Brief H&P

A 68 year-old male with hypertension and gout presents with rash for 2-3 weeks. He note some subjective fevers but is otherwise asymptomatic. He denies recent travel or sick contacts. When asked about his medications, he reports that his primary care provider started him on allopurinol approximately two months ago.

He first noted the rash on his face, characterizing it as “pimples” which were slightly pruritic. The lesions subsequently spread to his trunk and extremities and have been growing in size.

Objectively, vital signs were notable for fever (38.2°C) and tachycardia (108bpm). Examination demonstrated diffuse blanching erythema most prominent on the trunk and extremities. The remainder of the physical examination was normal. Laboratory studies were obtained and notable for a complete blood count (CBC) with peripheral eosinophilia, as well as mildly elevated serum transaminases.

The patient was diagnosed with Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS), likely owing to the initiation of a xanthine oxidase inhibitor. He improved after withdrawal of the drug and a brief course of systemic corticosteroids.

Principles of Dermatologic Emergencies

Critical dermatologic processes can be broadly divided into two categories:

1. Cutaneous manifestation of critical illness

The presence of a dermatologic abnormality does not itself represent a life-threat. Instead, the skin lesion is a signal suggestive of the presence of an underlying critical process. The prototypical example would be the petechiae/purpura in meningococcemia.

2. Acute Skin Failure

As with any other organ system failure, Acute Skin Failure carries significant morbidity and mortality and is characterized by derangements in normal skin function.

- Critical functions of skin

- Temperature regulation

- Protection against excess fluid loss

- Mechanical barrier to prevent penetration of foreign materials

- Important pathophysiologic changes in ASF

- Increased peripheral vasodilation (dramatic increase in cardiac output to low-resistance circuits) and increased vascular permeability resulting in relative hypovolemia and shock.

- Increased blood flow and dysfunction of eccrine sweat glands results in altered temperature regulation (usually hypothermia)

- Fluid imbalances occur, similar to burns (transepidermal water loss) which varies in quality somewhat between “dry” (erythroderma) and “wet” (vesiculobullous) diseases

- Electrolytes: increased basal metabolic rate, hyperglycemia (insulin resistance), hypophosphatemia, protein depletion

- Barrier dysfunction: increased risk of infection

- Management

- Intensive Care Unit: Dermatologic (DICU) or Burn Center preferred

- Treatment: Temperature management, early enteral nutrition, fluid/electrolyte management, local wound care, disease-specific management

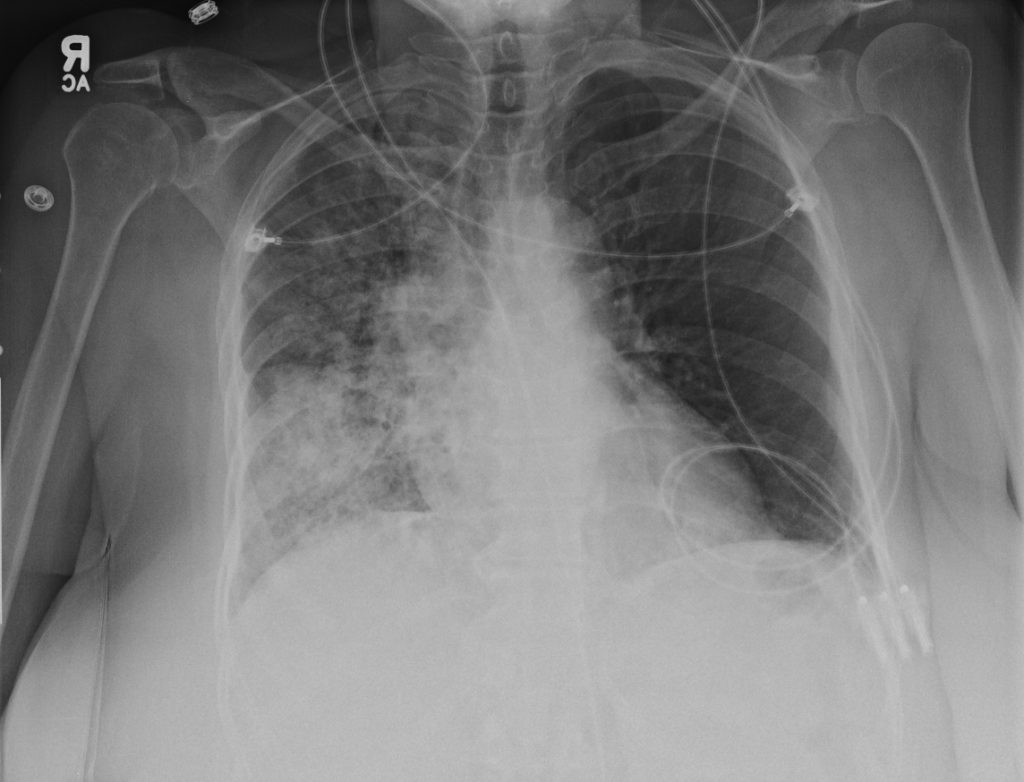

- Complications: Sepsis/shock, ARDS, high-output CHF, known complications of critical illness (multi-organ failure, GI ulcers, VTE)

- Long-term complications: occular (ectropion, keratitis, ulcer), esophageal (stricture), GU (urethral stricture, phimosis, vaginal stenosis), Integumentary (scarring, alopecia)

Skin Lesions and their Pathophysiology

The objective of this algorithm is to develop a systematic approach to the evaluation of dermatologic processes with a focus on the identification of dermatologic emergencies. The foundation of this approach is an understanding of the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms for each of four broad categories of dermatologic processes which guide the resultant differential diagnosis.

Erythroderma

- Pathophysiology

- Extensive cutaneous capillary dilation, results in widespread exfoliation of the epidermis

- Inflammatory mediators result in dramatic increase of epidermal turnover rate, accelerated mitotic rate, increased number of germinative skin cells.

- Causes

- Exfoliative toxin

- Eosinophils

- Basophils/Histamine

- Skin-homing T-cells

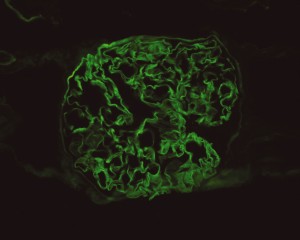

Petechiae/Purpura

- Pathophysiology

- Represent the passage of erythrocytes from the intravascular to extravascular compartment

- May be the result of disruption of vascular integrity (trauma, infection, vasculitis) or disorders of primary or secondary hemostasis

- Palpable

- If lesions are palpable, this may suggest a more prominent underlying inflammatory process such as vasculiitis.

- When cutaneous manifestations are identified, other small vessels may be affected (commonly renal and pulmonary

Fluid-filled

- Pustule

- Pustules more commonly suggest an infectious process (bacterial, fungal)

- Vesiculobullous

- Vesiculobullous lesions are generally more concerning

- Loss of basic structural elements maintaining cohesion between keratinocytes in the epidermis, or between the epidermal layer and the dermis (near basement membrane zone).

- Intraepidermal blisters tend to be flaccid, fragile and thin-roofed.

- Subepidermal blisters have a thick roof and can remain intact when compressed

- Often due to autoantibodies targeting structural proteins in the skin.

Maculopapular

- Pathophysiology

- Catch-all term with a wide range of potential pathophysiologic mechanisms and causative etiologies.

- Any process that results in erythroderma, petechiae, or fluid-filled lesions may start as a macule or papule.

- Pathophysiology is of little guidance in this category where we must instead rely on the patient’s history and identification of red-flags to exclude dermatologic emergencies.

- High-risk Features (Identified by dermatologists to stratify urgency of inpatient consultations):

- Ill-appearing, vital sign instability

- New-onset fever with rash

- Mucocutaneous or ocular lesions

- Recent introduction of anti-convulsant or sulfa-drug

- Skin pain

- Immunocompromised

Algorithm for the Evaluation of Dermatologic Processes

An algorithm for the evaluation of dermatologic processes was developed initially by Lynch in 1984. Since then, several modified Lynch algorithms have emerged. The concept of an algorithmic approach to dermatologic diagnosis was further expanded with the development of VisualDx, a decision-support application. There is evidence to suggest that the use of algorithms and decision support tools like VisualDx (and by extension this algorithm) may aid with the development of more thorough differential diagnoses and improve diagnostic accuracy.

References

Reviews

- Wolf R, Parish LC, Parish JL. Emergency Dermatology, Second Edition. August 2017:1-369.

- Usatine RP, Sandy N. Dermatologic emergencies. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(7):773-780.

- Shilpi Khetarpal MD, Anthony Fernandez MP. Dermatological Emergencies. Cleveland Clinic. http://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/dermatology/dermatological-emergencies/. Published August 2014. Accessed August 5, 2017.

- McQueen A, Martin SA, Lio PA. Derm emergencies: detecting early signs of trouble. J Fam Pract. 2012;61(2):71-78.

- Browne BJ, Edwards B, Rogers RL. Dermatologic emergencies. Prim Care. 2006;33(3):685–95–vi. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2006.06.002.

- Drage LA. Life-threatening rashes: dermatologic signs of four infectious diseases. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 1999;74(1):68-72. doi:10.4065/74.1.68.

- Baibergenova A, Shear NH. Skin conditions that bring patients to emergency departments. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(1):118-120. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.246.

Erythroderma

- Tan TL, Chung WM. A case series of dermatological emergencies – Erythroderma. Med J Malaysia. 2017;72(2):141-143.

- Karakayli G, Beckham G, Orengo I, Rosen T. Exfoliative dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59(3):625-630.

Petechiae/Purpura

- Stevens GL, Adelman HM, Wallach PM. Palpable purpura: an algorithmic approach. Am Fam Physician. 1995;52(5):1355-1362.

Algorithms

- Lynch PJ, Edminster SC. Dermatology for the nondermatologist: a problem-oriented system. YMEM. 1984;13(8):603-606.

- Nguyen T, Freedman J. Dermatologic Emergencies: Diagnosing And Managing Life-Threatening Rashes. Emergency Medicine Practice. 2002;4(9):1-28.

- Murphy-Lavoie H, LeGros TL. Emergent Diagnosis of the Unknown Rash: an Algorithmic Approach-Rash Is Among the Top 20 Reasons for ED Visits in the United States. Certain Rashes …. Emergency Medicine; 2010.

- Dean S. Emergency Medicine Dermatology. 2017:1-20. doi:10.21980/J8DW21.

- Talley NJ, O’Connor S. Clinical Examination. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013.

- Jack AR, Spence AA, Nichols BJ, Peng DH. A simple algorithm for evaluating dermatologic disease in critically ill patients: a study based on retrospective review of medical intensive care unit consults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61(4):728-730. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.12.025.

DRESS

- McQueen A, Martin SA, Lio PA. Derm emergencies: detecting early signs of trouble. J Fam Pract. 2012;61(2):71-78.

- Cardoso CS, Vieira AM, Oliveira AP. DRESS syndrome: a case report and literature review. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011. doi:10.1136/bcr.02.2011.3898.

Evidence-Based Algorithms

- David CV, Chira S, Eells SJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy in patients admitted to hospitals with cellulitis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17(3):1.

- Chou W-Y, Tien P-T, Lin F-Y, Chiu P-C. Application of visually based, computerised diagnostic decision support system in dermatological medical education: a pilot study. Postgrad Med J. 2017;93(1099):256-259. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2016-134328.