Brief HPI

A 72 year-old male with a history of hypertension and hiatal hernia presents to the emergency department with one week of generalized weakness. His family report decreased oral intake with frequent emesis over the past four days. He denies chest pain, shortness of breath, abdominal pain, or other complaints. During the interview he has a generalized tonic-clonic seizure which persists for five minutes despite the administration of 4mg of lorazepam.

An Algorithm for the Management of Seizures

The management of active seizures is algorithmic, starting with a rapid assessment of airway patency, supporting ventilation (with appropriate positioning, nasopharyngeal airway adjuncts and bag-valve mask if needed) and ensuring adequate perfusion. Patients should have continuous vital sign monitoring, supplemental oxygen to maintain oxygen saturation >92% and intravenous access1.

Pharmacologic treatment follows a stepwise approach, detailed in the algorithm below. The focus is on immediate stabilization and progressively escalating anti-epileptic drugs eventually requiring endotracheal intubation and continuous infusions of sedatives2-4.

Pathophysiology

Seizures are caused by excessive and disorganized neuronal activation, typically induced by global alterations in the production and transmission of impulses (electrolyte derangements, drugs/toxins, infection), or foci of increased irritability (hemorrhage, stroke, mass) – a pathophysiologic motif that mimics cardiac tachyarrhythmias (sympathomimetic toxicity or scarred myocardium for example)1. Status epilepticus, defined as a seizure lasting greater than five minutes or recurrent seizures without a return to normal baseline, shares an equally high short-term mortality – greater than 20%5.

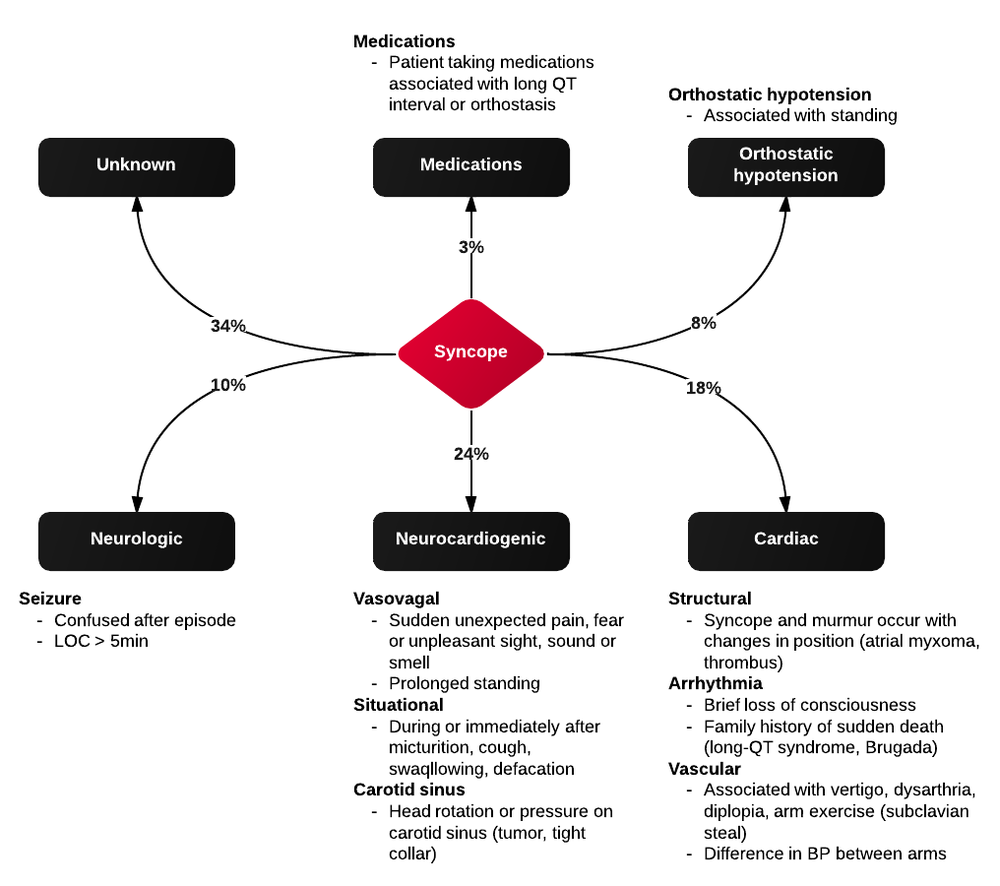

Syncope vs. Seizure

The algorithm below details historical and examination features that may assist with distinguishing epileptic seizure from non-epileptic activity6,7.

Case Conclusion

The patient continued to seize and a point-of-care chemistry panel revealed a serum sodium of 108mEq/L. Seizures abate after the infusion of hypertonic saline (100mL of 3% saline over 10 minutes, repeated until cessation of seizures). While hyponatremia is generally corrected slowly – owing to the risk of osmotic demyelination – immediate correction in this setting is critical8.

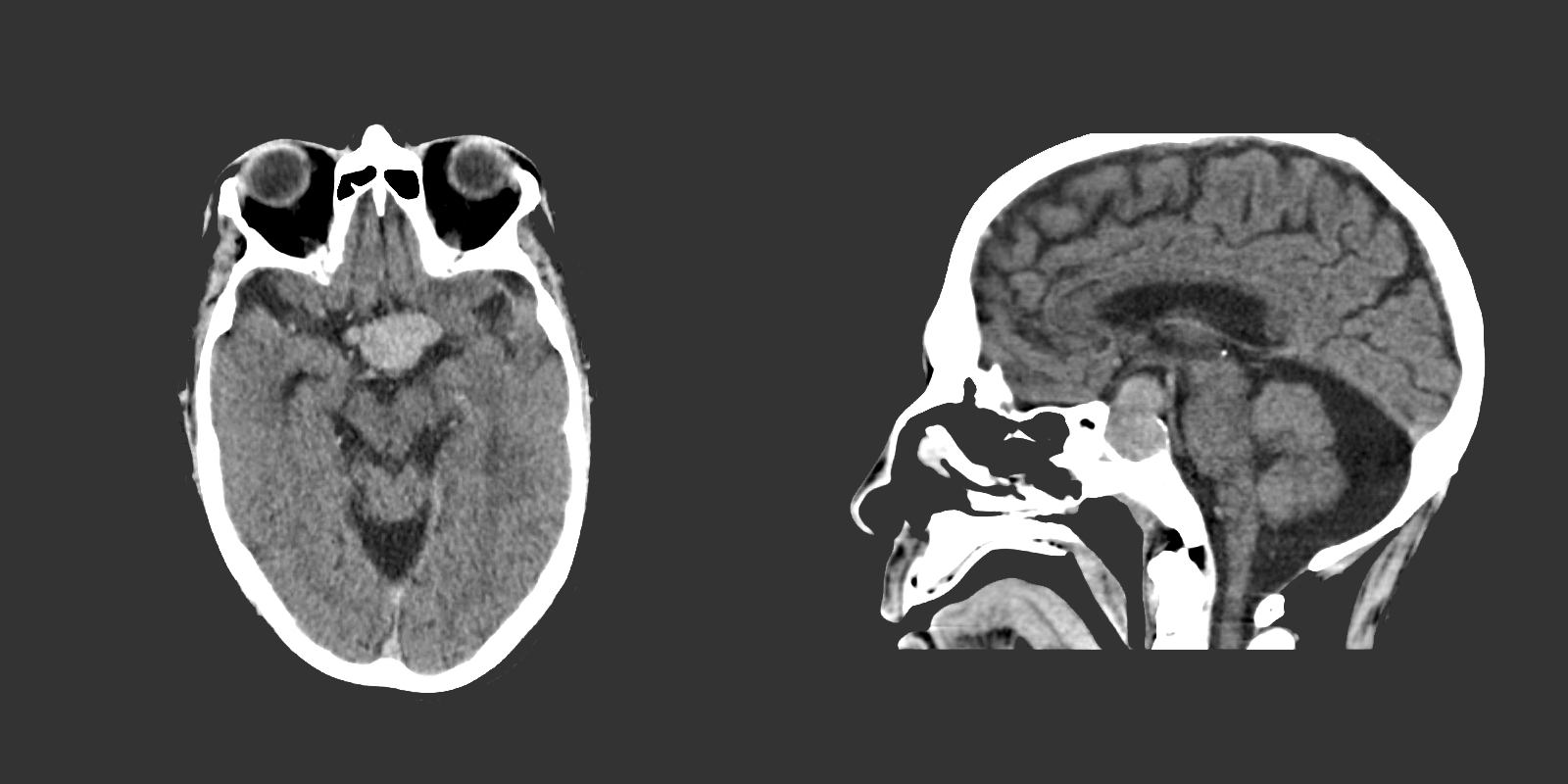

The remainder of the patient’s evaluation demonstrated urine osmolarity is 389mOsm/kg and urine sodium is 53mmol/L, in the setting of relative euvolemia on examination these findings were consistent with SIADH. Head computed tomography is obtained and reveals a sellar mass.

References

- McMullan JT, Davitt AM, Pollack CV Jr. Seizures. In: Rosen’s Emergency Medicine. Mosby Incorporated; 2002:2808. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70350-7.

- Billington M, Kandalaft OR, Aisiku IP. Adult Status Epilepticus: A Review of the Prehospital and Emergency Department Management. J Clin Med. 2016;5(9):74. doi:10.3390/jcm5090074.

- Huff JS, Morris DL, Kothari RU, Gibbs MA, Emergency Medicine Seizure Study Group. Emergency department management of patients with seizures: a multicenter study. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2001;8(6):622-628.

- Prasad M, Krishnan PR, Sequeira R, Al-Roomi K. Anticonvulsant therapy for status epilepticus. Prasad M, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;16(9):CD003723. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003723.pub3.

- Logroscino G, Hesdorffer DC, Cascino G, Annegers JF, Hauser WA. Short-term mortality after a first episode of status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 1997;38(12):1344-1349.

- Sheldon R, Rose S, Ritchie D, et al. Historical criteria that distinguish syncope from seizures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(1):142-148.

- McKeon A, Vaughan C, Delanty N. Seizure versus syncope. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(2):171-180. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70350-7.

- Goh KP. Management of hyponatremia. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69(10):2387-2394.