Brief H&P:

A 43-year-old female with a history of hypertension, diabetes and obesity presents with right-upper quadrant abdominal pain for the past 1 week. The pain is characterized as burning, non-radiating, intermittent (with episodes lasting 10-30 minutes), resolving spontaneously and without apparent provoking features. She notes nausea but no vomiting, no changes in bowel or urinary habits. She similarly denies fevers, chest pain or shortness of breath. Vital signs were normal, and physical examination was notable only for right upper quadrant tenderness to palpation without rigidity or guarding.

An ECG demonstrates normal sinus rhythm, laboratory tests including liver function tests and lipase were normal and a bedside ultrasound of the right upper quadrant was performed demonstrating gallstones and a positive sonographic Murphy sign. The patient was diagnosed with acute cholecystitis, antibiotics were initiated, the patient was maintained NPO while general surgery was consulted.

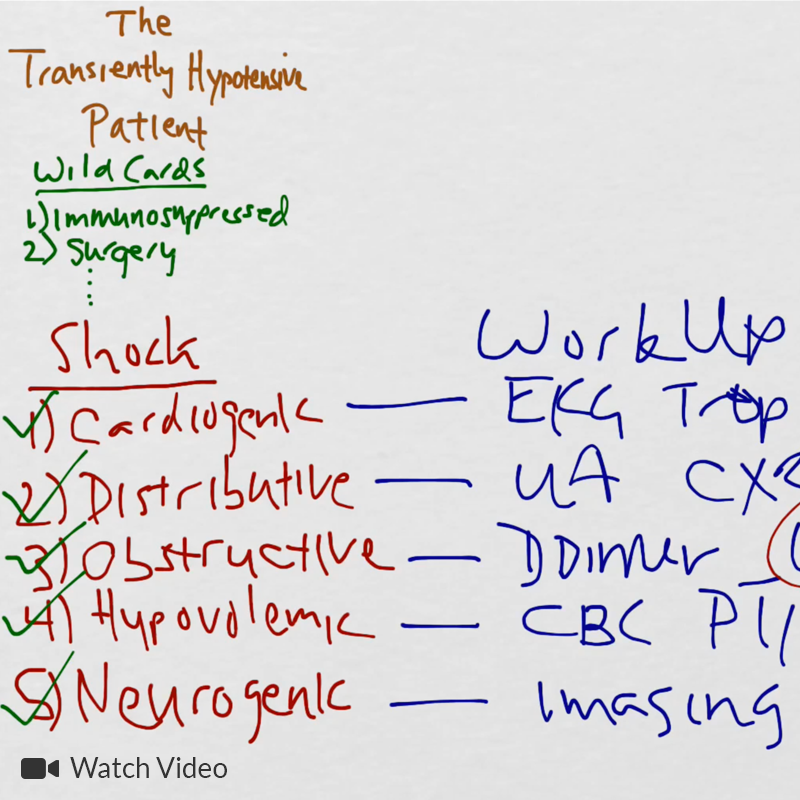

Evaluation of Right-Upper Quadrant Abdominal Pain

The initial evaluation of a patient presenting with right-upper quadrant (or adjacent) abdominal pain typically includes laboratory tests such as a complete blood count, chemistry panel, liver function tests and serum lipase. In patients at risk for atypical presentations for an acute coronary syndrome or with other concerning symptoms, electrocardiography and cardiac enzymes may be indicated.

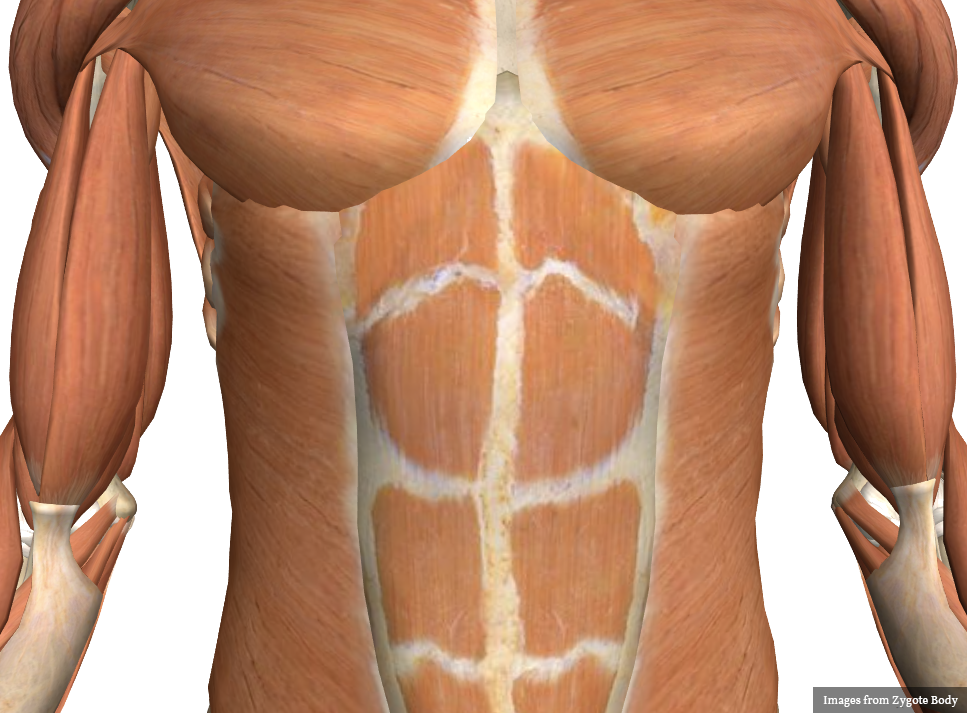

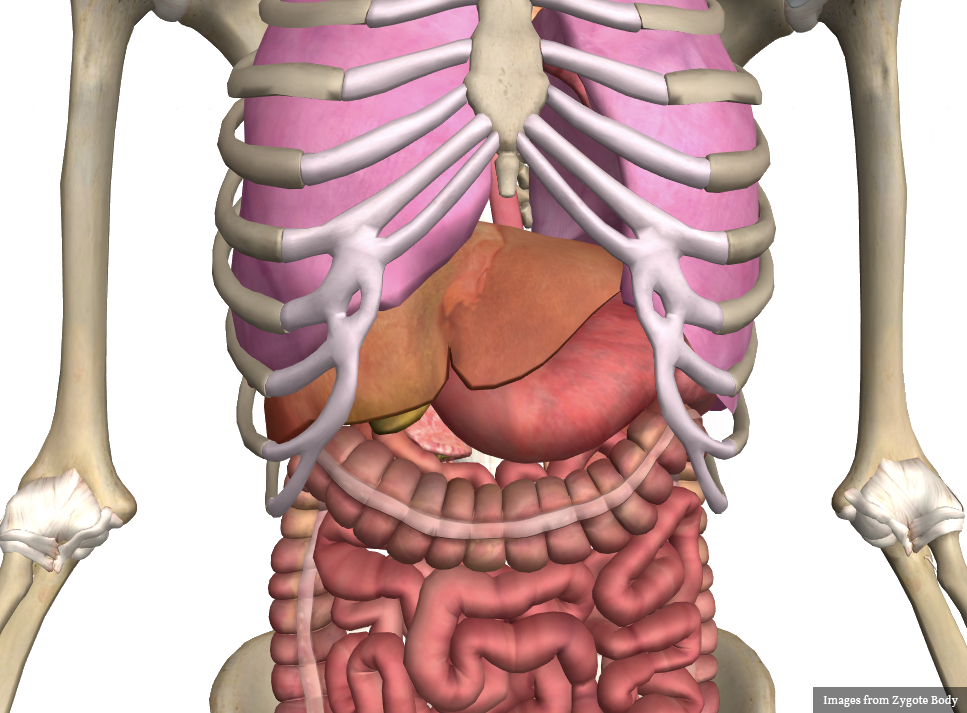

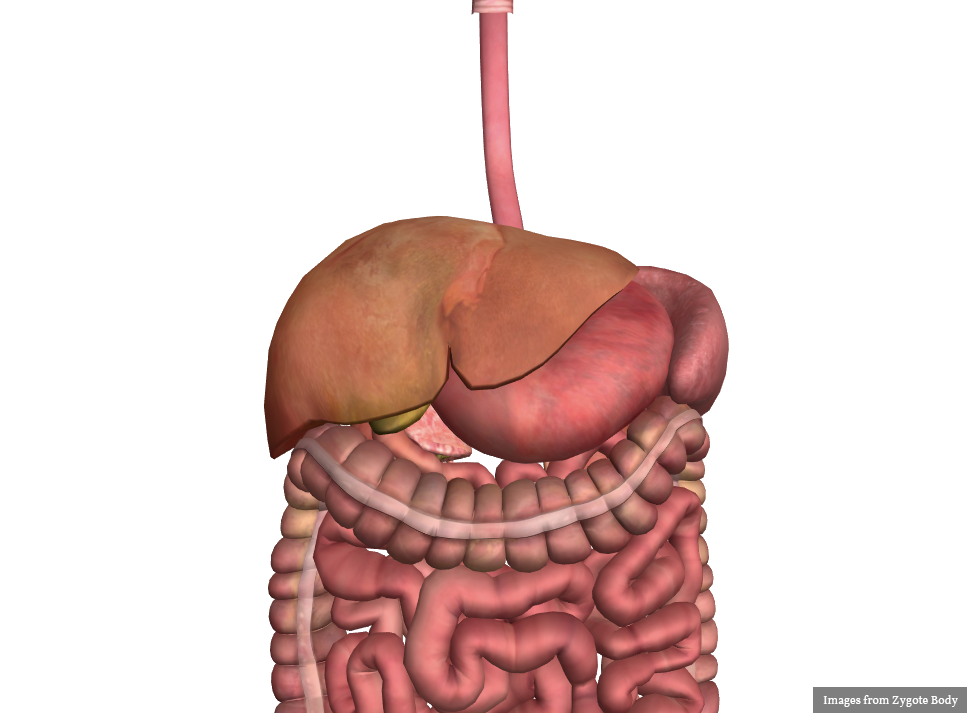

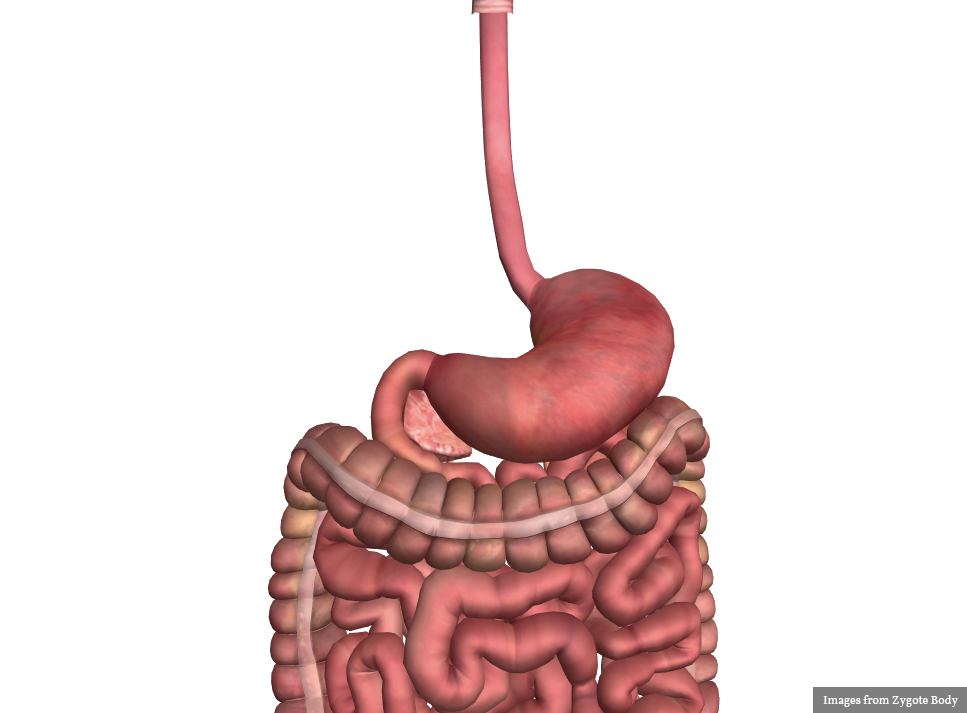

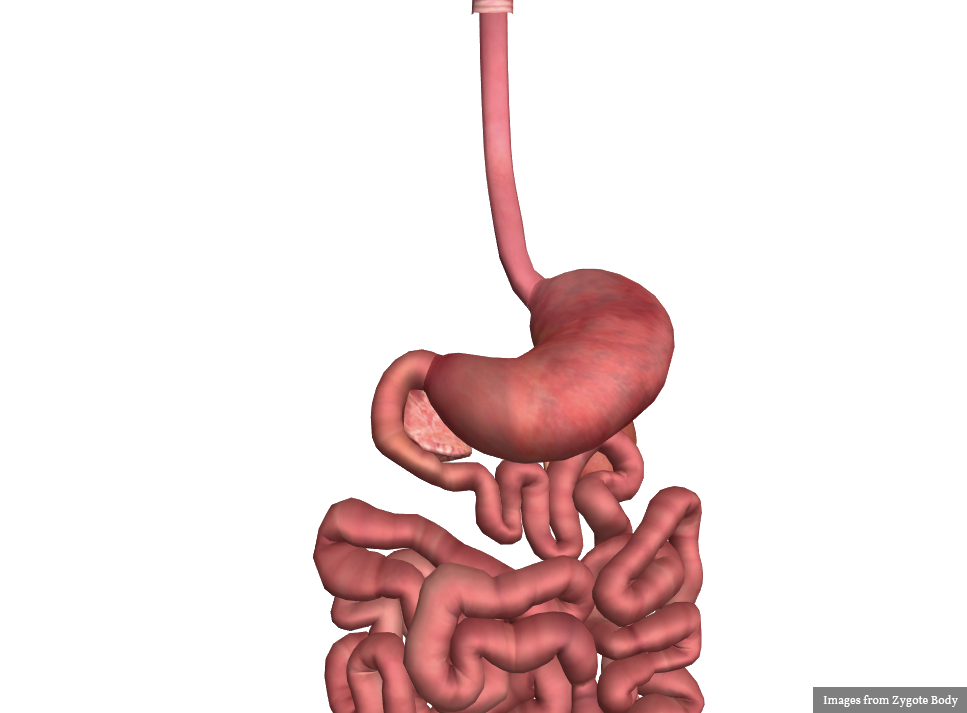

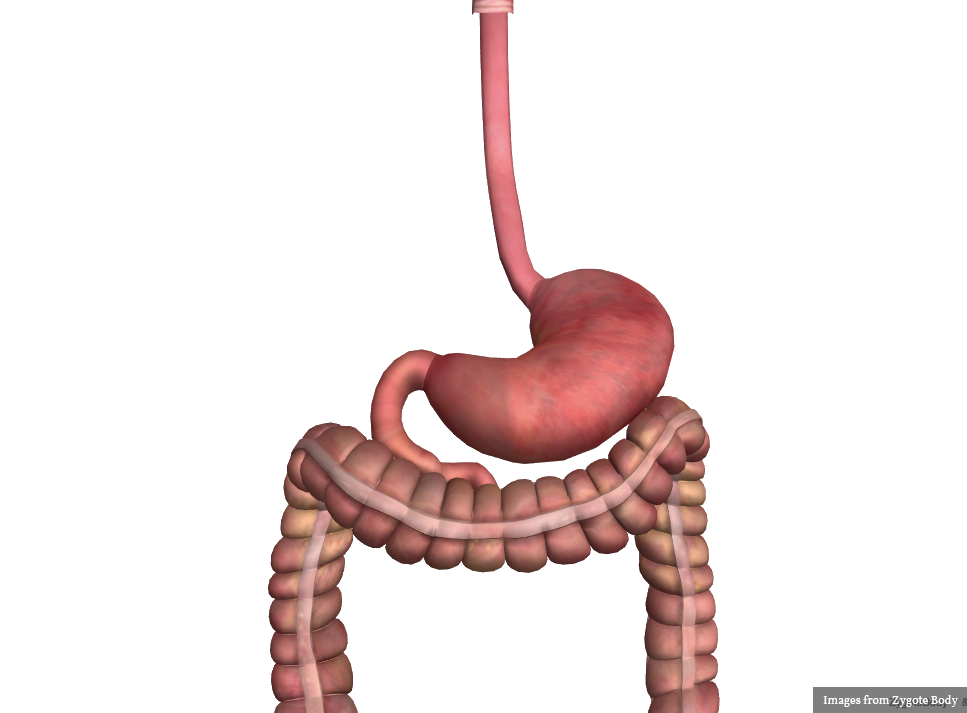

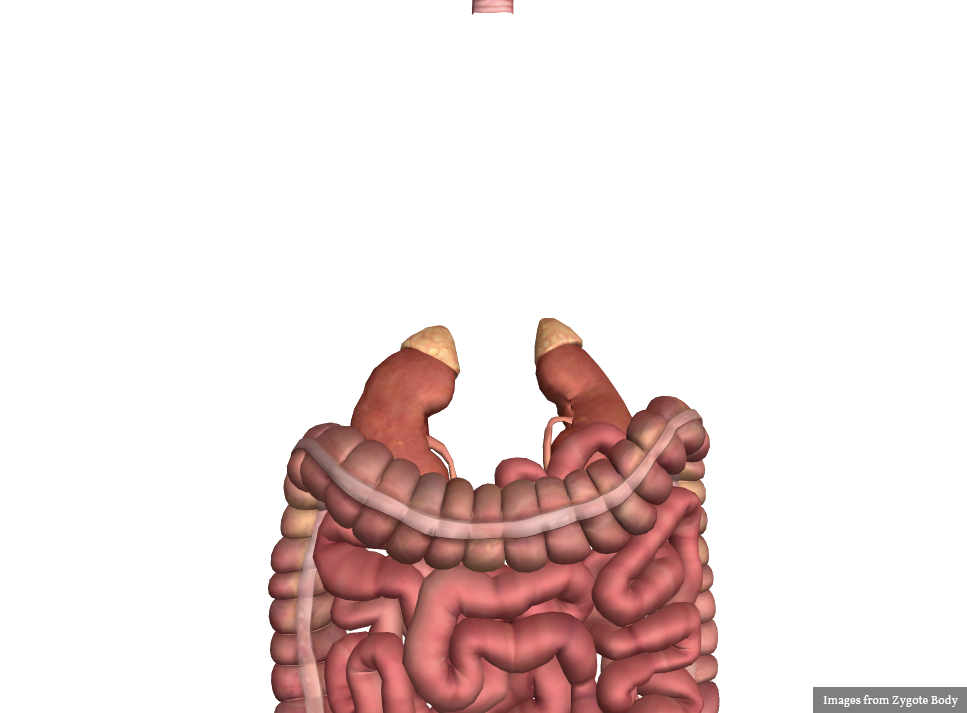

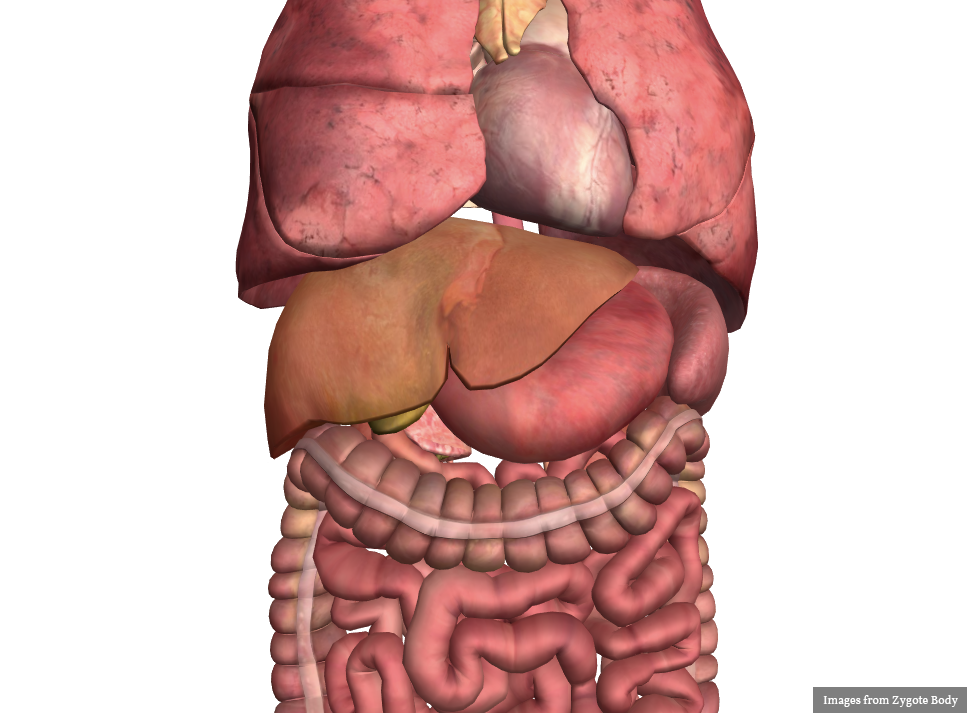

The differential diagnosis is broad. A systematic approach proceeds anatomically from superficial to deeper structures centered around the site of maximal pain.

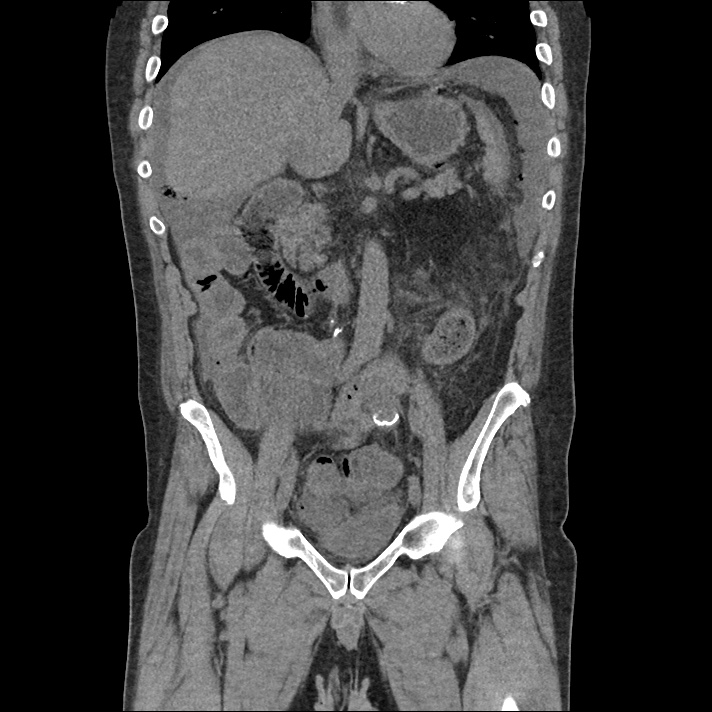

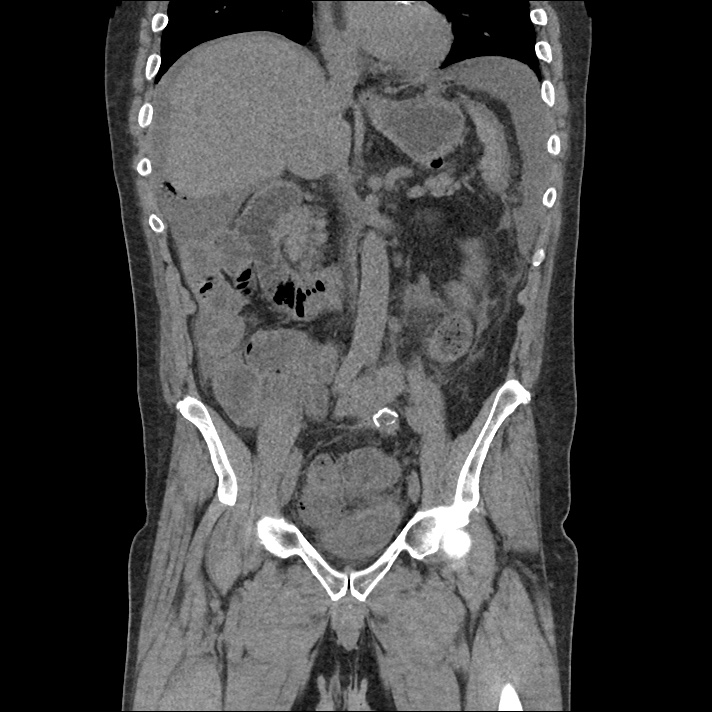

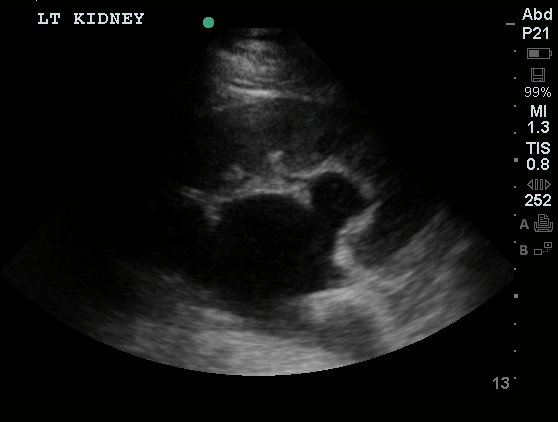

Ultrasound in the Evaluation of Right Upper Quadrant Abdominal Pain

The diagnosis is unlikely to be made based on laboratory tests alone 1. However, the addition of bedside ultrasound, particularly for the evaluation of gallbladder pathology, is both rapid and reliable 2-8. The algorithm below provides a pathway for the incorporation of bedside ultrasound of the right upper quadrant in the evaluation of suspected gallbladder disease.

A normal-appearing gallbladder absent gallstones should prompt a traversal of the anatomic approach to the differential diagnosis detailed above. If gallstones are identified, the association with a positive sonographic Murphy sign is highly predictive of acute cholecystitis 2,5,6,9. Acute cholecystitis may be associated with inflammatory gallbladder changes such as wall-thickening (>3mm) or pericholecystic fluid 3,5,6,10-13. However, in the absence of cholelithiasis or a positive sonographic Murphy sign, these features are non-specific and may be the result of generalized edematous states such as congestive heart failure, renal failure, or hepatic failure and critically-ill patients may develop acalculous cholecystitis 7,11,14. Finally, common bile duct dilation may be due to intra-luminal obstruction as in choledocholithiasis, luminal abnormalities such as strictures, or extra-luminal compression from masses or malignancy. Dilation is generally described as a diameter >6mm – allowing an additional 1mm for every decade over 60 years-old as well as more vague accommodations for patients with prior cholecystectomy 3,5,7,15.

Gallery

The POCUS Atlas The ultrasound images and videos used in this post come from

The POCUS Atlas, a collaborative collection focusing on rare, exotic and perfectly captured ultrasound images.

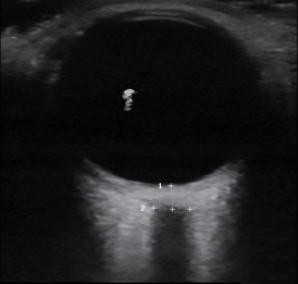

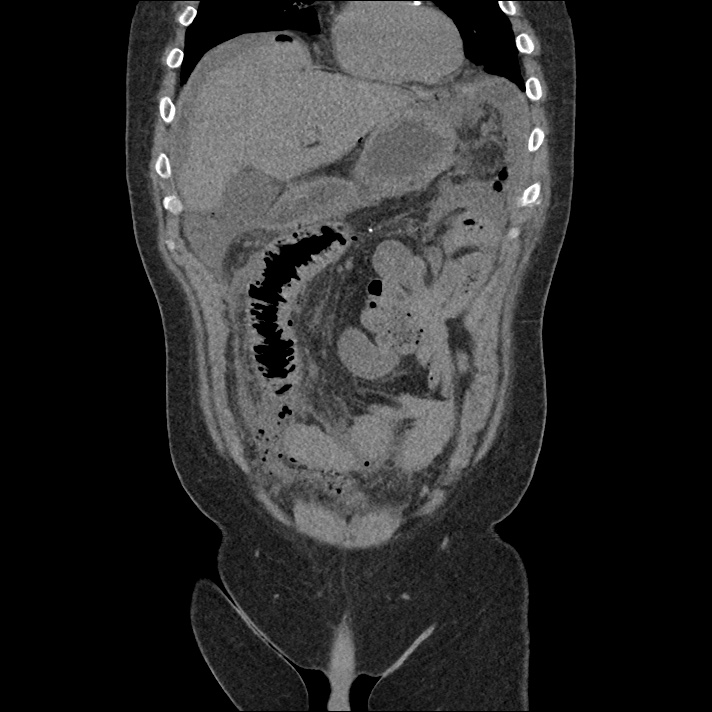

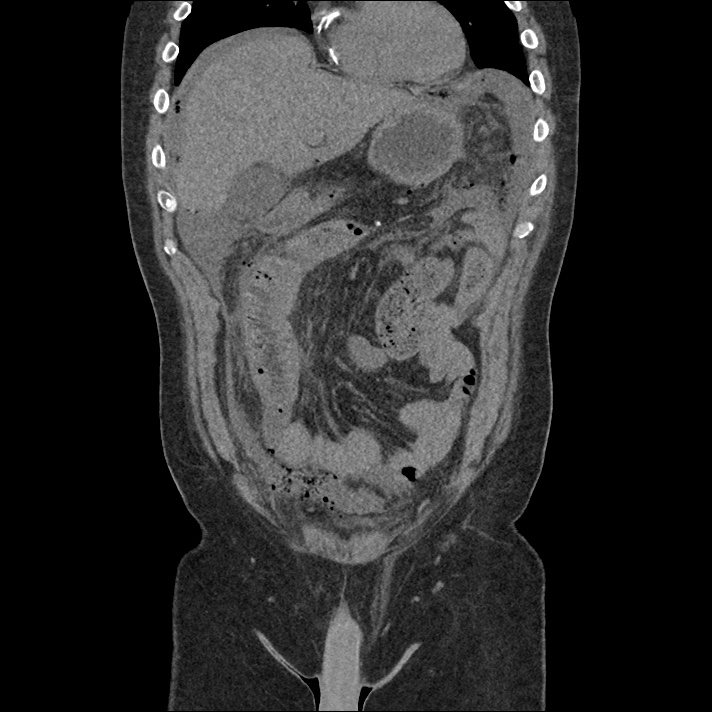

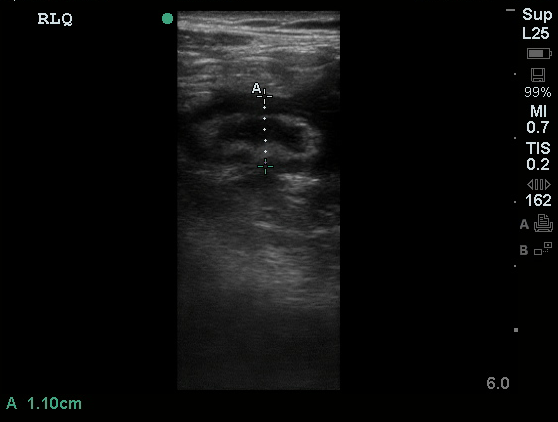

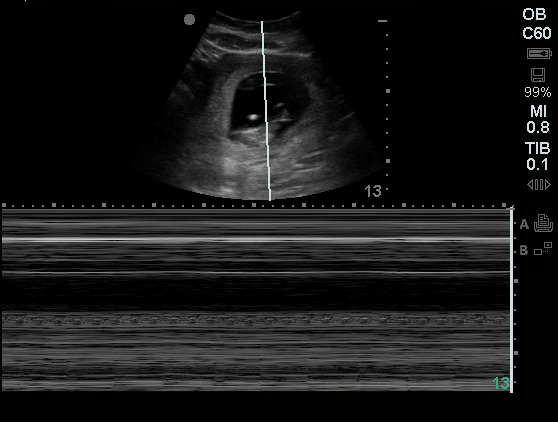

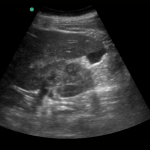

Gallstones

Many gallstones

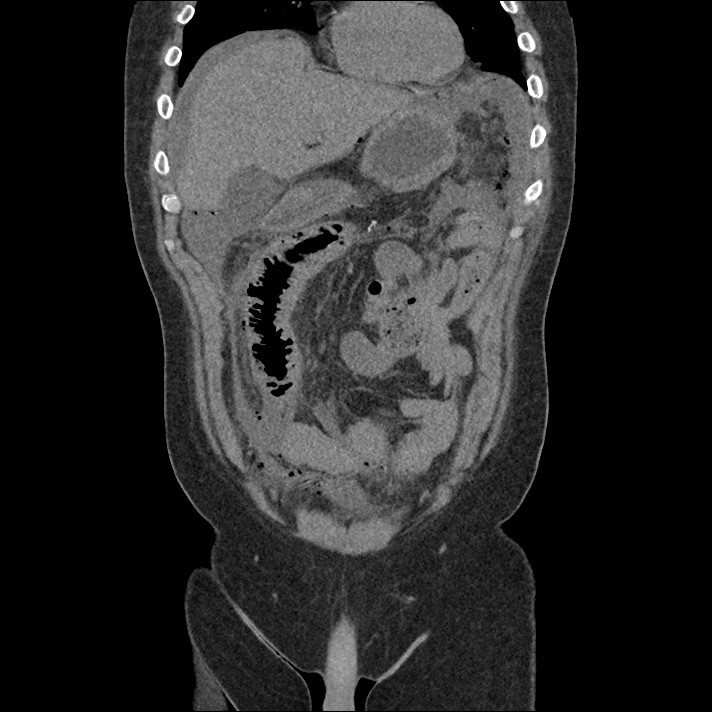

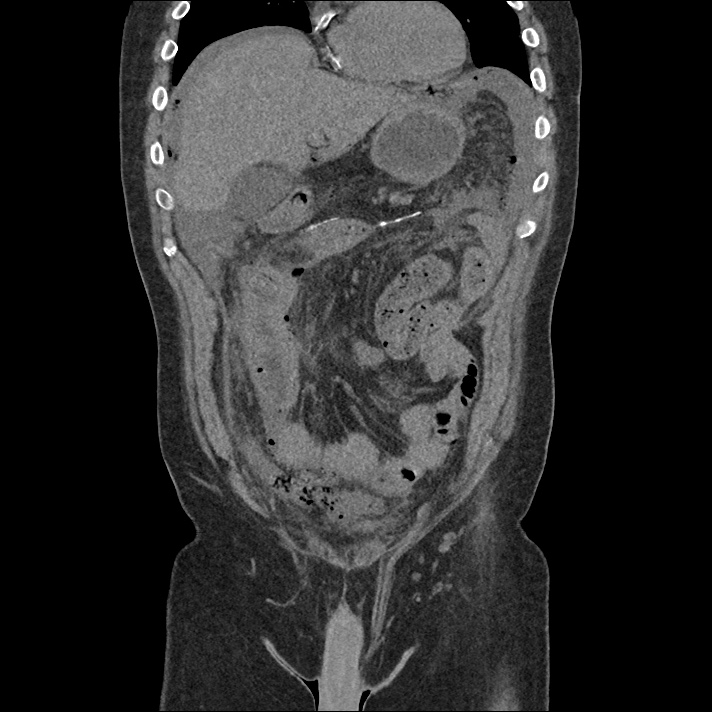

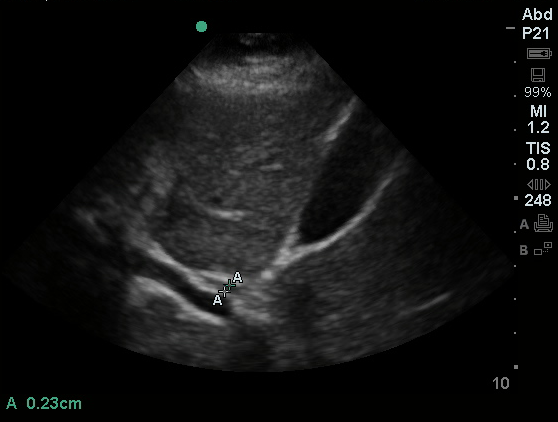

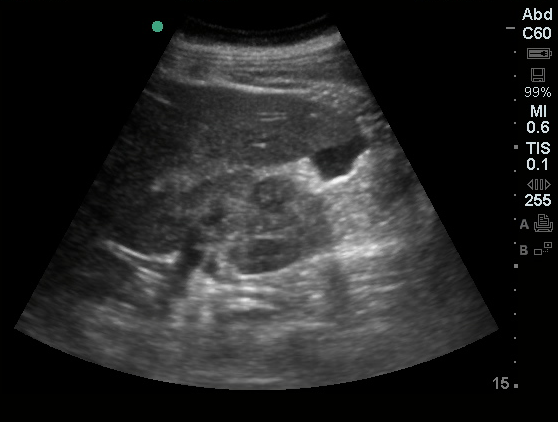

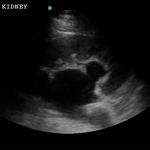

Gallbladder wall thickening

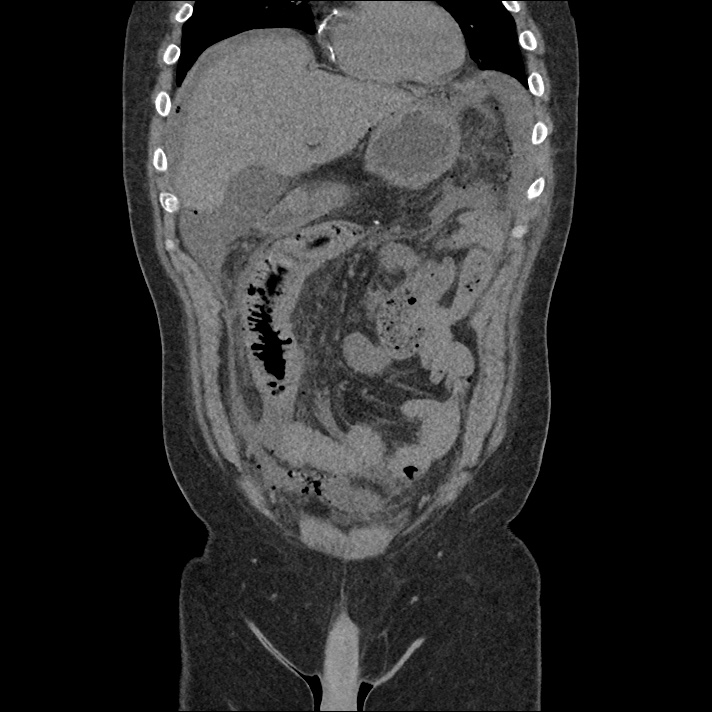

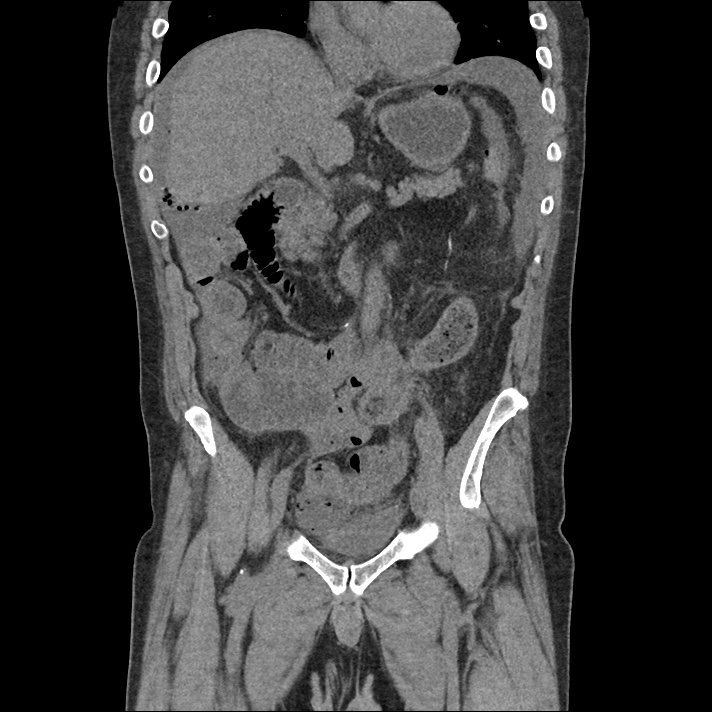

Pericholecystic fluid

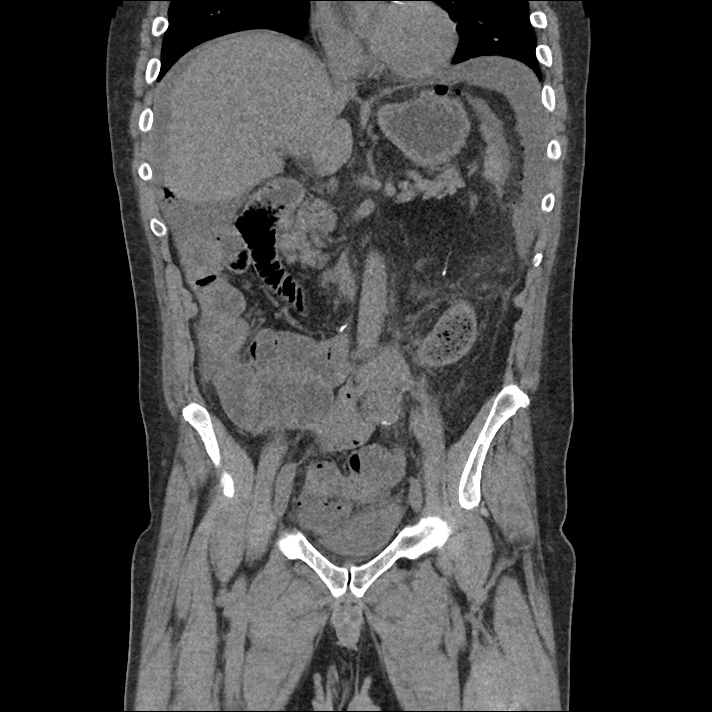

Choledocholithiasis

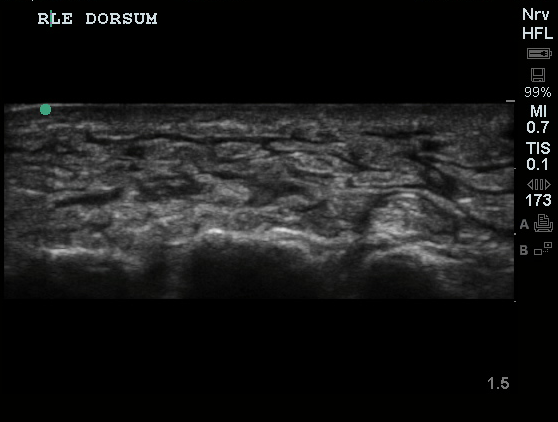

Common bile duct dilation

All illustrations are available for free, licensed (along with all content on this site) under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Public License.

Downloads Page License

References

- Trowbridge RL, Rutkowski NK, Shojania KG. Does this patient have acute cholecystitis? JAMA. 2003;289(1):80-86.

- Scruggs W, Fox JC, Potts B, et al. Accuracy of ED Bedside Ultrasound for Identification of gallstones: retrospective analysis of 575 studies. West J Emerg Med. 2008;9(1):1-5.

- Ross M, Brown M, McLaughlin K, et al. Emergency physician-performed ultrasound to diagnose cholelithiasis: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(3):227-235. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01012.x.

- Jang T, Chauhan V, Cundiff C, Kaji AH. Assessment of emergency physician-performed ultrasound in evaluating nonspecific abdominal pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(5):457-460. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2014.01.004.

- Kendall JL, Shimp RJ. Performance and interpretation of focused right upper quadrant ultrasound by emergency physicians. J Emerg Med. 2001;21(1):7-13.

- Summers SM, Scruggs W, Menchine MD, et al. A prospective evaluation of emergency department bedside ultrasonography for the detection of acute cholecystitis. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(2):114-122. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.01.014.

- Rubens DJ. Ultrasound Imaging of the Biliary Tract. Ultrasound Clinics. 2007;2(3):391-413. doi:10.1016/j.cult.2007.08.007.

- Rosen CL, Brown DF, Chang Y, et al. Ultrasonography by emergency physicians in patients with suspected cholecystitis. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2001;19(1):32-36. doi:10.1053/ajem.2001.20028.

- Shea JA. Revised Estimates of Diagnostic Test Sensitivity and Specificity in Suspected Biliary Tract Disease. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154(22):2573-2581. doi:10.1001/archinte.1994.00420220069008.

- Miller AH, Pepe PE, Brockman CR, Delaney KA. ED ultrasound in hepatobiliary disease. J Emerg Med. 2006;30(1):69-74. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.03.017.

- Shah K, Wolfe RE. Hepatobiliary ultrasound. Emergency Medicine Clinics of NA. 2004;22(3):661–73–viii. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2004.04.015.

- Matcuk GR, Grant EG, Ralls PW. Ultrasound measurements of the bile ducts and gallbladder: normal ranges and effects of age, sex, cholecystectomy, and pathologic states. Ultrasound Q. 2014;30(1):41-48. doi:10.1097/RUQ.0b013e3182a80c98.

- Engel JM, Deitch EA, Sikkema W. Gallbladder wall thickness: sonographic accuracy and relation to disease. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1980;134(5):907-909. doi:10.2214/ajr.134.5.907.

- Gerstenmaier JF, Hoang KN, Gibson RN. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound in gallbladder disease: a pictorial review. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2016;41(8):1640-1652. doi:10.1007/s00261-016-0729-4.

- Becker BA, Chin E, Mervis E, Anderson CL, Oshita MH, Fox JC. Emergency biliary sonography: utility of common bile duct measurement in the diagnosis of cholecystitis and choledocholithiasis. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(1):54-60. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.03.024.