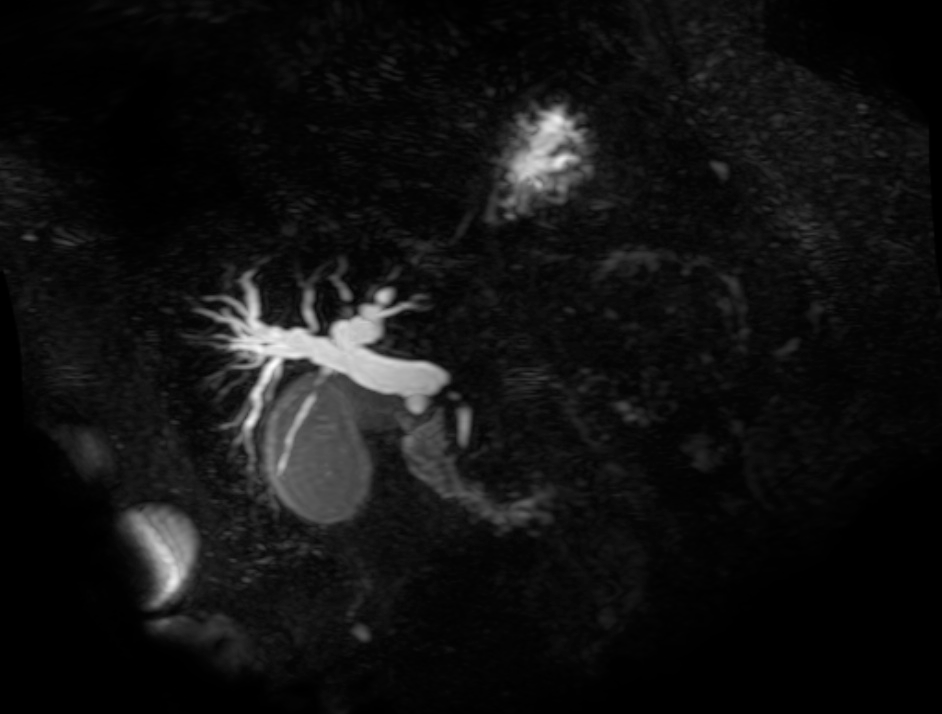

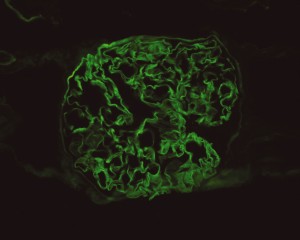

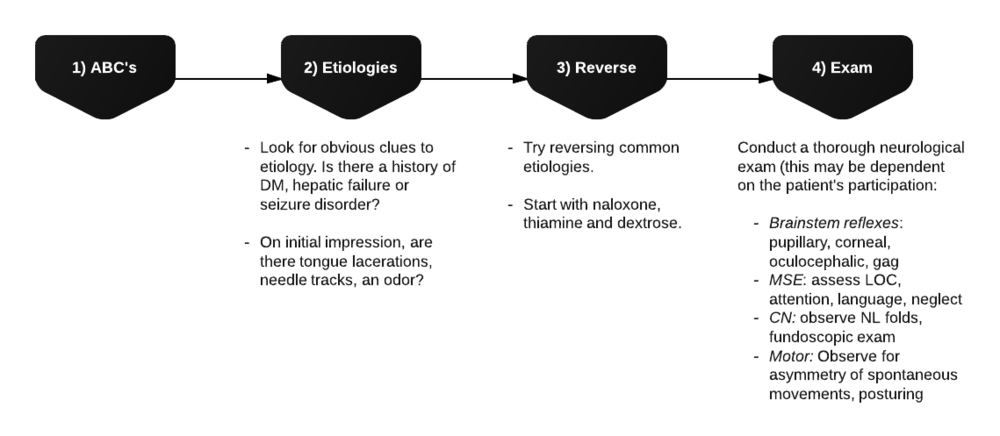

Linear IgG deposits consistent with anti-GBM disease.

CC:

“bad cough”

HPI:

61yo African American female w/hx of HTN presenting with 1mo of persistent cough productive of green-yellow sputum, noticed streaks of blood for the past 5 days. She came to the ED today because she has been feeling increasingly fatigued. She reports subjective fevers at the onset of symptoms which has resolved. She denies shortness of breath, chest pain, chills, night sweats. She sought medical care for this problem 2wk ago and was treated with amoxicillin and a cough suppressant. She recalls a coworker was ill one month ago. She is US-born, had a negative PPD in the past and has no known exposures to tuberculosis.

Of note, the patient reports her urine had a foamy appearance and has been darker in color beginning 3 weeks ago, but this had resolved. She denied dysuria, or frank hematuria.

PMH:

- HTN

- Asthma – last required medications >30yrs ago

|

PSH:

|

FH:

|

SHx:

- No t/e/d

- Works as librarian

|

Meds:

- benazepril

- amlodipine

- amoxicillin

- promethazine

|

Allergies:

|

Physical Exam:

| VS: |

T |

99.4 |

HR |

97 |

BP |

132/60 |

RR |

20 |

O2 |

92% |

| Gen: |

Well-appearing, pleasant, speaking in complete sentences |

| HEENT: |

PERRL, MMM no lesions, no cervical lymphadenopathy |

| CV: |

RRR, normal S1/S2, no murmur appreciated |

| Lungs: |

Crackles in posterior: right middle/inferior and left inferior fields, no wheezing, no dullness to percussion |

| Abd: |

+BS, soft, non-tender, no CVAT |

| Ext: |

Warm, well-perfused, 2+ peripheral pulses, 1+ pitting edema to knee |

| Skin: |

No lesions on exposed skin |

| Neuro: |

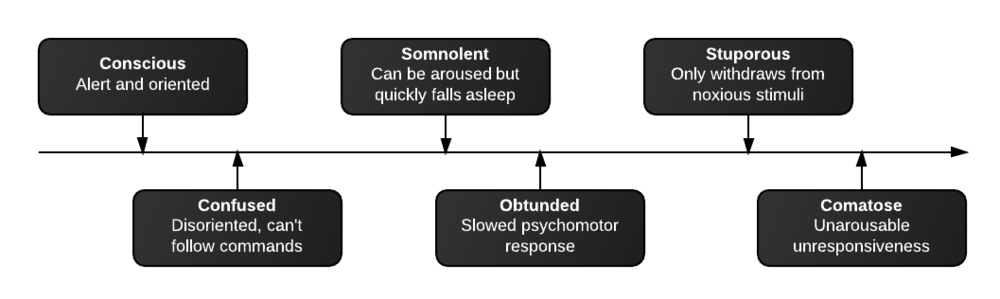

AAO |

Labs:

- CBC: 12.3/6.7/19.8/52.3 (S: 94, B: 1, L: 4, M: 1, MCV: 92.3); baseline Hb/Hct (1/11/2012) 13.4

- BMP: 136/3.6/101/25/46/3.43/126; baseline creatinine (1/11/2012) 1.18

- UA: brown, trace LE, – nitrites, 2+ protein, 81 RBC

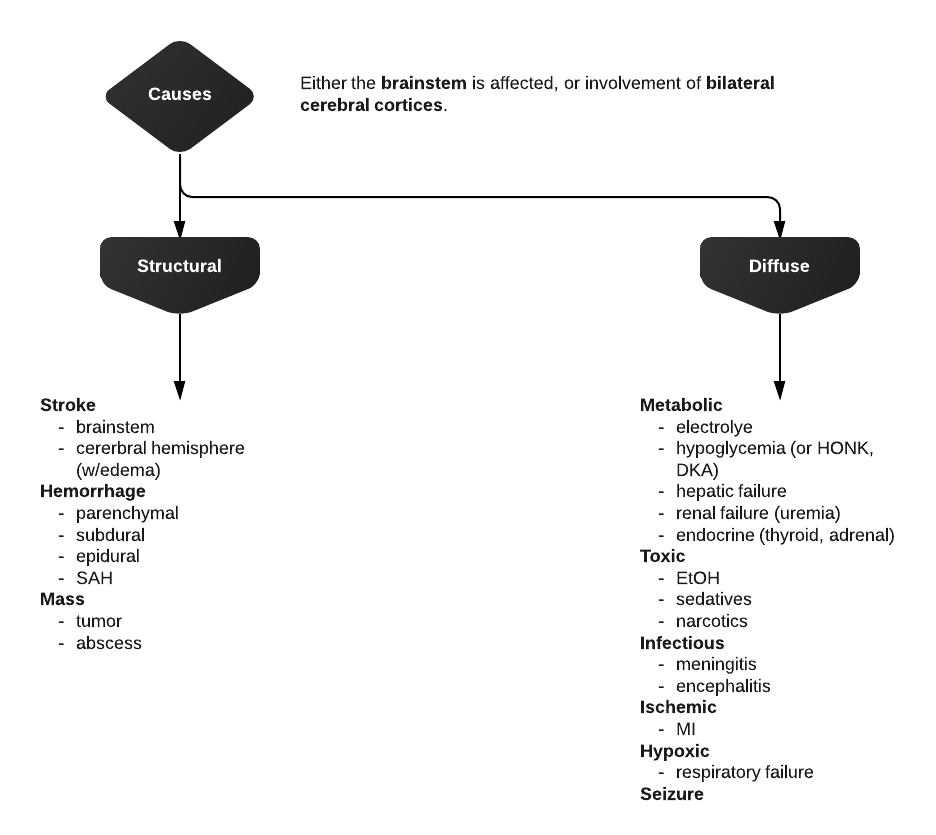

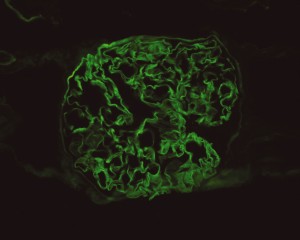

Imaging:

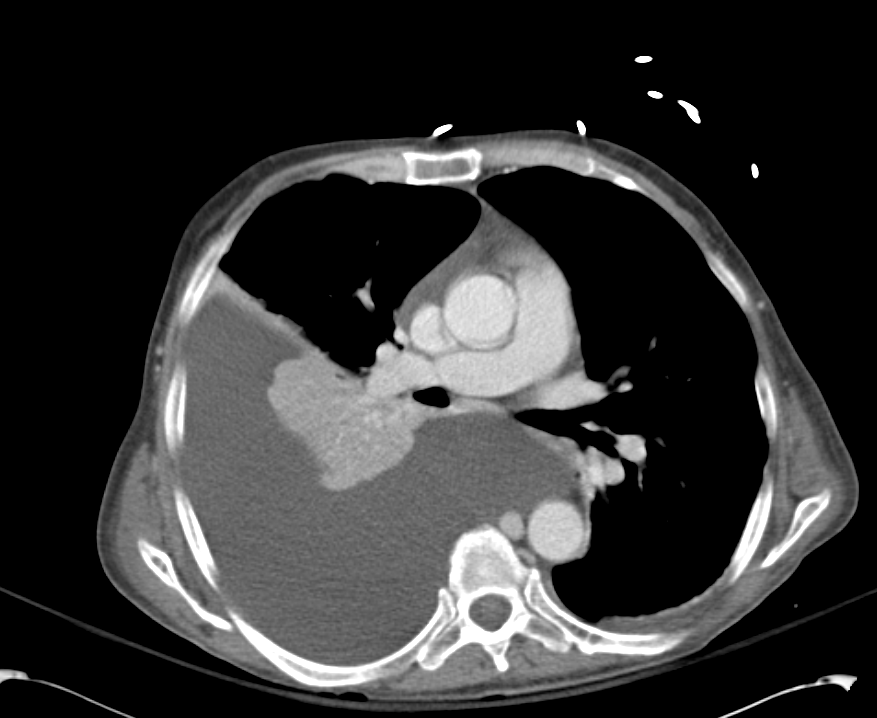

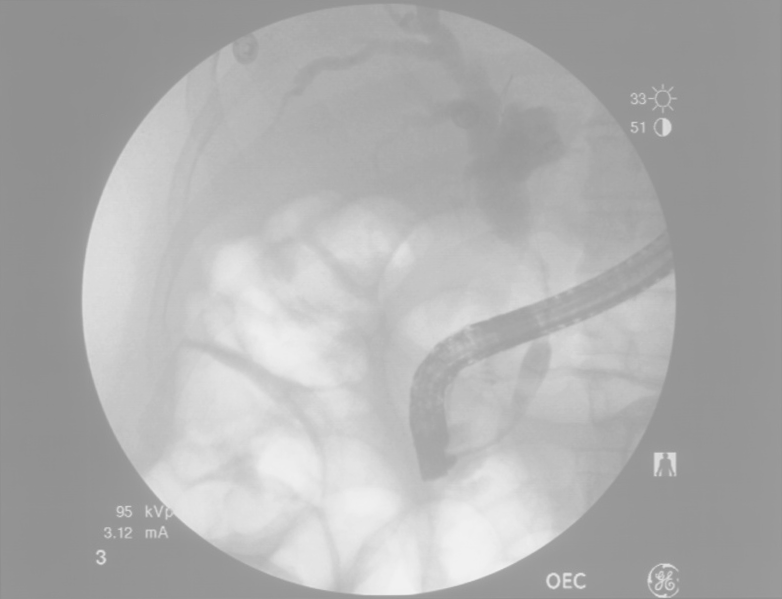

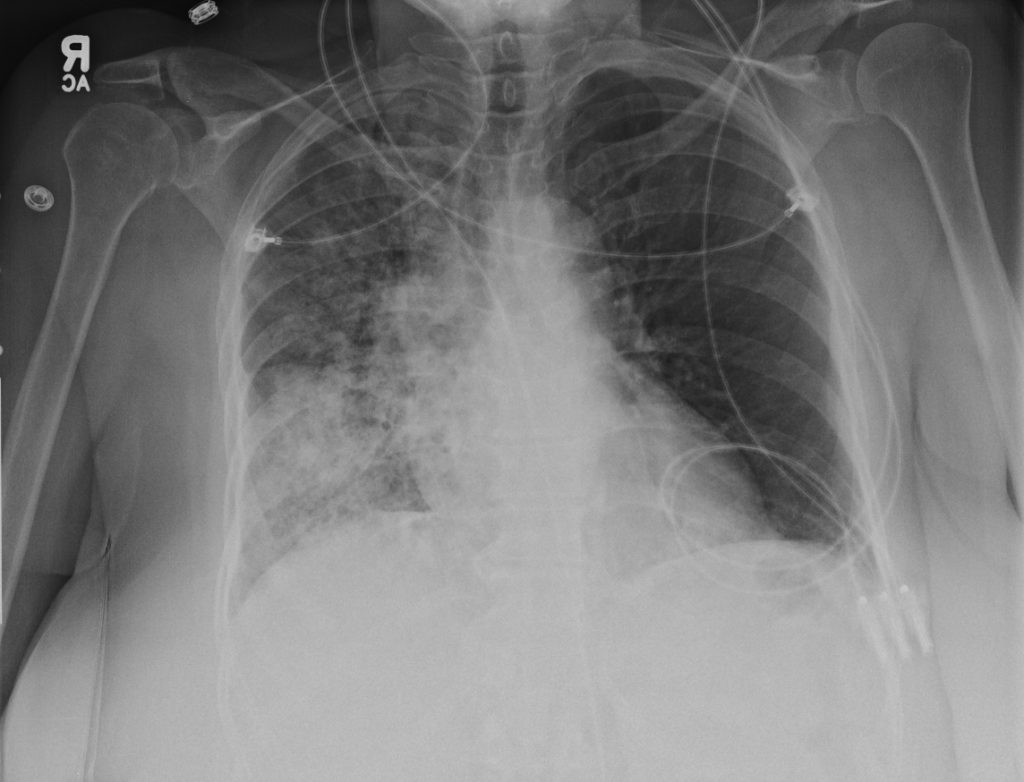

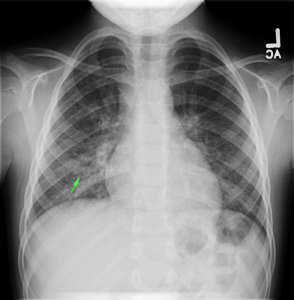

- Right mid-lung zone consolidation is present, suggests pneumonia if acute.

- Mild asymmetric right parenchymal increased density is seen diffusely as well.

Assessment/Plan:

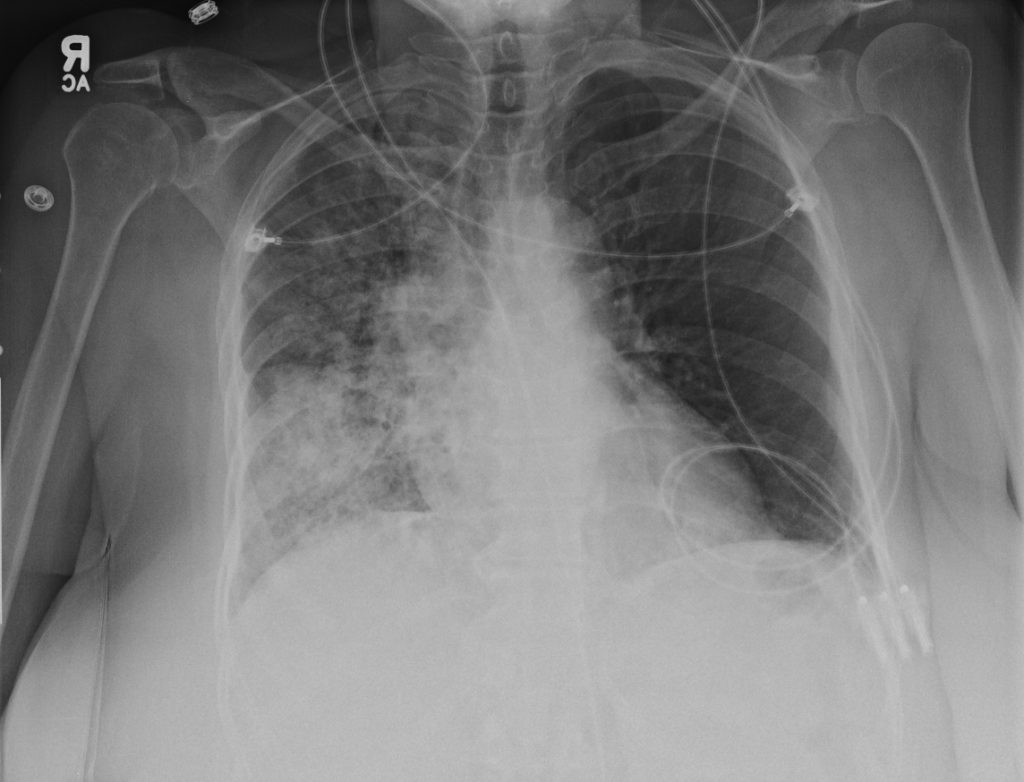

65AAF w/hx HTN presents with persistent productive cough, recently with hemoptysis.

# Cough: Symptoms and physical findings of abnormal breath sounds (crackles, though no strict consolidation) concerning for community-acquired pneumonia. Addition of hemoptysis raises concern for TB, particularly when taking into consideration the duration of cough and presence of constitutional symptoms. CBC shows leukocytosis with left shift, CXR with right mid/lower lob infiltrates consistent with pneumonia. Recommend admission and isolation to rule out TB, start empiric therapy for community acquired pneumonia with ceftriaxone, azithromycin. Obtain induced sputum samples for culture, AFB smear and culture.

# Abnormal urine: Patient describes changes in urine suggestive of proteinuria and hematuria. Acuity of onset and apparent spontaneous resolution suggests a chronic kidney injury 2/2 hypertension is unlikely. Absence of dysuria, or tenderness (suprapubic, costovertebral) suggests complicated UTI unlikely. Urinalysis notable for 2+ protein and significant RBC’s, possible nephritic syndrome. In the setting of hemoptysis, this raises concern for anti-GBM disease vs. vasculitis.

# Anemia: Normocytic anemia. No evidence of acute, life-threatening hemorrhage as patient is currently hemodynamically stable. Possible sites of blood loss include alveoli, glomeruli. Given that patient sought care today for worsening fatigue, will monitor hemoglobin closely and consider transfusion. Obtain iron studies.

# HTN: BP stable, hold home medications.

Interval History:

The patient was admitted for management of community-acquired pneumonia and isolation to rule out TB. Empiric therapy with CTX + azithromycin was continued. On HOD1, the patient was transfused two units of PRBC’s. On HOD2, the patient underwent CT chest/abdomen/pelvis due to worsening respiratory status despite antimicrobial therapy. On HOD3, the patient went into atrial fibrillation with RVR which was converted to sinus rhythm with metoprolol 5mg IV x3. On HOD5, nephrology consult recommended starting steroid therapy, plasmapheresis and obtaining a renal biopsy, however the biopsy was delayed due to worsening respiratory status.

Interval Labs:

- Iron studies: Fe 8, TIBC 203, Ferritin 468, haptoglobin 333, retics 2.7

- Inflammatory markers: ESR 120, CRP 34

- Micro: BCx NGTD, RCx moderate Candida, sputum AFB smear negative x3

- LFT: AST 34, ALT 29, ALP 52, protein 6.3, albumin 2.4, T.bil 0.8, D.bil 0.2

- Quant-gold: negative

- Anti-GBM 1.2 (nl <1.0)

- p-ANCA: positive 1:640, [ELISA pending]

- ANA: positive 1:320, speckled

- HIV: negative

Interval Imaging:

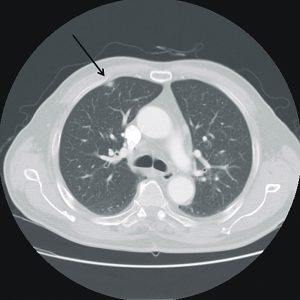

CT Chest

- Diffuse right lung, tree and bud opacities, ground-glass opacities and areas of confluence with scattered air bronchograms. Less severe similar pattern in the left lung as well particular at the base.

- Right paratracheal, subcarinal and perihilar LAD.

- Findings concerning for primary TB in the right clinical setting. DDx nonspecific bacterial PNA and fungal PNA.

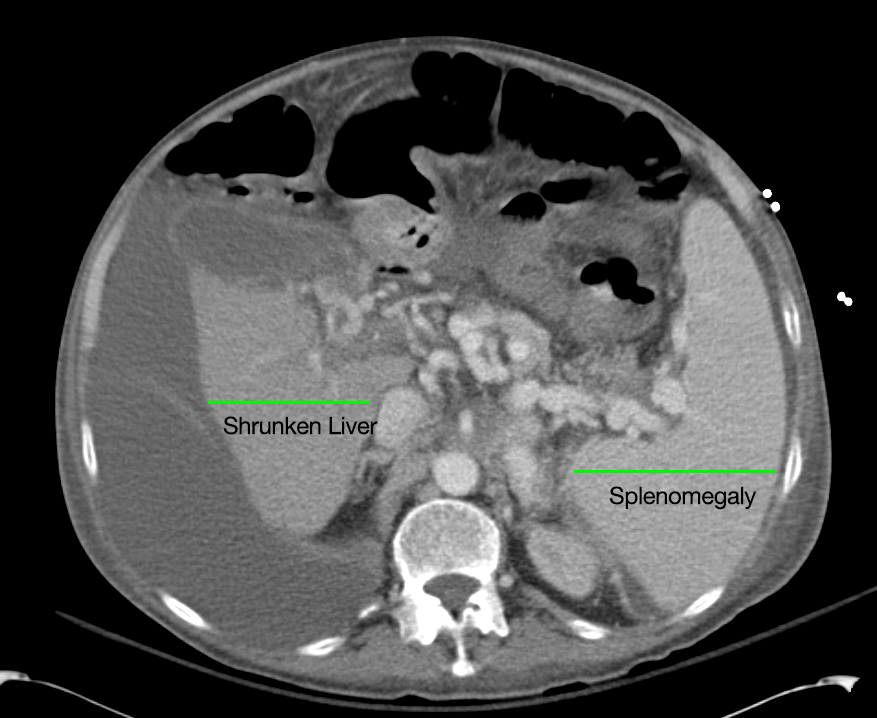

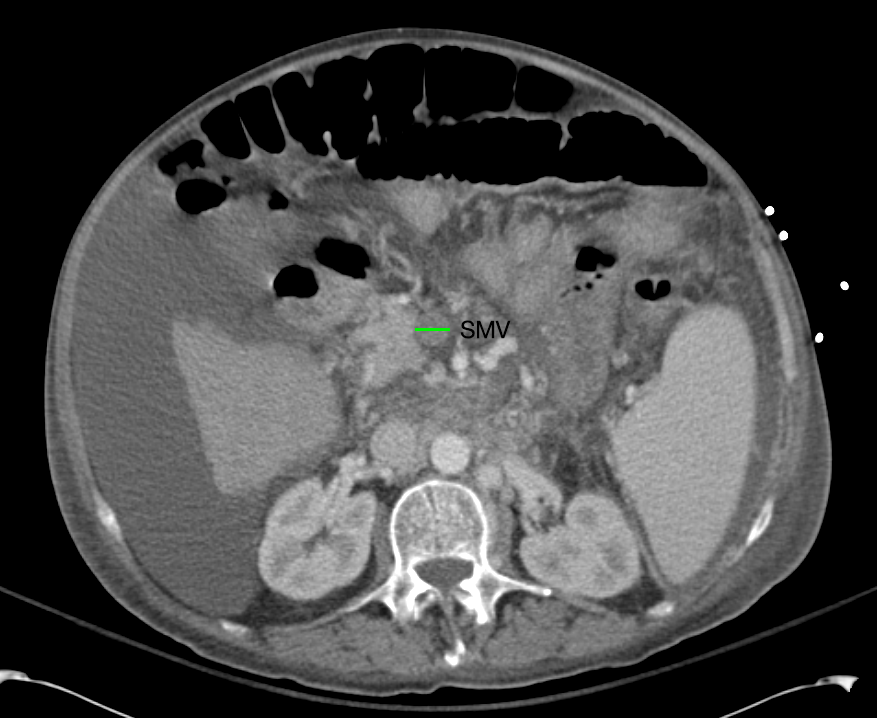

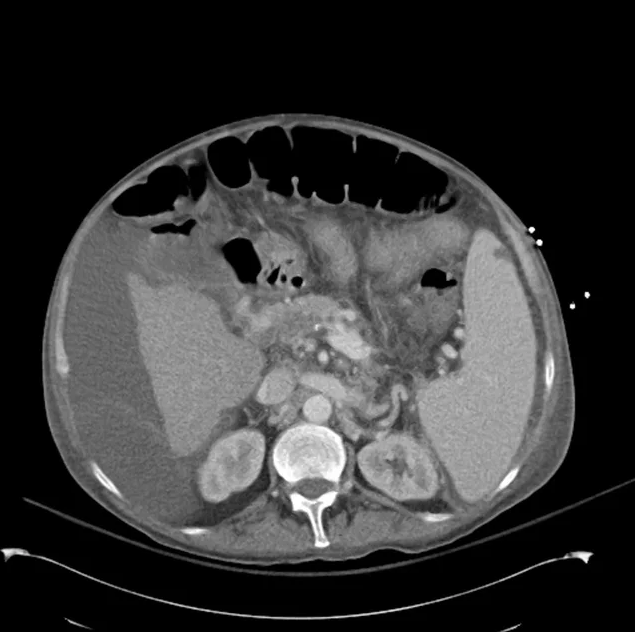

CT Abdomen/Pelvis

- Mild nonspecific R > L perinephric stranding.

Interval Assessment/Plan:

# Acute respiratory failure: Unlikely simple CA-PNA given worsening status while on appropriate antibiotic therapy. Active tuberculosis possible given history of chronic productive cough with hemoptysis, constitutional symptoms and imaging findings. IGRA’s of limited utility in diagnosis of active disease, further, while three negative sputum AFB smears decreases the likelihood of TB, additional testing with NAAT and culture is required. Another possibility is a vasculitic process given concomitant hematuria and acute renal failure, with respiratory symptoms now 2/2 alveolar hemorrhage. This was evaluated with ANCA assay which was positive for p-ANCA with high titer. This is often suggestive of primary vasculitis (in this case likely microscopic polyangiitis vs. Churg-Strauss), however ELISA for target antigen is of particular importance as p-ANCA with specificity for antigens other than MPO can be associated with another condition on the differential: Goodpasture’s syndrome. This patient was found to have elevated anti-GBM antibodies which are highly suggestive of Goodpasture’s syndrome, and can be associated with ANCA-positivity (often suggesting a poorer prognosis with decreased likelihood of recovery of renal function).1

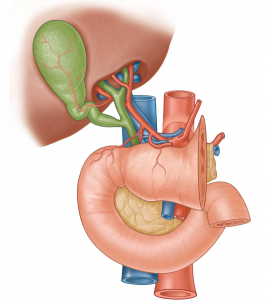

# Acute kidney injury: The patient had significant elevation of serum creatinine compared to last-recorded baseline. She also described darkening and foamy appearance of urine 3 weeks prior to admission, suggestive of proteinuria/hematuria of relatively acute onset. This was supported by urinalysis findings of protein and RBC’s (with casts). Given presence of anti-GBM antibodies, high specificity of such findings, and correlation with glomerulonephritis with evidence of pulmonary alveolar hemorrhage, this appears to be the most likely cause at this time. Definitive diagnosis with renal biopsy to be obtained following stabilization of respiratory status. Patient will be started on plasmapheresis and immunosuppressive therapy (corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide).

# Normocytic Anemia: Likely combination of acute blood loss (2/2 hematuria, pulmonary alveolar hemorrhage) and chronic disease. Normocytic anemia with some reticulocytosis suggestive of acute blood loss, however iron studies with low Fe, TIBC and elevated ferritin suggest chronic disease as an associated factor.

Differential Diagnosis of Hemoptysis: 2, 3

A System for the Diagnosis of Tuberculosis: 4, 5

A System for Vasculitides: 8, 9

Vasculitis Mimics: 9

Interpretation of antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies (ANCA): 10

| Pattern |

Target |

Associated vasculitis |

Other diseases |

| C-ANCA |

PR3 |

- Granulomatosis with polangiitis (Wegener’s)

- Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss)

- Microscopic polyangiitis

- Pauci-immune glomerulonephritis

|

|

| C-ANCA (atypical) |

BPIMPO |

|

|

| P-ANCA |

MPO |

- Microscopic polyangiitis

- Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss)

- Pauci-immune glomerulonephritis

|

|

| Non-MPO |

|

- Autoimmune hepatitis

- IBD, PSC

- SLE, RA

- Drugs

- Infection (HIV, fungal)

|

Differential Diagnosis of Anemias: 11

References:

- Levy, J. B., Hammad, T., Coulthart, A., Dougan, T., & Pusey, C. D. (2004). Clinical features and outcome of patients with both ANCA and anti-GBM antibodies. Kidney international, 66(4), 1535–1540. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00917.x

- Bidwell, J. L., & Pachner, R. W. (2005). Hemoptysis: diagnosis and management. American family physician, 72(7), 1253–1260.

- Hirshberg, B., Biran, I., Glazer, M., & Kramer, M. R. (1997). Hemoptysis: etiology, evaluation, and outcome in a tertiary referral hospital. Chest, 112(2), 440–444. doi:10.1378/chest.112.2.440

- Campbell, I. A., & Bah-Sow, O. (2006). Pulmonary tuberculosis: diagnosis and treatment. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 332(7551), 1194–1197. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7551.1194

- Zumla, A., Raviglione, M., Hafner, R., & Reyn, von, C. F. (2013). Tuberculosis. The New England journal of medicine, 368(8), 745–755. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1200894

- Diagnostic Standards and Classification of Tuberculosis in Adults and Children. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.161.4.16141

- Laraque, F., Griggs, A., Slopen, M., & Munsiff, S. S. (2009). Performance of nucleic acid amplification tests for diagnosis of tuberculosis in a large urban setting. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 49(1), 46–54. doi:10.1086/599037

- Gross, W. L., Trabandt, A., & Reinhold-Keller, E. (2000). Diagnosis and evaluation of vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford, England), 39(3), 245–252.

- Suresh, E. (2006). Diagnostic approach to patients with suspected vasculitis. Postgraduate medical journal, 82(970), 483–488. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2005.042648

- Rus, V., & Handwerger, B. S. (2000). Clinical value of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Current rheumatology reports, 2(5), 383–389.

- Goljan, E. (2011). Pathology. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier.