Brief H&P:

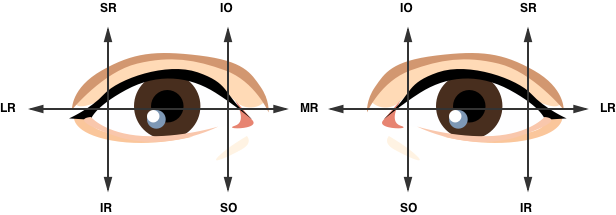

A young male with no past medical history presents to the emergency department after assault. He was punched multiple times in the face and has since noted double vision, worse with upward gaze. Examination revealed right peri-orbital edema with associated limitation to upward gaze.

Imaging:

CT Maxillofacial Non-contrast

Inferior orbital wall fracture with herniation of the inferior rectus muscle.

Extraocular Muscle Actions:

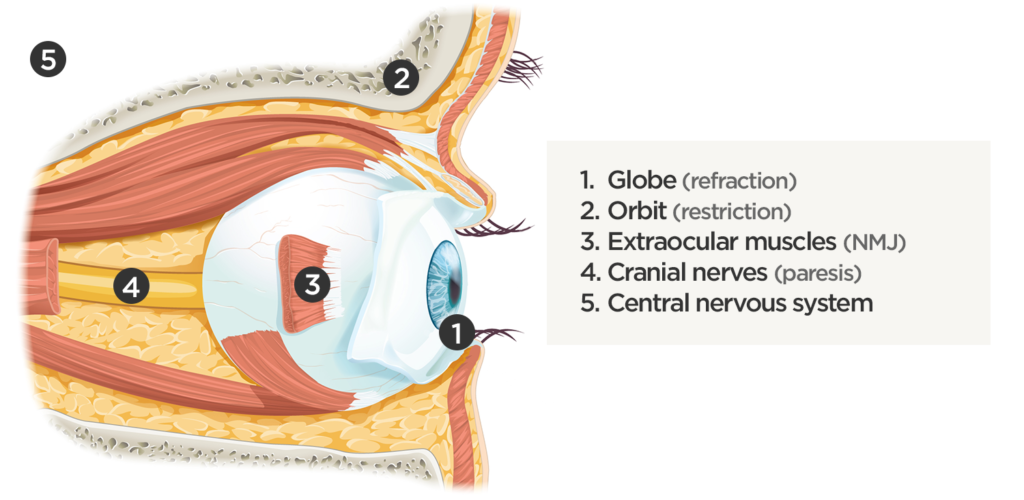

Affected Anatomic Sites in Diplopia:

Coordinated eye positioning is affected by voluntary movements (requiring cranial nerve control for conjugate eye movements), vergence (for depth adjustments), as well as reflexive adjustments for head movement (requiring vestibular input). As with any motor activity, neuromuscular control must be normal with unrestricted movement of the globe within the orbit.

Algorithm for the Evaluation of Diplopia:

Diplopia has been explored previously on ddxof. The earlier algorithm was focused on identifying the paretic nerve. This algorithm uses features of the history and physical examination to identify potential etiologic causes of diplopia.

References:

- Rucker JC, Tomsak RL. Binocular diplopia. A practical approach. Neurologist. 2005;11(2):98-110. doi:10.1097/01.nrl.0000156318.80903.b1.

- Friedman DI. Pearls: diplopia. Semin Neurol. 2010;30(1):54-65. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1244995.

- Alves M, Miranda A, Narciso MR, Mieiro L, Fonseca T. Diplopia: a diagnostic challenge with common and rare etiologies. Am J Case Rep. 2015;16:220-223. doi:10.12659/AJCR.893134.

- Dinkin M. Diagnostic approach to diplopia. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2014;20(4 Neuro-ophthalmology):942-965. doi:10.1212/01.CON.0000453310.52390.58.

- Marx J, Walls R, Hockberger R. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine – Concepts and Clinical Practice. 8 ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013:176-183.

- Nazerian P, Vanni S, Tarocchi C, et al. Causes of diplopia in the emergency department: diagnostic accuracy of clinical assessment and of head computed tomography. Eur J Emerg Med. 2014;21(2):118-124. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0b013e3283636120.

- Low L, Shah W, MacEwen CJ. Double vision. BMJ. 2015;351:h5385. doi:10.1136/bmj.h5385.

- Danchaivijitr C, Kennard C. Diplopia and eye movement disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75 Suppl 4:iv24-iv31. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2004.053413.

- Huff JS, Austin EW. Neuro-Ophthalmology in Emergency Medicine. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2016;34(4):967-986. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2016.06.016.