Brief HPI:

Intraocular foreign body

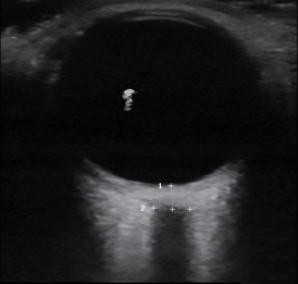

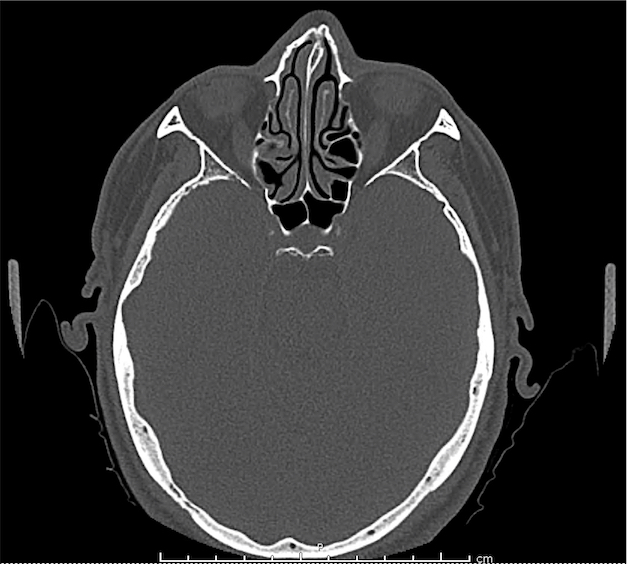

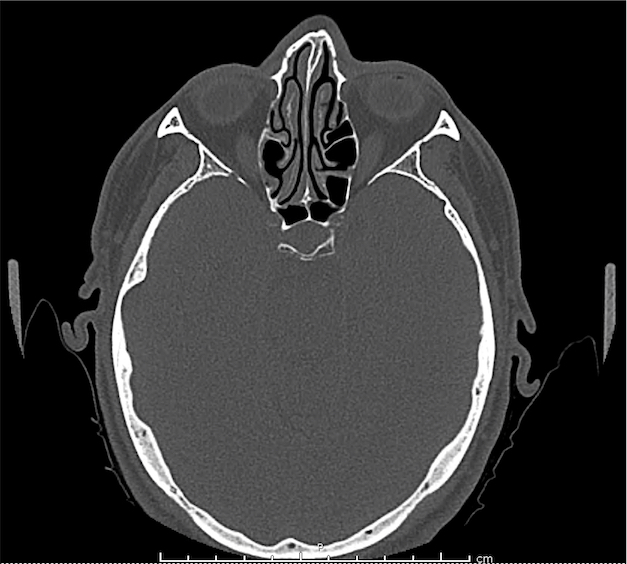

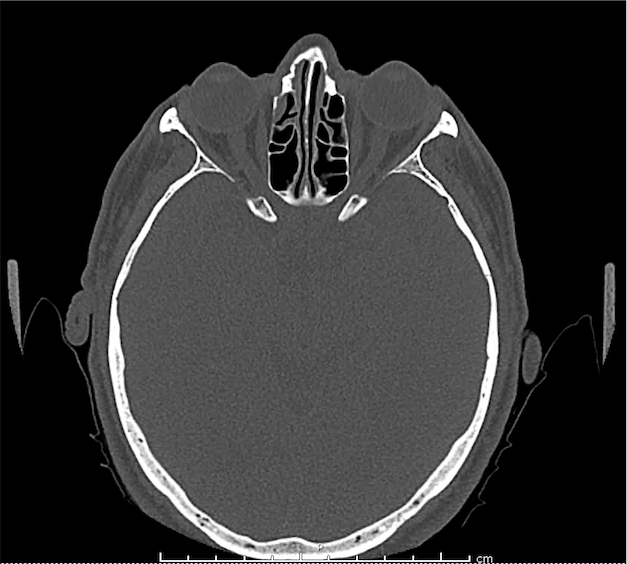

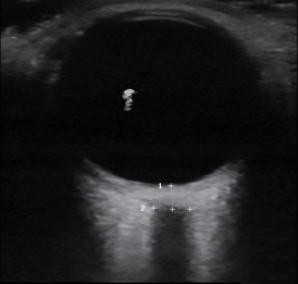

A middle-aged male with no past medical history presents with blurred vision. He reported that he was hammering while at work approximately 3 days prior to presentation and felt something enter his left eye. He denies eye pain, has noted some eye redness and increased tearing. Denies prior eye surgery or procedures. Physical examination demonstrates normal visual acuity, minimal left nasal conjunctival injection sparing the limbus, and an irregular left pupil that is minimally reactive. A no-pressure ocular ultrasound was performed and demonstrated a hyperechoic structure in the globe suggestive of foreign body which was confirmed on computed tomography of the orbit. The patient was taken to the operating room for removal.

Imaging

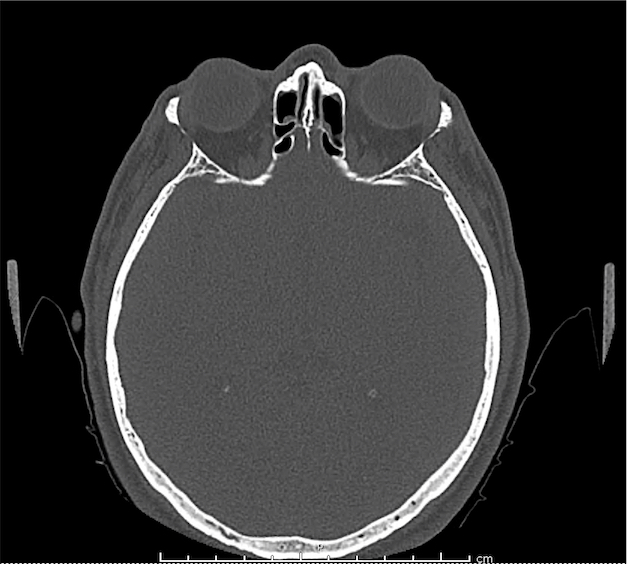

CT Orbit without contrast

Punctate density within the left globe compatible with foreign body.

Algorithm for the Evaluation of Visual Complaints with Ocular Ultrasonography

Gallery

The POCUS Atlas The ultrasound images and videos used in this post come from

The POCUS Atlas, a collaborative collection focusing on rare, exotic and perfectly captured ultrasound images.

Orbital Abscess

Lens dislocation

Retinal detachment

Vitreous hemorrhage

Posterior vitreous detachment

ONSD (increased)

Central retinal artery flow (normal)

Central retinal artery occlusion

Applications1,2

Useful for the evaluation of intraocular processes:

- Retinal detachment

- Vitreous hemorrhage/detachment

- Intraocular foreign body

- Lens dislocation

- Retroorbital hemorrhage/abscess

- Retinal vascular processes (CRAO)

Augmentation of physical examination when limited due to facial swelling or trauma:

- Pupil size and reactivity

- Extraocular movements

ONSD

- Normal <5mm adults (>15yo)

- Normal <4.5mm children (1-15yo)

- Normal <4mm infants (<1yo)

- By convention, measurements of the optic nerve sheath diameter are made 3-mm posterior to the globe

Technique

- Apply Tegaderm, ensuring no air bubbles trapped

- Apply copious ultrasound gel

- Use no-pressure technique, anchoring hand against the patient’s forehead, nasal bridge or maxilla

- Probe indicator to the patient’s right for transverse views

- Probe indicator to the patient’s head for longitudinal views

- Start with medium gain then increase to identify subtle findings

Test Characteristics

Prospective observational study evaluating patients presenting with ocular trauma or acute vision complaints underwent ocular ultrasound. Ultrasound findings agreed with the confirmatory test: ophthalmology consultation or advanced imaging (usually computed tomography) in 60 of 61 cases3.

Specific Findings 4,5

Retinal Detachment6-9

Appears as a highly reflective membrane floating in the substance of the vitreous body, moves within vitreous body with eye movement. Remains anchored at the optic nerve and ora serrata.

Posterior Vitreous Detachment10

Both retinal detachments and posterior vitreous detachments show a linear hyperechoic line in the posterior chamber. However, posterior vitreous detachments are not tethered to the optic nerve and will appear to cross midline.

Vitreous Hemorrhage

Seen more easily with high-gain, enhanced by eye movements which demonstrate hyperechoic particles swirling around in the vitreous body.

Retrobulbar Hematoma

Identified by the presence of a hypoechoic structure posterior to the globe. Should prompt a measurement of intra-ocular pressure if simultaneous globe rupture is not suspected.

Lens Dislocation

Usually secondary to blunt trauma, lens displaced from normal position and appears as an echogenic ovoid structure floating freely in the vitreous or over the retina.

Globe Rupture

If the diagnosis of globe rupture is obvious, ultrasound should be avoided. However, the “no-pressure” technique described above likely does not significantly impact intra-ocular pressure and should be safe11,12. Globe rupture can be identified by scleral buckling, anterior chamber collapse, or globe collapse/irregularities.

Optic Nerve Evaluation13-18

Though not a direct assessment of ocular pathology, evaluation of the optic nerve sheath diameter (ONSD) serves as a reliable surrogate for elevated intracranial pressure – emulating fundoscopy for papilledema. See normal measurements and image acquisition above.

Intraocular Foreign Body

The preferred imaging modality for evaluation of intraocular foreign body is orbital computed tomography. Ultrasonographically, foreign bodies are typically hyperechoic.

Central Retinal Artery Occlusion19,20

A more advanced technique, the addition of color Doppler over the central retinal artery may reveal decreased systolic amplitude and diastolic flow in embolic or thrombotic occlusion.

All illustrations are available for free, licensed (along with all content on this site) under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Public License.

Downloads Page License

References

- Kimberly HH, Stone MB. Chapter E5 – Emergency Ultrasound. Ninth Edition. Elsevier Inc.; 2018:e49-e66. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-35479-0.00204-X.

- Knoop KJ, Dennis WR. Ophthalmologic, Otolaryngologic, and Dental Procedures. Seventh Edition. Elsevier Inc.; 2019:1295–1337.e2. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-35478-3.00062-2.

- Blaivas M, Theodoro D, Sierzenski PR. A study of bedside ocular ultrasonography in the emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2002;9(8):791-799.

- Roque PJ, Hatch N, Barr L, Wu TS. Bedside ocular ultrasound. Crit Care Clin. 2014;30(2):227–41–v. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2013.10.007.

- Kilker BA, Holst JM, Hoffmann B. Bedside ocular ultrasound in the emergency department. European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2014;21(4):246-253. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000070.

- Yoonessi R, Hussain A, Jang TB. Bedside ocular ultrasound for the detection of retinal detachment in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(9):913-917. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00809.x.

- Shinar Z, Chan L, Orlinsky M. Use of ocular ultrasound for the evaluation of retinal detachment. J Emerg Med. 2011;40(1):53-57. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.06.001.

- Chu HC, Chan MY, Chau CWJ, Wong CP, Chan HH, Wong TW. The use of ocular ultrasound for the diagnosis of retinal detachment in a local accident and emergency department. Hong Kong Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2017;24(6):263-267. doi:10.1177/1024907917735085.

- Vrablik ME, Snead GR, Minnigan HJ, Kirschner JM, Emmett TW, Seupaul RA. The diagnostic accuracy of bedside ocular ultrasonography for the diagnosis of retinal detachment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(2):199–203.e1. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.02.020.

- Schott ML, Pierog JE, Williams SR. Pitfalls in the Use of Ocular Ultrasound for Evaluation of Acute Vision Loss. J Emerg Med. 2013;44(6):1136-1139. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.11.079.

- Chandra A, Mastrovitch T, Ladner H, Ting V, Radeos MS, Samudre S. The utility of bedside ultrasound in the detection of a ruptured globe in a porcine model. West J Emerg Med. 2009;10(4):263-266.

- Berg C, Doniger SJ, Zaia B, Williams SR. Change in intraocular pressure during point-of-care ultrasound. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(2):263-268. doi:10.5811/westjem.2015.1.24150.

- Tsung JW, Blaivas M, Cooper A, Levick NR. A rapid noninvasive method of detecting elevated intracranial pressure using bedside ocular ultrasound: application to 3 cases of head trauma in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005;21(2):94-98.

- Kimberly HH, Shah S, Marill K, Noble V. Correlation of optic nerve sheath diameter with direct measurement of intracranial pressure. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(2):201-204. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2007.00031.x.

- Blaivas M, Theodoro D, Sierzenski PR. Elevated intracranial pressure detected by bedside emergency ultrasonography of the optic nerve sheath. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2003;10(4):376-381.

- Moretti R, Pizzi B. Optic Nerve Ultrasound for Detection of Intracranial Hypertension in Intracranial Hemorrhage Patients. Journal of Neurosurgical Anesthesiology. 2009;21(1):16-20. doi:10.1097/ANA.0b013e318185996a.

- Rajajee V, Vanaman M, Fletcher JJ, Jacobs TL. Optic Nerve Ultrasound for the Detection of Raised Intracranial Pressure. Neurocrit Care. 2011;15(3):506-515. doi:10.1007/s12028-011-9606-8.

- Major R, al-Salim W. Towards evidence based emergency medicine: best BETs from the Manchester Royal Infirmary. BET 3. Ultrasound of optic nerve sheath to evaluate intracranial pressure. Emerg Med J. 2008;25(11):766-767. doi:10.1136/emj.2008.066845.

- Riccardi A, Siniscalchi C, Lerza R. Embolic Central Retinal Artery Occlusion Detected with Point-of-care Ultrasonography in the Emergency Department. J Emerg Med. 2016;50(4):e183-e185. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.12.022.

- Catalin J Dragos, Jianu S Nina, Munteanu M, Vlad D, Rosca C, Petrica L. Color Doppler imaging features in patients presenting central retinal artery occlusion with and without giant cell arteritis. VSP. 2016;73(4):397-401. doi:10.2298/VSP140814087C.