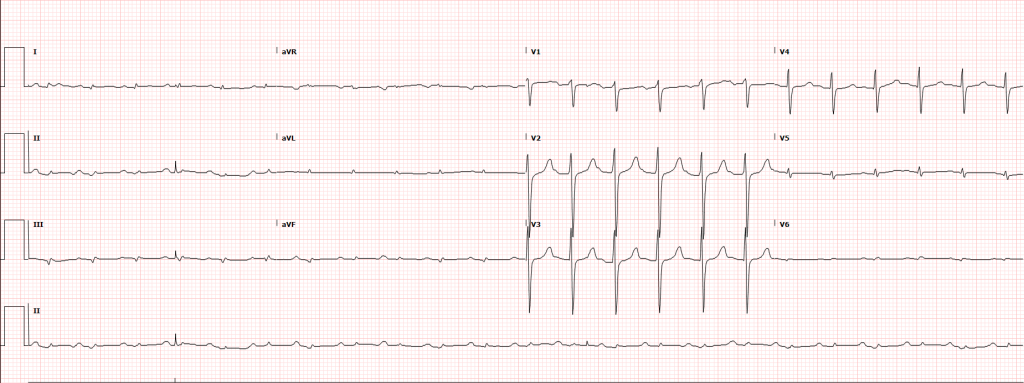

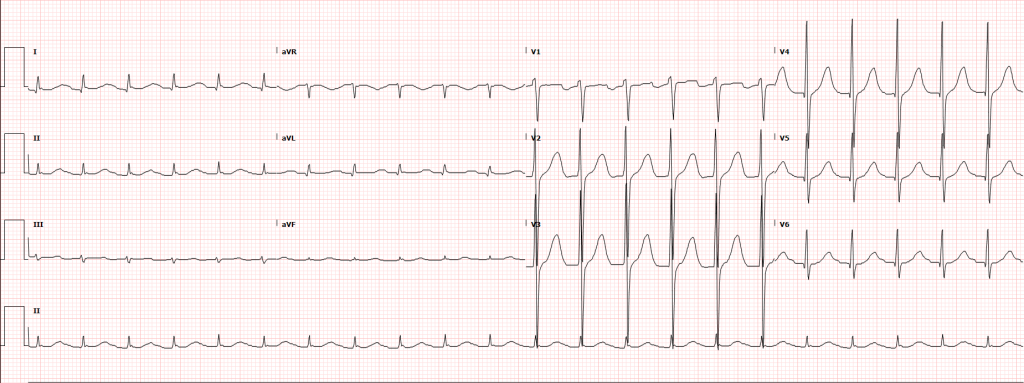

Brief HPI:

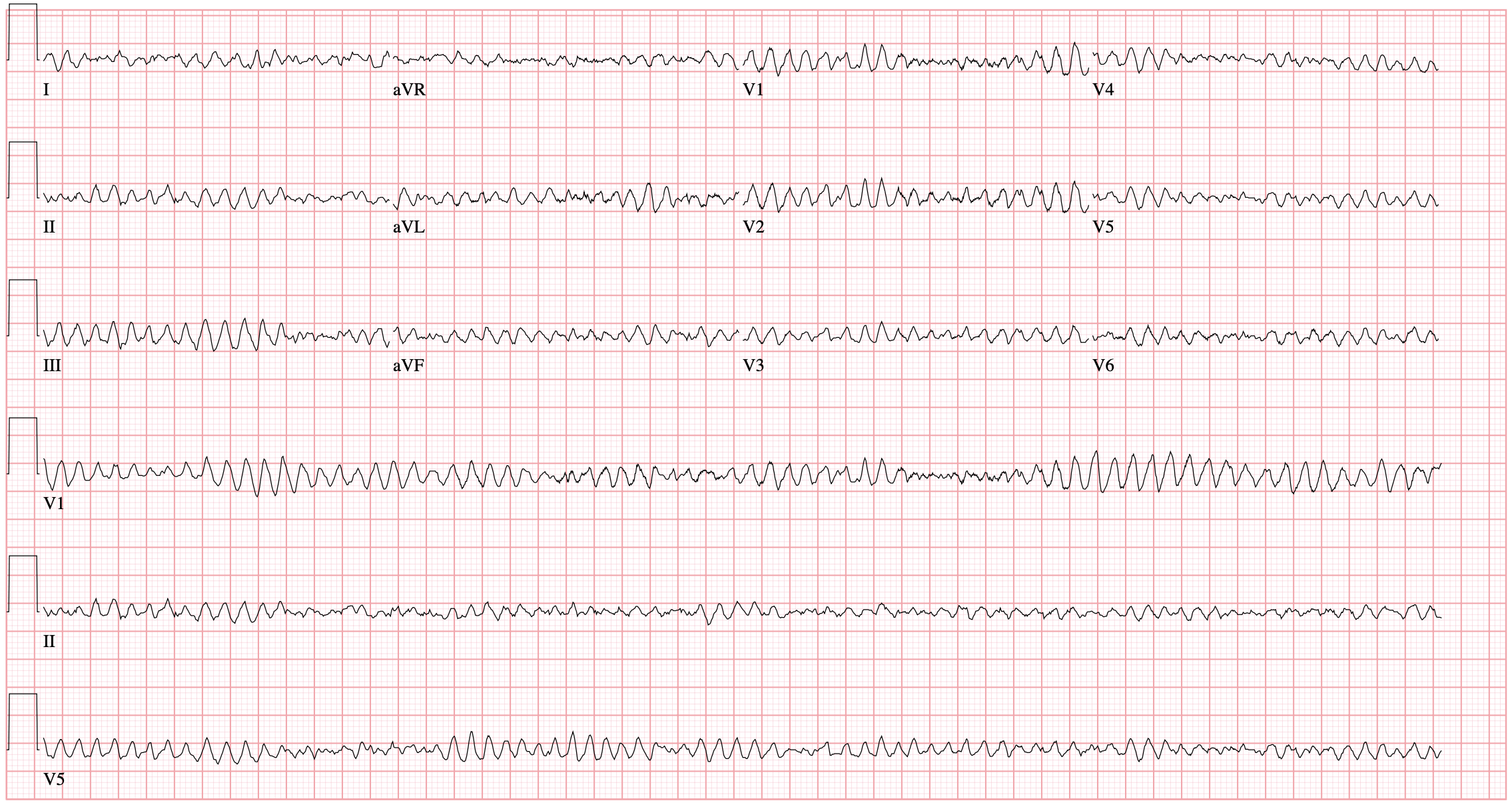

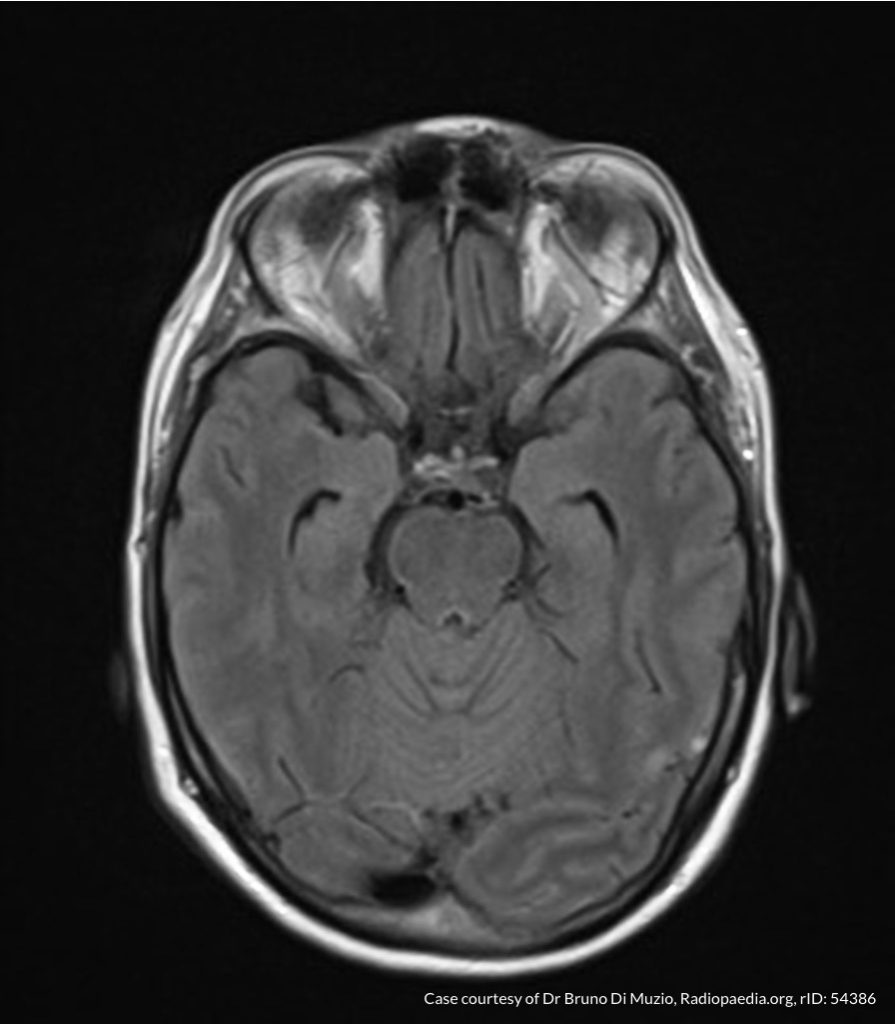

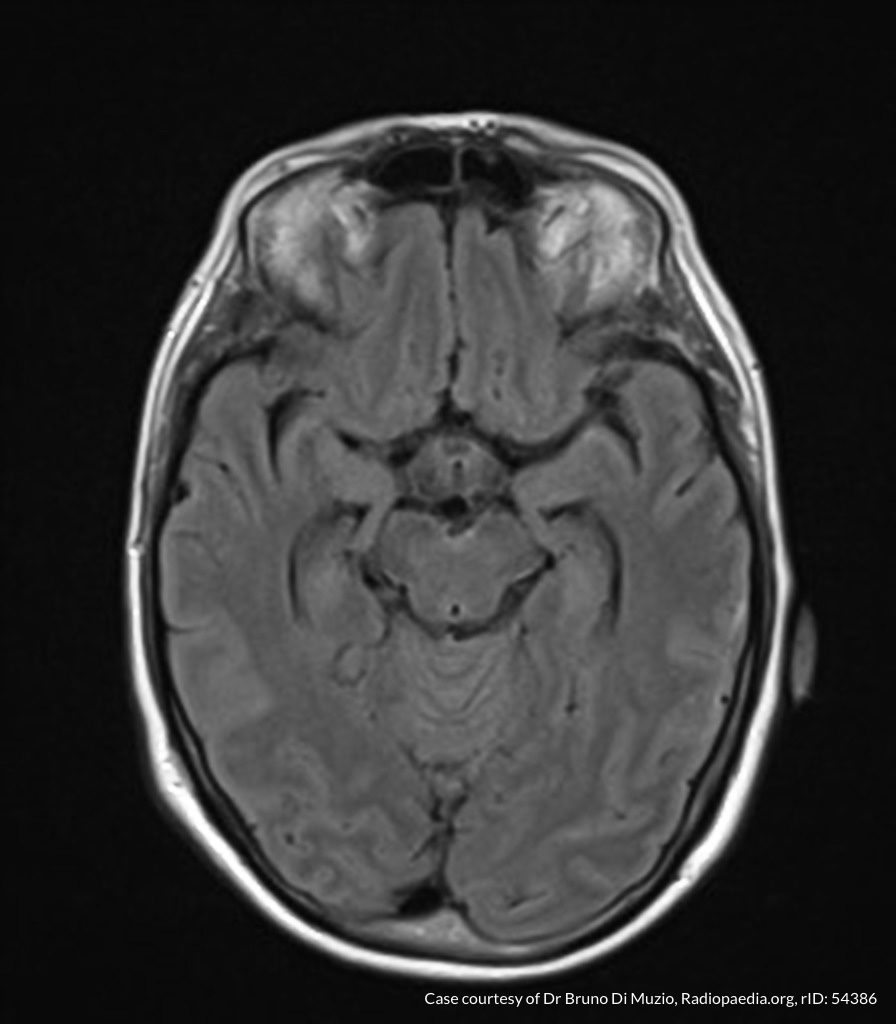

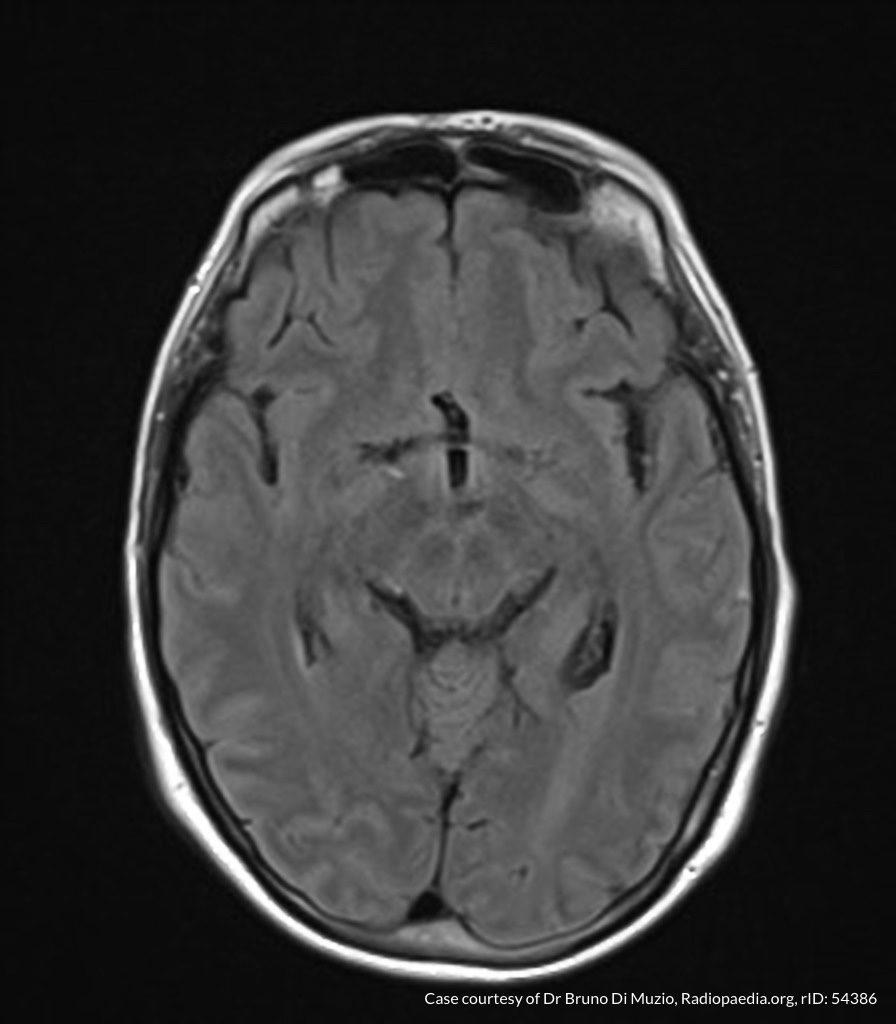

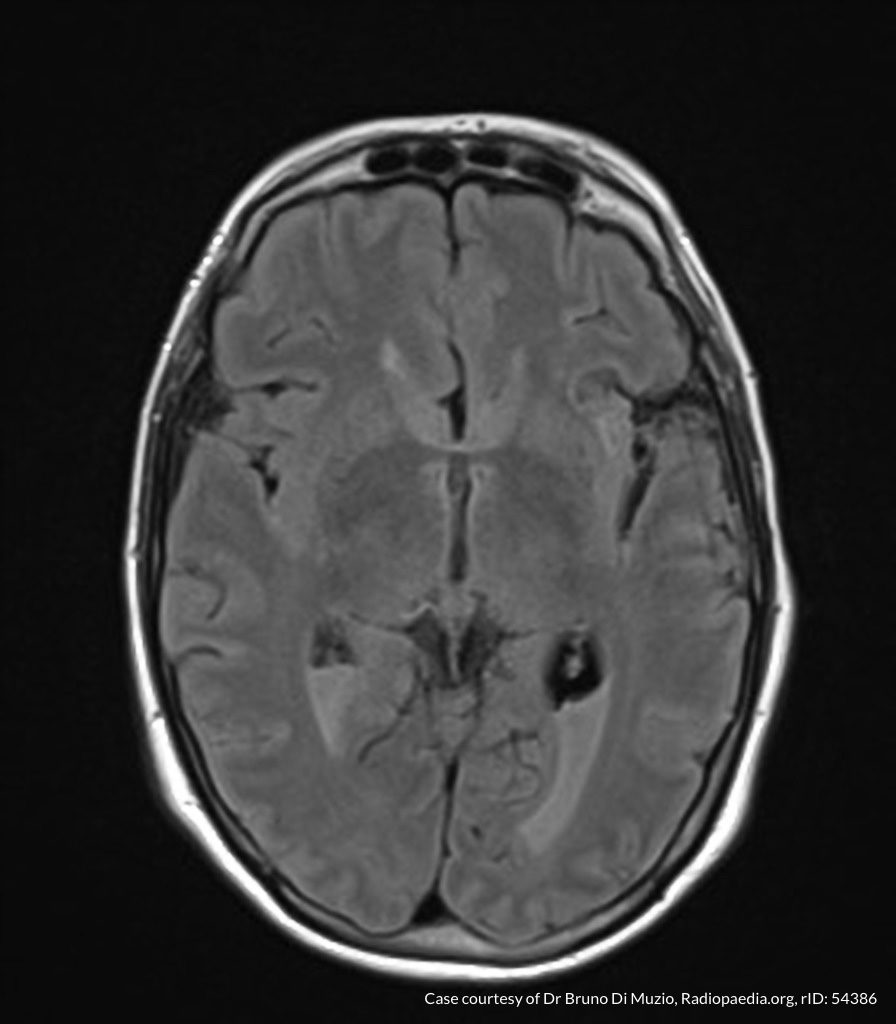

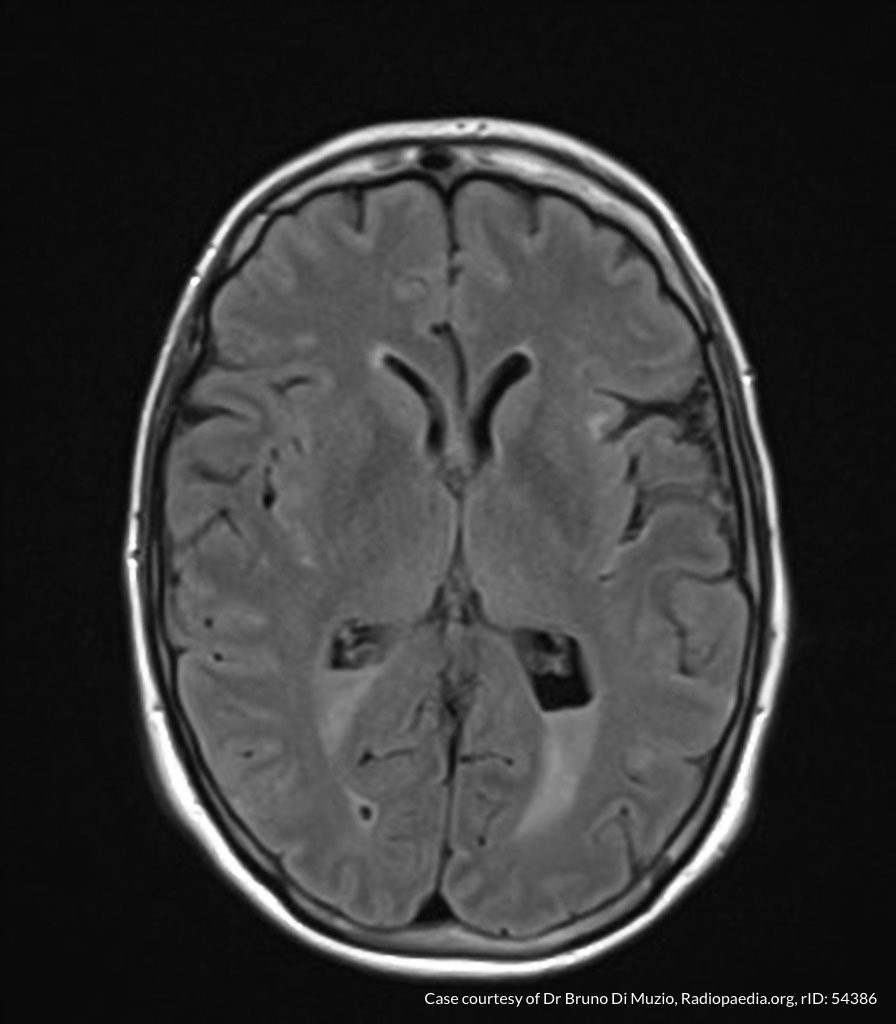

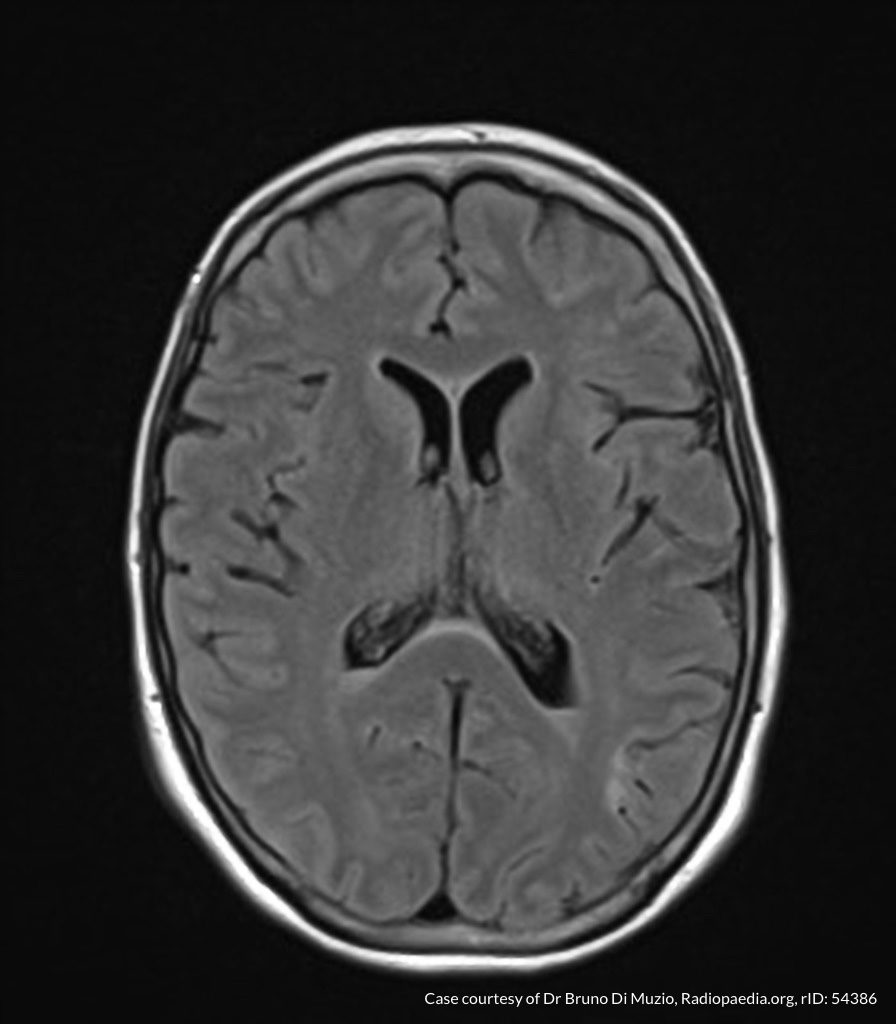

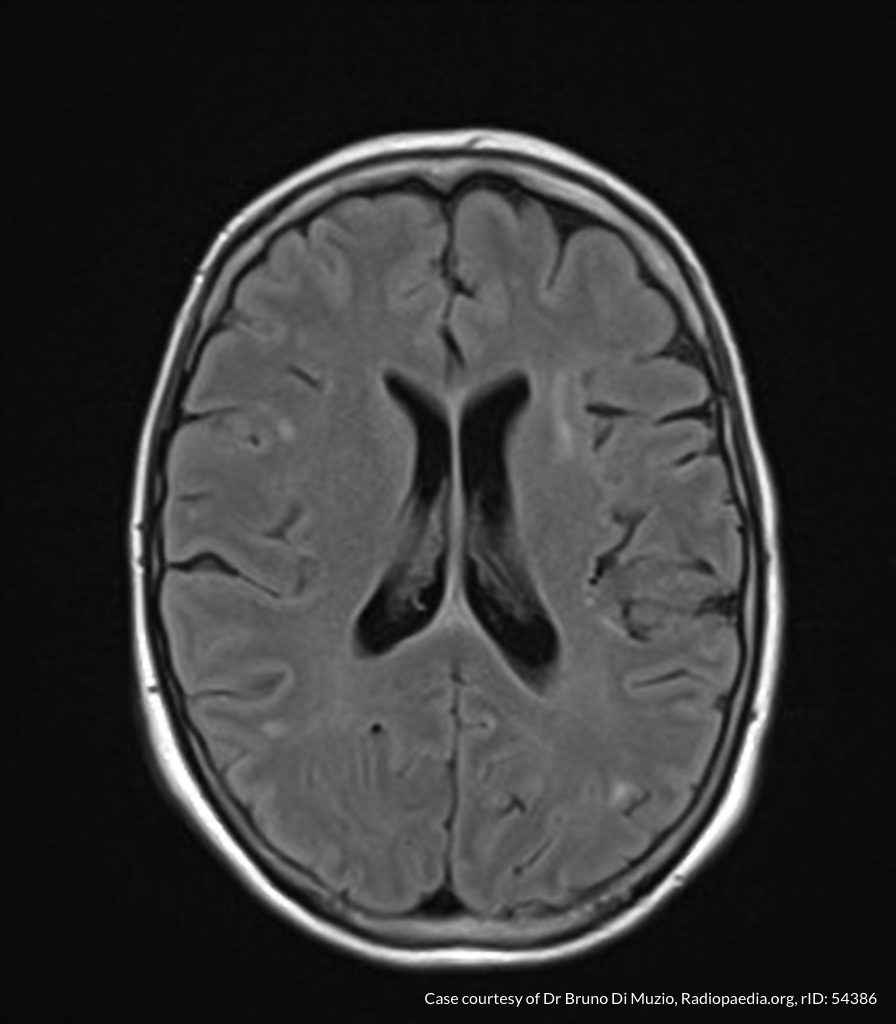

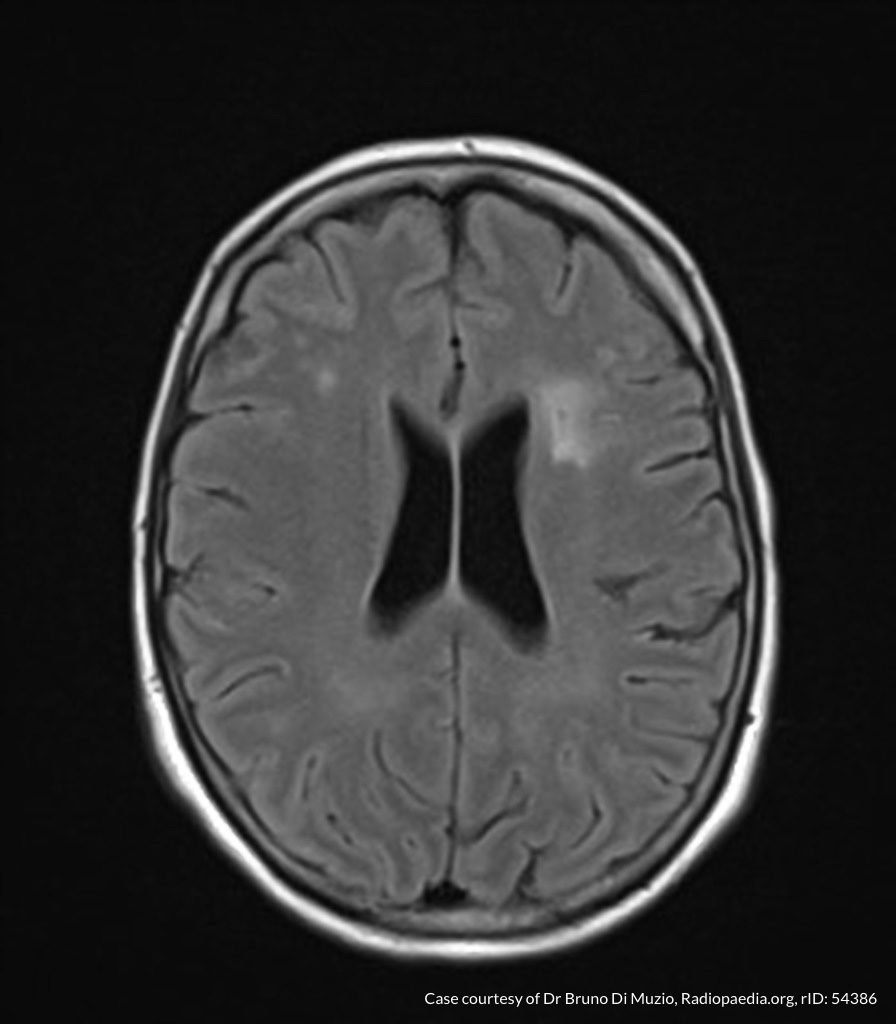

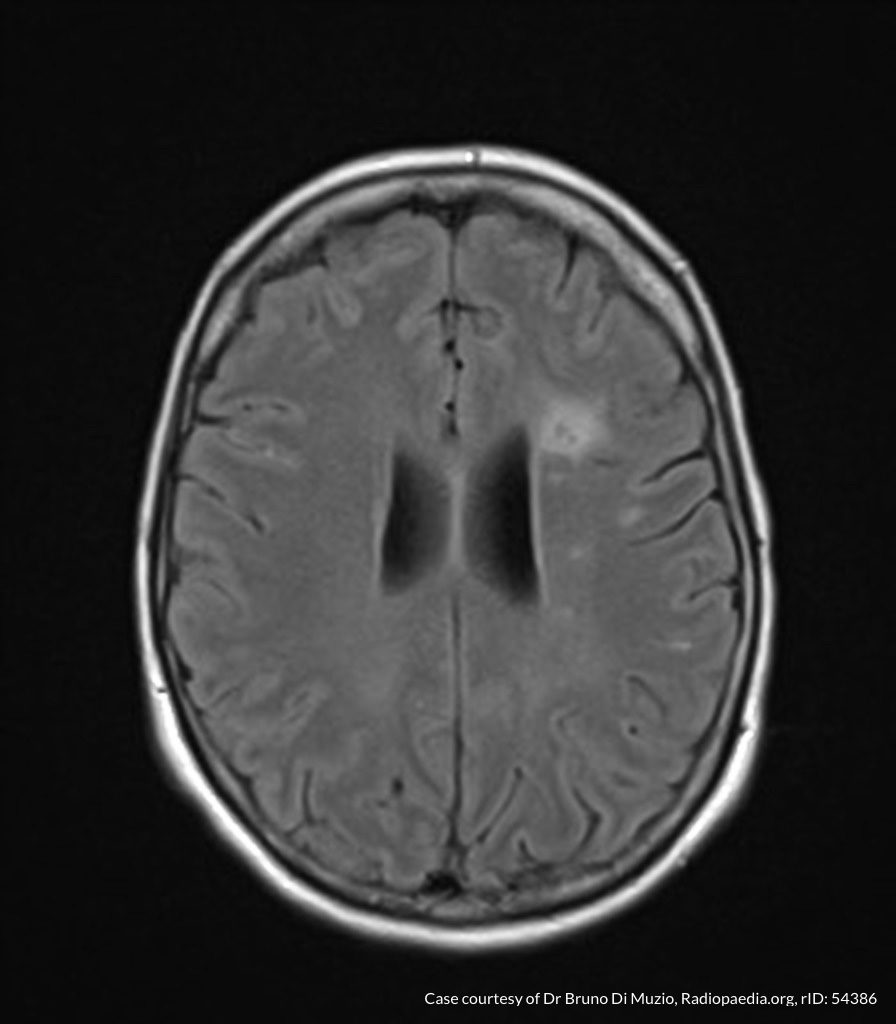

A 65-year-old male with a past medical history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and atrial fibrillation presents after a mechanical fall with a posterior scalp hematoma and altered mental status. The patient’s family reports that the patient is taking apixaban with his last dose 4 hours prior to arrival. Physical examination reveals a GCS of 13, blood pressure of 175/99, and asymmetric pupils. The patient is taken to CT where head imaging reveals left sided subdural hematoma with midline shift and developing uncal herniation.

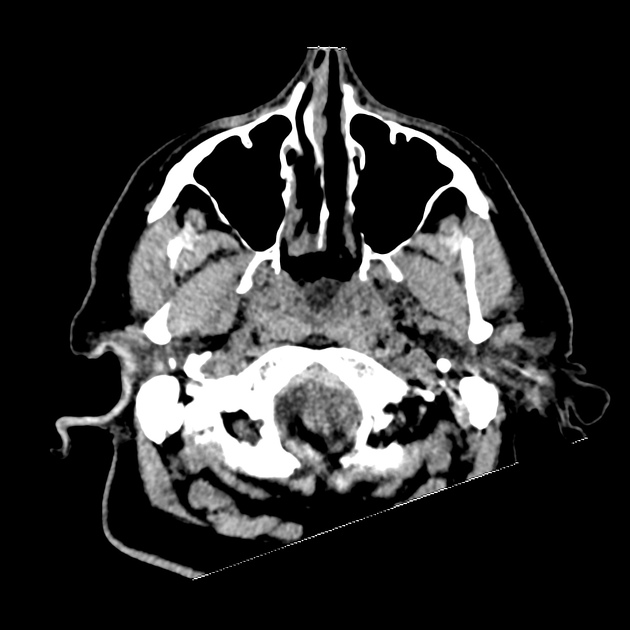

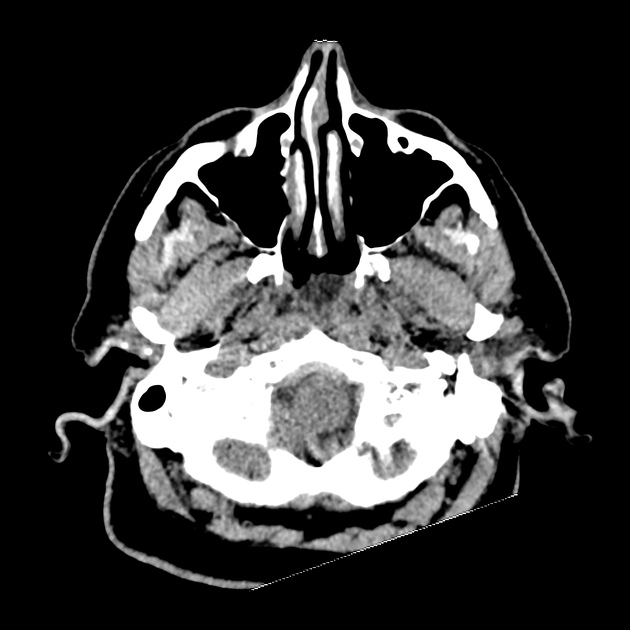

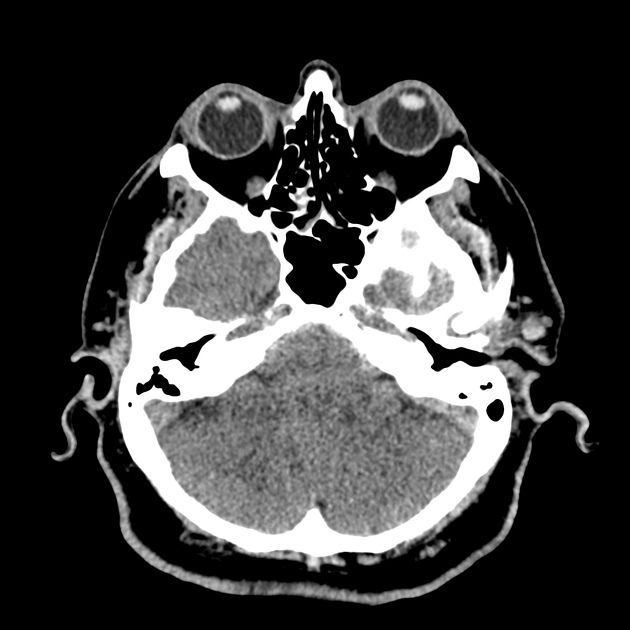

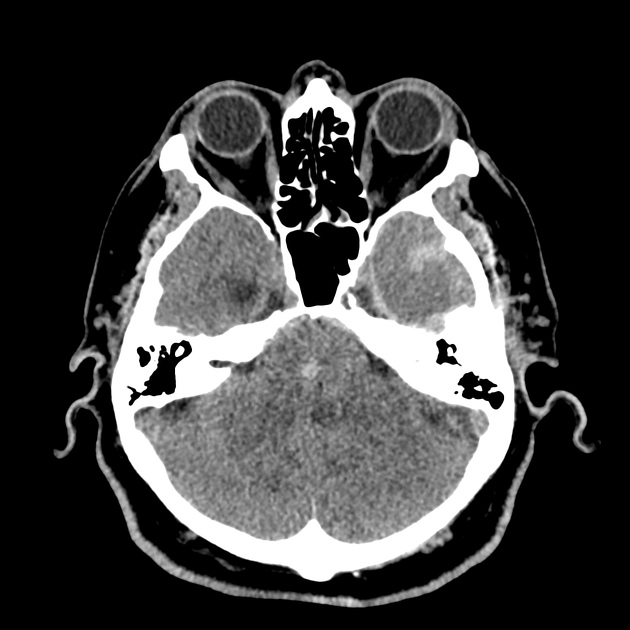

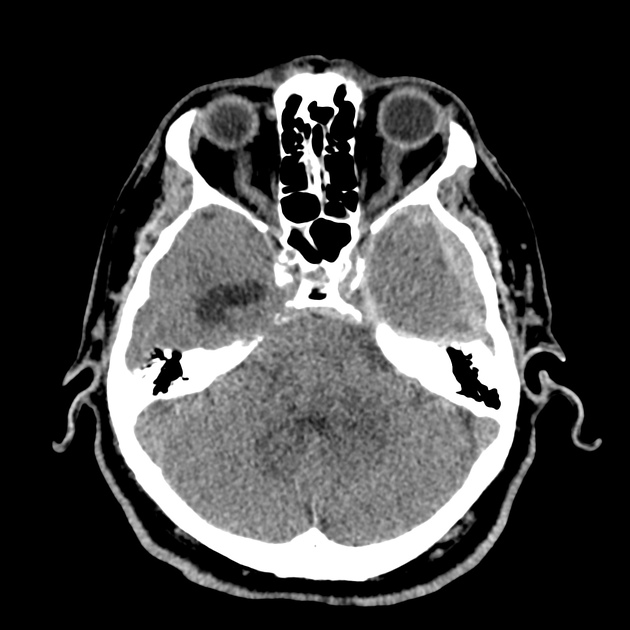

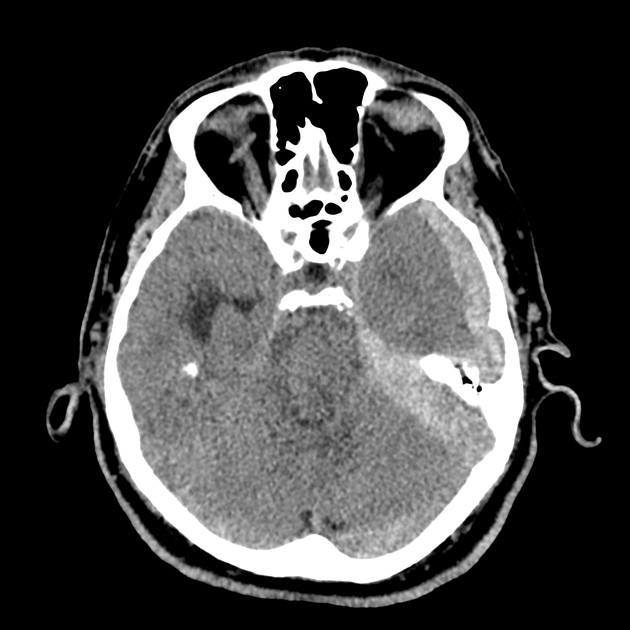

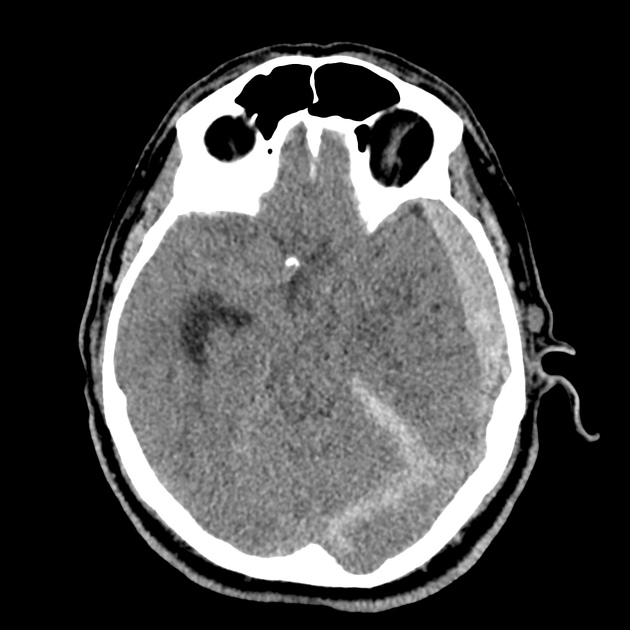

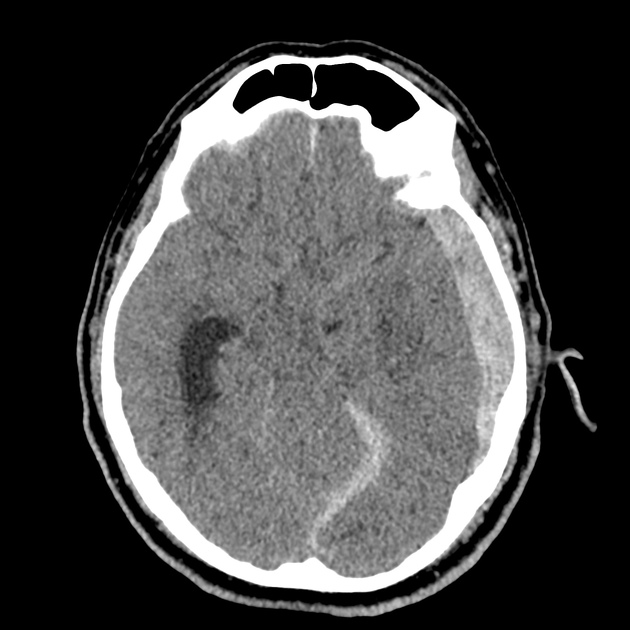

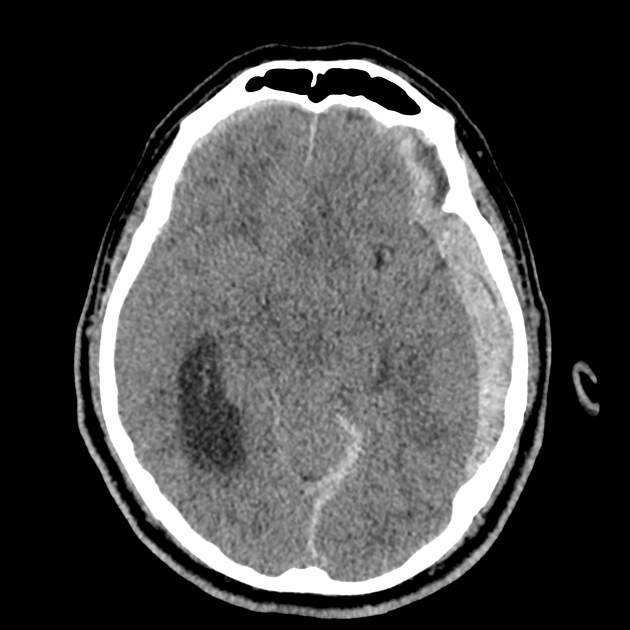

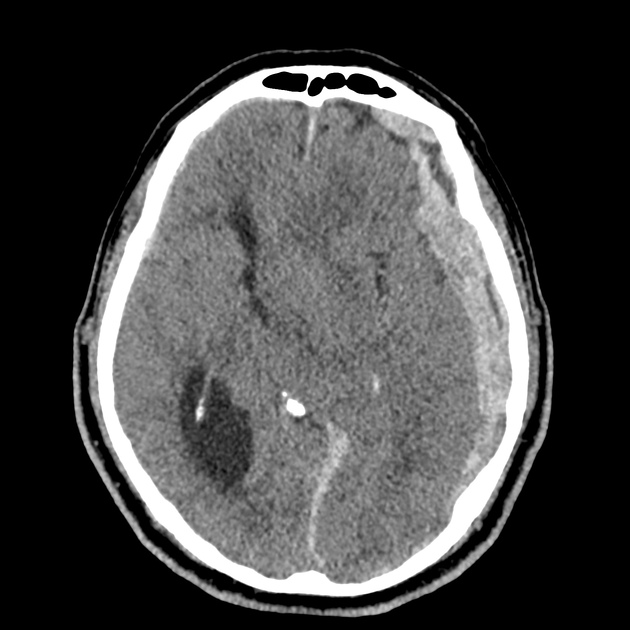

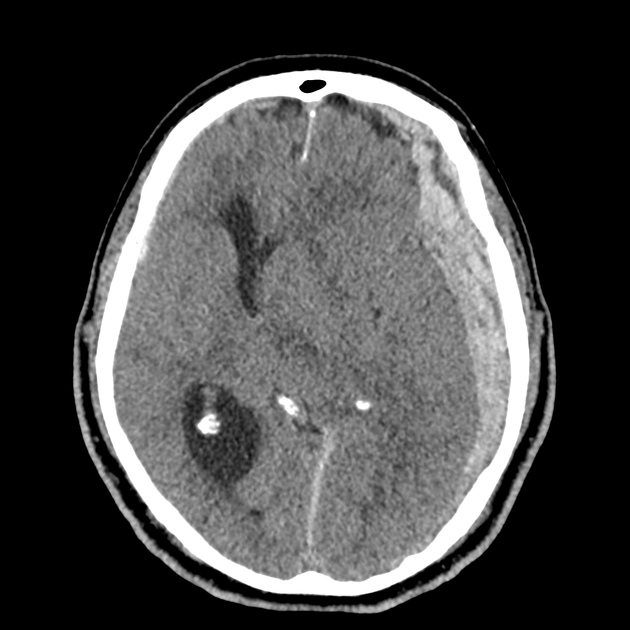

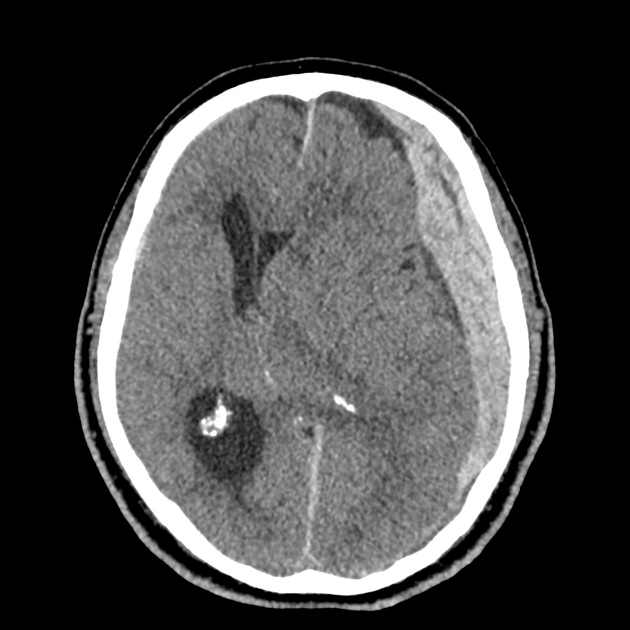

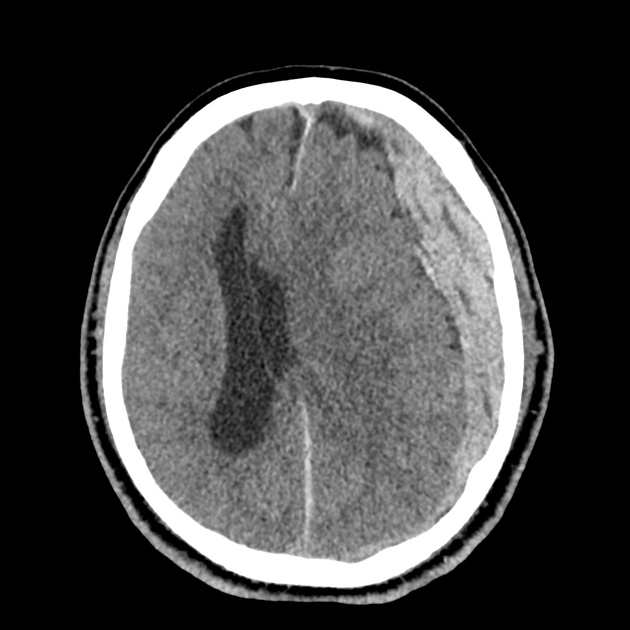

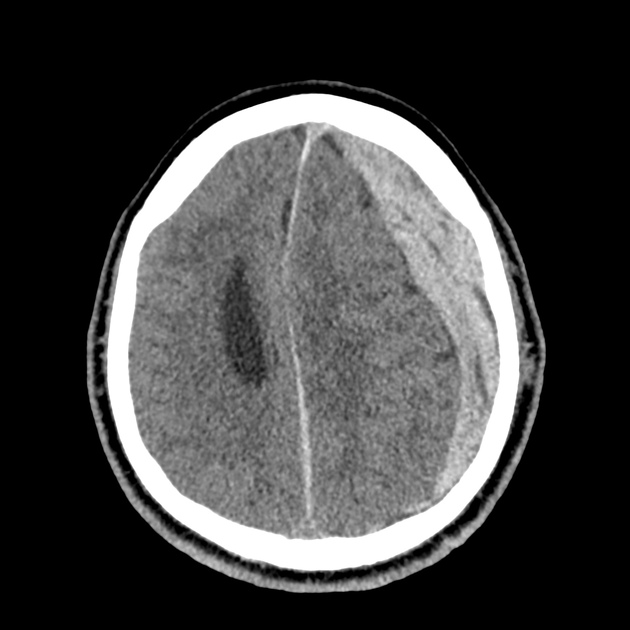

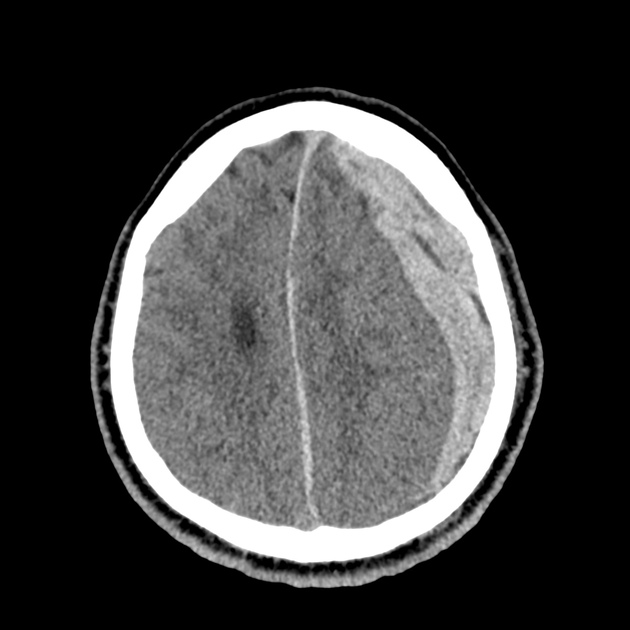

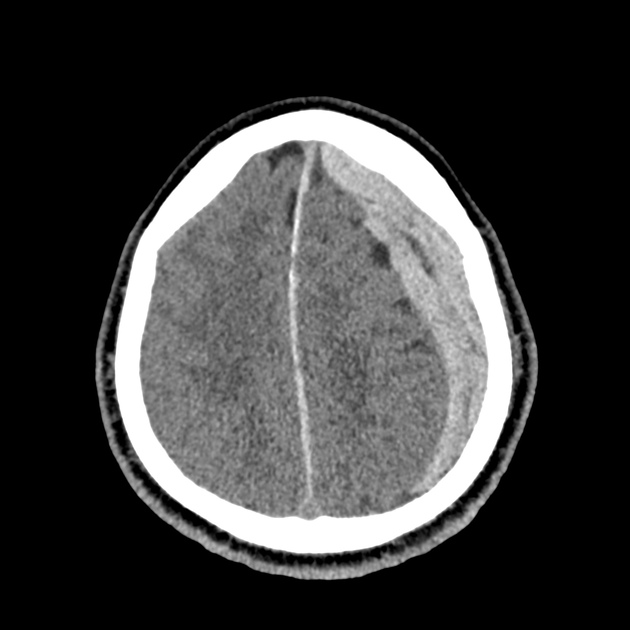

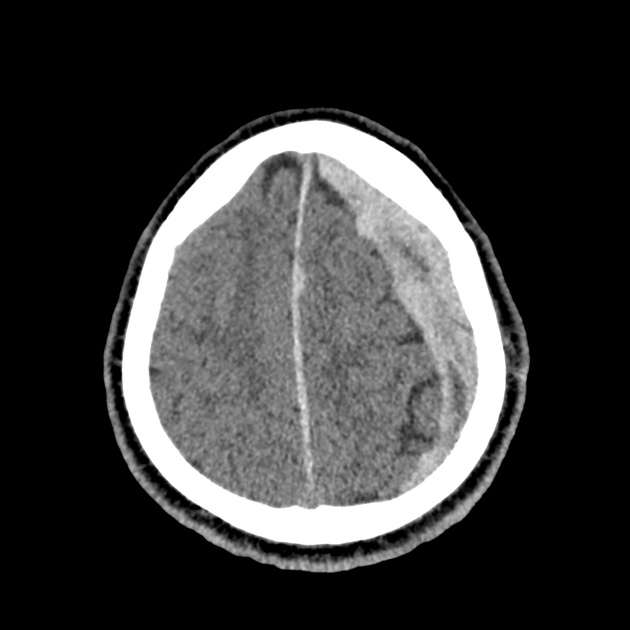

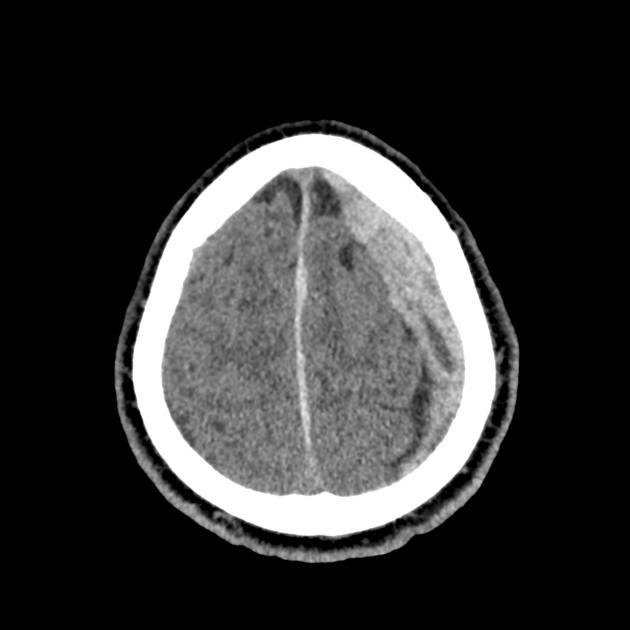

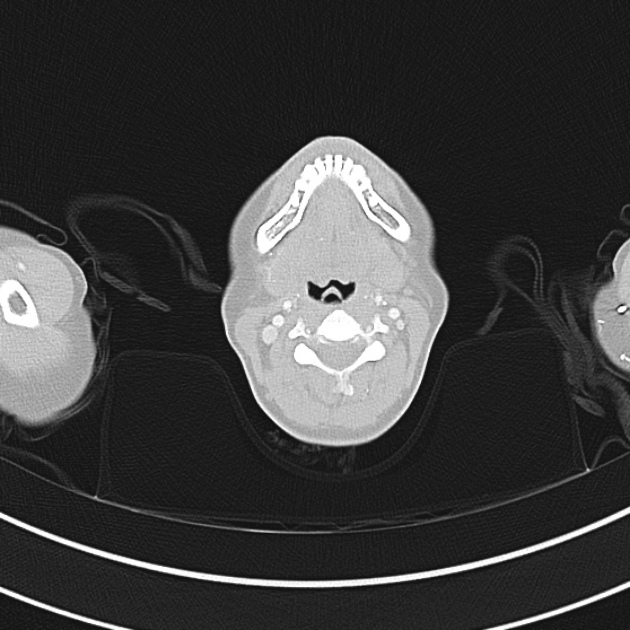

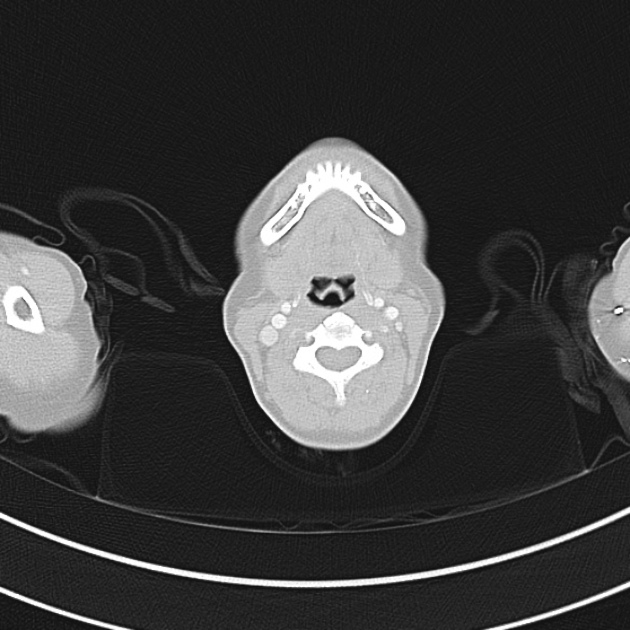

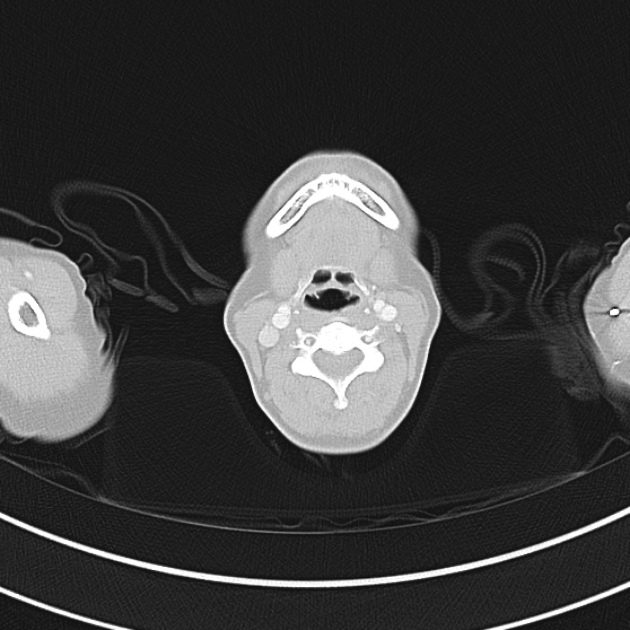

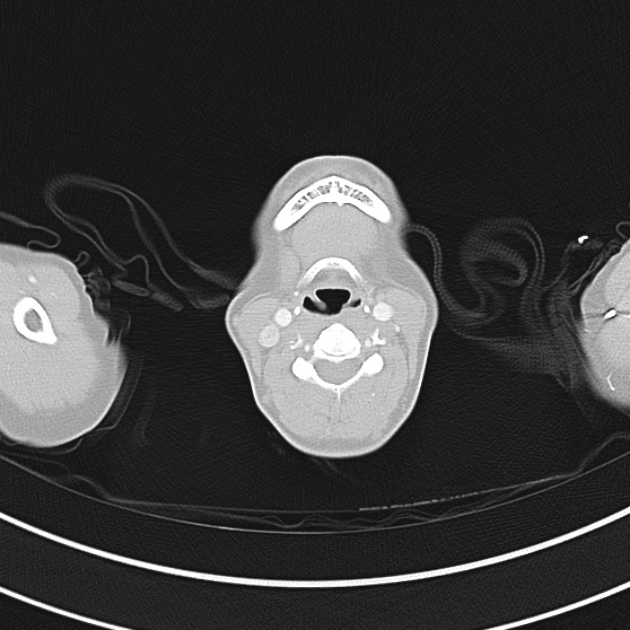

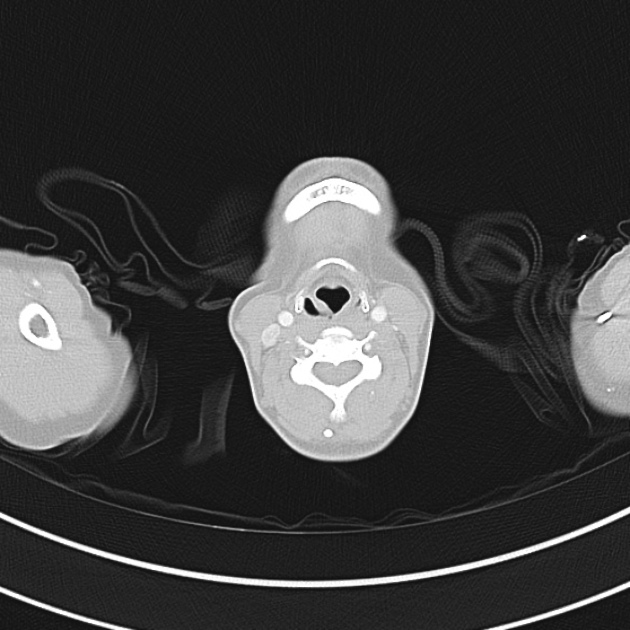

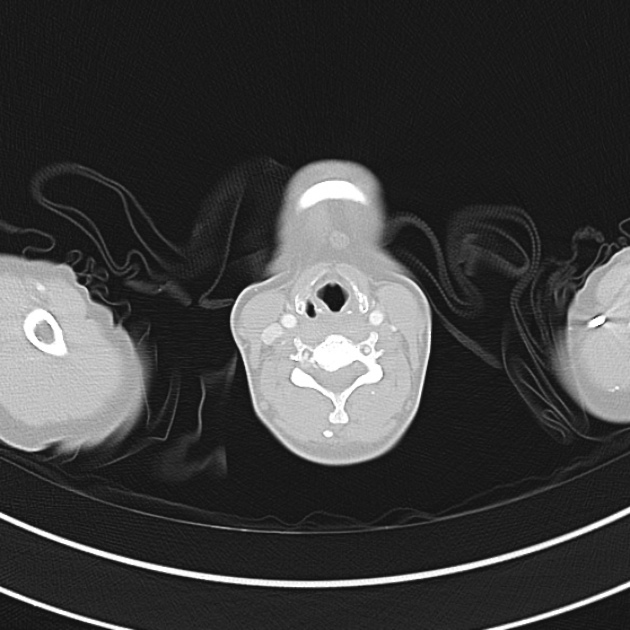

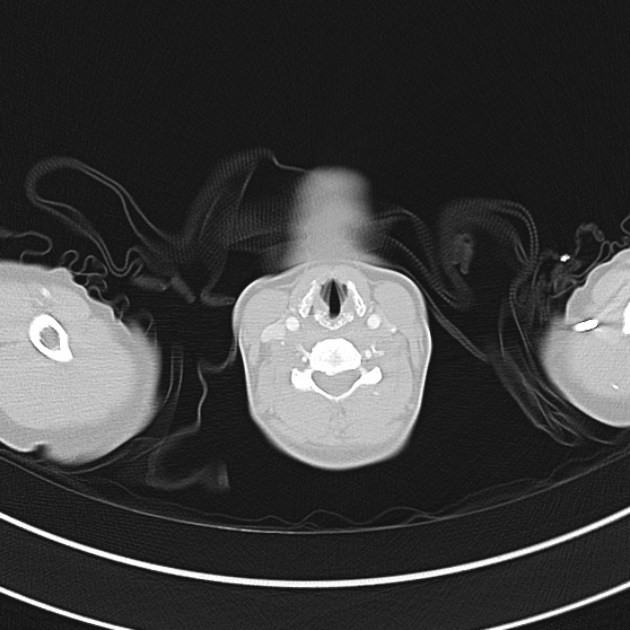

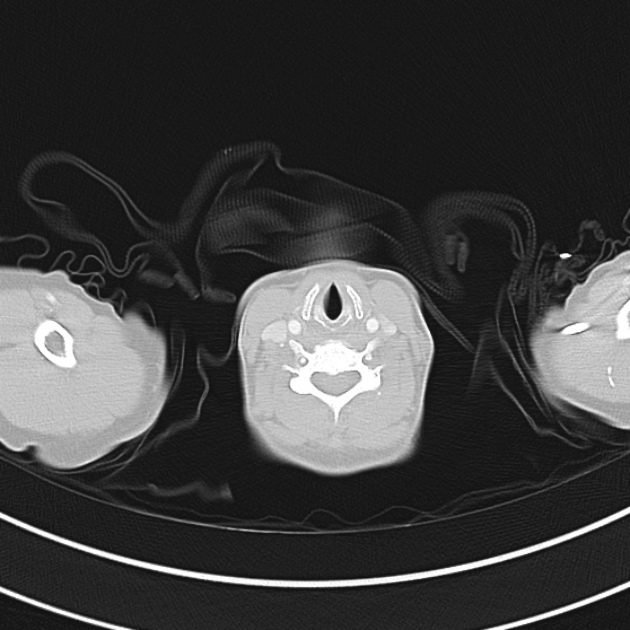

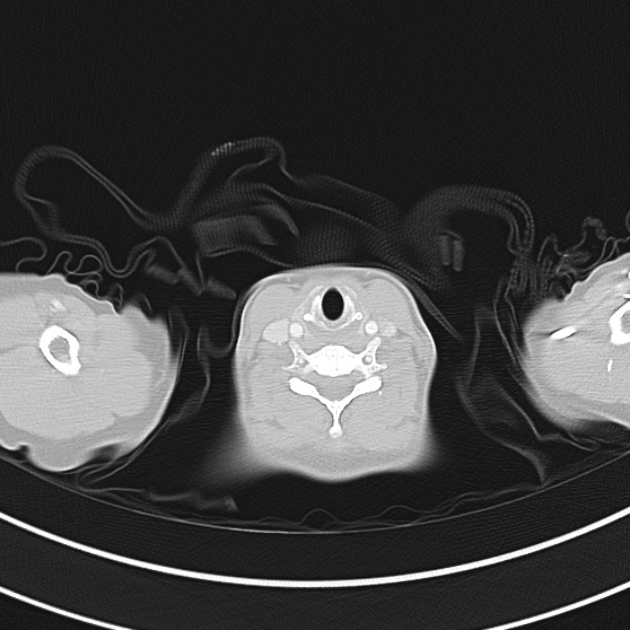

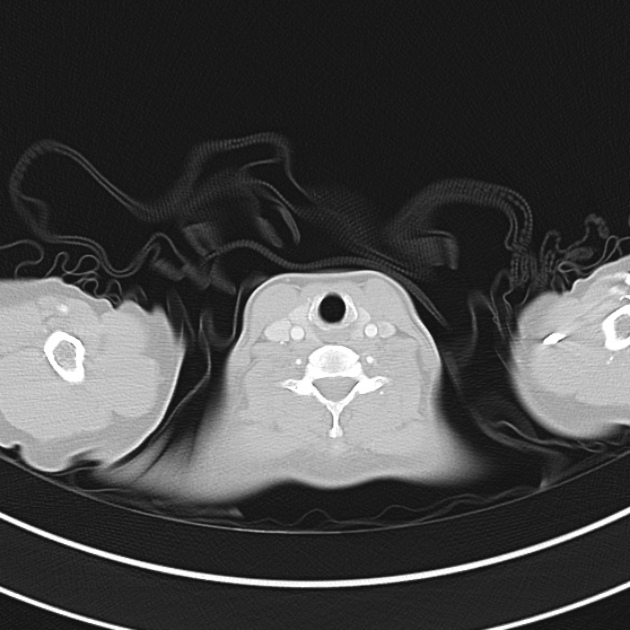

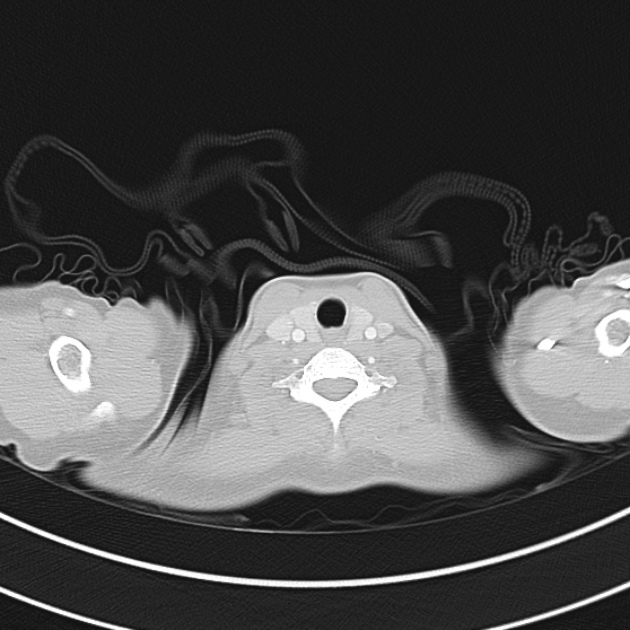

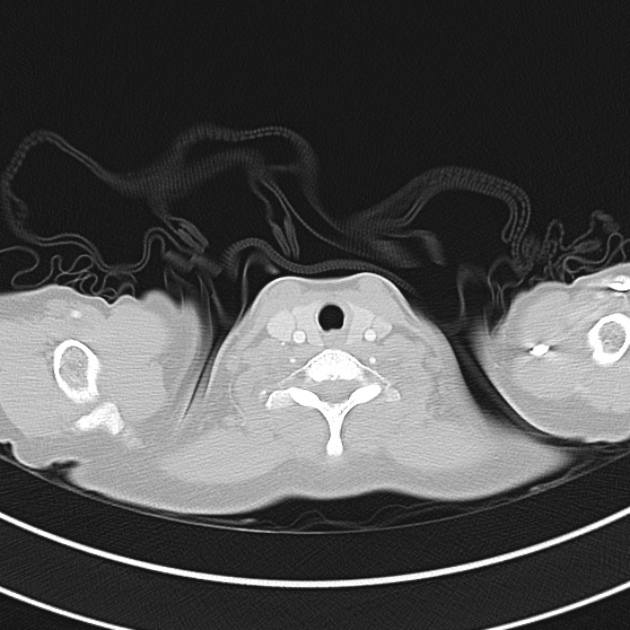

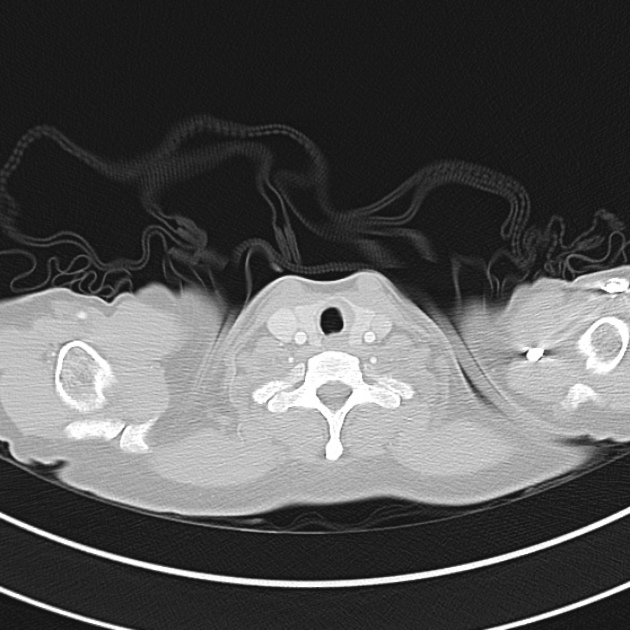

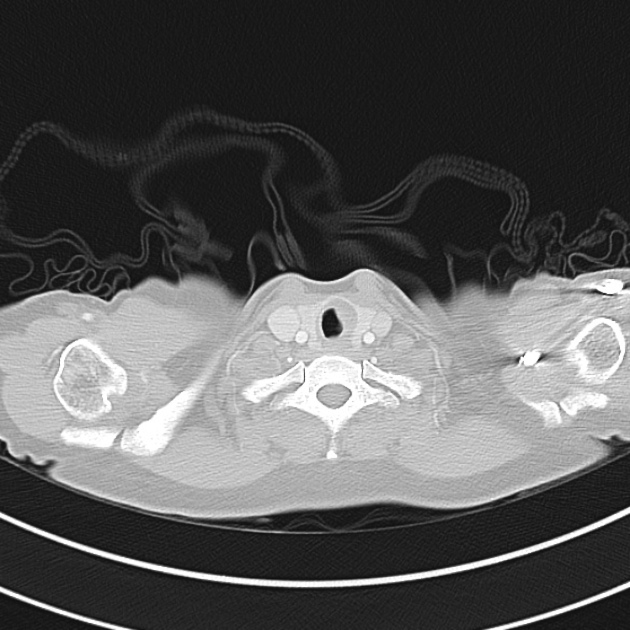

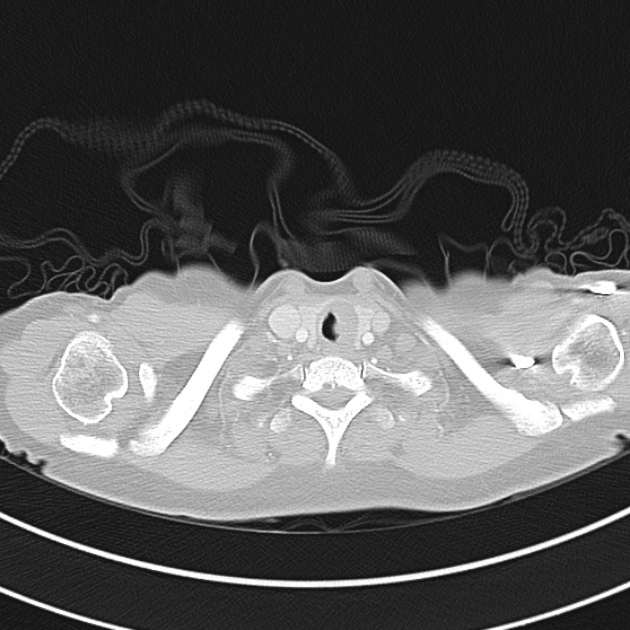

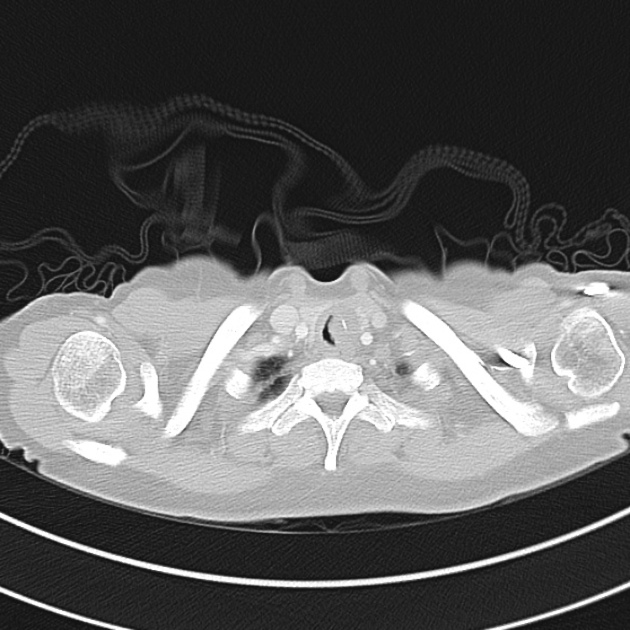

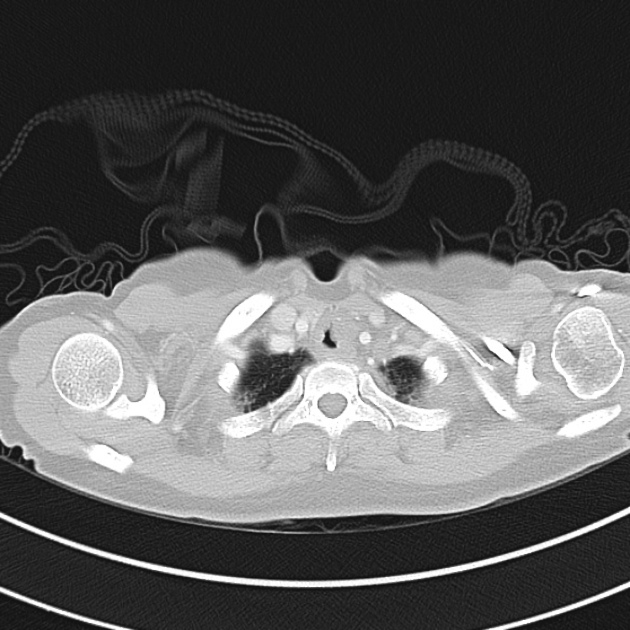

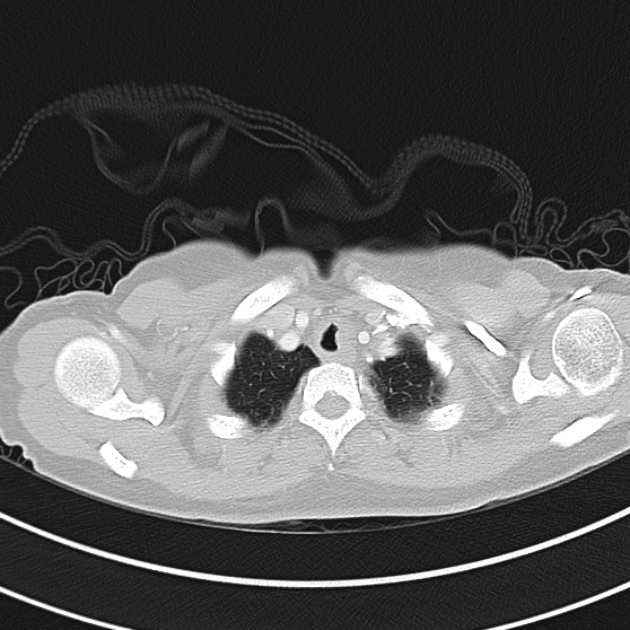

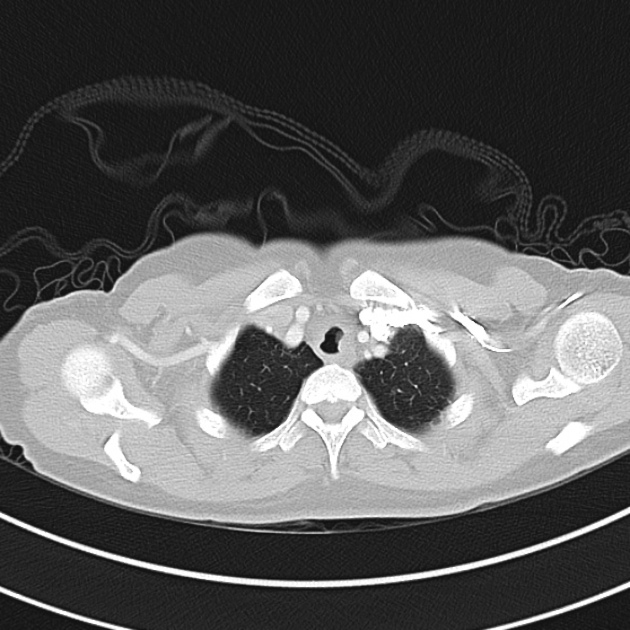

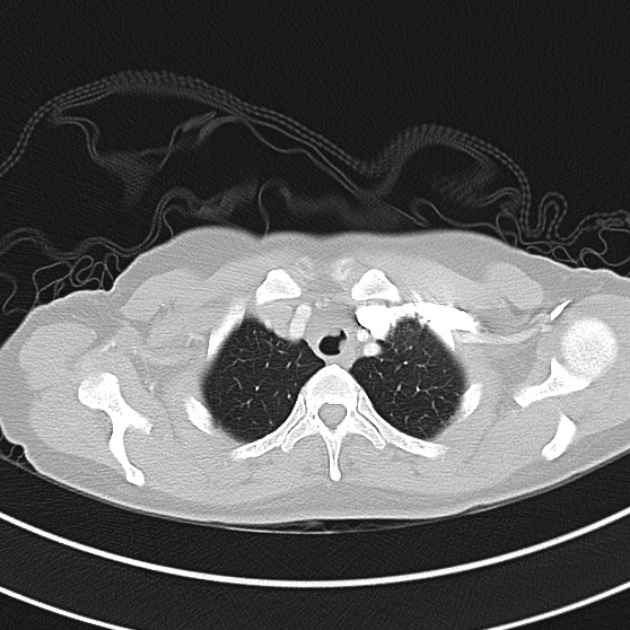

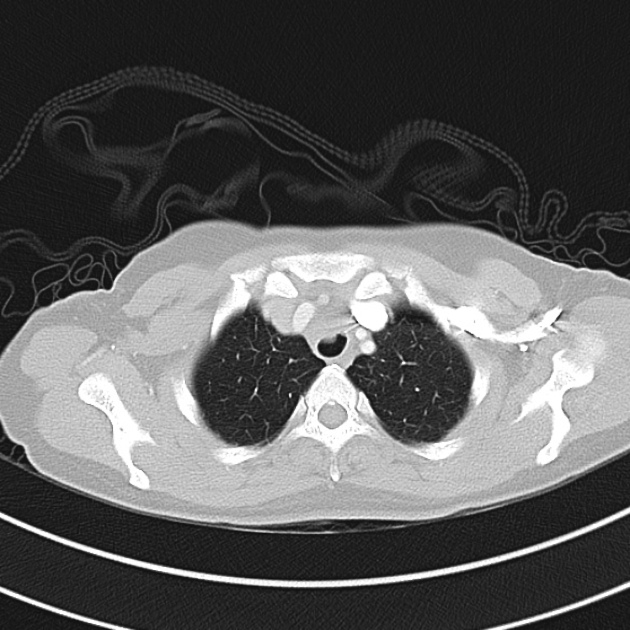

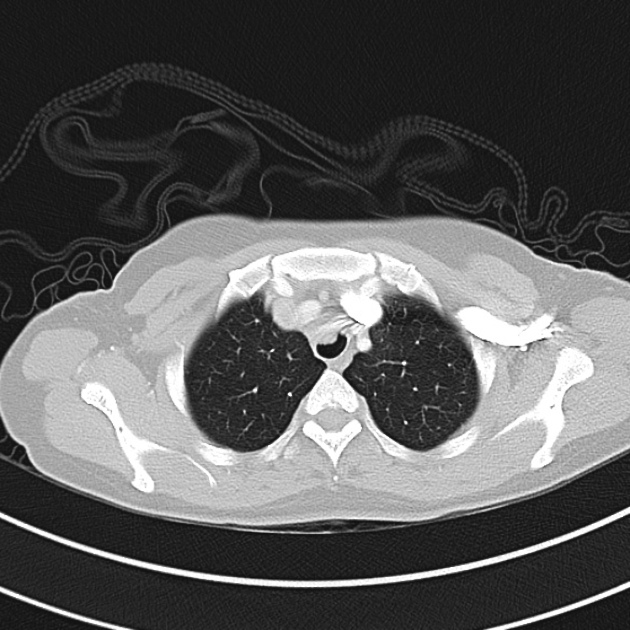

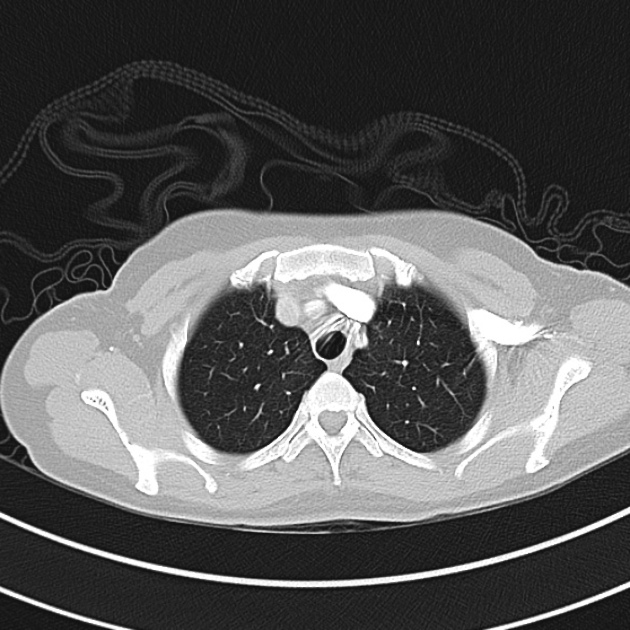

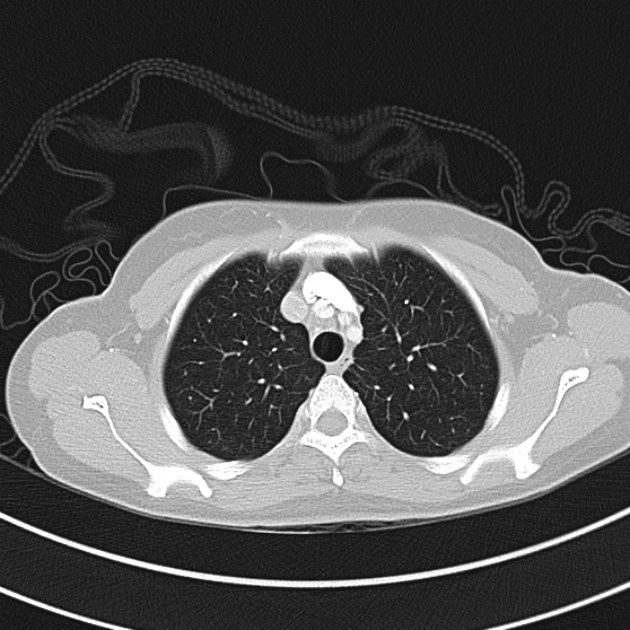

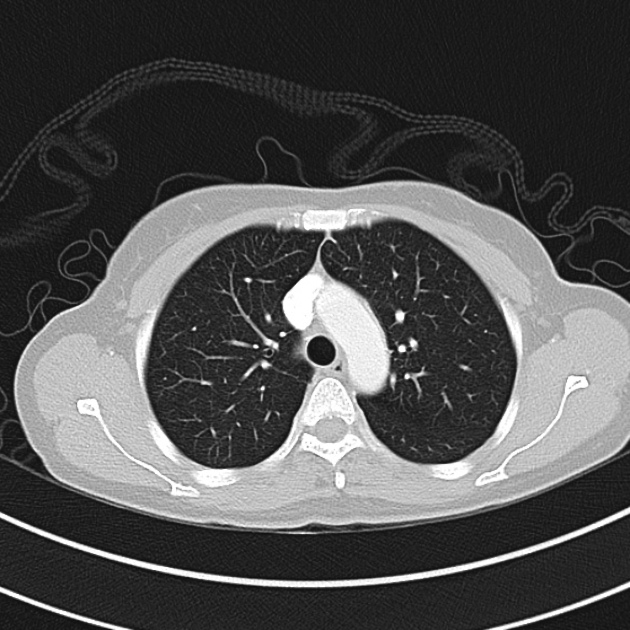

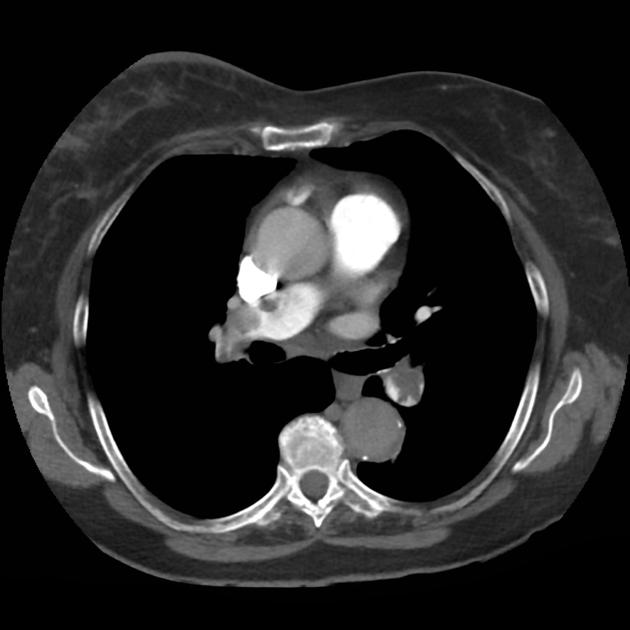

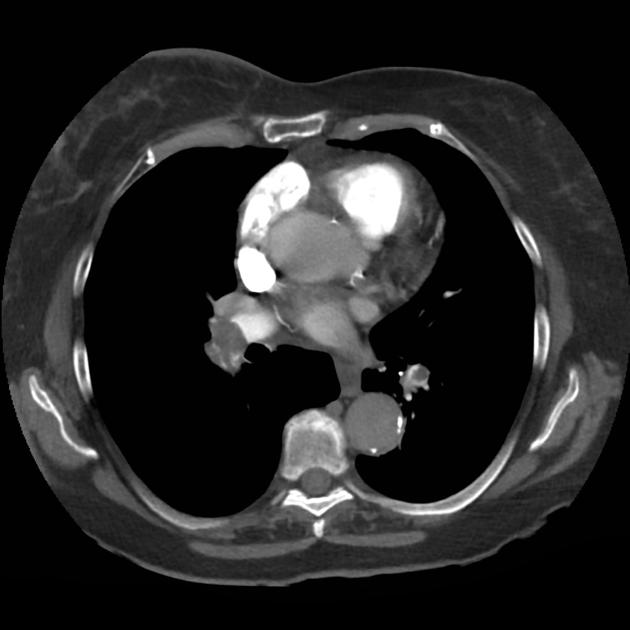

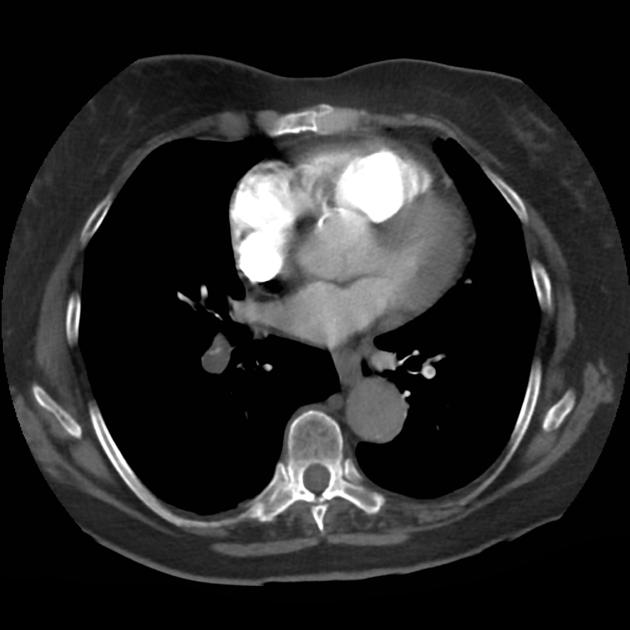

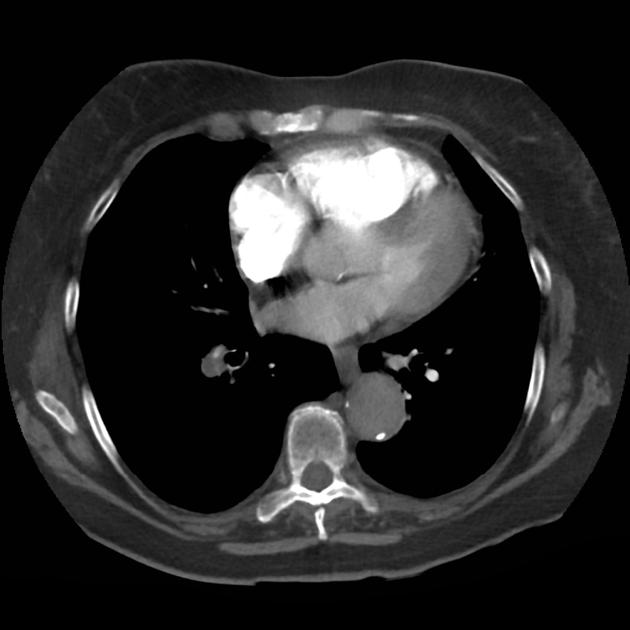

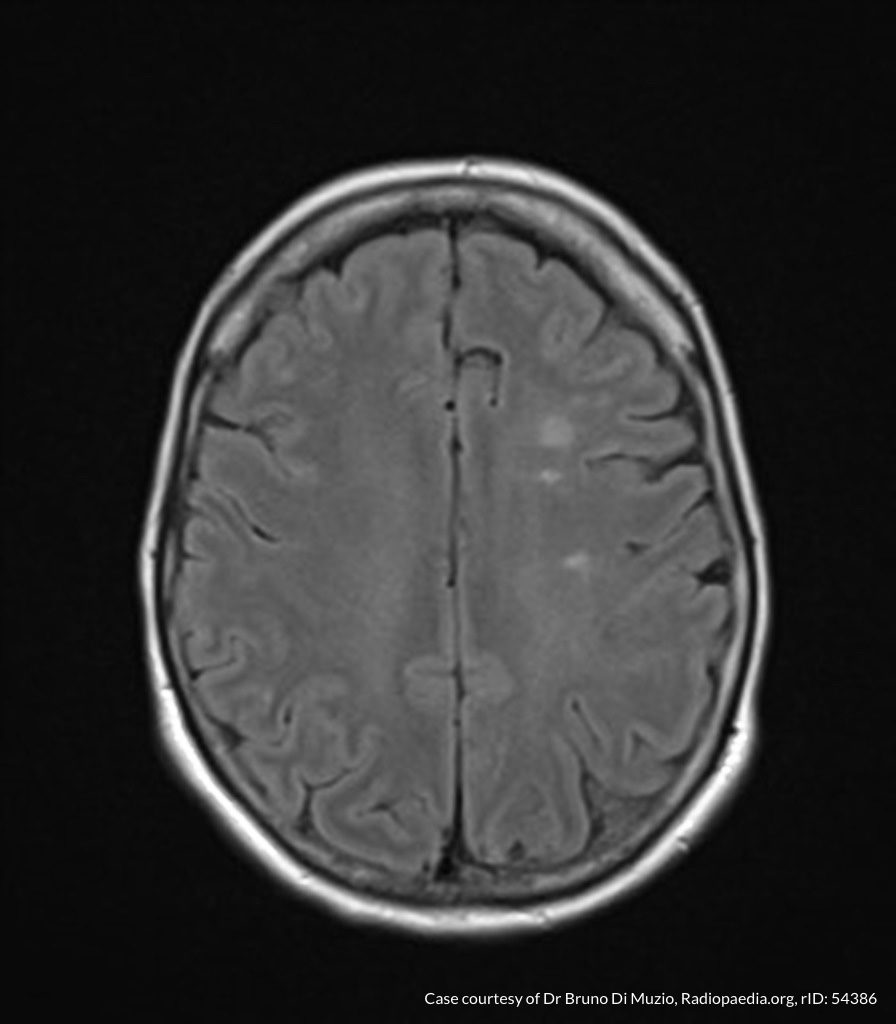

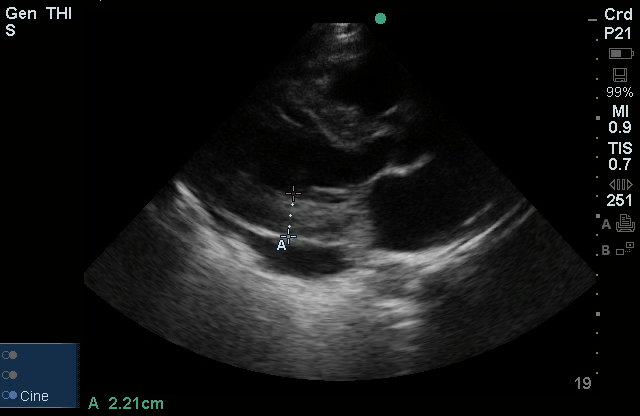

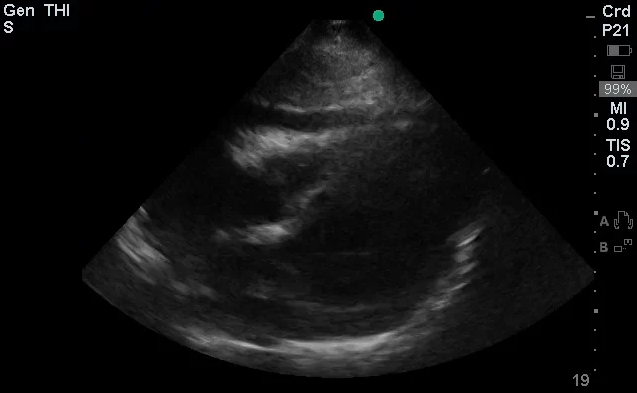

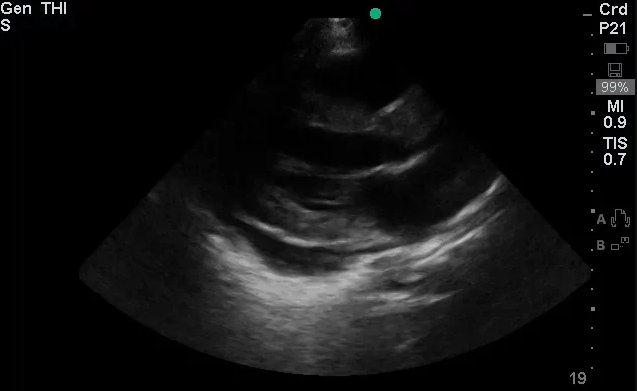

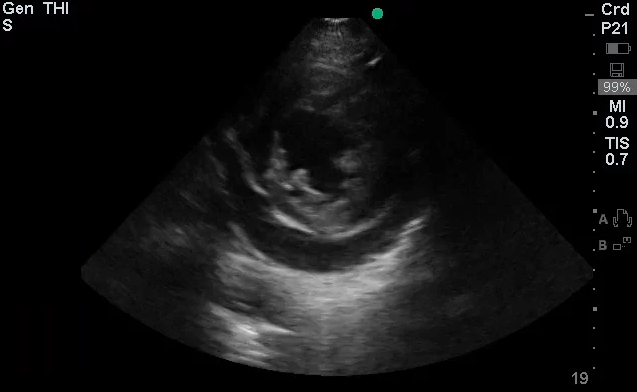

CT Head:

Left cerebral convexity acute subdural hematoma producing substantial mass effect with midline shift and left uncal herniation.

Case courtesy of Dr Andrew Dixon, Radiopaedia.org. From the case rID: 32395

A nicardipine infusion is initiated and the head of the bed is elevated. Andexanet Alfa is not available, therefore an infusion of 4-Factor PCC is initiated. The patient is taken emergently to the operating room by neurosurgery for craniotomy and hematoma evacuation.

An Algorithm for the Reversal of Anticoagulation for Intracranial Hemorrhage 1-4

All Agents

For all agents, discontinue anticoagulation. Patients may require blood pressure control including anti-hypertensive infusions (goal SBP <140). Avoid reversal for intracranial hemorrhage associated with cerebral venous thrombosis. Use cautiously in patients with concomitant life-threatening ischemia, thrombosis, or severe DIC.

Vitamin K Antagonists (ex. warfarin)

Initial Dose

A fixed dose of 4F-PCC 1500 to 2000 units can be given as an initial dose with repeat dosing based on INR measurement 15 minutes after completion of infusion. Follow local institution guidelines if available.

Monitoring and Repeat Dosing

- Vitamin K: if INR ≥1.4 at 12 hours 5

- 4F-PCC: May consider repeat PCC dosing based on INR, though with increased DIC and thrombotic risk, it is recommended to correct further with FFP if INR remains ≥1.4 6

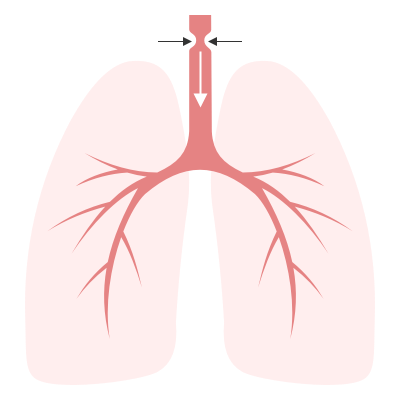

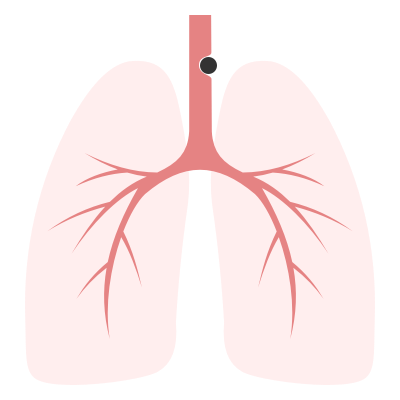

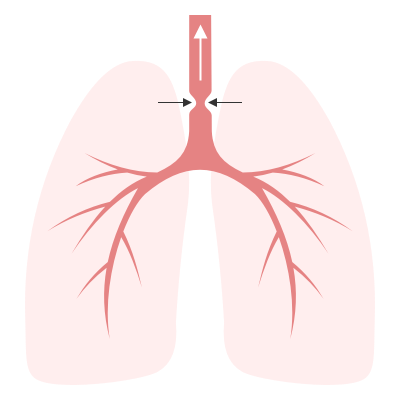

Direct Factor Xa Inhibitors (ex. rivaroxaban, apixaban)

Activated charcoal may be effective for up to six hours for apixaban 7 and eight hours for rivaroxaban 8.

*Andexanet alfa Regimens 9,10

- Low-dose: rivaroxaban <10mg, apixaban <5mg, edoxaban <30mg or 8 or more hours since last dose

- High-dose: If greater than above thresholds, or dose/timing unknown

Pentasaccharides (ex. fondaparinux)

Use high-dose Andexanet alfa regimen 12

Direct Thrombin inhibitors (ex. dabigatran)

Monitoring and Repeat Dosing

If ongoing significant bleeding after treatment, consider redosing idarucizumab and/or hemodialysis.

Alternative Regimens

If idarucizumab is not available, aPCC (50-80 units/kg) , 4F-PCC or 3F-PCC (50 units/kg) can be used in order of preference.

Unfractionated Heparin

Dosing

Determination of units of heparin is based on estimated active agent (half-life 1-2 hours)

- Protamine sulfate 1mg/100 units IV, maximum dose 50mg

- Alternatively, can give fixed dose of 25-50mg

Monitoring and Repeat Dosing

If aPTT is persistently elevated, repeat 0.5 mg/100 units

Low-Molecular Weight Heparin 13

Reversal is not indicated if more than 3-5 half-lives have passed since administration:

- Enoxaparin mean half-life: 4-5 hours

- Dalteparin mean half-life: 2.8 hours

- Nadroparin mean half-life: 3.7 hours

If bleeding persists, or renal insufficiency, repeat dose .5 mg/1 mg enoxaparin or .5 mg/100 anti-Xa units.

This algorithm was developed by Dr. Taylor Martin. Taylor is an emergency medicine resident at McGovern Medical School at UTHealth Houston.

References

Guidelines & Reviews

- Greenberg SM, Ziai WC, Cordonnier C, et al. 2022 guideline for the management of patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. Published online May 17, 2022:101161STR0000000000000407.

- Tomaselli GF, Mahaffey KW, Cuker A, et al. 2020 acc expert consensus decision pathway on management of bleeding in patients on oral anticoagulants: a report of the american college of cardiology solution set oversight committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(5):594-622.

- Frontera JA, Lewin JJ, Rabinstein AA, et al. Guideline for reversal of antithrombotics in intracranial hemorrhage: a statement for healthcare professionals from the neurocritical care society and society of critical care medicine. Neurocrit Care. 2016;24(1):6-46.

- Freeman, W. David, Weitz, Jeffrey. “Reversal of anticoagulation in intracranial hemorrhage.” UpToDate. (2022) https://www.uptodate.com/contents/reversal-of-anticoagulation-in-intracranial-hemorrhage?search=anticoagulation%20reversal (Accessed on May 26, 2022)

Vitamin K Antagonists

- Ansell J, Hirsh J, Hylek E, Jacobson A, Crowther M, Palareti G. Pharmacology and management of the vitamin k antagonists: american college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines(8th edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):160S-198S.

- Pabinger I, Brenner B, Kalina U, et al. Prothrombin complex concentrate (Beriplex p/n) for emergency anticoagulation reversal: a prospective multinational clinical trial. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(4):622-631.

Direct Factor Xa Inhibitors

- http://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_eliquis.pdf

- https://www.bayer.com/sites/default/files/2020-11/xarelto-pm-en.pdf

- Demchuk AM, Yue P, Zotova E, et al. Hemostatic efficacy and anti-fxa (Factor xa) reversal with andexanet alfa in intracranial hemorrhage: annexa-4 substudy. Stroke. 2021;52(6):2096-2105.

- Cohen AT, Lewis M, Connor A, et al. Thirty-day mortality with andexanet alfa compared with prothrombin complex concentrate therapy for life-threatening direct oral anticoagulant-related bleeding. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2022;3(2):e12655.

- Scaglione F. New oral anticoagulants: comparative pharmacology with vitamin K antagonists. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2013;52(2):69-82.

Pentasaccharides (ex. fondaparinux)

- Lu G, DeGuzman FR, Hollenbach SJ, et al. A specific antidote for reversal of anticoagulation by direct and indirect inhibitors of coagulation factor Xa. Nat Med. 2013;19(4):446-451.

Low-Molecular Weight Heparin

- Fareed J, Hoppensteadt D, Walenga J, et al. Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties of enoxaparin : implications for clinical practice. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42(12):1043-1057.