Brief H&P

48F with a history of Grave disease (off medications for 4 months), presenting with palpitations. Noted gradual onset of palpitations while at rest, describing a pounding sensation lasting 3-4 hours and persistent (though improved) on presentation. Symptoms not associated with chest pain, shortness of breath, loss of consciousness, nor triggered by exertion. She reported a history of 8-10 episodes in the past for which she did not seek medical attention. Review of systems notable only for heat intolerance.

On physical examination, vital signs were notable for tachycardia (HR 138bpm). No alteration in mental status, murmur, tremor or hyperreflexia appreciated.

Labs

- Hb: 14.7

- Urine hCG: negative

- TSH: <0.01

- Total T3: 311ng/dL

- Free T4: 2.64ng/dL

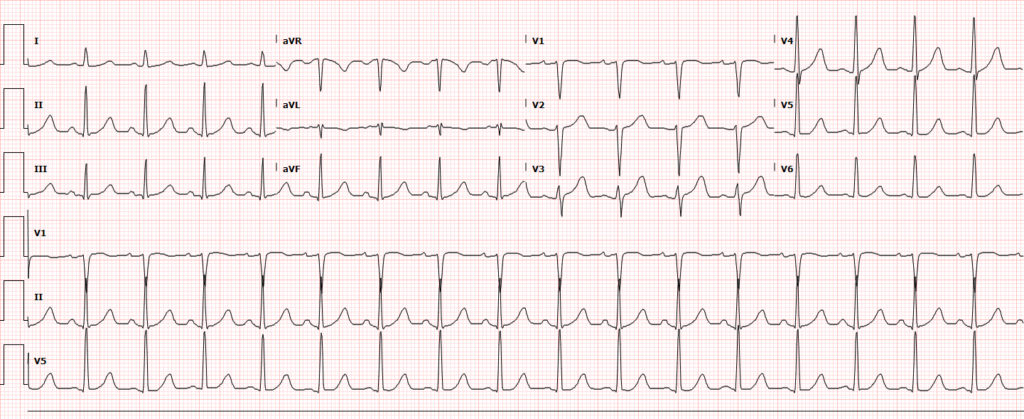

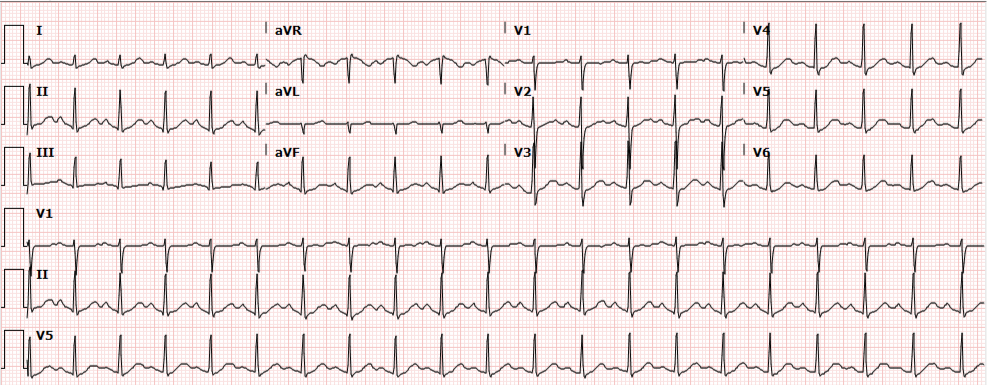

ECG

Impression/Plan

Palpitations due to sinus tachycardia from symptomatic hyperthyroidism secondary to medication non-adherence. Improved with propranolol, discharged with methimazole and PMD follow-up.

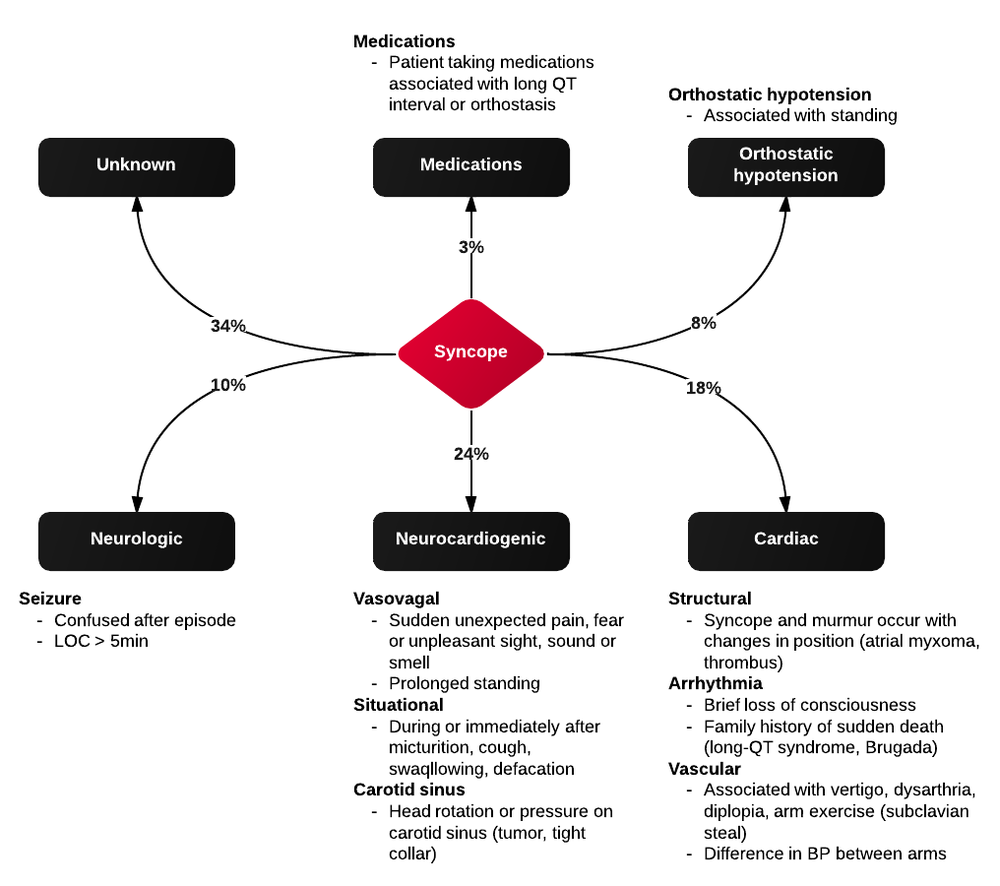

Algorithm for the Evaluation and Management of Palpitations1, 2

Evaluation of Palpitations

History and Physical

- Subjective description of symptom quality

- Rapid and regular beating suggests paroxysmal SVT or VT. Rapid and irregular beating suggests atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, or variable conduction block.

- Stop/start sensation: PAC or PVC

- Rapid fluttering: Sustained supraventricular or ventricular tachycardia

- Pounding in neck: Produced by canon A waves from AV dissociation (VT, complete heart block, SVT)

- Onset and offset

- Random, episodic, lasting instants: Suggests PAC or PVC

- Gradual onset and offset: Sinus tachycardia

- Abrupt onset and offset: SVT or VT

- Syncope

- Suggests hemodynamically significant arrhythmia, often VT

- Examination

- Identify evidence of structural, valvular heart disease

ECG1

| ECG Finding | Presumed etiology |

|---|---|

| Short PR, Delta waves | WPW, AVRT |

| LAA, LVH | Atrial fibrillation |

| PVC, BBB | Idiopathic VT |

| Q-waves | Prior MI, VT |

| QT-prolongation | VT (polymorphic) |

| LVH, septal Q-waves | HCM |

| Blocks |

References

- Zimetbaum P, Josephson ME. Evaluation of patients with palpitations. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(19):1369-1373. doi:10.1056/NEJM199805073381907.

- Probst MA, Mower WR, Kanzaria HK, Hoffman JR, Buch EF, Sun BC. Analysis of emergency department visits for palpitations (from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey). The American Journal of Cardiology. 2014;113(10):1685-1690. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.02.020.

- Abbott AV. Diagnostic approach to palpitations. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71(4):743-750.