Brief HPI:

A 63 year-old female with a history of hypertension, diabetes, and deep venous thrombosis on warfarin presents with epistaxis. She noted the spontaneous onset of nose bleeding 15 minutes prior to presentation. She had attempted compression but symptoms persisted so she was brought to the emergency department. On initial evaluation, she was in no acute distress and vital signs were normal. She was compressing her distal nares and was spitting up blood.

Oxymetolazone was administered and the patient was instructed regarding the appropriate position for compression, however bleeding continued when reassessed at 10- and then 30-minutes of compression. A bleeding focus could not be visualized on rhinoscopy so a nasal tampon was inserted with resolution of bleeding. Bleeding did not recur after two hours of observation in the emergency department. The patient’s INR was therapeutic two days prior to presentation and she was instructed to continue her usual regimen. At primary care follow-up two days later, the compression device was successfully removed.

Algorithm for the Management of Epistaxis1,2

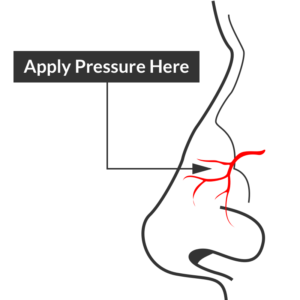

External Compression

Begin with simple measures while preparing the necessary equipment and medications. Request that the patient gently blow their nose to clear clots, administer oxymetolazone 0.05% two sprays into the affected side. Apply firm pressure below the nasal bridge continuously for at least 10 minutes before reassessment. Commercial compression devices are available, or can be fashioned with tongue depressors3. Alternatively, the patient can apply pressure themselves.

Cautery

Again ask the patient to blow their nose to remove clots. Apply topical anesthetic for patient comfort prior to inspection with a nasal speculum. Additional suction (small tip, Frazier) may be required to improve visualization. If the bleeding site is identified, apply silver nitrate circumferentially around the source, then directly over the site. Avoid prolonged exposure or exposure to opposing sides of the nasal septum. If hemorrhage control is successful, patients may be discharged with a topical antimicrobial ointment such as polymixin-bacitracin-neomycin.

Packing 4,5

Multiple commercial anterior packing devices are available. Placement technique is similar for most, generally involving lubrication of the device with antimicrobial ointment or sterile water, sliding the device along the floor of the nasal cavity, followed by injection or inflation of the device to support tamponade. The incorporation of tranexamic acid (500mg in 5mL) into any phase of anterior packing may be beneficial 6,7. Packing the contralateral side to further support tamponade may be required.

Commonly used commercial devices are:

- Merocel: lubricate with antimicrobial ointment, once deployed can rehydrate with saline or topical vasoconstrictor

- Rapid Rhino

- Rhino Rocket

Packing material should remain for 48-72 hours, during which patients should be re-evaluated. Prophylactic systemic antibiotics for the prevention of sinusitis or toxic shock are likely not required8.

Thrombogenic materials such as Floseal or Surgicel can also be used and may be better tolerated than packing materials9.

Posterior Control

If bleeding persists despite the above measures, a posterior site should be considered. Dual-balloon commercial devices are available for the control of posterior epistaxis and are deployed in a similar fashion to anterior devices. Once inserted, the posterior balloon should be inflated with air – with the volume guided by tension of the pilot cuff. The anterior balloon can then be inflated in a similar fashion. The posterior balloon cuff should be reinspected after 5 minutes as additional inflation may be required.

Commonly used commercial devices are:

- Rapid Rhino

- Epistat

- Storz T3100

If a commercial device is unavailable, a Foley catheter may be used. The catheter is introduced into the affected side. Once the tip is visualized in the posterior oropharynx, the balloon is inflated with approximately 10mL of sterile water. The catheter is then withdrawn gently to seat the balloon posteriorly. The catheter is secured in position against the nares with a clamp (taking care to pad the nares with gauze to prevent trauma) 10,11.

Patients with posterior epistaxis should be admitted with otolaryngology consultation. If bleeding continues despite these measures, emergent otolaryngology consultation for operative management is warranted.

Causes of Epistaxis12

References

- Leong SCL, Roe RJ, Karkanevatos A. No frills management of epistaxis. Emerg Med J. 2005;22(7):470-472. doi:10.1136/emj.2004.020602.

- Barnes ML, Spielmann PM, White PS. Epistaxis: a contemporary evidence based approach. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2012;45(5):1005-1017. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2012.06.018.

- Moxham V, Reid C. Controlling epistaxis with an improvised device. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2001;18(6):518. doi:10.1136/emj.18.6.518.

- Singer AJ, Blanda M, Cronin K, et al. Comparison of nasal tampons for the treatment of epistaxis in the emergency department: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45(2):134-139. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.10.002.

- Iqbal IZ, Jones GH, Dawe N, et al. Intranasal packs and haemostatic agents for the management of adult epistaxis: systematic review. J Laryngol Otol. 2017;131(12):1065-1092. doi:10.1017/S0022215117002055.

- MD RZ, MD PM, MD SA, PhD AG, MD MS. A new and rapid method for epistaxis treatment using injectable form of tranexamic acid topically: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2013;31(9):1389-1392. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2013.06.043.

- Kamhieh Y, Fox H. Tranexamic acid in epistaxis: a systematic review. Clin Otolaryngol. 2016;41(6):771-776. doi:10.1111/coa.12645.

- MD BC. Are Prophylactic Antibiotics Necessary for Anterior Nasal Packing in Epistaxis? YMEM. 2015;65(1):109-111. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.08.011.

- Mathiasen RA, Cruz RM. Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial of a Novel Matrix Hemostatic Sealant in Patients with Acute Anterior Epistaxis. The Laryngoscope. 2005;115(5):899-902. doi:10.1097/01.MLG.0000160528.50017.3C.

- Holland NJ, Sandhu GS, Ghufoor K, Frosh A. The Foley catheter in the management of epistaxis. Int J Clin Pract. 2001;55(1):14-15.

- Hartley C, Axon PR. The Foley catheter in epistaxis management–a scientific appraisal. J Laryngol Otol. 1994;108(5):399-402.

- Kucik CJ, Clenney T. Management of epistaxis. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71(2):305-311.