Brief HPI:

A 34-year-old male with a history of rheumatoid arthritis and interstitial lung disease presents to the emergency department with joint pain unimproved with home medications. He suspects the precipitant is a recent illness, describing cough and nasal congestion. He also noted a “crunching” sensation when turning his neck not otherwise associated with fevers, recurrent vomiting, chest pain, abdominal pain or difficulty breathing.

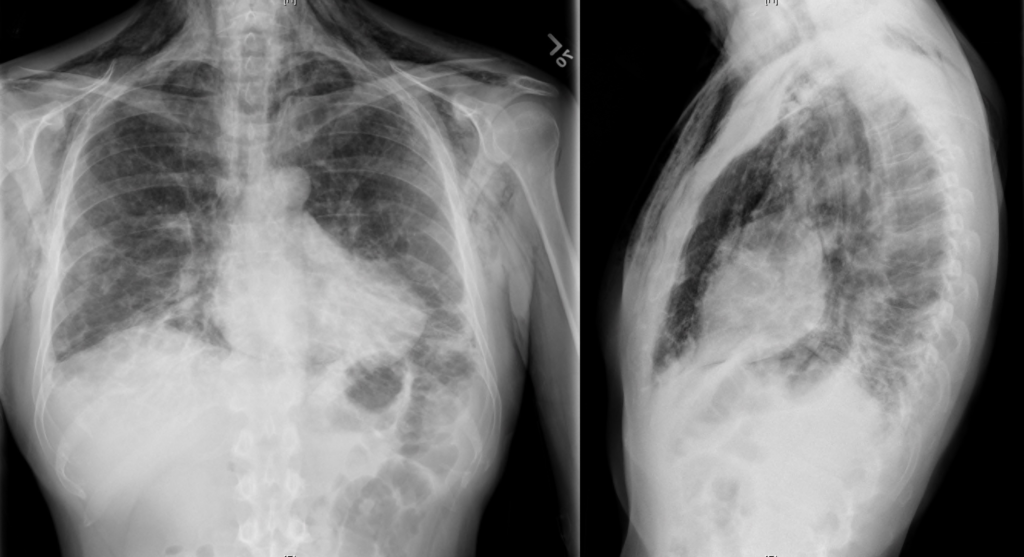

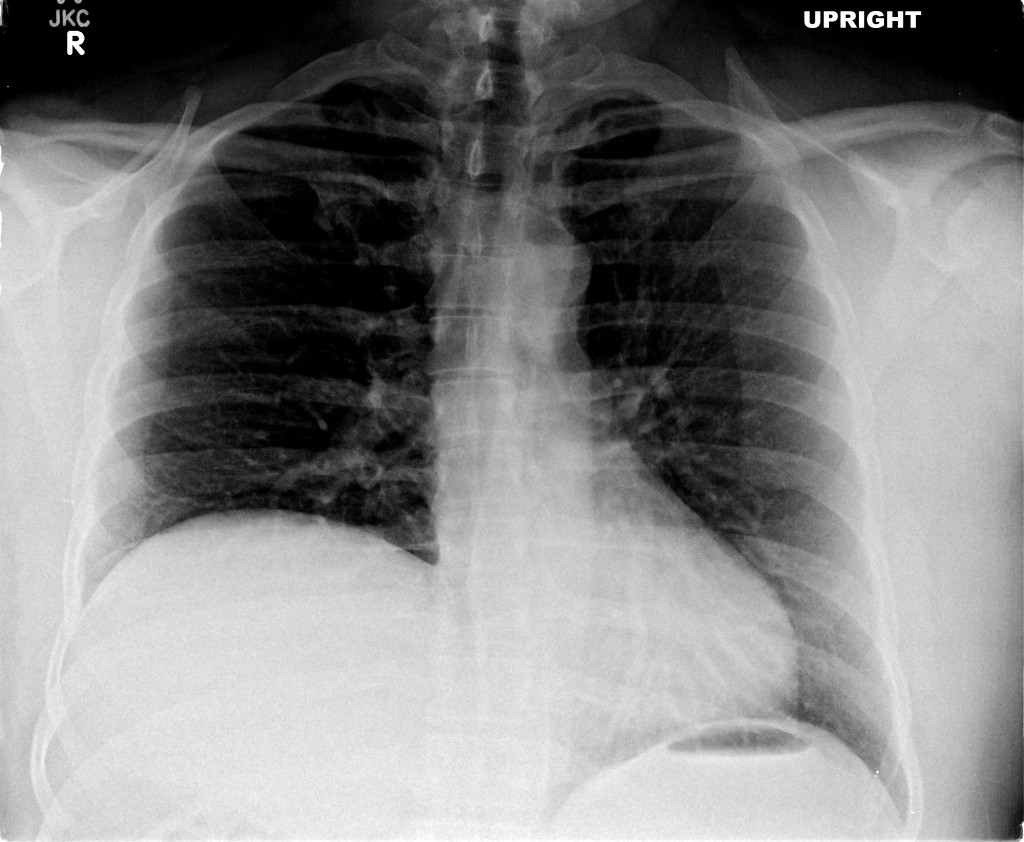

A chest radiograph was obtained which demonstrated pneumomediastinum.

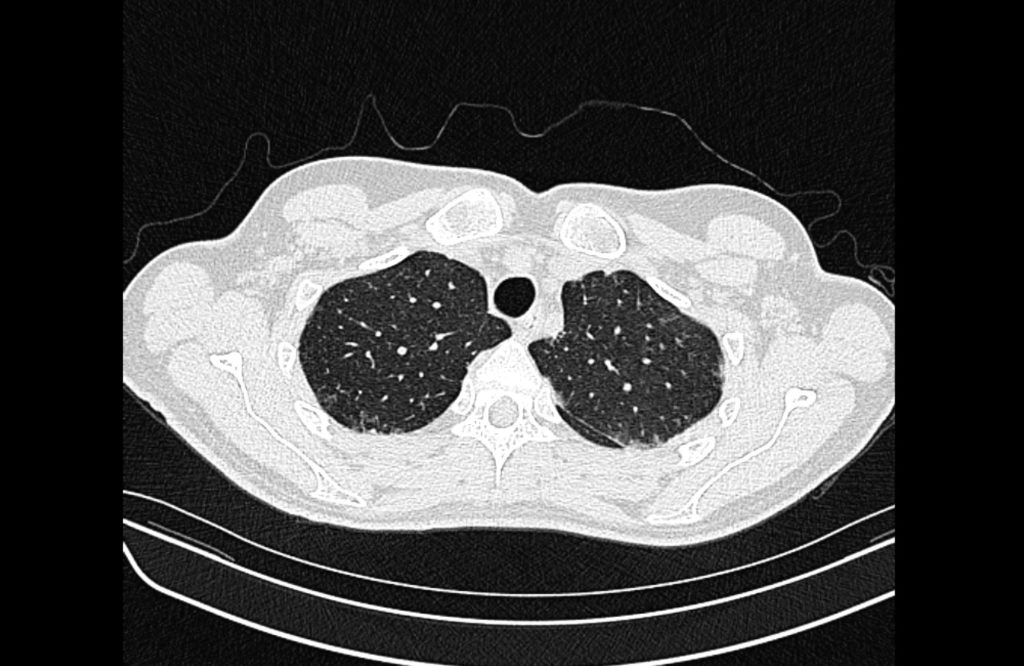

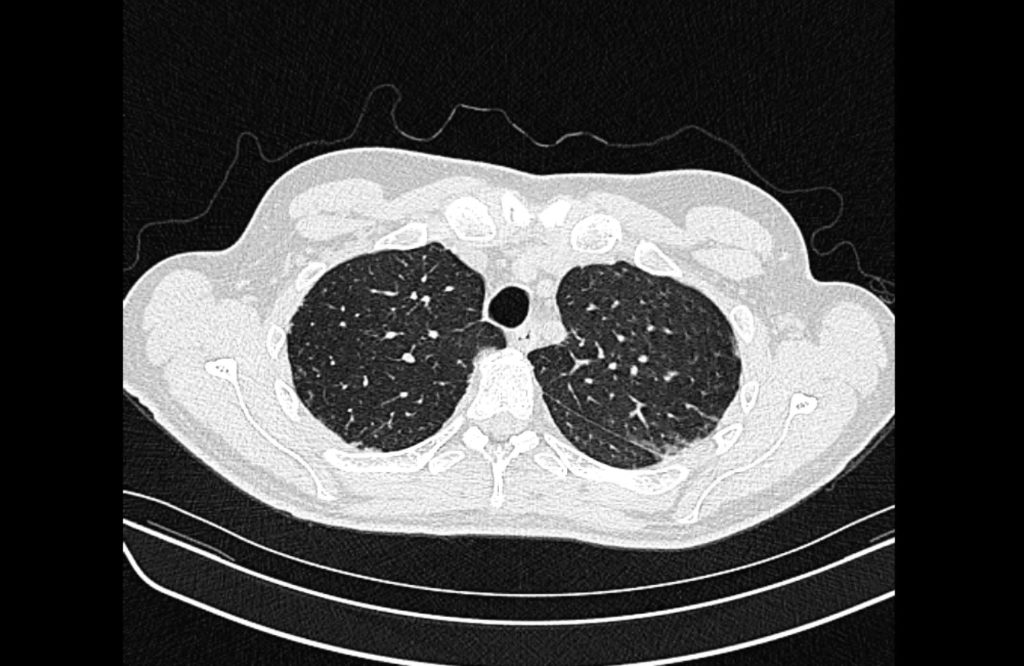

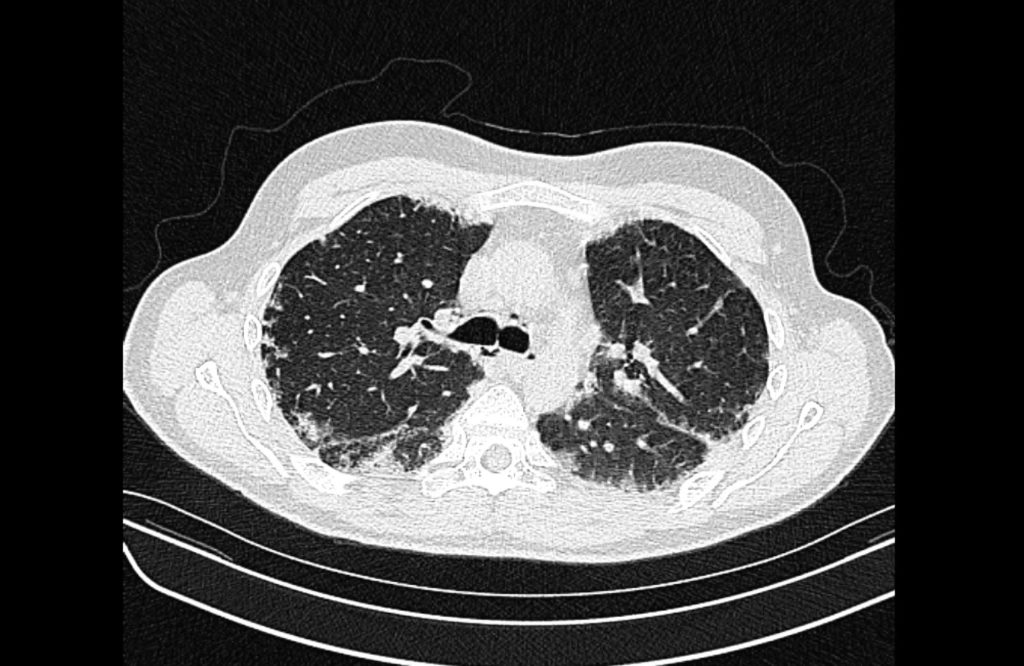

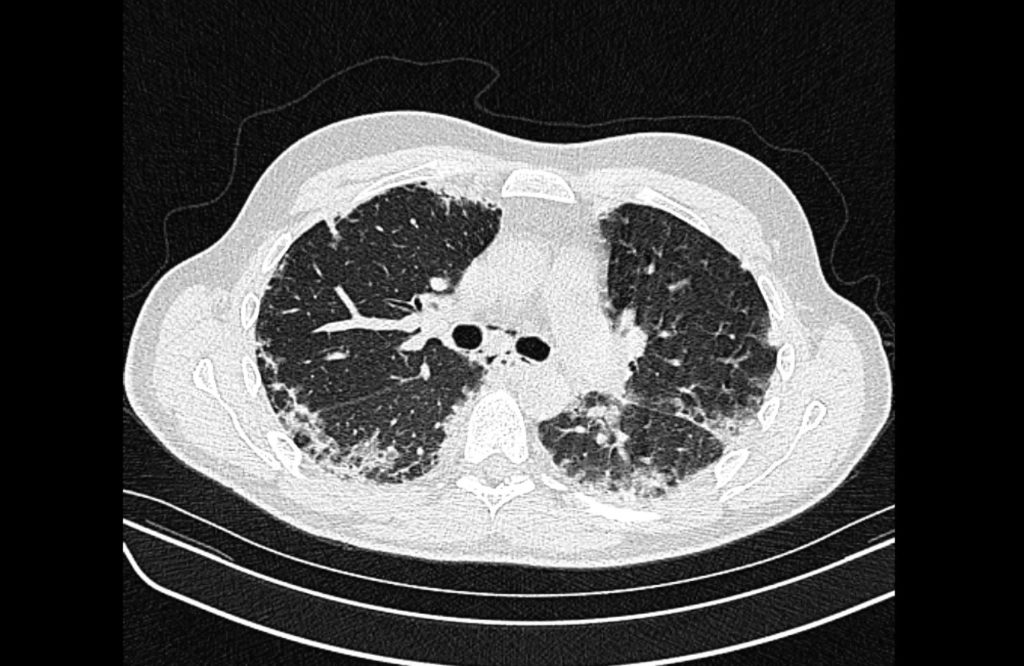

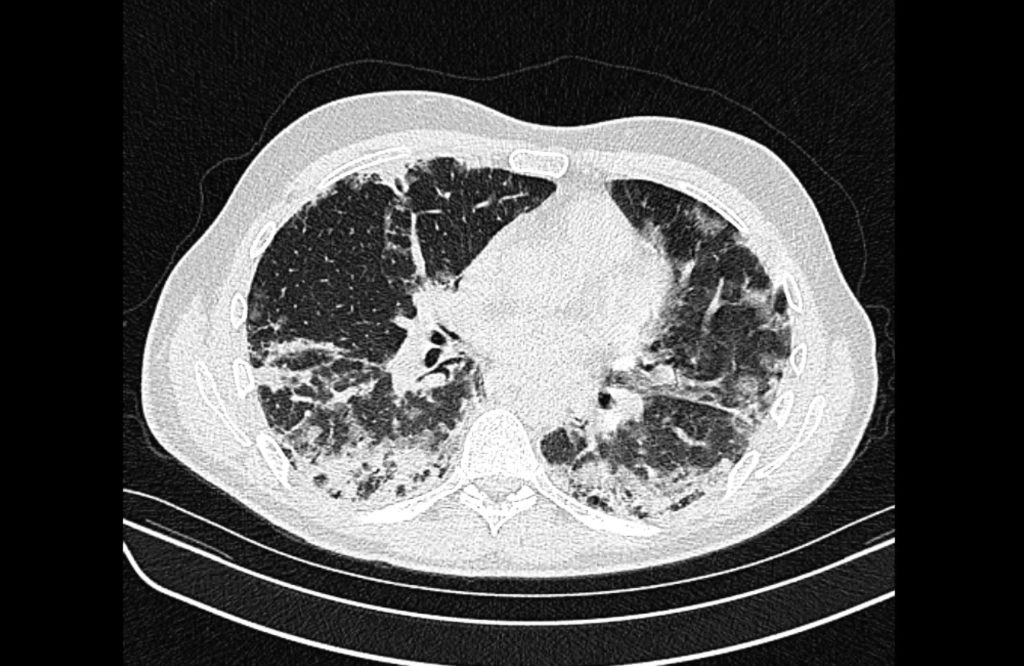

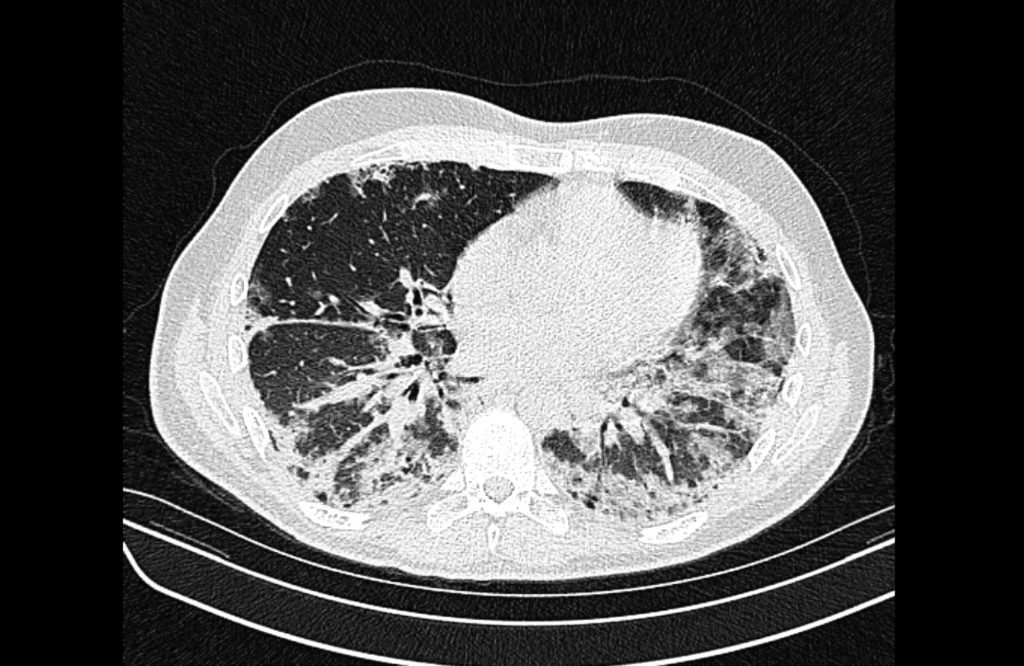

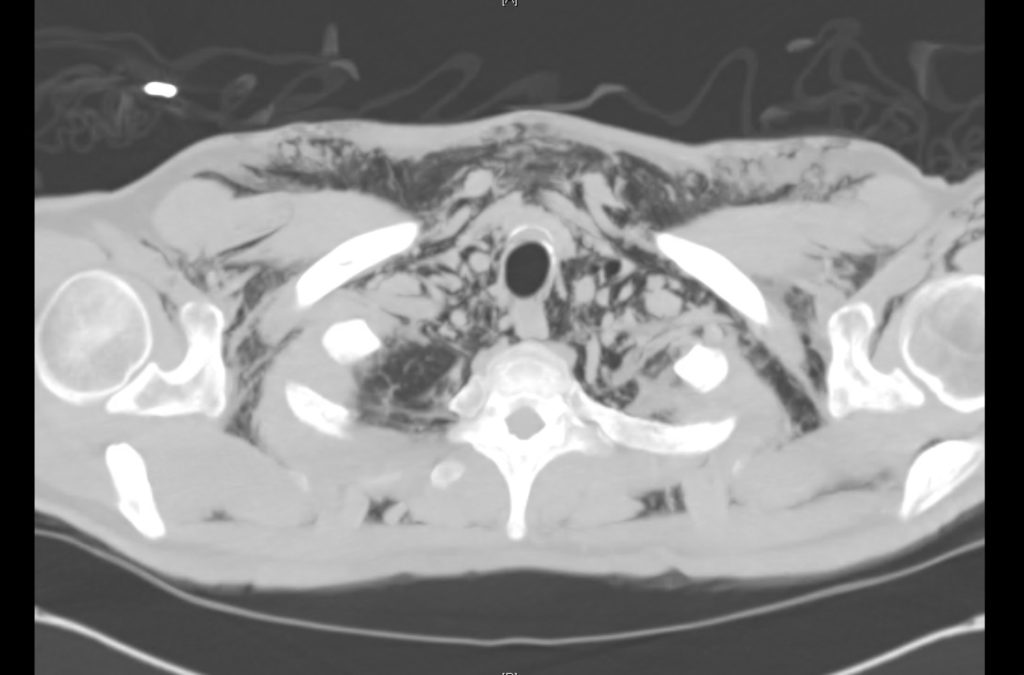

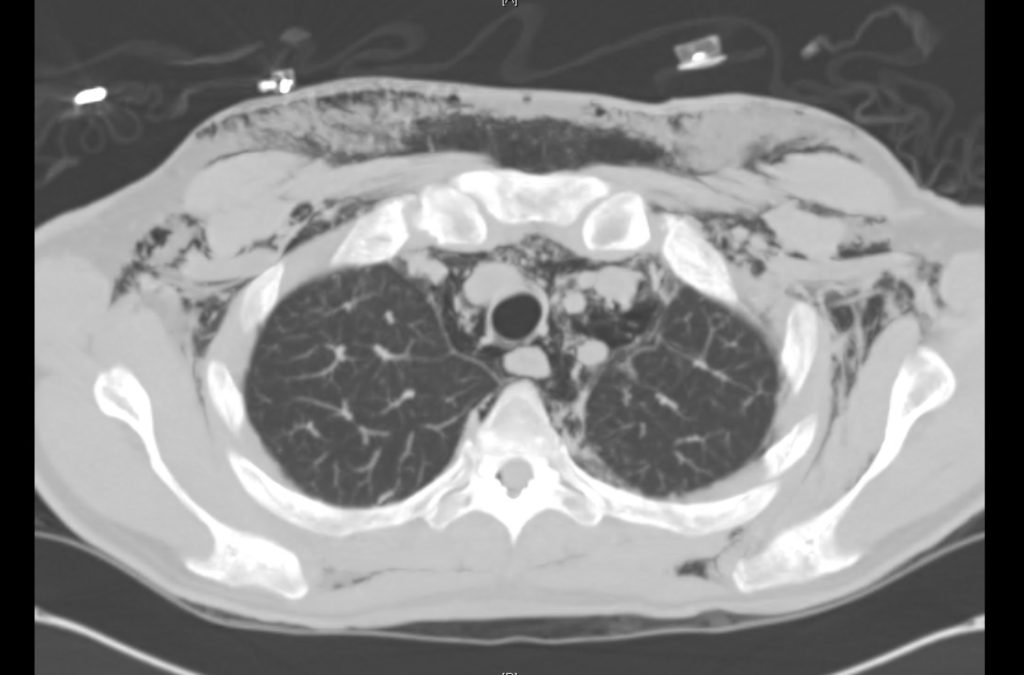

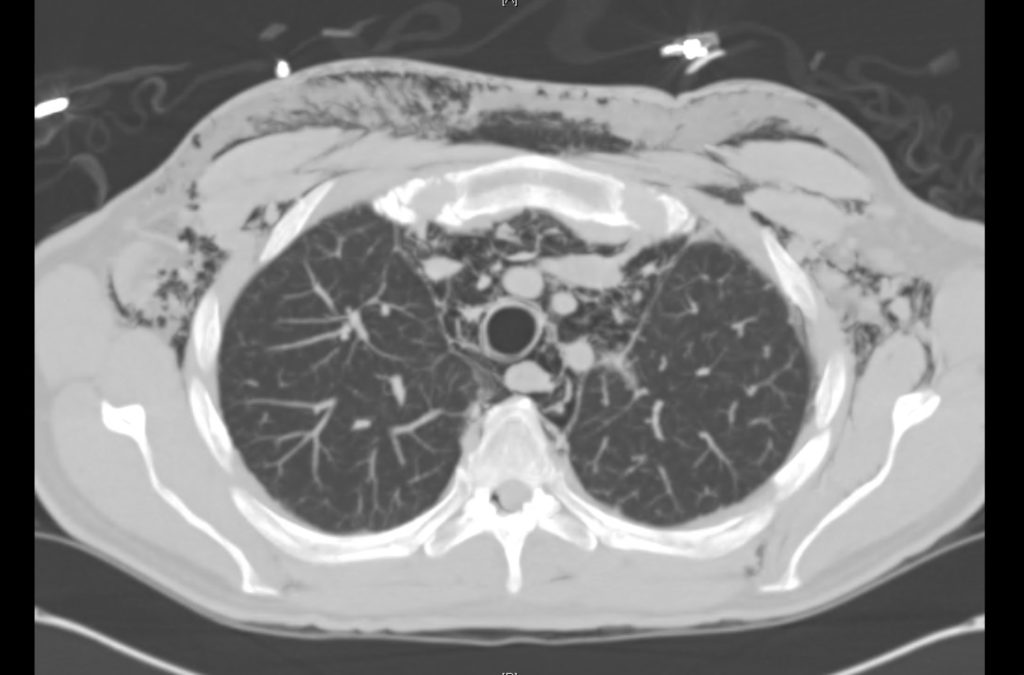

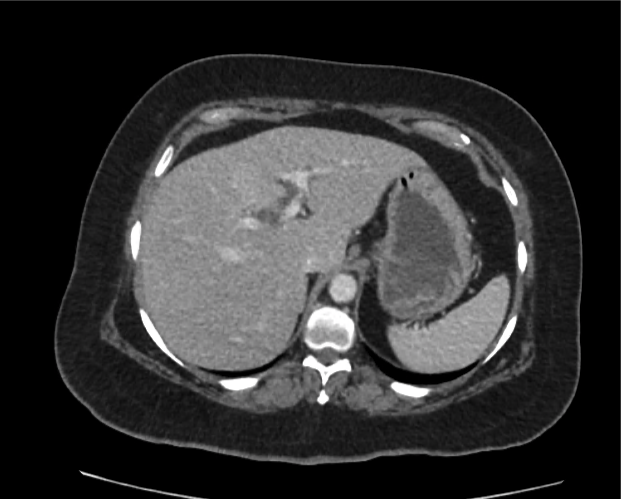

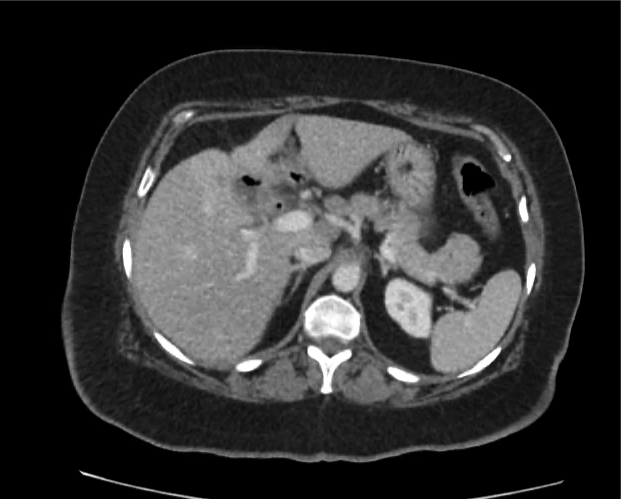

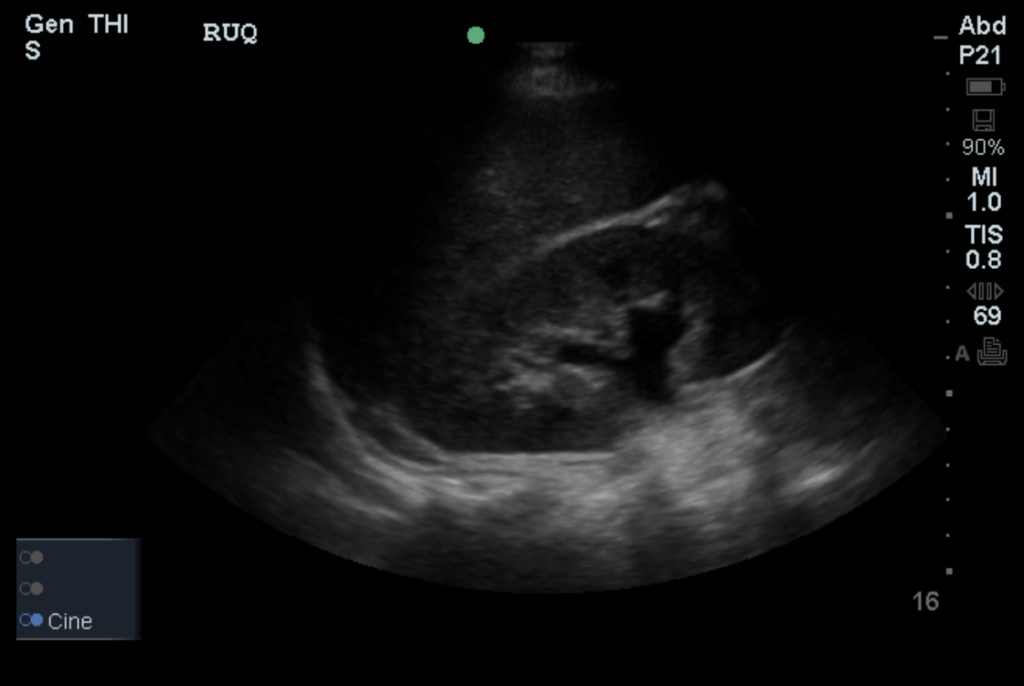

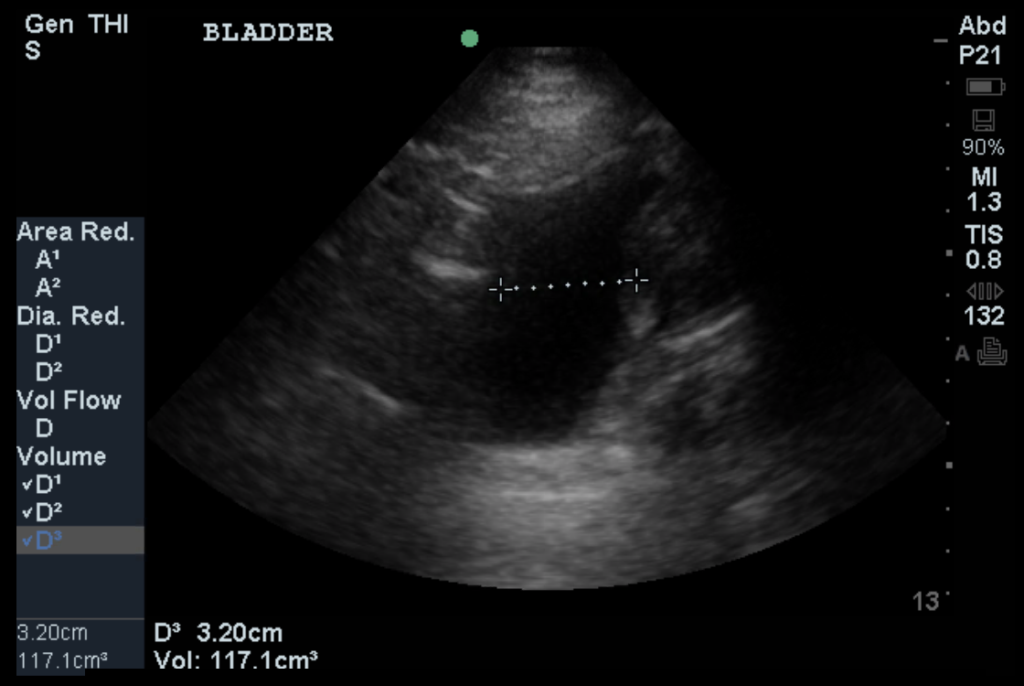

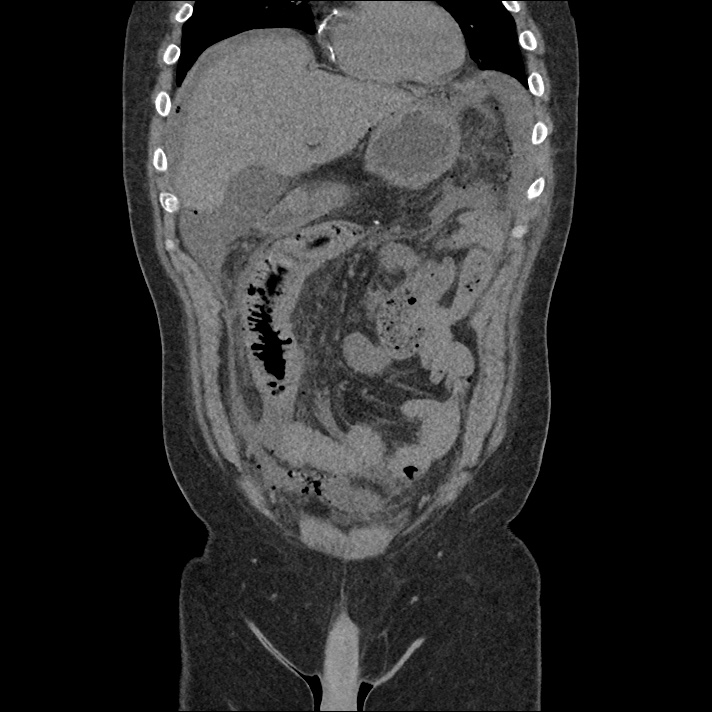

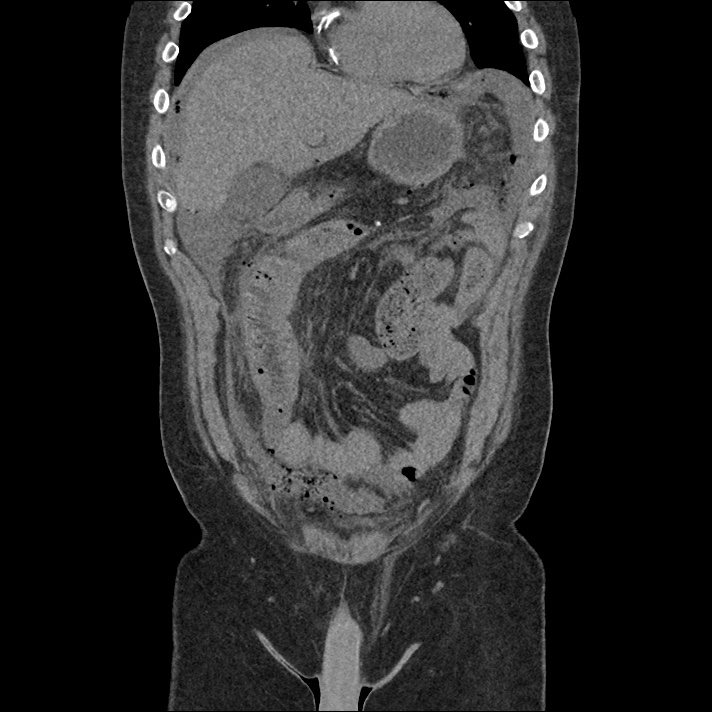

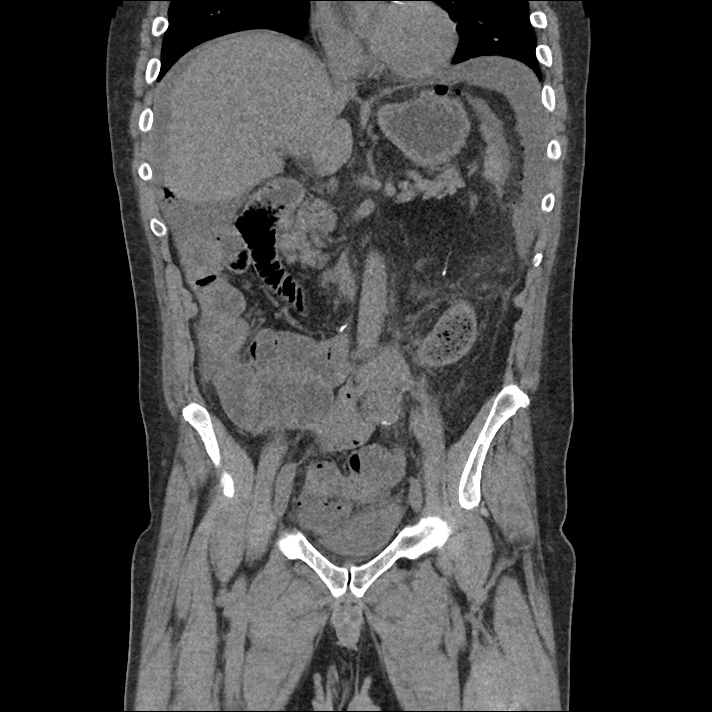

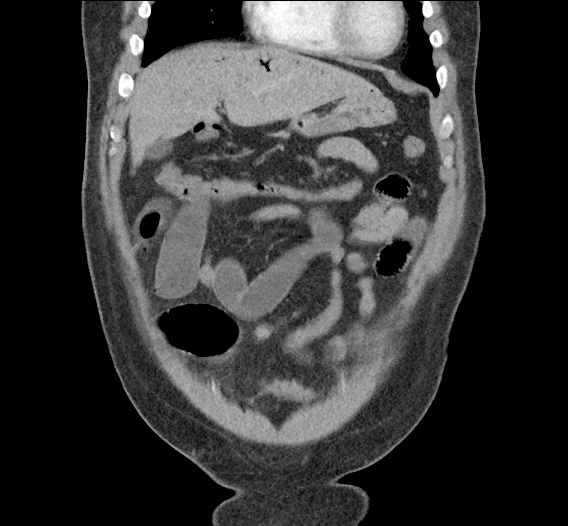

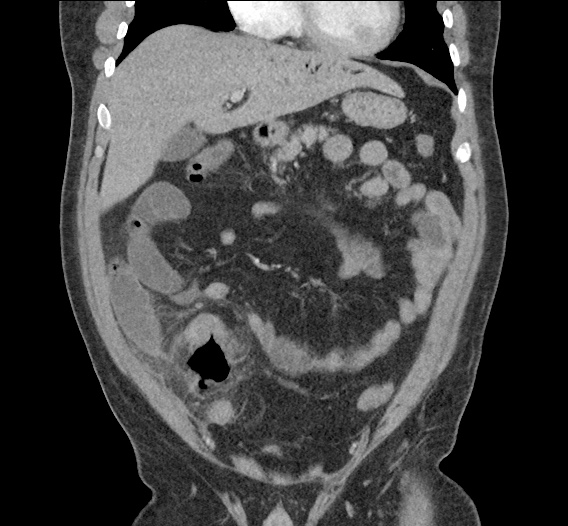

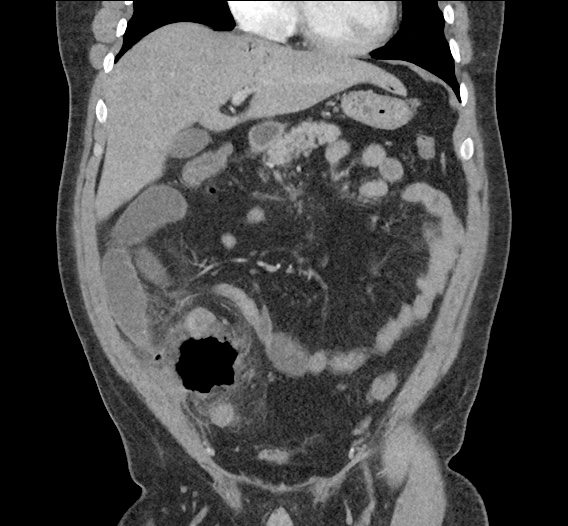

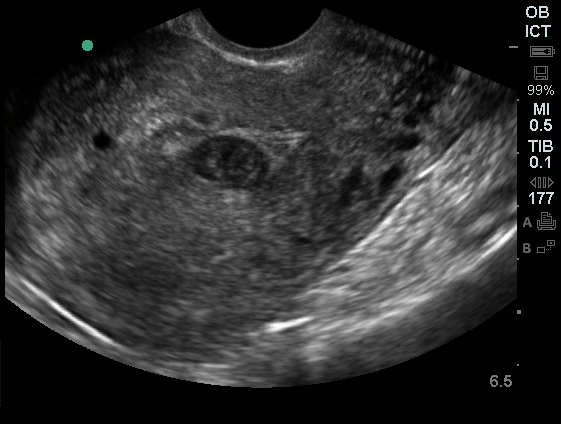

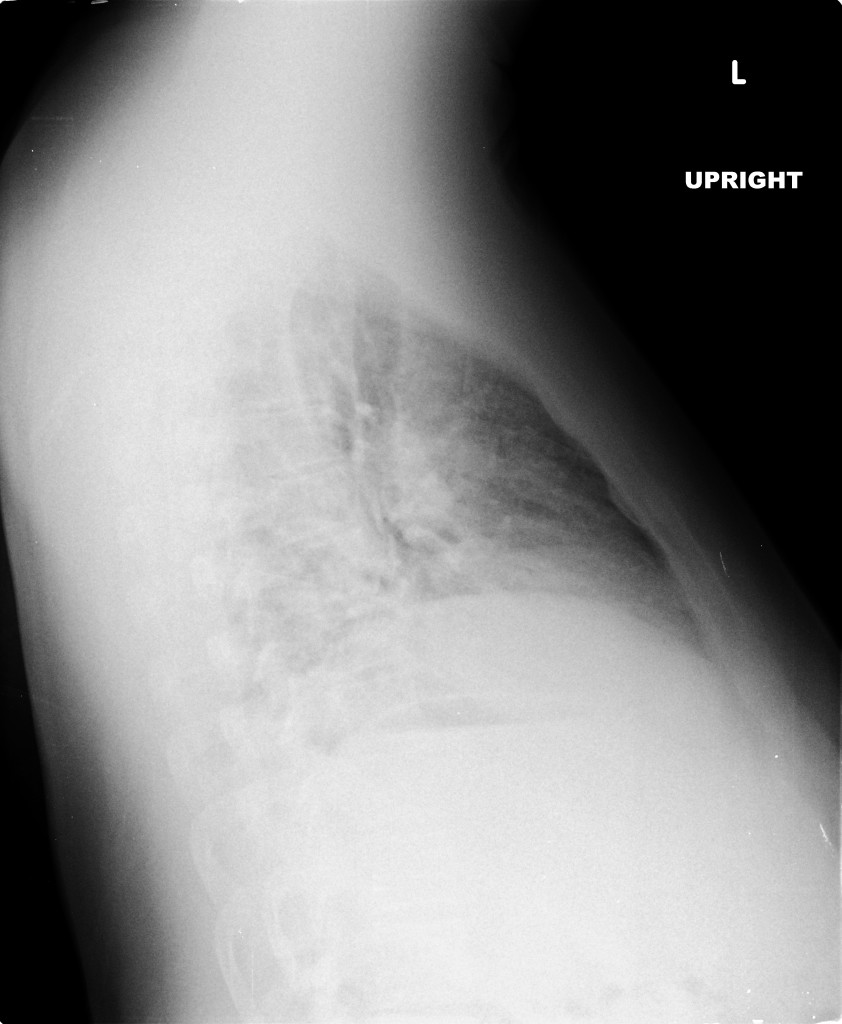

Imaging from several months prior to presentation is shown below:

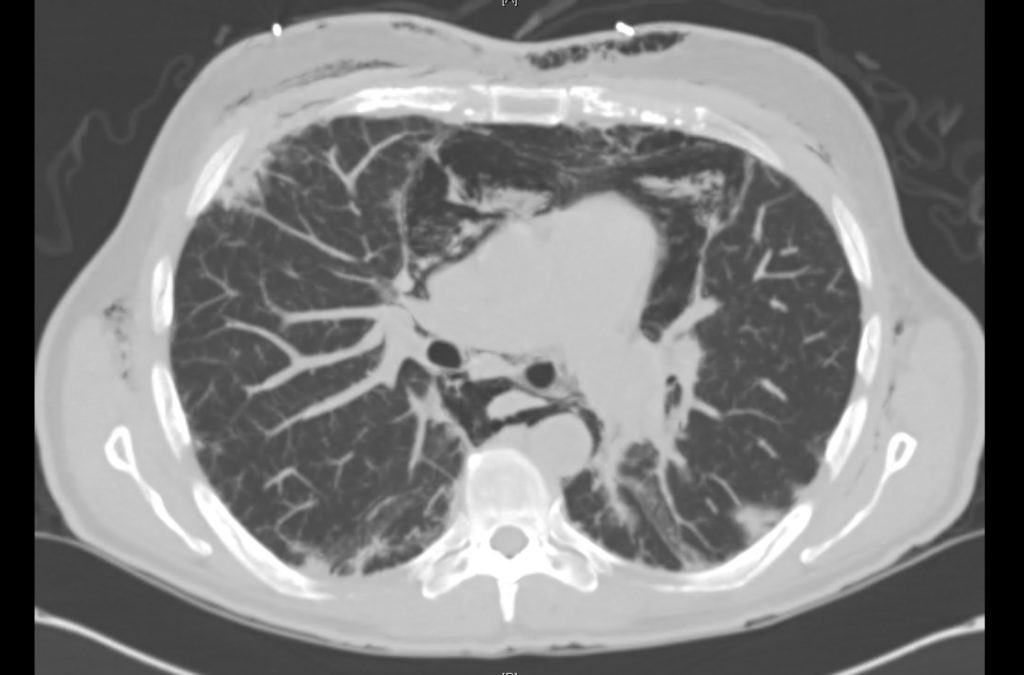

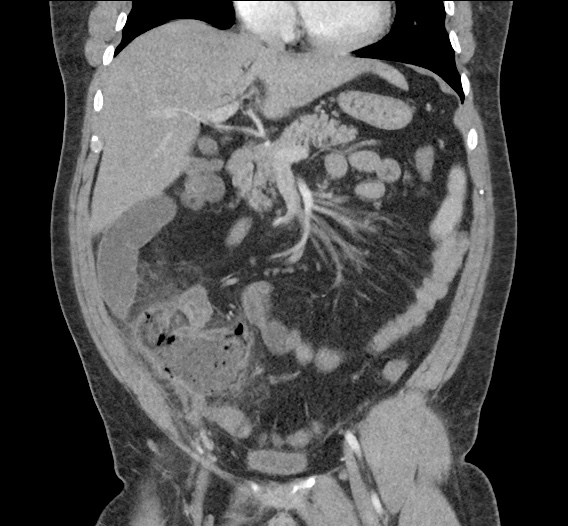

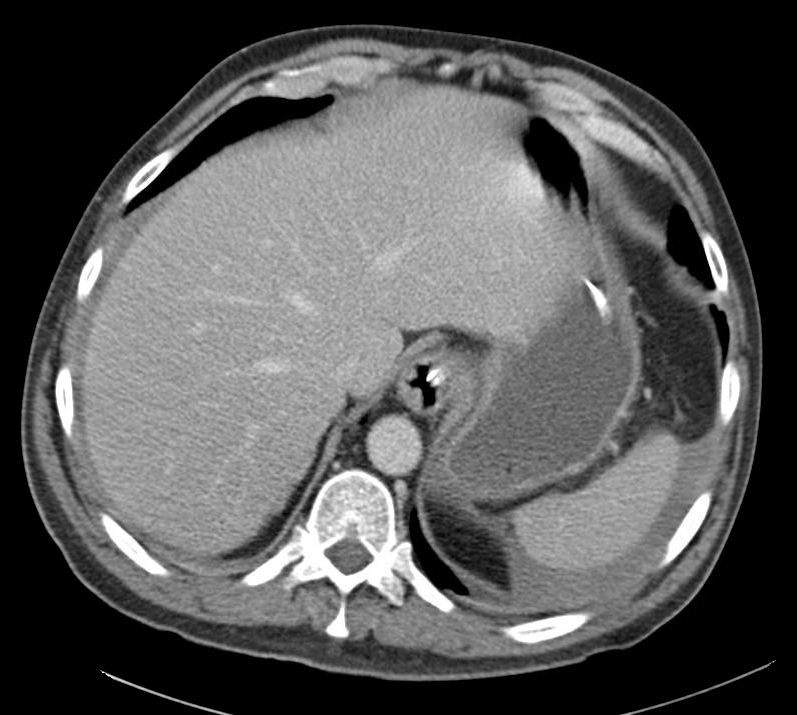

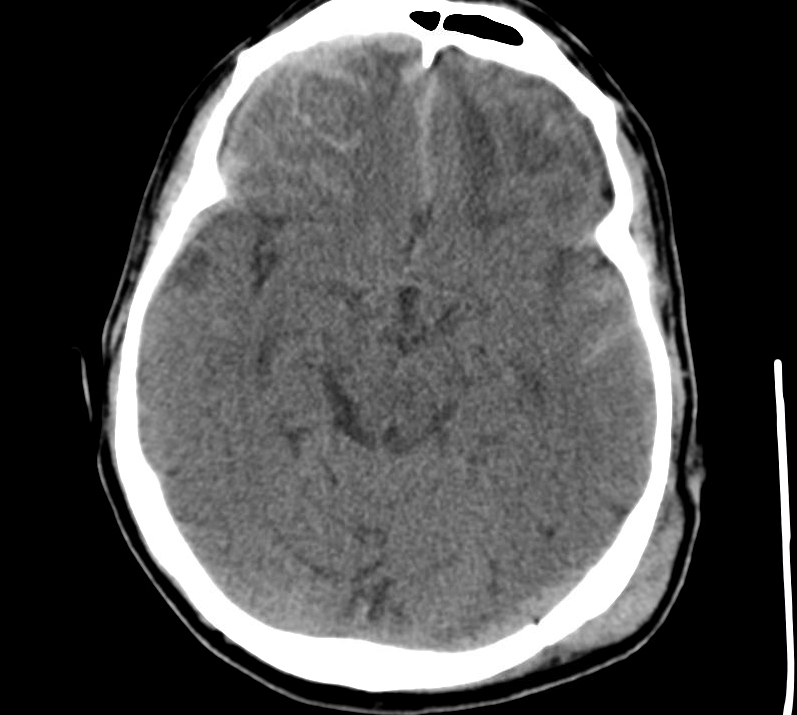

Prior CT Chest:

Extensive peripheral reticular and ground glass opacities and traction bronchiectasis predominates in the lower lobes. Imaging findings are most suggestive of usual interstitial pneumonia. Small focus of pneumomediastinum at carina.

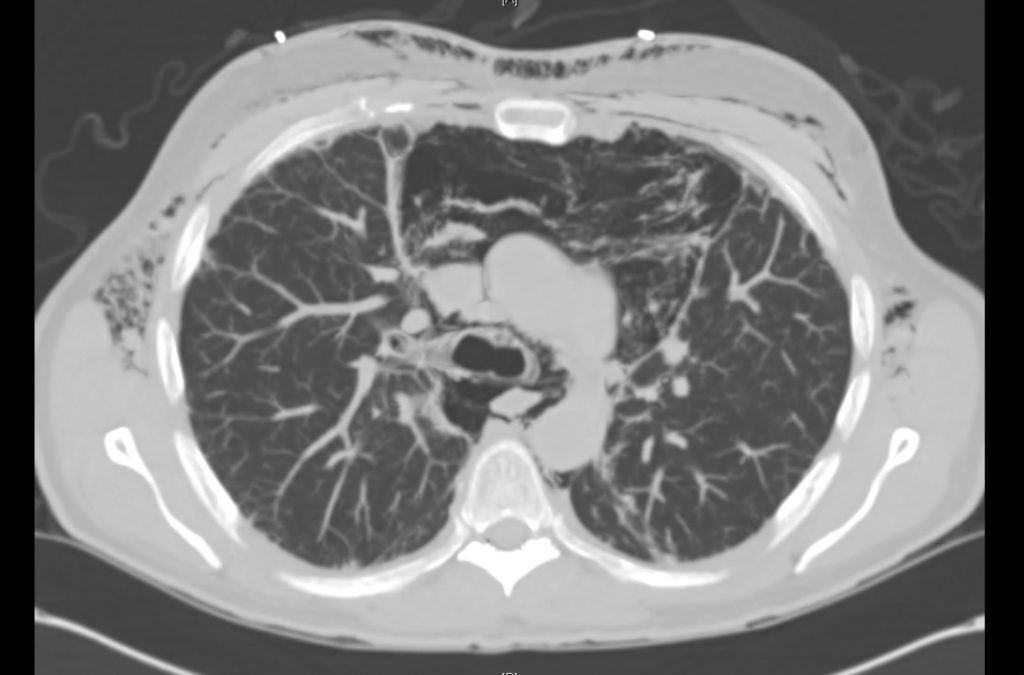

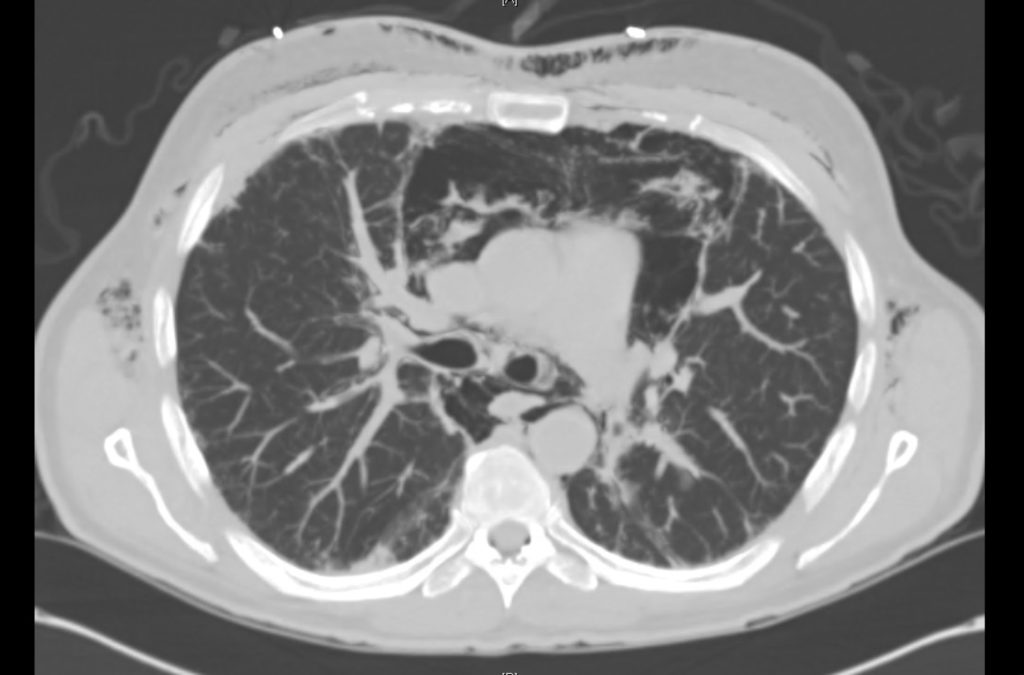

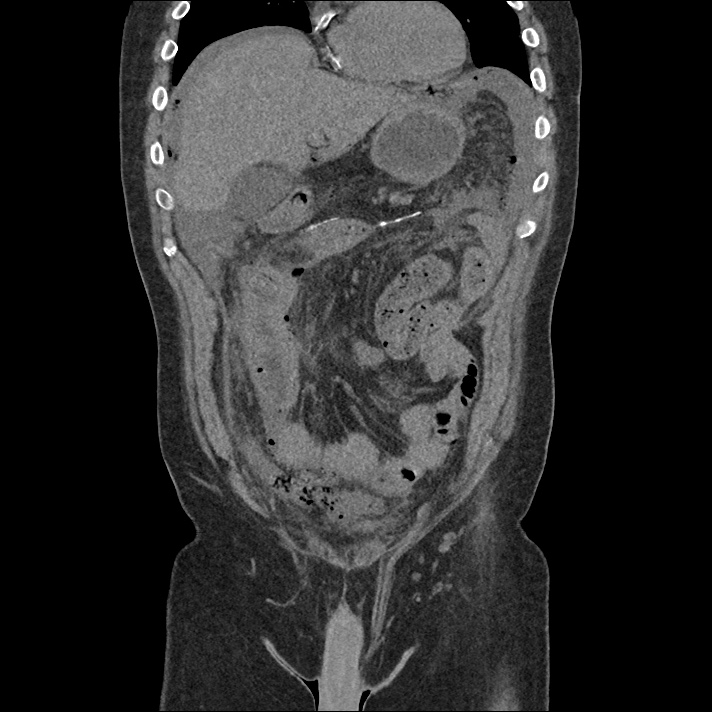

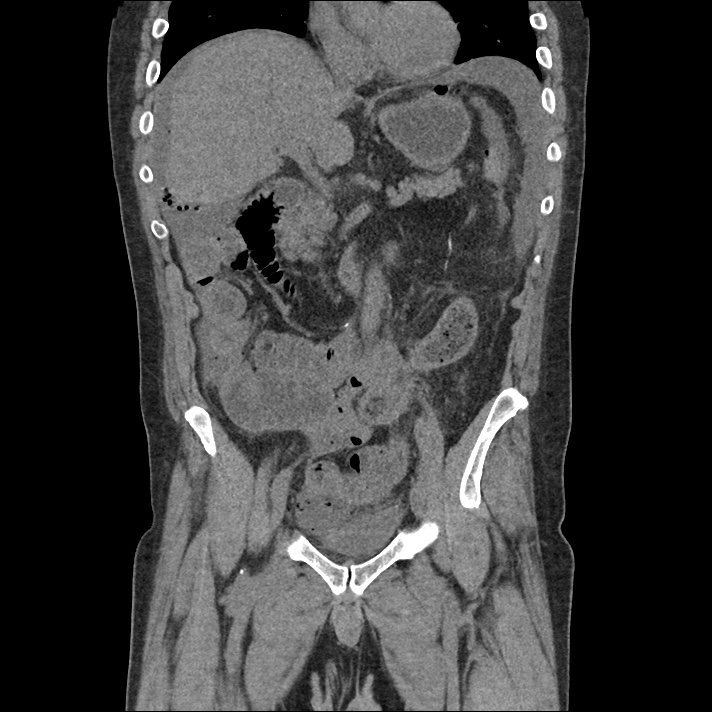

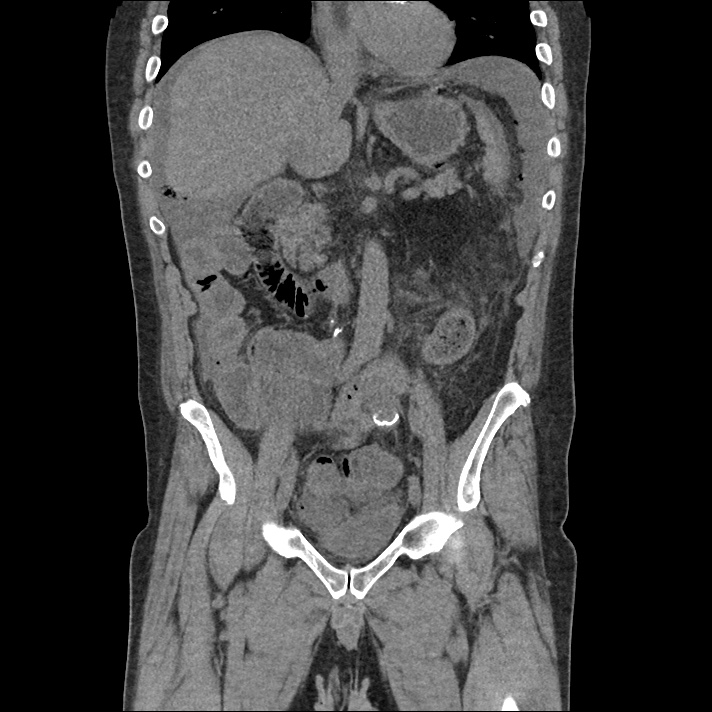

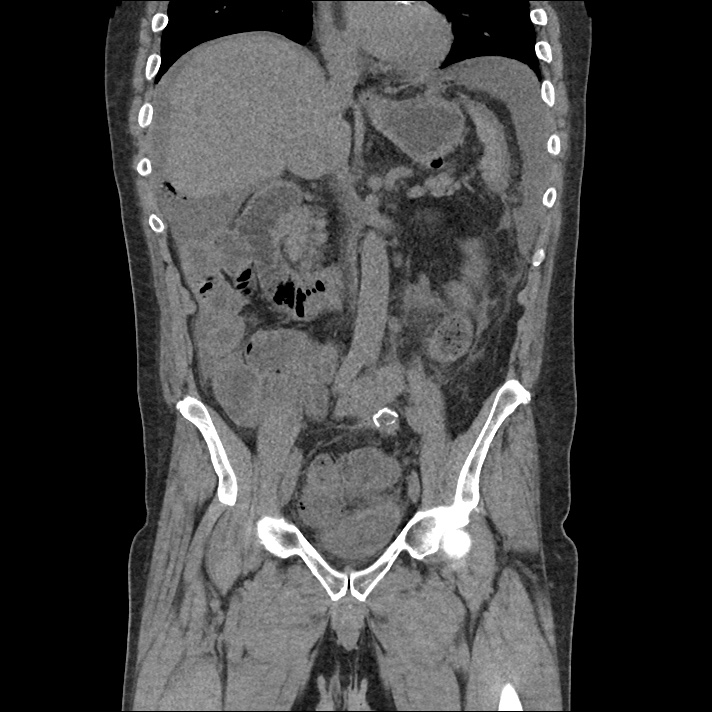

The patient was placed on supplemental oxygen, a repeat chest CT was obtained.

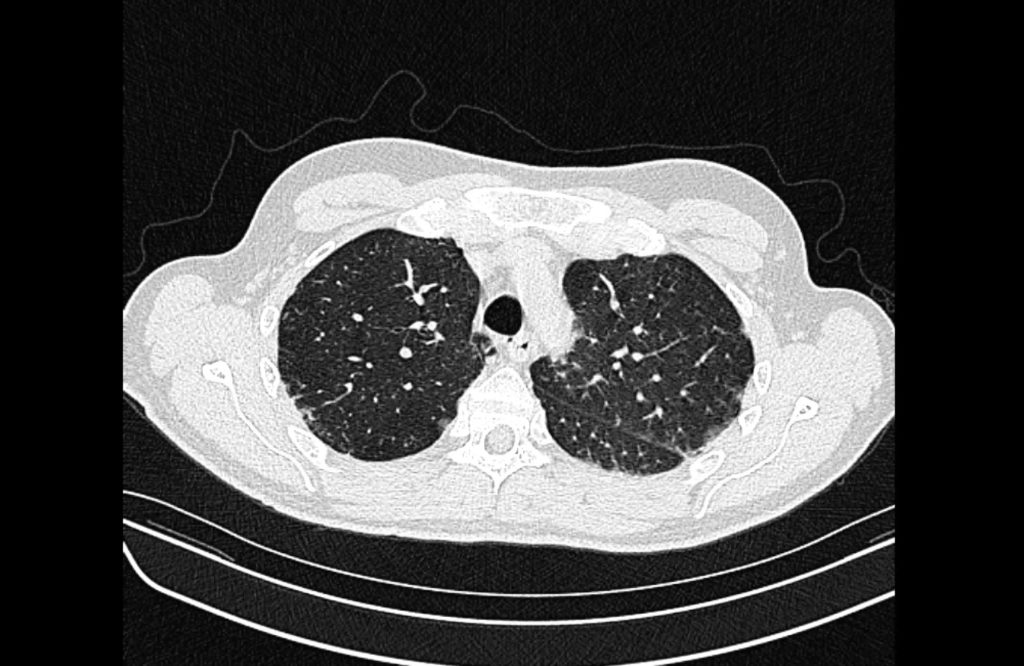

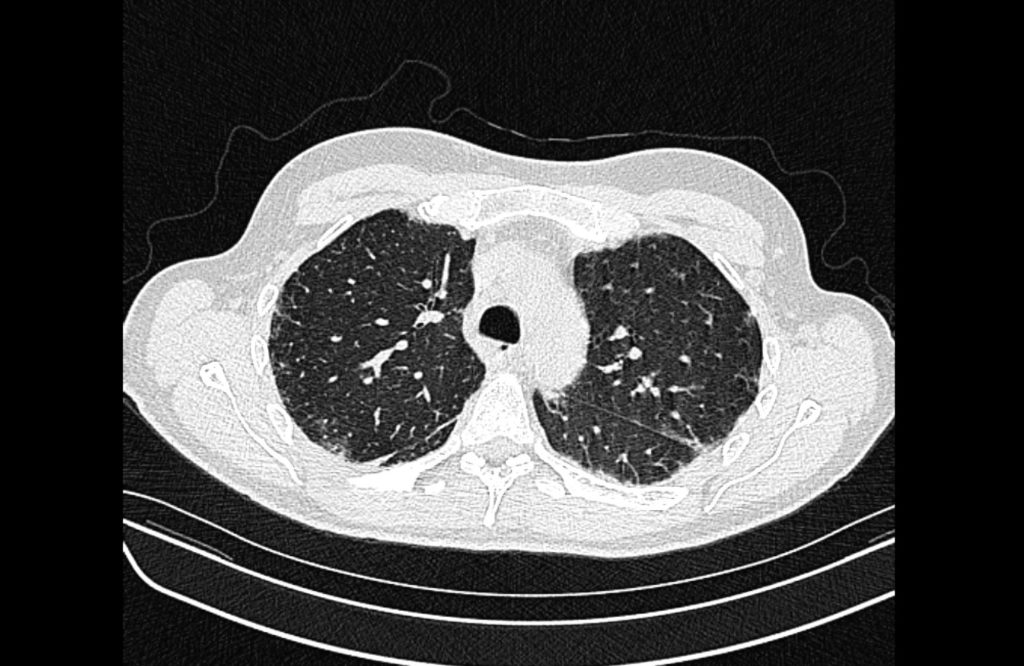

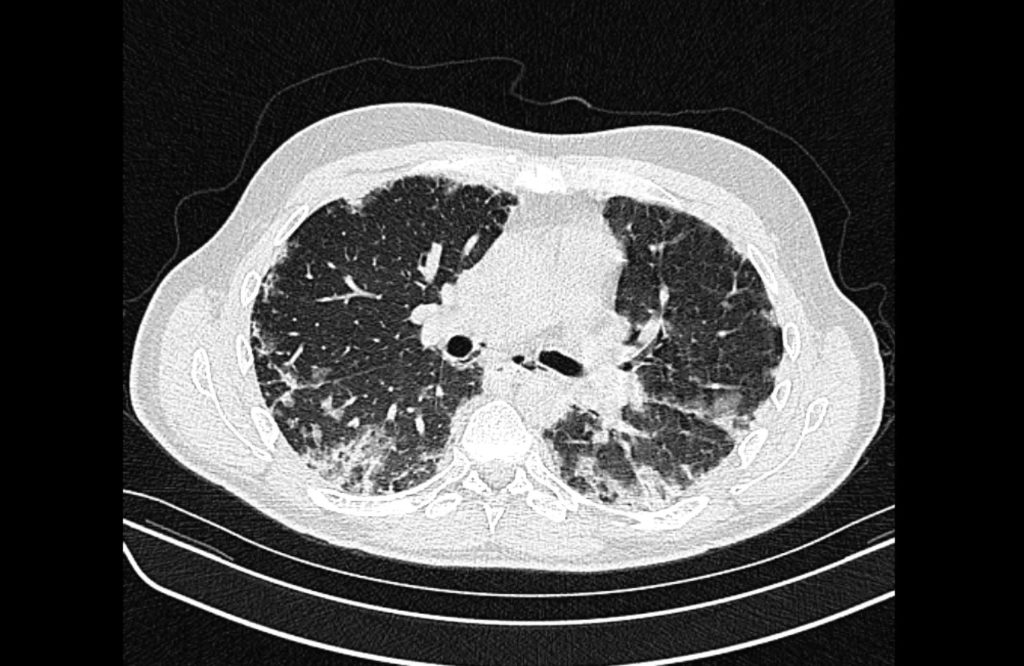

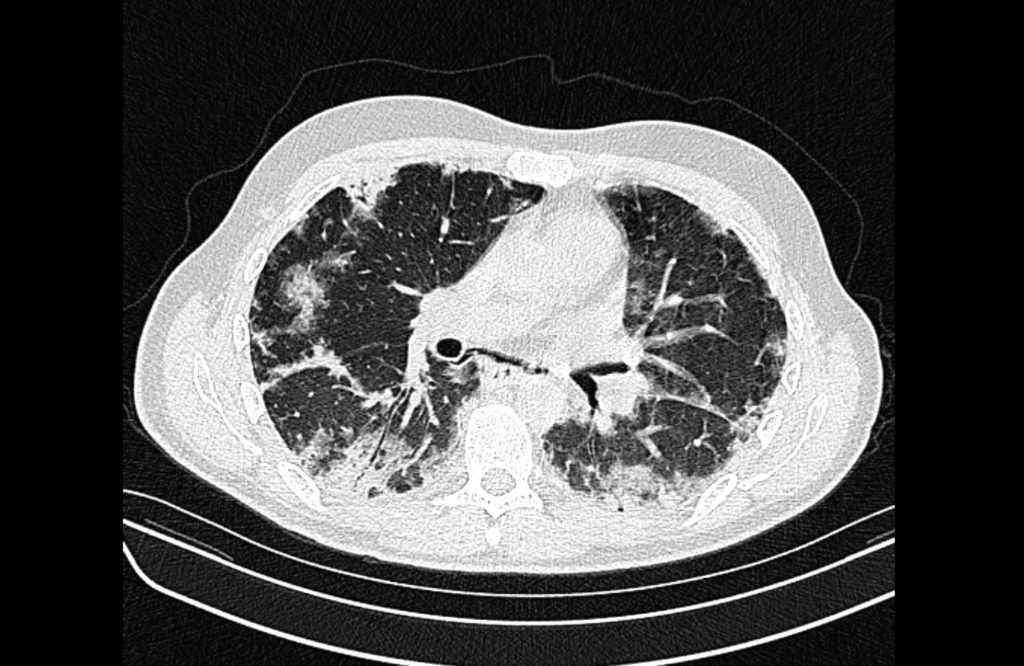

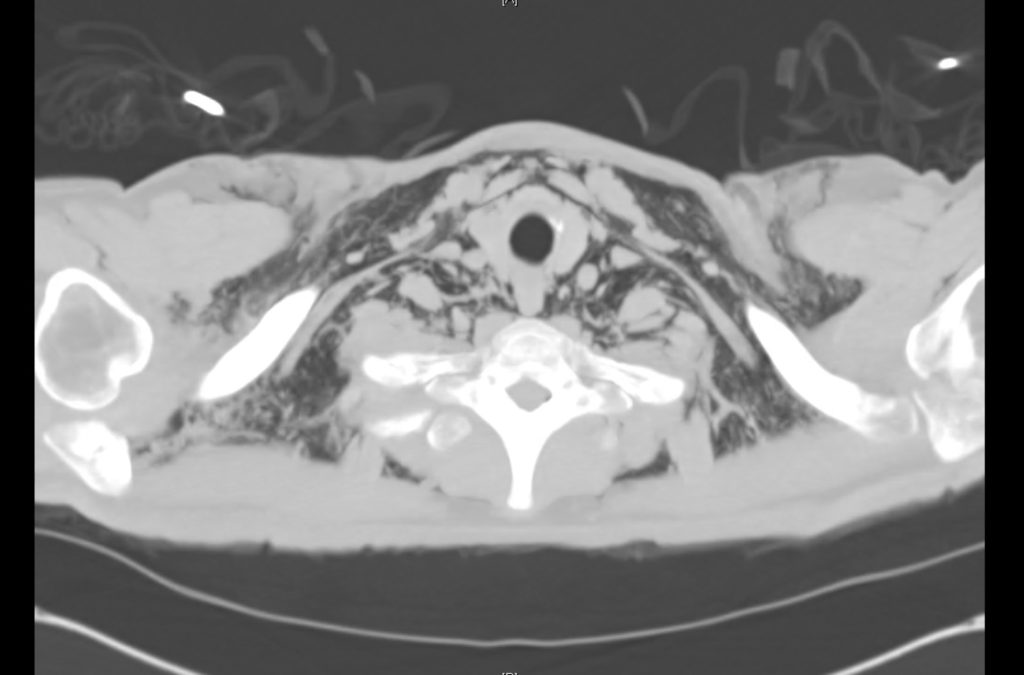

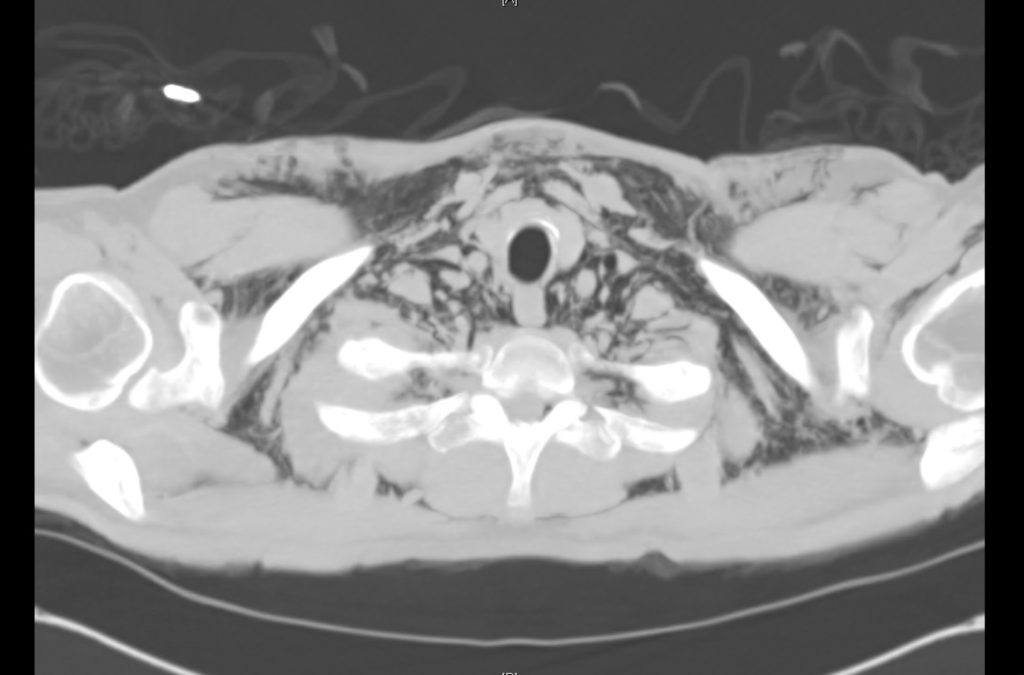

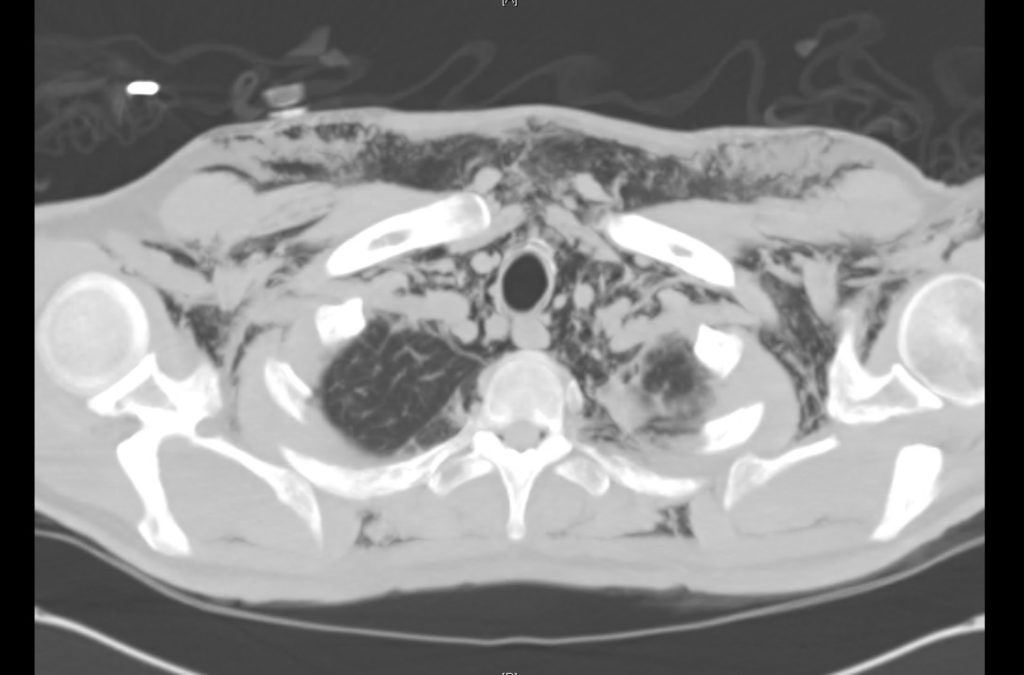

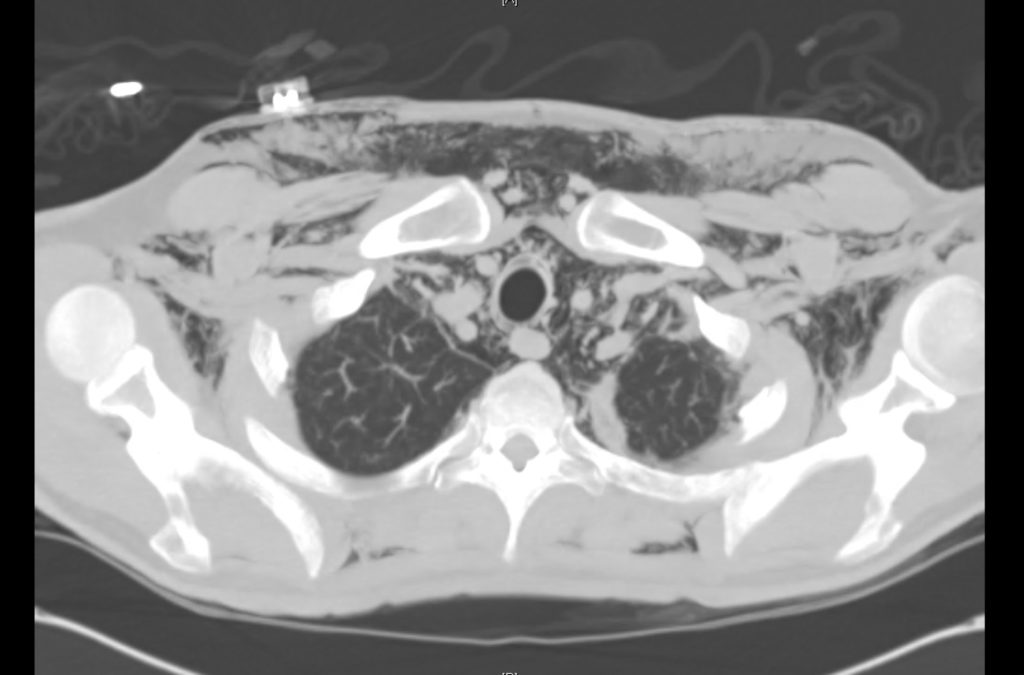

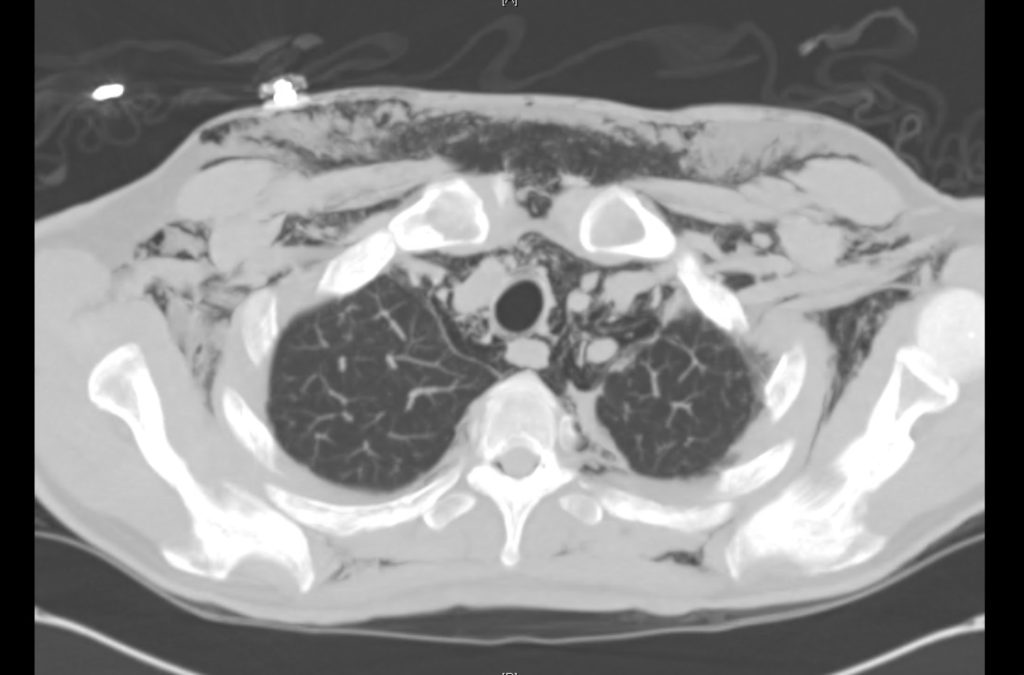

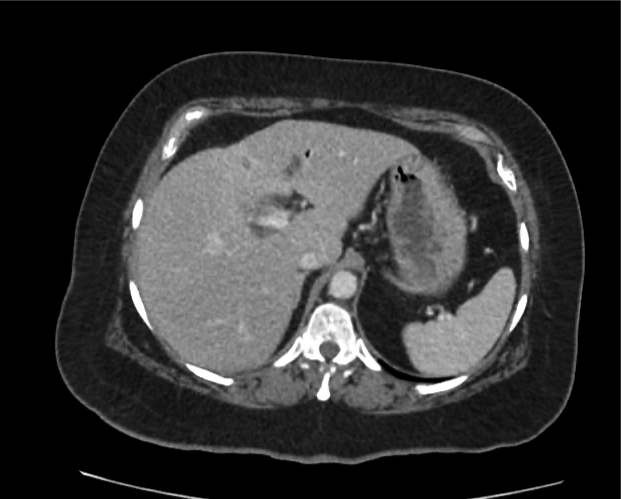

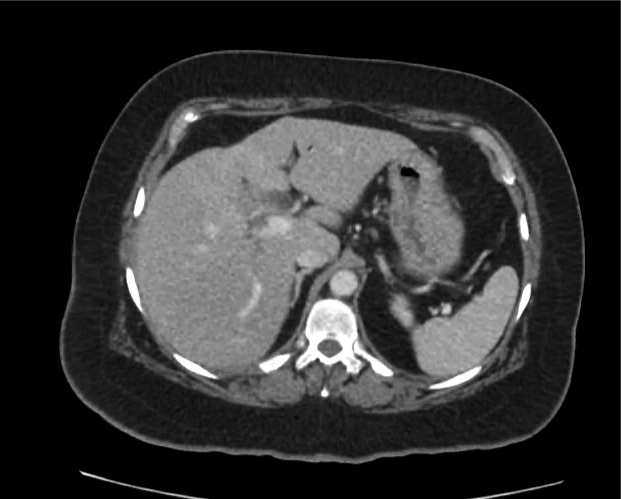

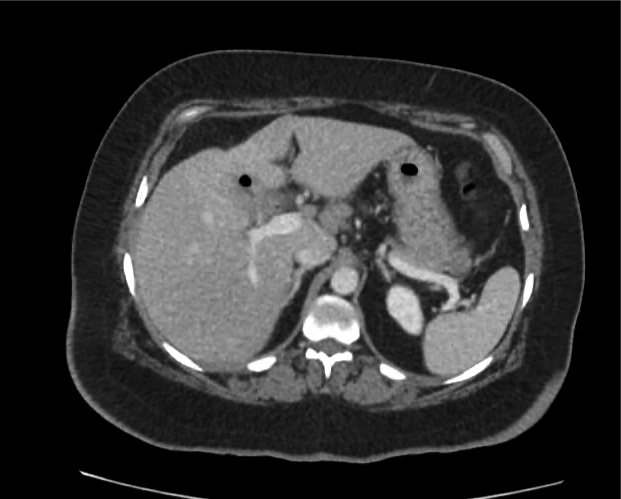

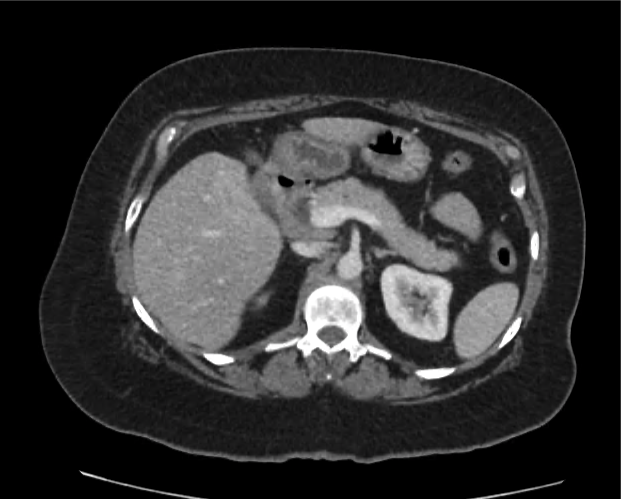

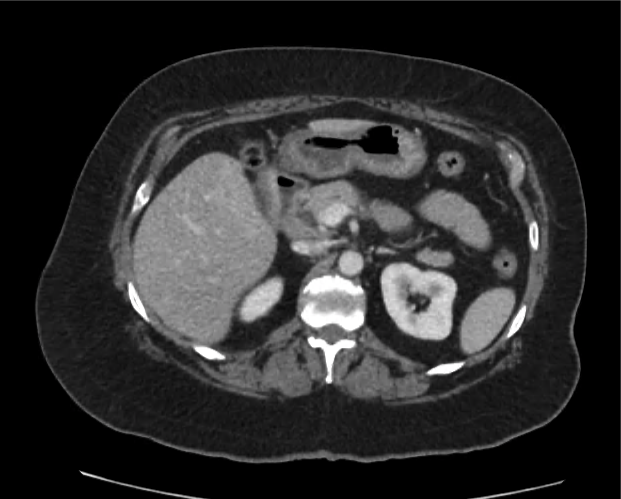

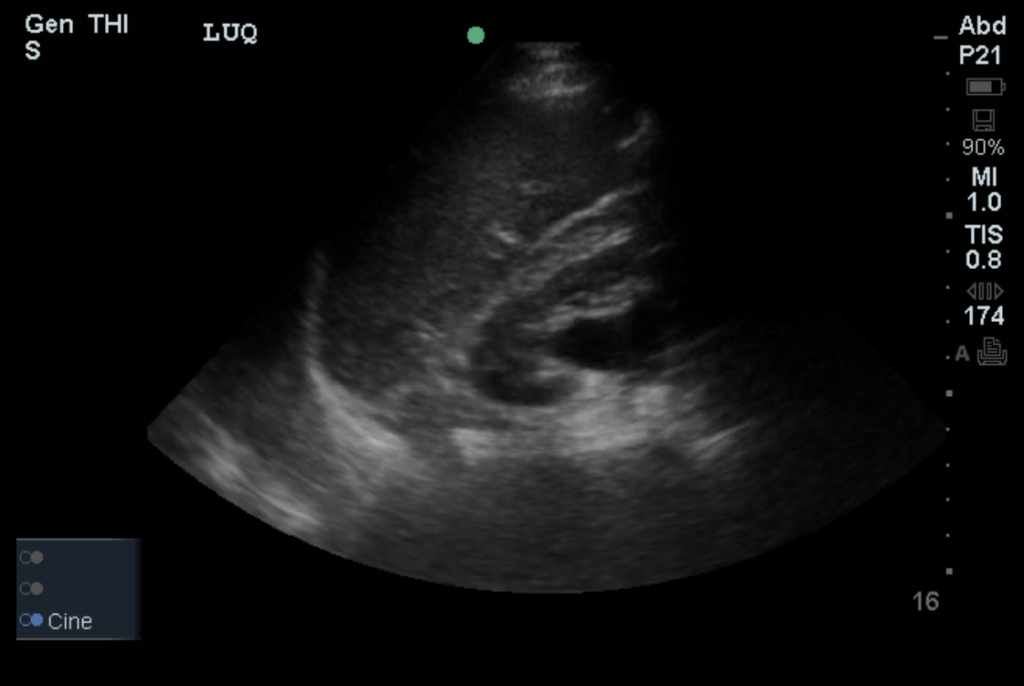

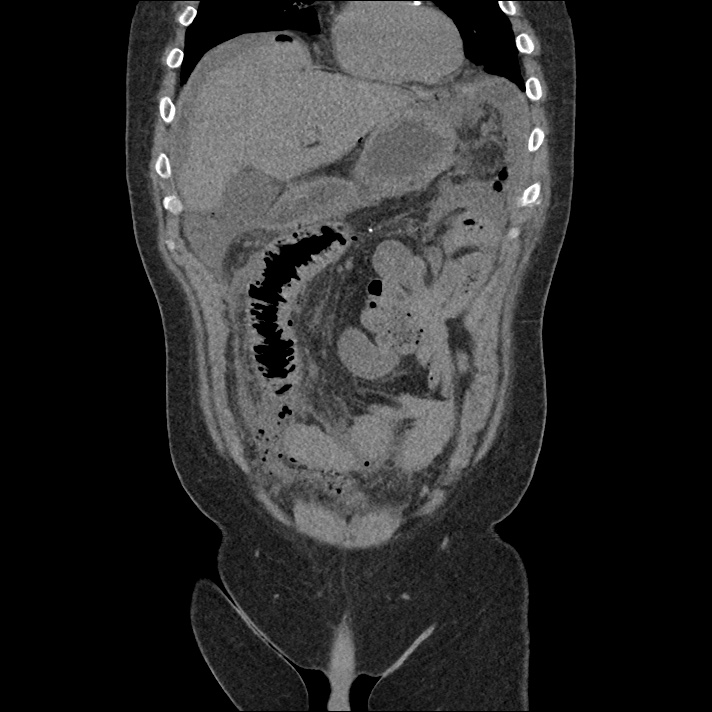

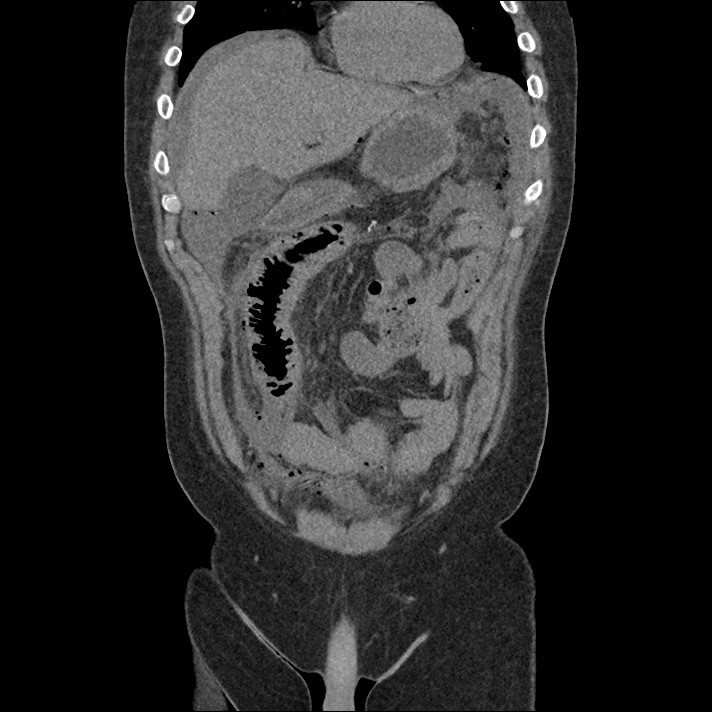

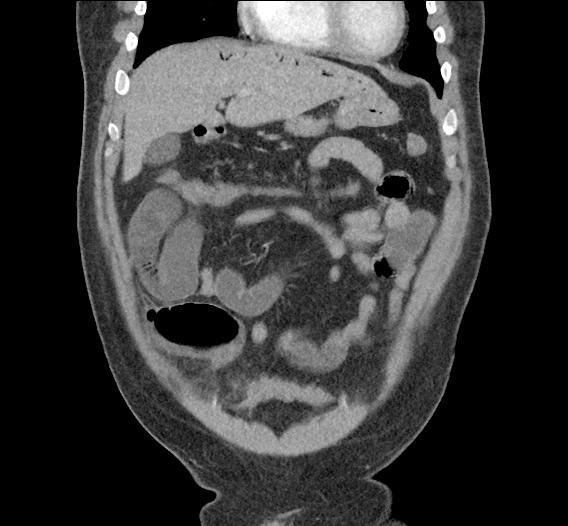

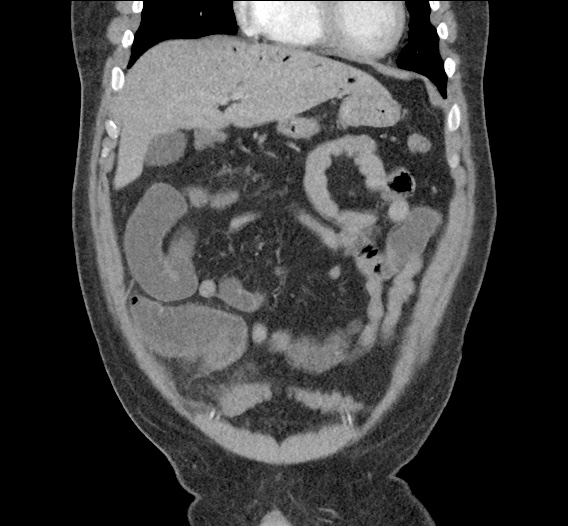

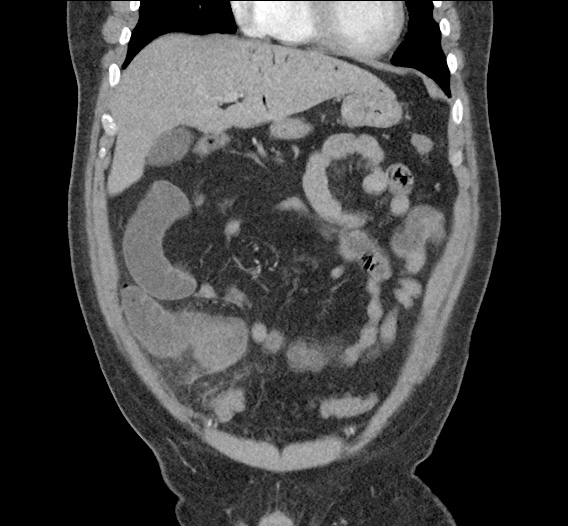

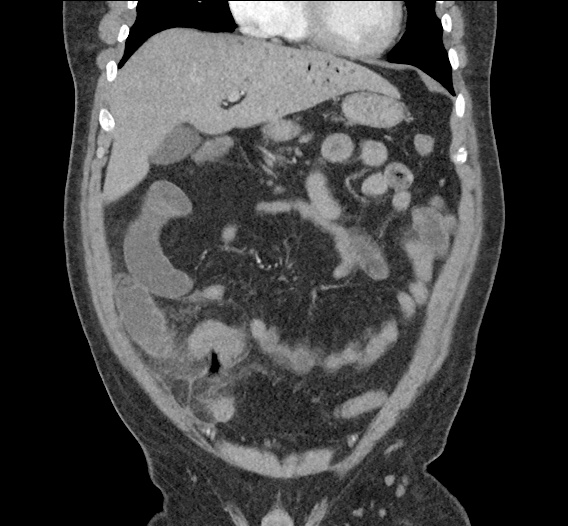

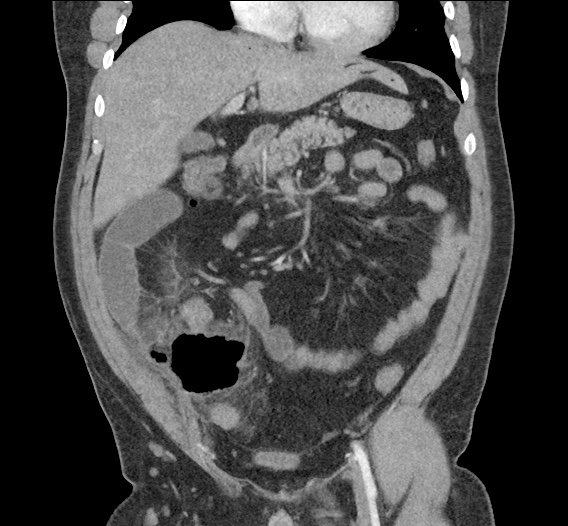

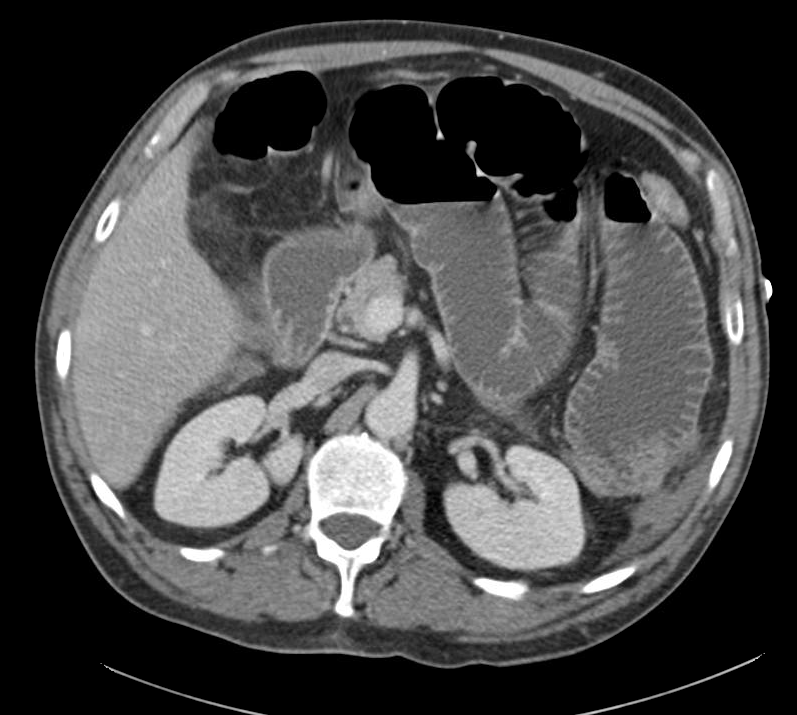

Current CT Chest:

Large pneumomediastinum extends superiorly into the bilateral lower neck and bilateral anterior and posterior chest walls. It extends inferiorly to the anterior diaphragmatic space. This most likely represents spontaneous pneumomediastinum in the clinical setting of interstitial lung disease. Pneumorrhachis is seen, related to pneumomediastinum.

The etiology of the patient’s spontaneous pneumomediastinum was deemed to be related to his underlying interstitial lung disease provoked by viral respiratory tract infection related coughing. He was observed for two days without decompensation and was discharged with outpatient follow-up.

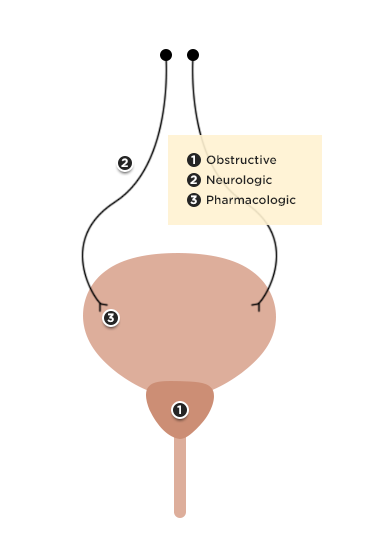

Pathophysiology of Pneumomediastinum

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum results from the rupture of terminal alveoli with subsequent tracking of gas along the bronchovascular tree through interstitial lung tissue to the mediastinum and adjacent structures (pleural, pericardial, retropharyngeal, retroperitoneal, intraperitoneal and subcutaneous spaces)1.

Secondary pneumomediastinum arises from non-alveolar sources including the gastrointestinal tract (most gravely, esophageal rupture though also from other intraperitoneal sources2), and upper respiratory tract (including facial fractures3).

Management of Pneumomediastinum5-7

The management of spontaneous pneumomediastinum focuses on treatment of the underlying precipitant, supportive care, administration of supplemental oxygen (to promote gas reabsorption) and observation for complications including rare progression to tension pneumomediastinum4.

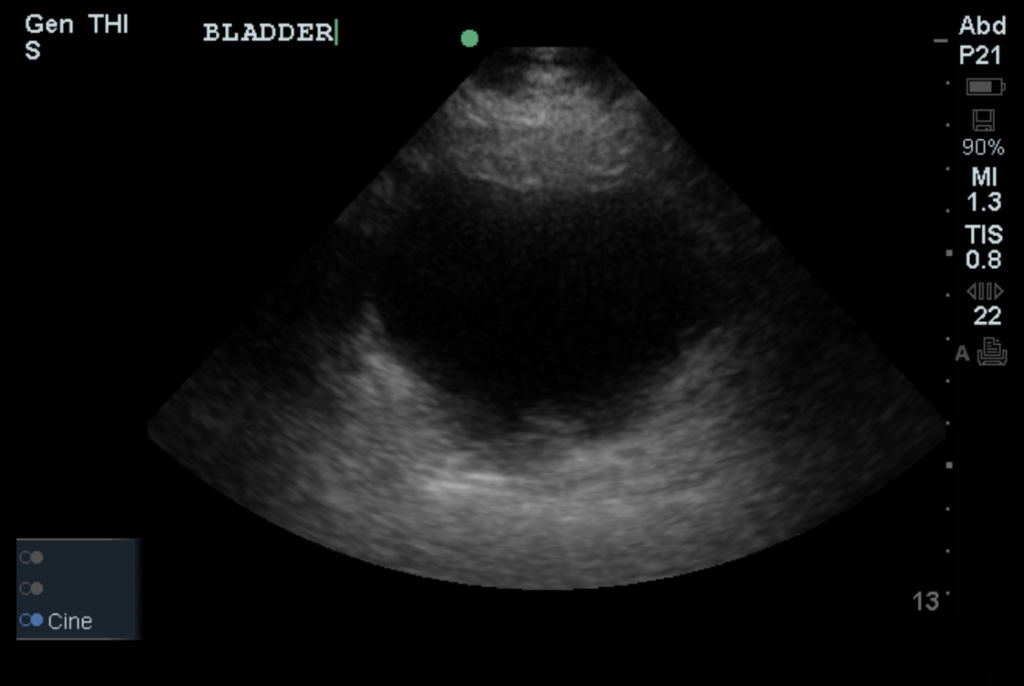

Secondary pneumomediastinum is of significantly more concern and should be suspected in patients with any of the following features:

Symptoms

- History of forceful vomiting

- Dysphagia

Signs

- Fever

- Hemodynamic instability

- Left-sided pleural effusion

- Abdominal tenderness

- Leukocytosis

Management is aggressive including resuscitation, maintenance of NPO status, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and emergent surgical consultation.

Differential Diagnosis of Pneumomediastinum5-11

References:

- Macklin, M., Macklin, C. (1944). Malignant Interstitial Emphysema of the Lungs and Mediastinum as an Important Occult Complication in Many Respiratory Diseases and Other Conditions: an Interpretation of the Clinical Literature in the Light of Laboratory Experiment Medicine 23(4)

- Fosi, S., Giuricin, V., Girardi, V., Caprera, E., Costanzo, E., Trapano, R., Simonetti, G. (2014). Subcutaneous Emphysema, Pneumomediastinum, Pneumoretroperitoneum, and Pneumoscrotum: Unusual Complications of Acute Perforated Diverticulitis Case Reports in Radiology 2014(), 1-5. https://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/431563

- Luca, G., Petteruti, F., Tanga, M., Luciano, A., Lerro, A. (2011). Pneumomediastinum and Subcutaneous Emphysema Unusual Complications of Blunt Facial Trauma Indian Journal of Surgery 73(5), 380-381. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12262-011-0310-x

- Shennib, H., Barkun, A., Matouk, E., Blundell, P. (1988). Surgical Decompression of a Tension Pneumomediastinum Chest 93(6), 1301-1302. https://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.93.6.1301

- Bakhos, C., Pupovac, S., Ata, A., Fantauzzi, J., Fabian, T. (2014). Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: an extensive workup is not required. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 219(4), 713-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.06.001

- Iyer, V., Joshi, A., Ryu, J. (2009). Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum: Analysis of 62 Consecutive Adult Patients Mayo Clinic Proceedings 84(5), 417-421. https://dx.doi.org/10.4065/84.5.417

- Takada, K., Matsumoto, S., Hiramatsu, T., Kojima, E., Shizu, M., Okachi, S., Ninomiya, K., Morioka, H. (2009). Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: an algorithm for diagnosis and management. Therapeutic advances in respiratory disease 3(6), 301-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1753465809350888

- Al-Mufarrej, F., Badar, J., Gharagozloo, F., Tempesta, B., Strother, E., Margolis, M. (2008). Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. Journal of cardiothoracic surgery 3(1), 59. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1749-8090-3-59

- Takada, K., Matsumoto, S., Hiramatsu, T., Kojima, E., Watanabe, H., Sizu, M., Okachi, S., Ninomiya, K. (2008). Management of spontaneous pneumomediastinum based on clinical experience of 25 cases Respiratory Medicine 102(9), 1329-1334. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2008.03.023

- Bejvan, S., Godwin, J. (1996). Pneumomediastinum: old signs and new signs. American Journal of Roentgenology 166(5), 1041-1048. https://dx.doi.org/10.2214/ajr.166.5.8615238

- Langwieler, T., Steffani, K., Bogoevski, D., Mann, O., Izbicki, J. (2004). Spontaneous pneumomediastinum The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 78(2), 711-713. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.09.021

CC:

CC:

HPI:

HPI: