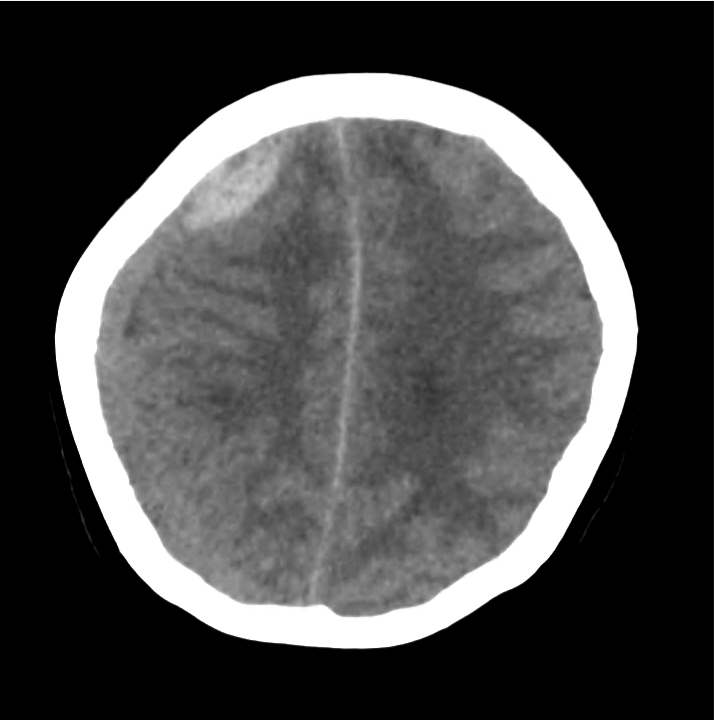

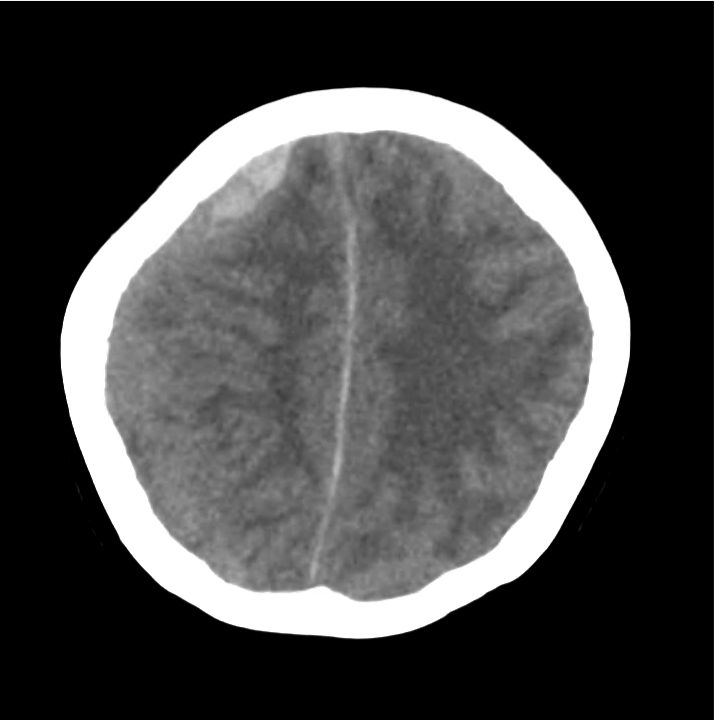

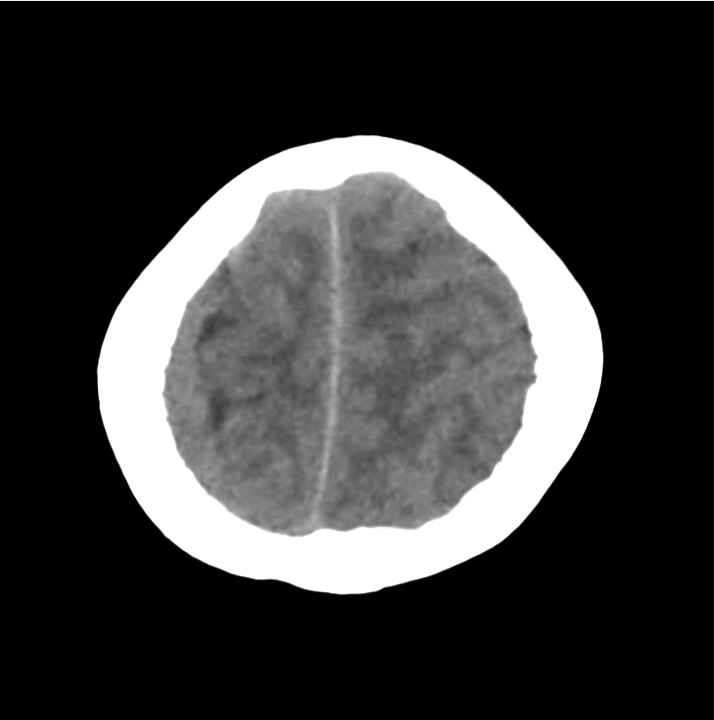

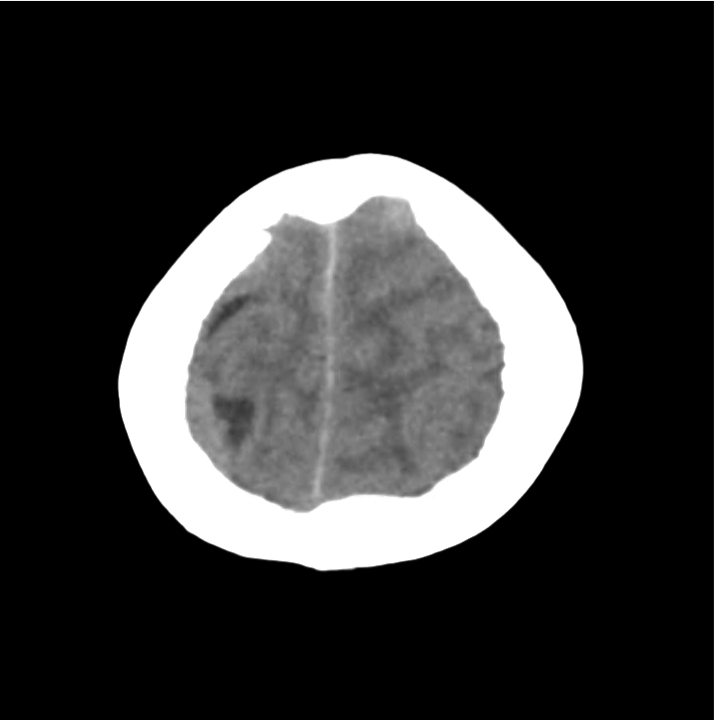

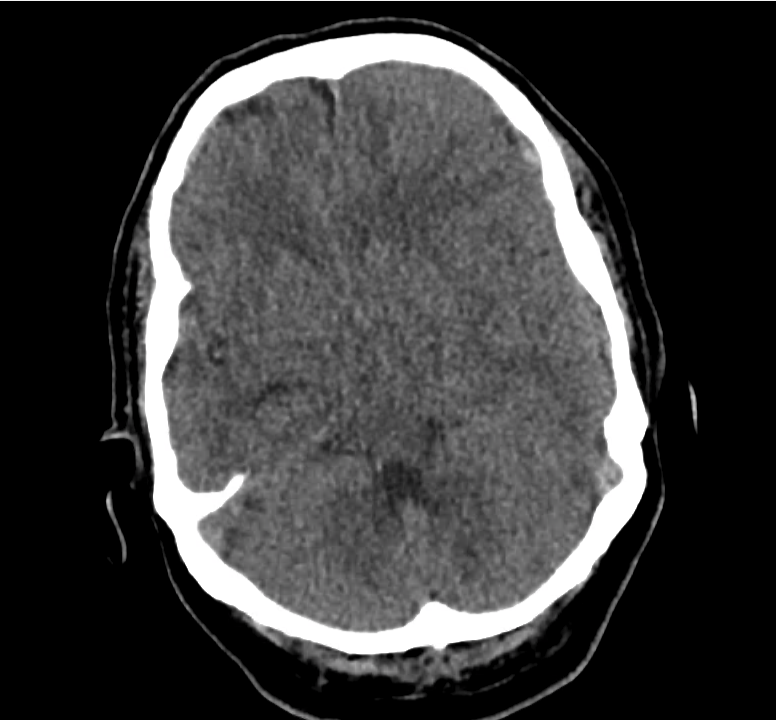

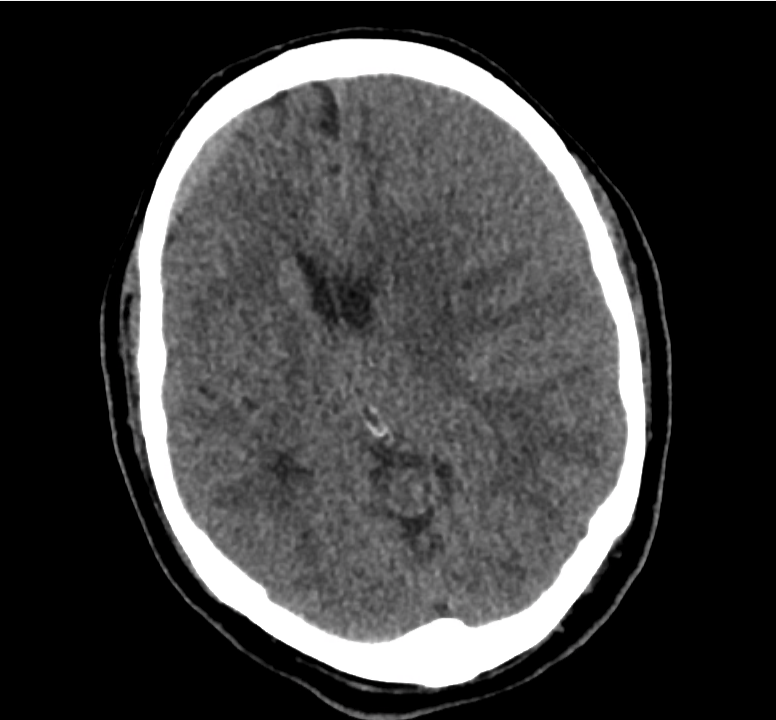

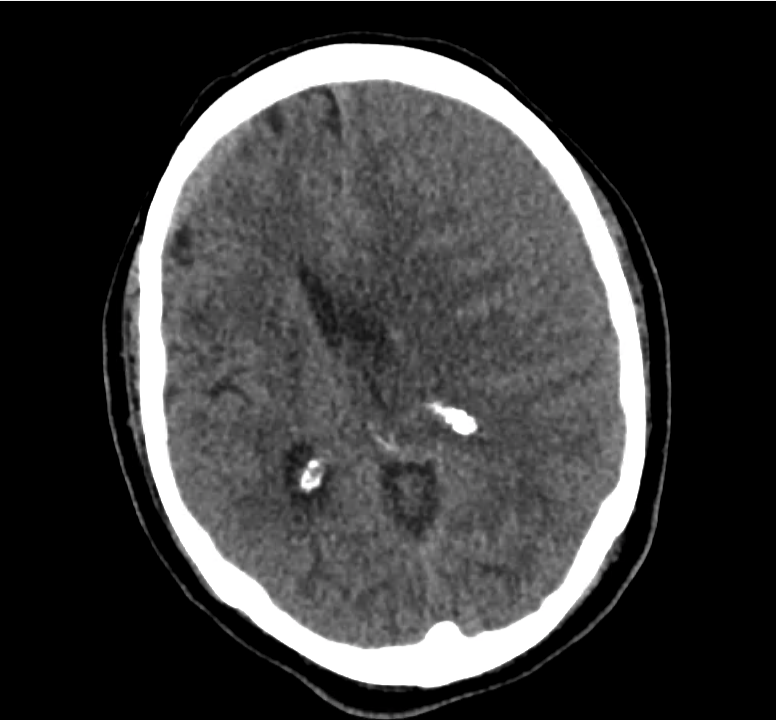

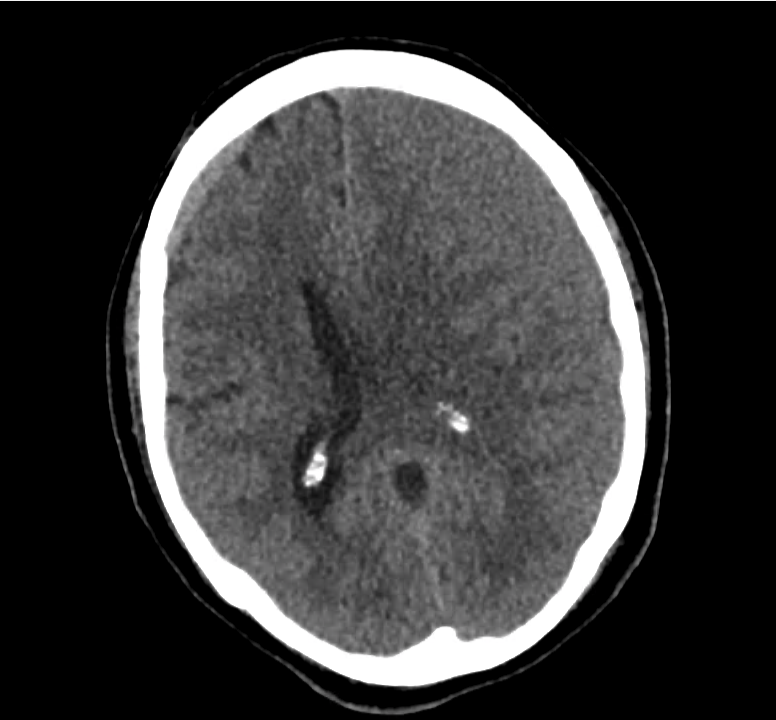

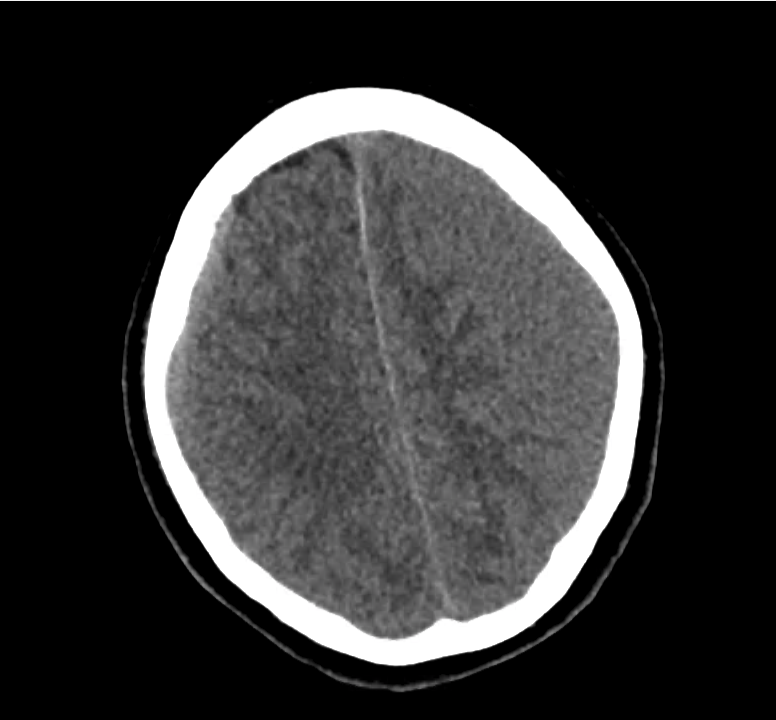

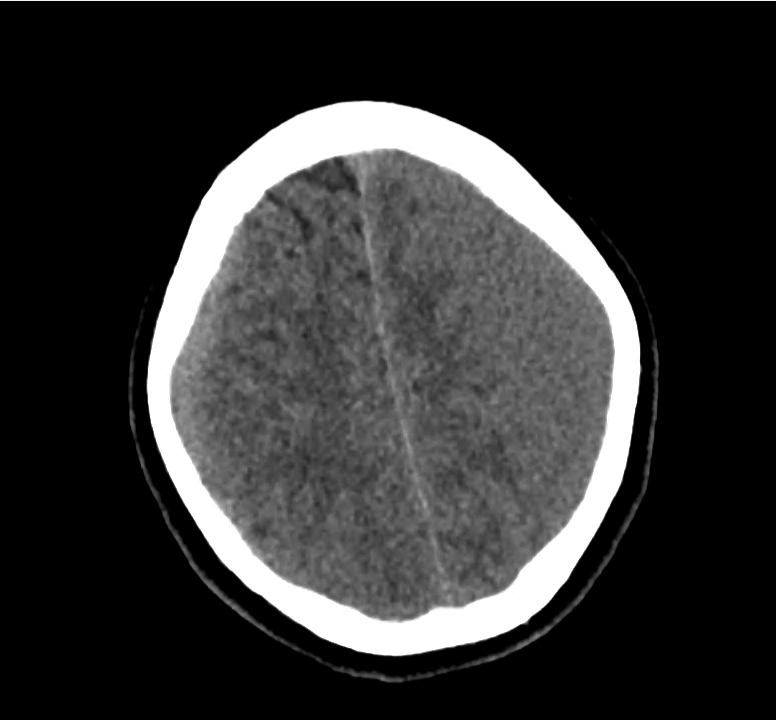

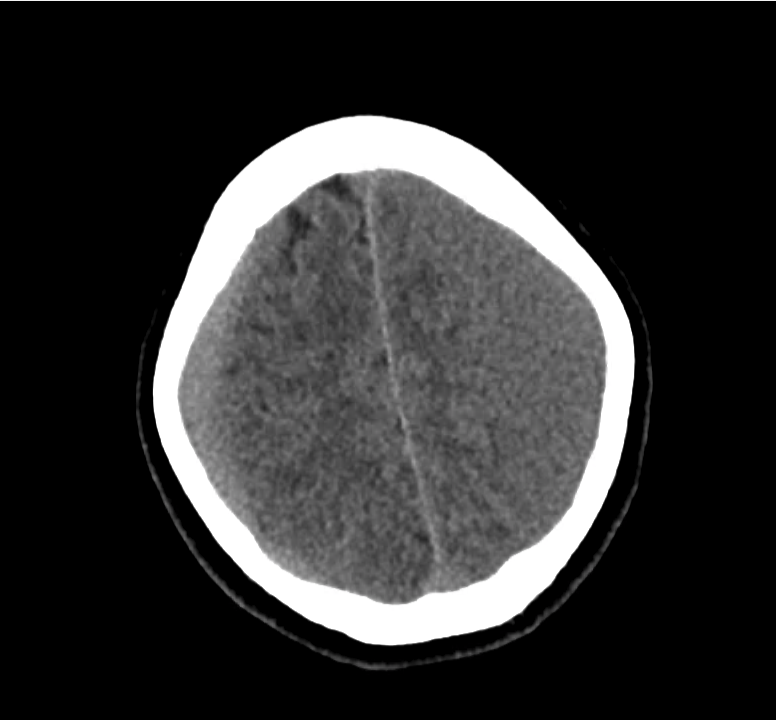

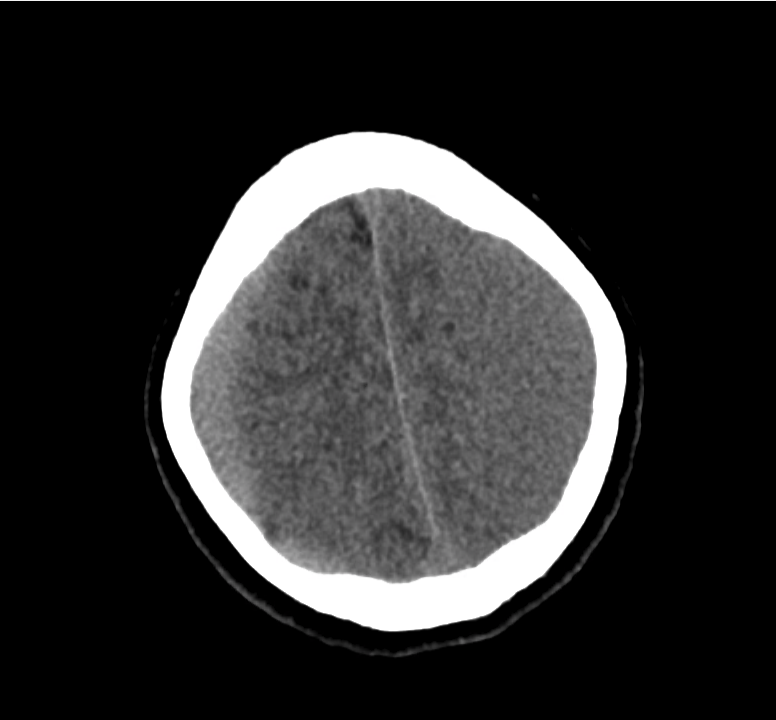

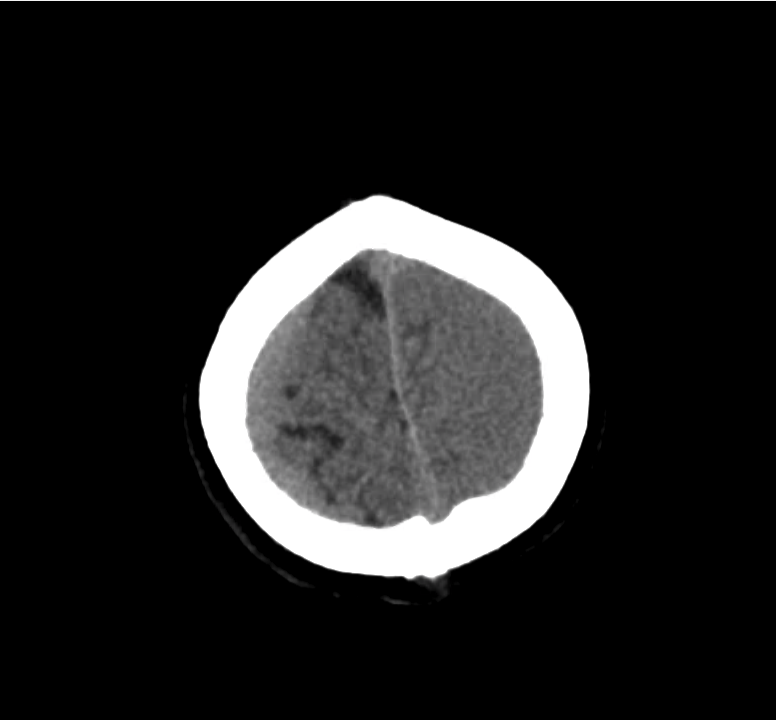

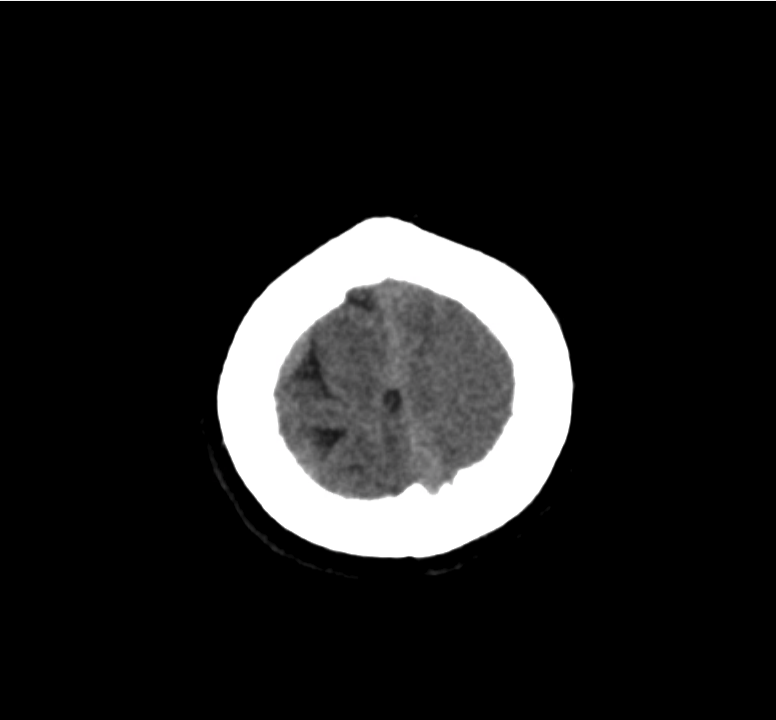

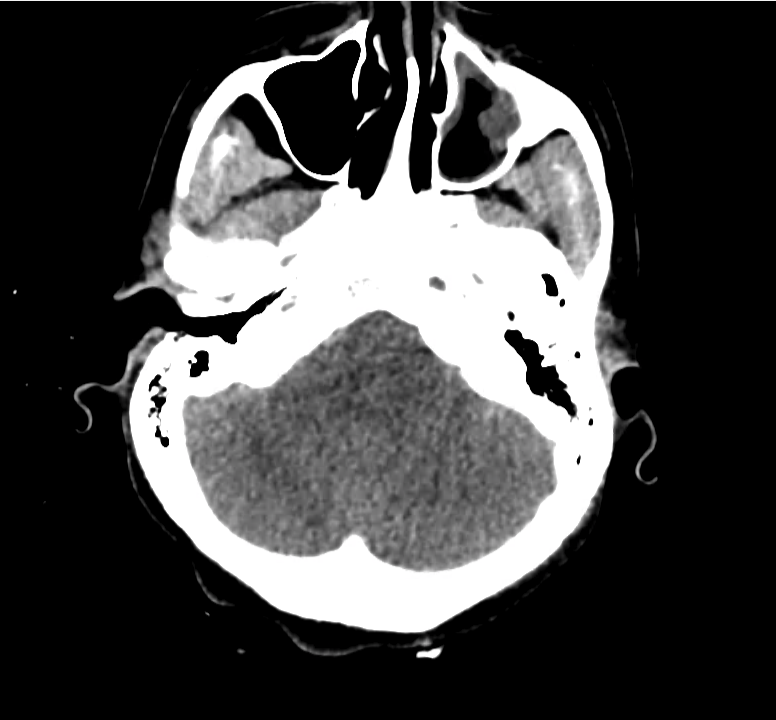

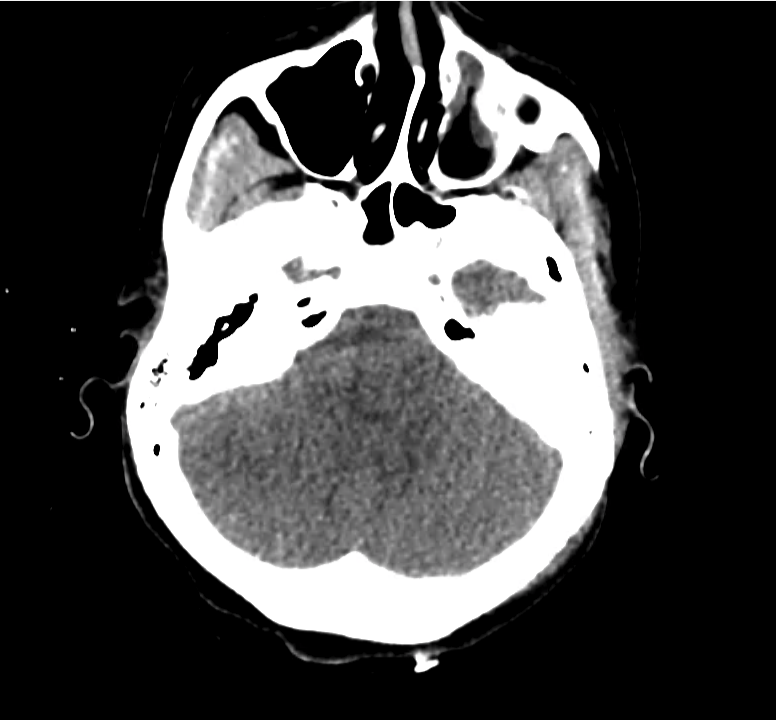

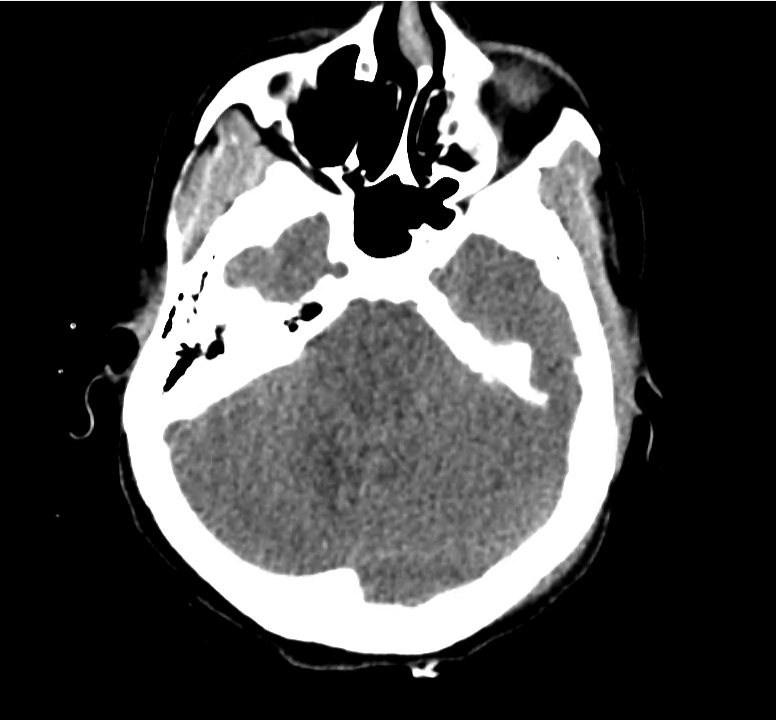

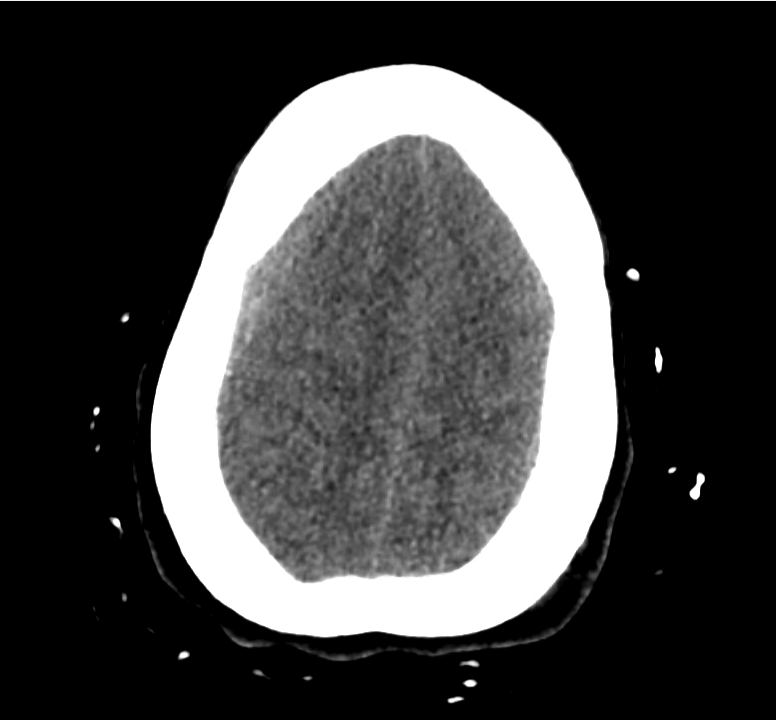

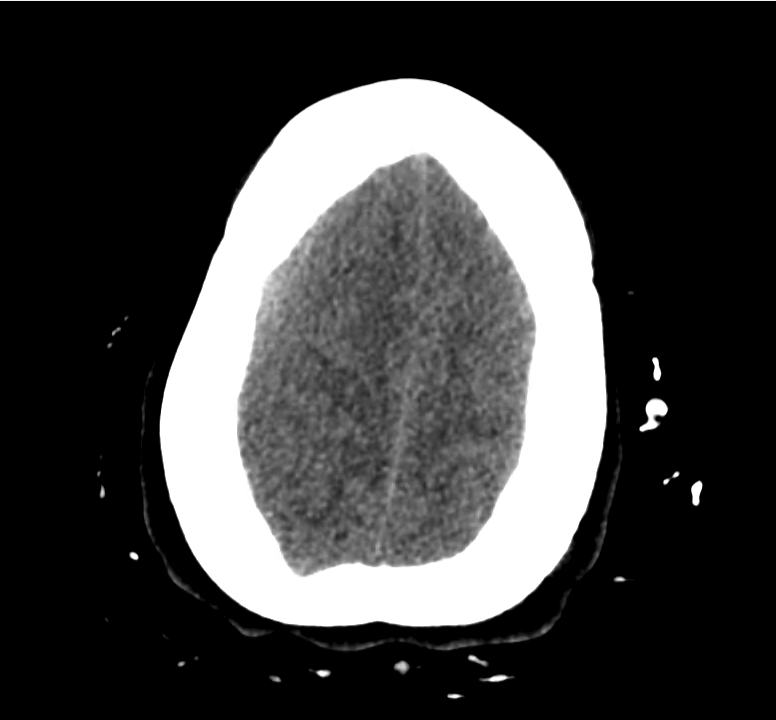

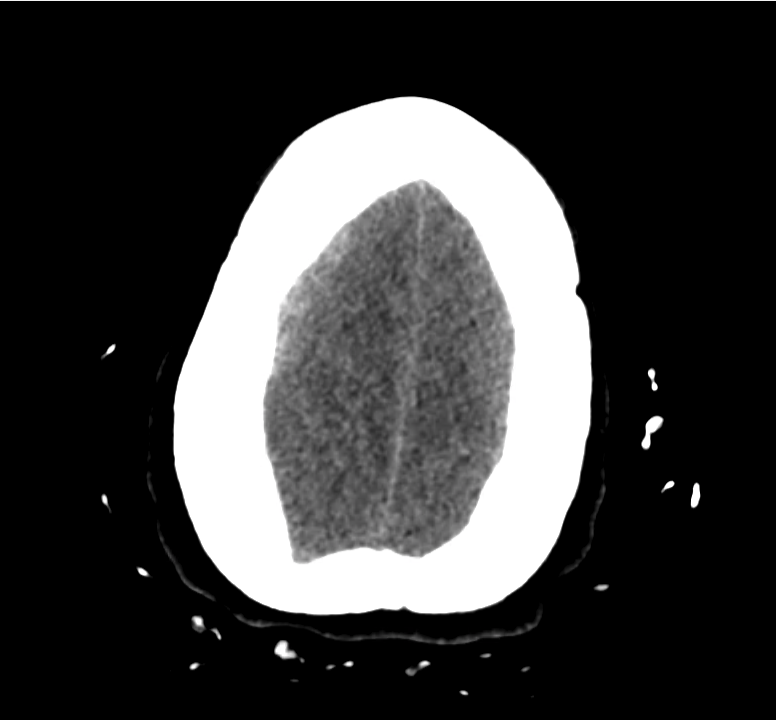

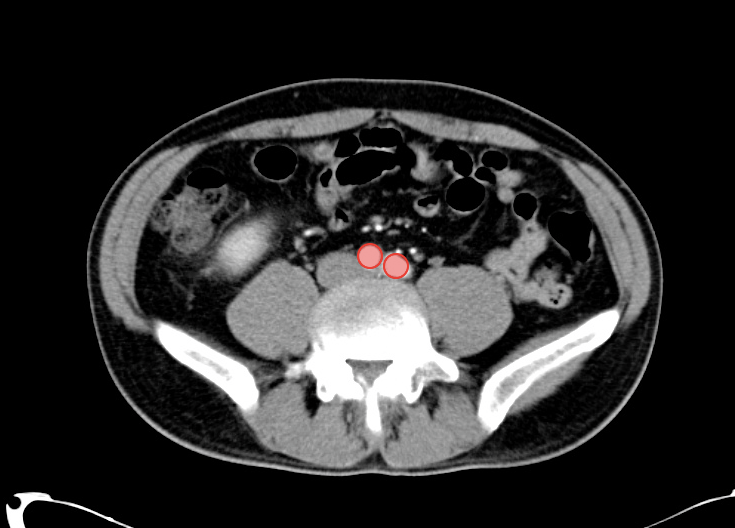

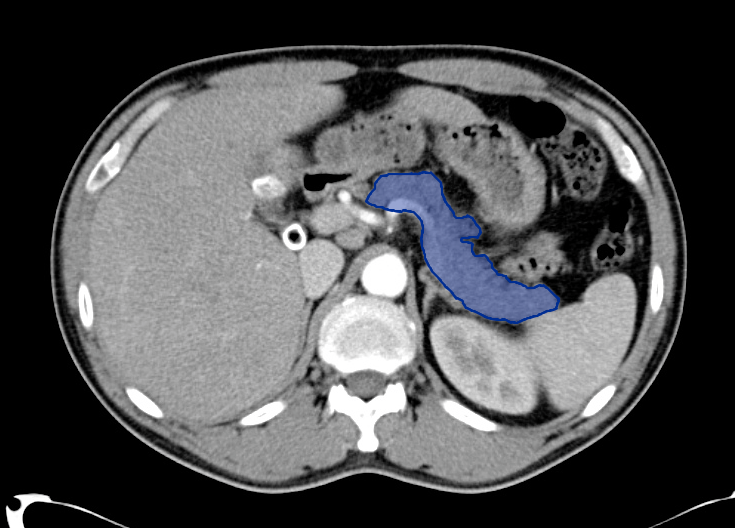

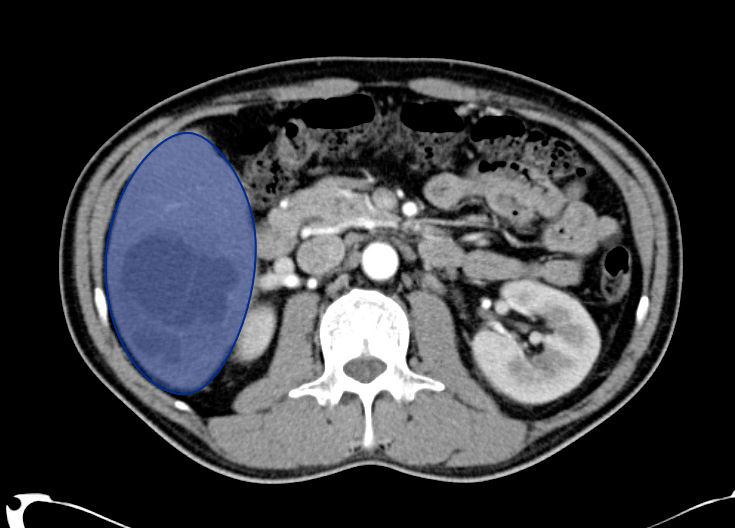

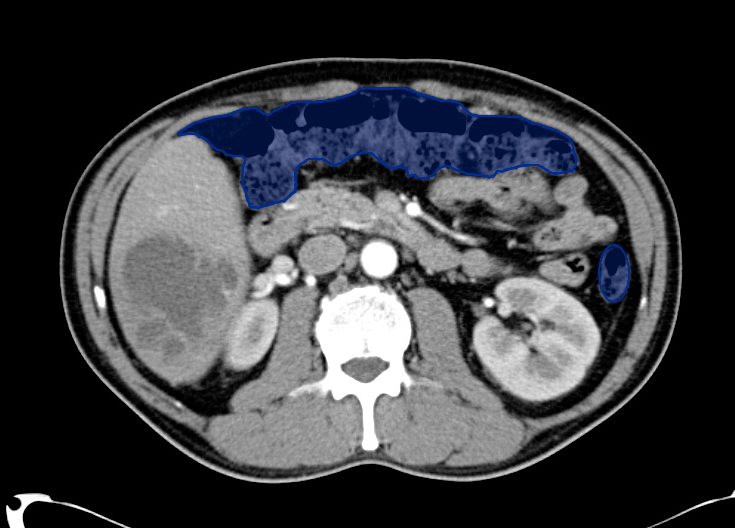

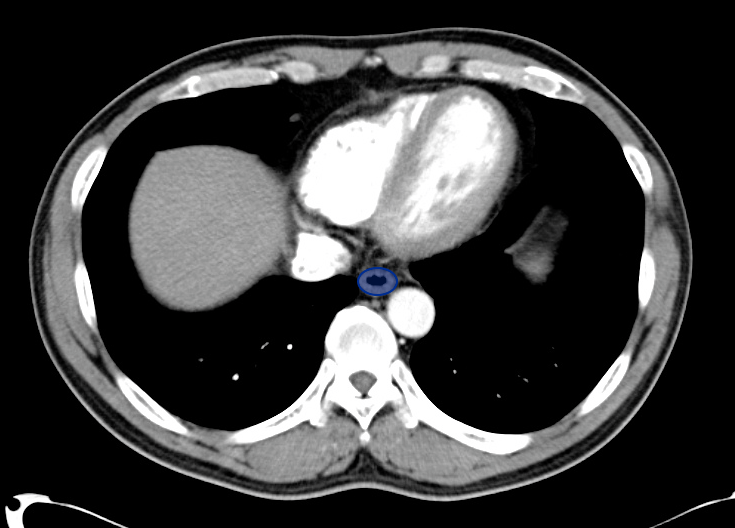

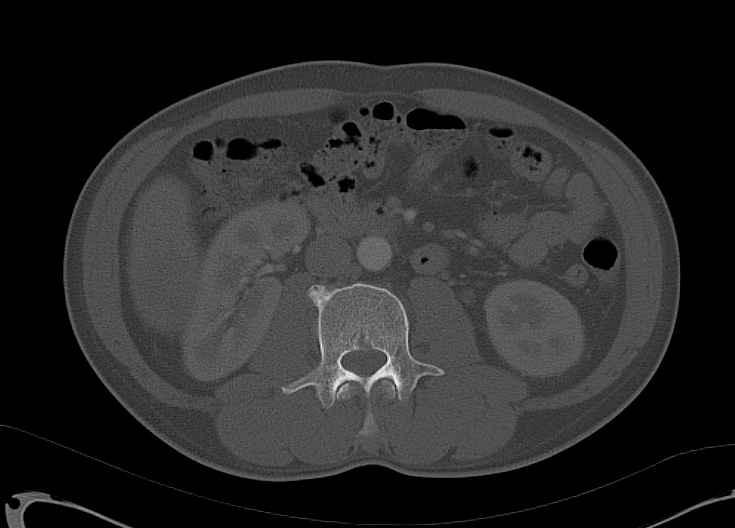

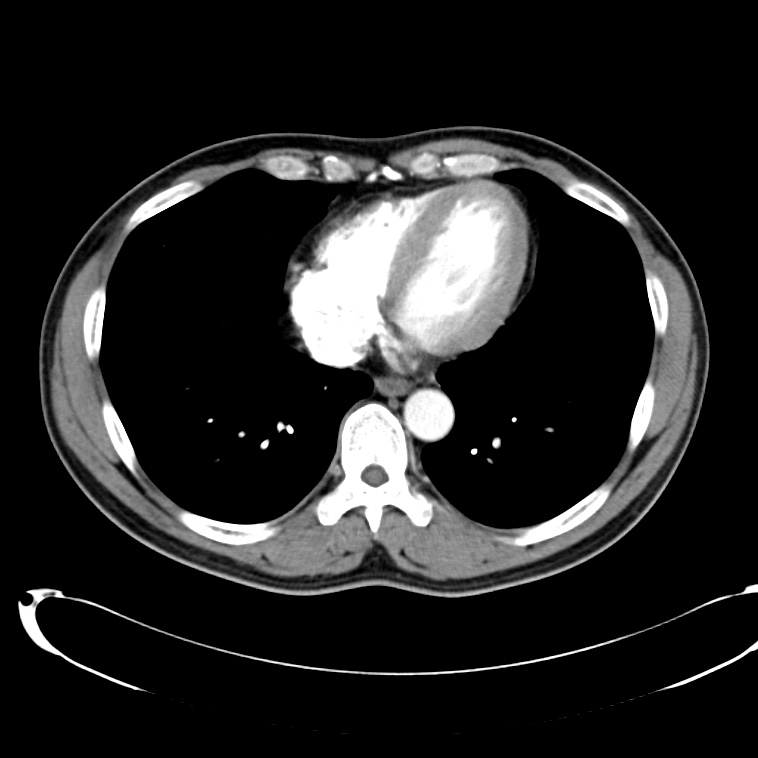

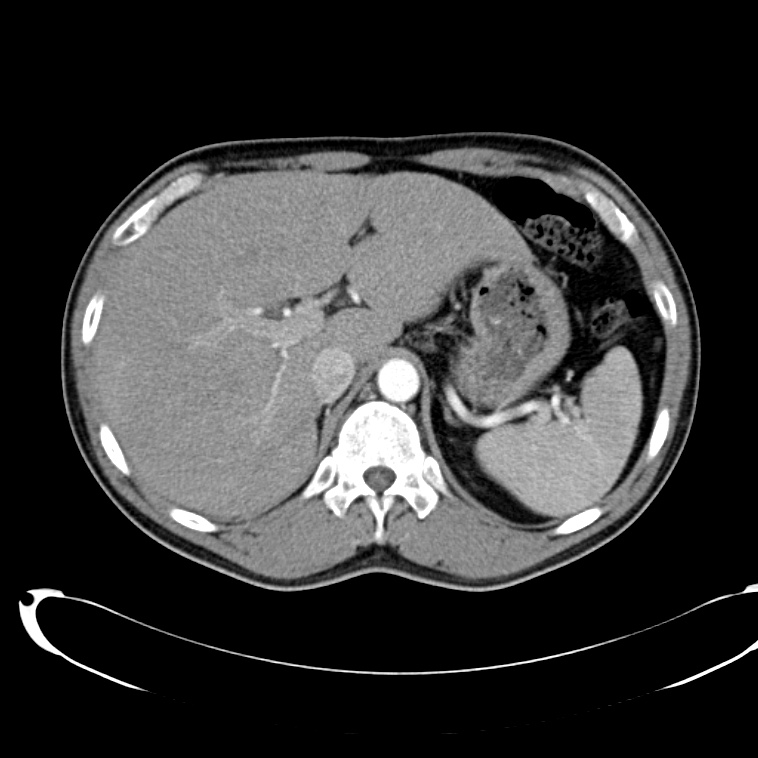

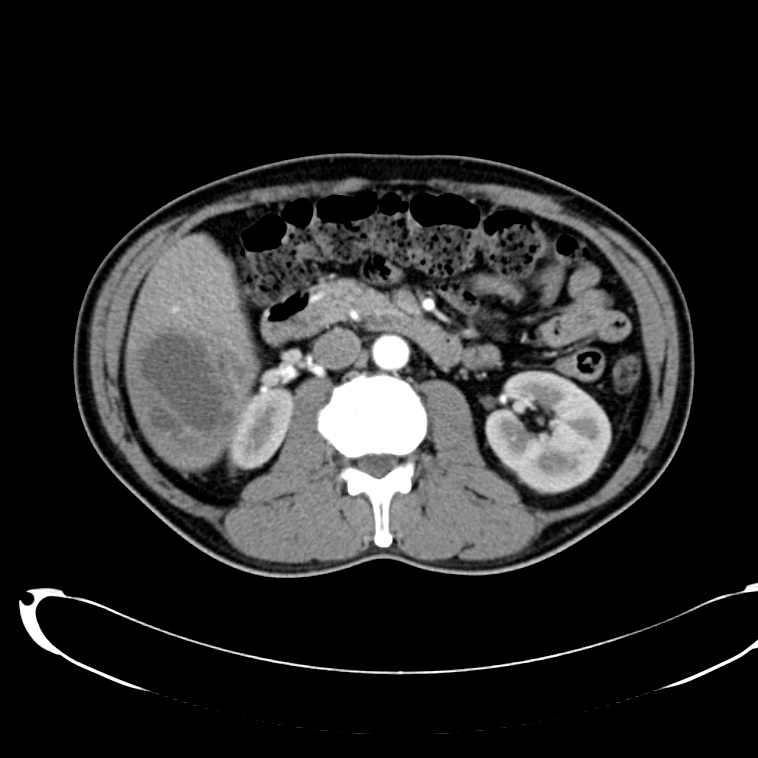

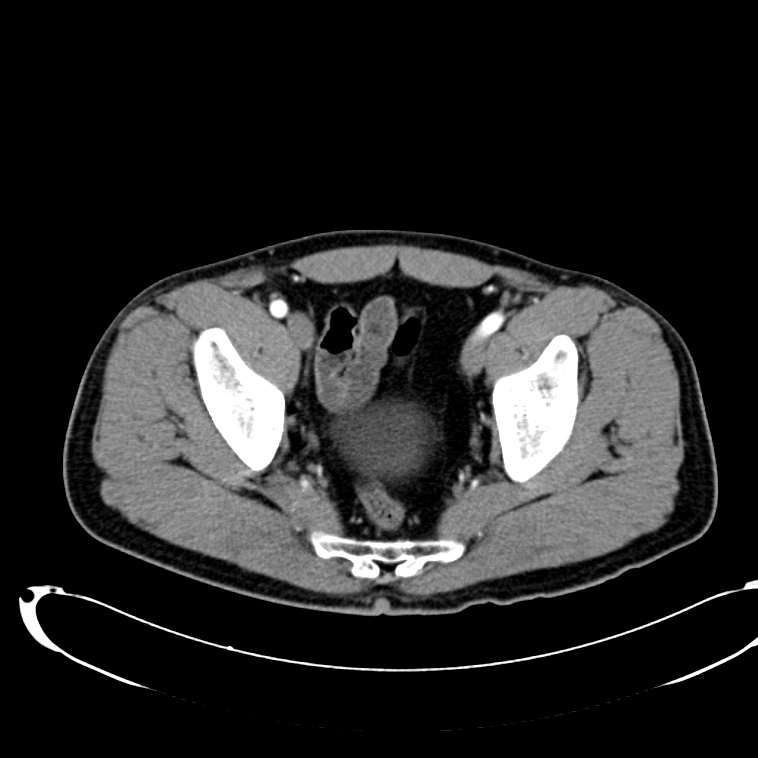

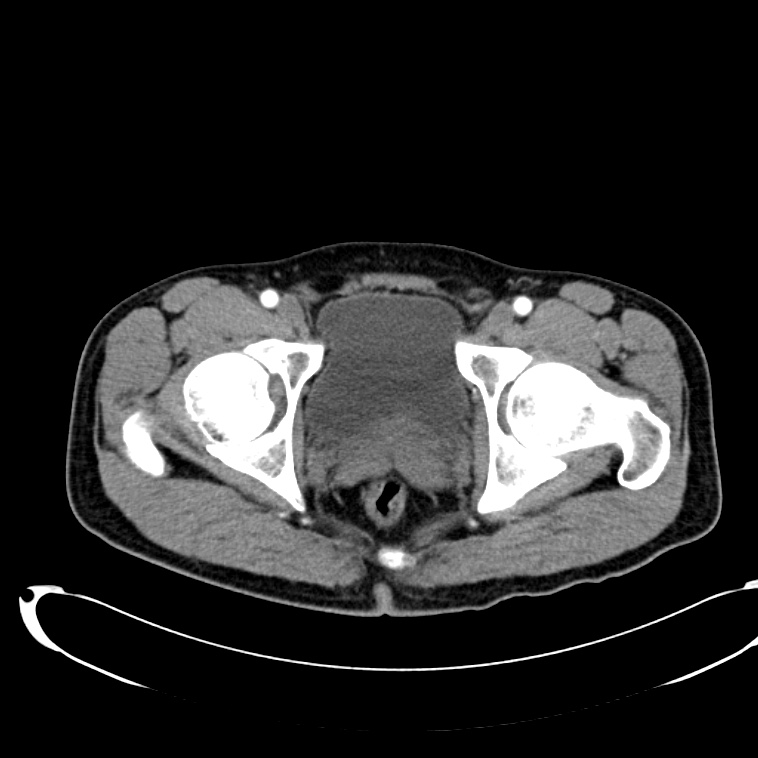

Example #3

CT Head Interpretation

Subdural hematoma with significant herniation

References

- Perron A. How to read a head CT scan. Emergency Medicine. 2008.

- Arhami Dolatabadi A, Baratloo A, Rouhipour A, et al. Interpretation of Computed Tomography of the Head: Emergency Physicians versus Radiologists. Trauma Mon. 2013;18(2):86–89. doi:10.5812/traumamon.12023.