Overview

Laryngoscopy had until recently remained relatively unchanged since the introduction of the Macintosh and Miller blades in the 1940’s. Advancements in fiberoptic technology have led to the development of multiple novel devices obviating line-of-sight requirements for direct laryngoscopy which may aid with endotracheal intubation in some populations. While there is no evidence to suggest that video laryngoscopy improves patient-centered outcomes, familiarity with the technique of video laryngoscopy is a critical educational objective for trainees who should be comfortable in the use of this and other rescue airway management adjuncts.

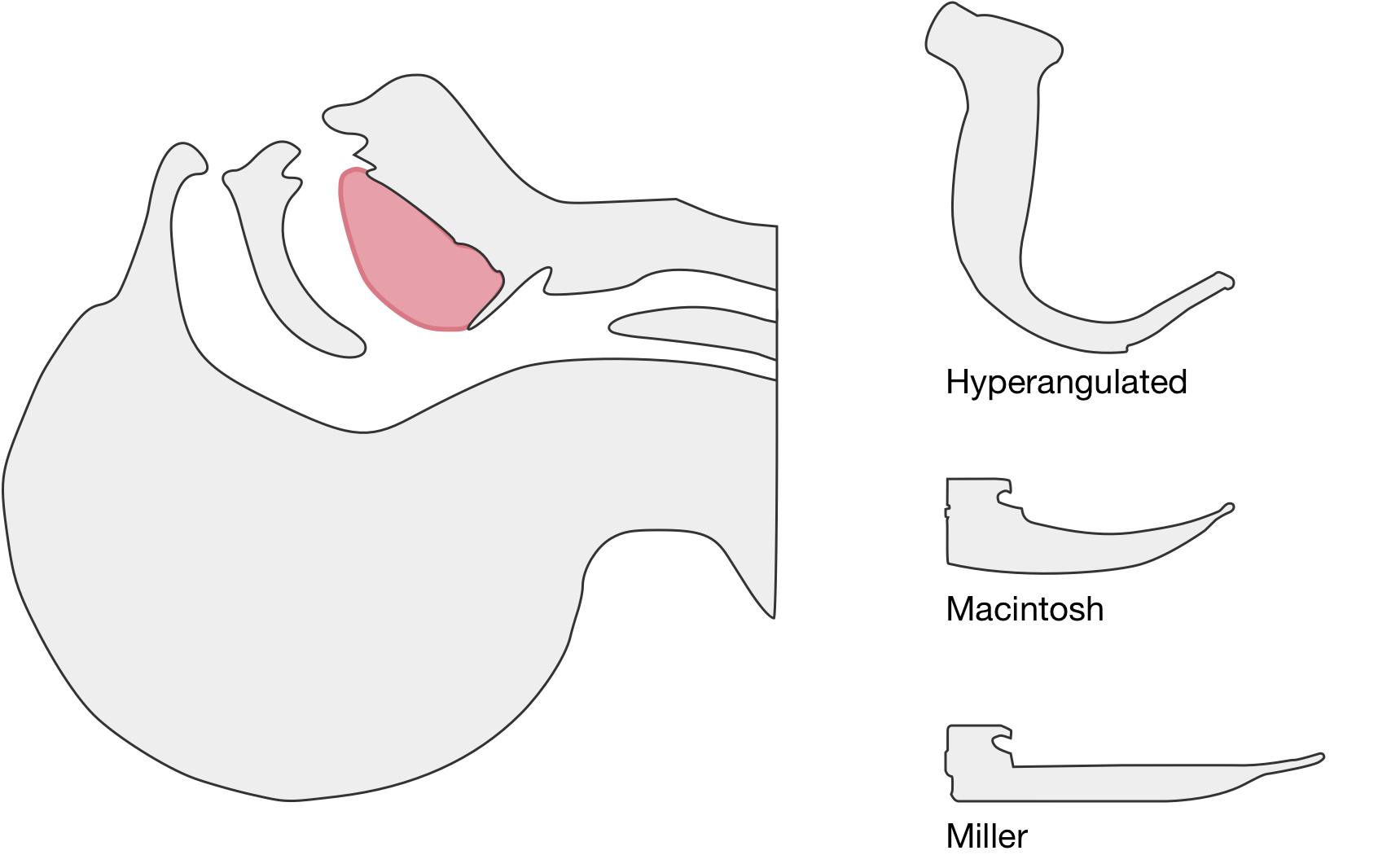

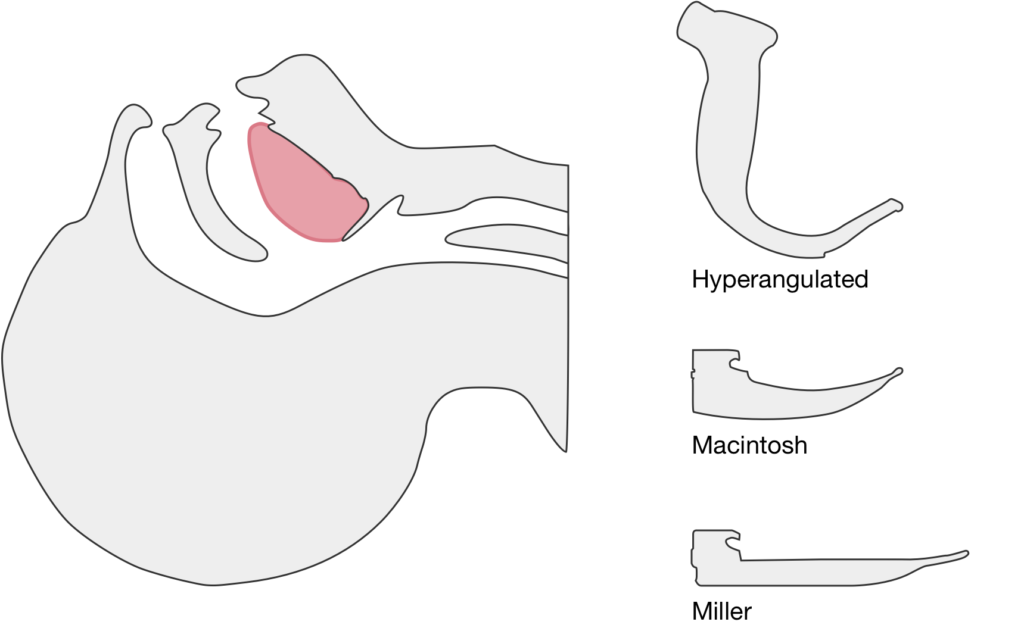

The image above shows a comparison of the curvature of straight (Miller), curved (Macintosh) and hyperangulated blades relative to the oral, pharyngeal and laryngeal axes. The hyperangulated blade easily positions a fiberoptic camera over the glottic opening, allowing easy visualization of the vocal cords. Passing the endotracheal tube without direct line-of-sight becomes the challenge of intubation.

The purpose of this guide is to explore the differences in technique for performing video laryngoscopy compared to direct laryngoscopy. Specifically, the guide is focused on video laryngoscopes with hyper-angulated blades (Verathon Glidescope, Storz C-MAC D-Blade) as these devices pose more challenges for appropriate use while potentially offering the greatest advantages for glottic visualization in challenging airway management.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Advantages1

- Improved glottic visualization especially in scenarios with limited neck mobility as there is no need to align the oral-pharyngeal-laryngeal axes.

- Allows others to view the screen and facilitate endotracheal intubation.

Disadvantages1

- Difficulty passing endotracheal tube despite improved glottic visualization.

- Obscured view by fogging or contaminated airway (blood, secretions, vomit).

- Possibility for deterioration of skills in direct laryngoscopy.

Technique

Blade Insertion

Because of it’s unique shape, special care should be taken when inserting a hyperangulated blade to avoid dental/oropharyngeal injury. The handle of the blade may need to be angled towards the patient’s chest and turned slightly to facilitate atraumatic insertion.

Blade Advancement

Transition to viewing the screen once the tip of the blade is past the visualized posterior portion of the tongue. Advance the blade along the base of the tongue while monitoring the view on screen. Identify the epiglottis and guide the tip of the blade into the vallecula, the objective is to center the glottic aperture in the upper 2/3 of the screen.

Optimal View

The optimal view shows the vocal cords centered in the upper 2/3 of the screen. This provides adequate screen “real estate” to show the endotracheal tube entering the screen and provide more visual feedback as the tube position is manipulated.

Blade Adjustment

The shape of the hyperangulated blade means that visualizing the airway is less dependent on the lifting motion applied with direct laryngoscopy. Instead, angulating the tip of the blade upward by gently rocking the handle back (taking great care to avoid dental/oropharyngeal trauma) will dramatically improve the view.

Endotracheal Tube Insertion

Directly visualize the insertion of the endotracheal tube into the oral cavity. The endotracheal tube should be loaded with an appropriately angulated rigid stylet. Follow the curvature of the laryngoscope blade entering from the right corner of the mouth. When the endotracheal tube is passed along the edge of the laryngoscope blade, few adjustments will be required for successful endotracheal intubation.

Endotracheal Tube Position Adjustments

If the view is optimized but the endotracheal tube is off-center and does not directly pass the vocal cords into the trachea, subtle adjustments to the endotracheal tube can help guide it into position. Hold the endotracheal tube like a pencil, turning it slightly clockwise or counter-clockwise between your index finger and thumb to manipulate the distal tip left or right above the laryngeal opening.

Stylet Removal

Once past the vocal cords, the hyperangulated rigid stylet will limit continued passage of the endotracheal tube into the trachea as it will get stuck on the anterior surface of the trachea. To facilitate easy passage into the trachea, the stylet should be pulled back slightly to allow passage into the trachea before being fully removed and the tube secured in position.

Review of Evidence

Emergency Department:

- C-MAC associated with higher rate of successful intubation and greater proportion of grade I-II Cormack-Lehane views compared to direct laryngoscopy.5

- Glidescope associated with higher rate of successful intubation (and fewer esophageal complications) compared to direct laryngoscopy. 6

- Glidescope associated with higher rate of successful intubation compared to direct laryngoscopy. 7

Adjustments to Challenging Tube Placement:

- Combination of flexible-tipped endotracheal tube with rigid stylet (Verathon GlideRight stylet) may increase intubation success.8

- No apparent benefit to “reverse camber” loading of stylet into endotracheal tube. Reverse camber loading references placing the angled stylet 180° opposite to the natural curvature of the endotracheal tube.9

- If a malleable stylet is used, 90° angulation was associated with higher rates of successful intubation. 10

Recent Data:

- Propensity score-matched analysis of multicenter emergency department airway registry – no significant difference in rates of successful intubation comparing Glidescope to direct laryngoscopy. 11

- Randomized trial comparing direct and video laryngoscopy using C-MAC showed no difference in rates of successful intubation, duration of intubation attempt, aspiration events or length of hospitalization. For interventions randomized to direct laryngoscopy, the video laryngoscope screen was covered. 12

Meta-Analyses:

- Meta-analysis (predominantly for intubations in the operating room) suggests video laryngoscopy associated with fewer failed intubations, particularly among patients with anticipated difficult airway. Insufficient evidence to analyze effects on incidence of hypoxia, respiratory complications, time to intubation, or mortality.13

References

- Maldini B, Hodžović I, Goranović T, Mesarić J. CHALLENGES IN THE USE OF VIDEO LARYNGOSCOPES. Acta Clin Croat. 2016;55 Suppl 1:41-50. doi:10.20471/acc.2016.55.s1.05.

- Levitan RM, Heitz JW, Sweeney M, Cooper RM. The complexities of tracheal intubation with direct laryngoscopy and alternative intubation devices. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57(3):240-247. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.05.035.

- Hurford WE. The video revolution: a new view of laryngoscopy. Respir Care. 2010;55(8):1036-1045.

- Cheyne DR, Doyle P. Advances in laryngoscopy: rigid indirect laryngoscopy. F1000 Med Rep. 2010;2:61. doi:10.3410/M2-61.

- Sakles JC, Mosier J, Chiu S, Cosentino M, Kalin L. A Comparison of the C-MAC Video Laryngoscope to the Macintosh Direct Laryngoscope for Intubation in the Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(6):739-748. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.03.031.

- Sakles JC, Mosier JM, Chiu S, Keim SM. Tracheal Intubation in the Emergency Department: A Comparison of GlideScope® Video Laryngoscopy to Direct Laryngoscopy in 822 Intubations. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(4):400-405. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.05.019.

- MD JMM, MPH USP, BA SC, MD JCS. Difficult Airway Management in the Emergency Department: GlideScope Videolaryngoscopy Compared to Direct Laryngoscopy. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(6):629-634. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.06.007.

- Radesic BP, Winkelman C, Einsporn R, Kless J. Ease of intubation with the Parker Flex-Tip or a standard Mallinckrodt endotracheal tube using a video laryngoscope (GlideScope). AANA J. 2012;80(5):363-372.

- Jones PM, Turkstra TP, Armstrong KP, et al. Effect of stylet angulation and endotracheal tube camber on time to intubation with the GlideScope. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth. 2007;54(1):21-27.

- Turkstra TP, Harle CC, Armstrong KP, et al. The GlideScope-specific rigid stylet and standard malleable stylet are equally effective for GlideScope use. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth. 2007;54(11):891-896.

- Choi HJ, Kim Y-M, Oh YM, et al. GlideScope video laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy in the emergency department: a propensity score-matched analysis. BMJ Open. 2015;5(5):e007884-e007884. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007884.

- Driver BE, Prekker ME, Moore JC, Schick AL, Reardon RF, Miner JR. Direct Versus Video Laryngoscopy Using the C-MAC for Tracheal Intubation in the Emergency Department, a Randomized Controlled Trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(4):433-439. doi:10.1111/acem.12933.

- Lewis SR, Butler AR, Parker J, Cook TM, Smith AF. Videolaryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for adult patients requiring tracheal intubation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:CD011136. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011136.pub2.