HPI:

59F with a reported history of congestive heart failure, presenting with intermittent chest discomfort for three days.

She characterized this discomfort as “heartburn”, describing a mid-epigastric burning sensation radiating up her neck, not associated with exertion, lasting 1-2 hours and resolving with antacids. The patient has poor exercise tolerance at baseline and for the past several years has been able to ambulate only short distances around her home, and states that these symptoms have been worsening in the past week. She denies chest pain on exertion, orthopnea or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. She states that she was diagnosed with congestive heart failure five years ago, but was never prescribed medications.

On further questioning, the patient reports several weeks of mouth and lip pain which has limited oral intake, though no dysphagia to solids or liquids. She otherwise denies fevers/chills, abdominal pain, nausea/vomiting, cough, changes in urinary or bowel habits.

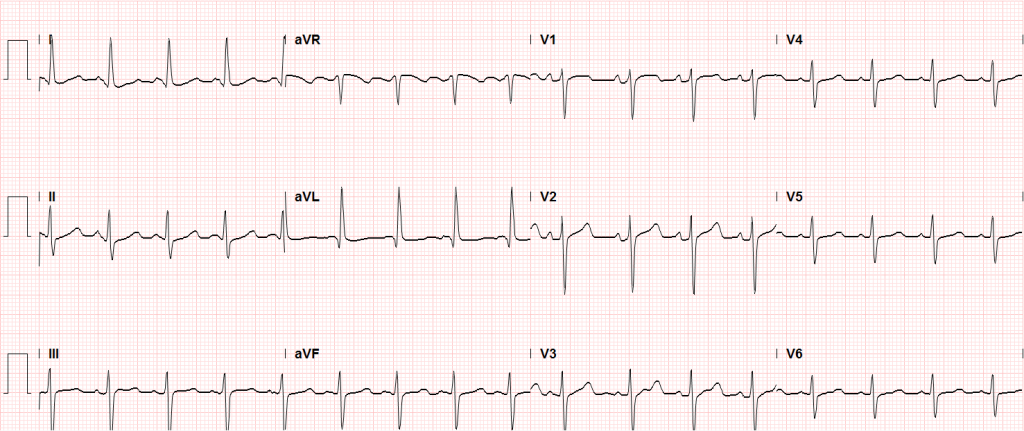

In the emergency department, the patient was noted to have an elevated serum troponin, though ECG showed no changes of acute ischemia/infarction.

FH:

- Mother with diabetes

- Father with MI at age 65

SHx:

- 4-5 drinks of alcohol/day

- No tobacco or drug use

Physical Exam:

| VS: |

T |

37.4 |

HR |

106 |

RR |

18 |

BP |

145/82 |

O2 |

100% RA |

| Gen: |

Morbidly obese female, lying in bed, in no acute respiratory distress, speaking in complete sentences. |

| HEENT: |

Dry, cracked lips, slightly erythematous, otherwise moist mucous membranes, poor dentition. Mild scleral icterus. No cervical lymphadenopathy. |

| CV: |

Rapid rate, regular rhythm, normal S1/S2, II/VI systolic ejection murmur at LUSB, no radiation appreciated. No jugular venous distension. |

| Lungs: |

Clear to auscultation in posterior lung fields bilaterally, no crackles appreciated. |

| Chest: |

Well-circumscribed erythematous patch in folds beneath left breast, no underlying fluctuance, no significant tenderness to palpation. On contralateral breast, some hyperpigmentation but no erythema. |

| Abdomen: |

Obese, non-tender, non-distended. Patch of erythema below pannus, mildly tender to palpation. |

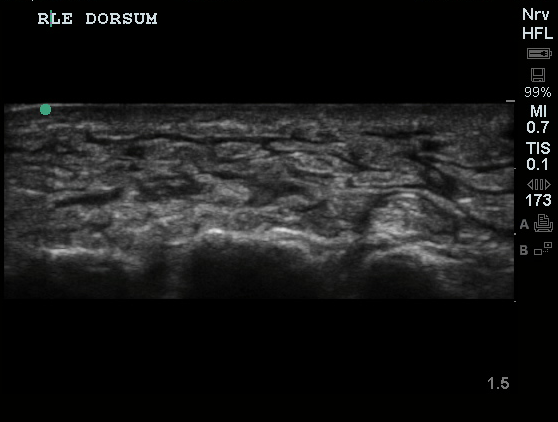

| Ext: |

Bilateral lower extremities with marked edema and overlying scaly plaques, some slightly ulcerated weeping serous fluid. Peripheral pulses are difficult to palpate, capillary refill difficult to assess. |

Labs/Studies:

- CBC: 11.1/11.1/34.5/212 (MCV 114.2)

- BMP: 140/4.5/97/20/10/1.14/64

- Anion Gap: 23

- LFT: AST: 73, ALT: 26, AP: 300, TB: 4.6, DB: 2.1, Alb: 3.0, INR 1.3

- BNP: 158

- Troponin: 1.284

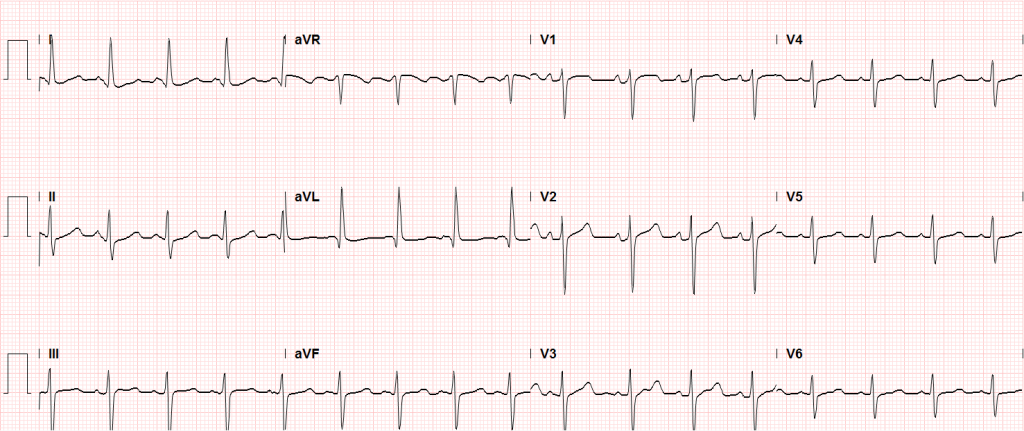

Sinus tachycardia, LVH, secondary repolarization abnormalities

Imaging:

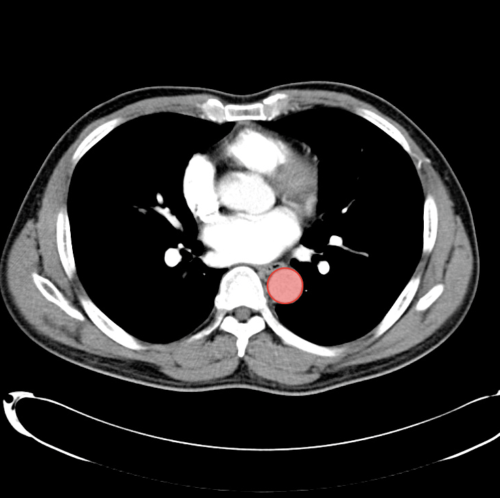

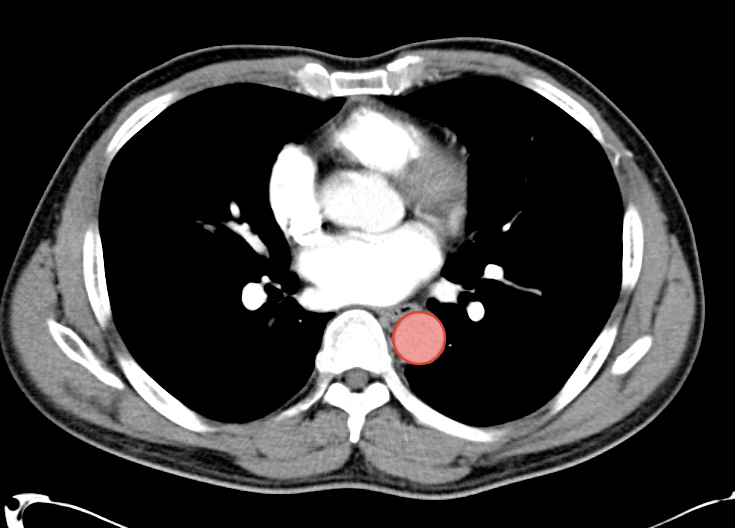

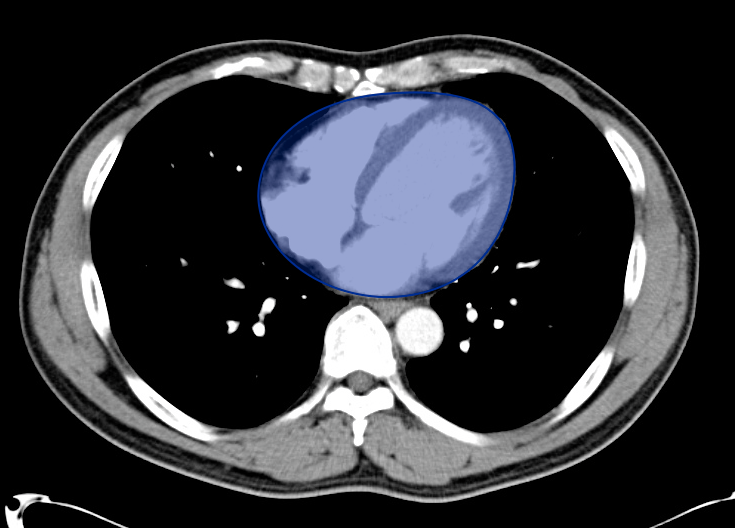

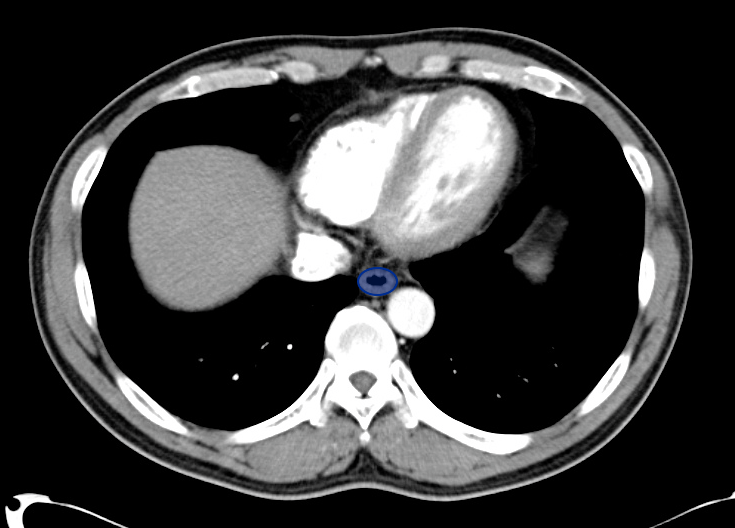

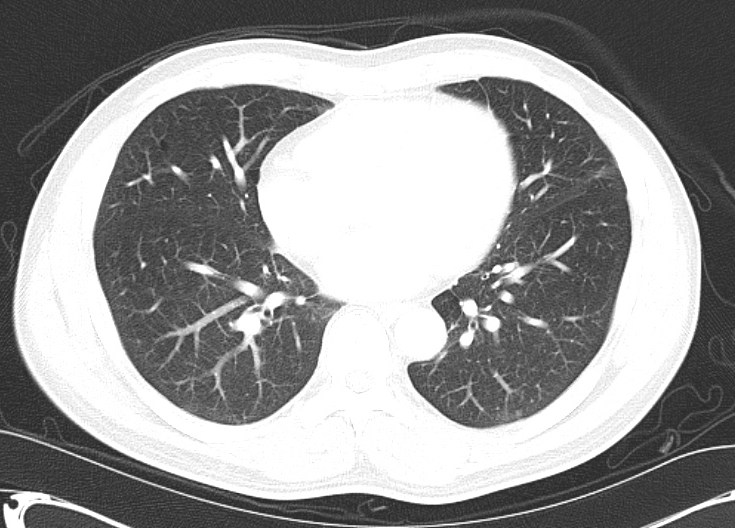

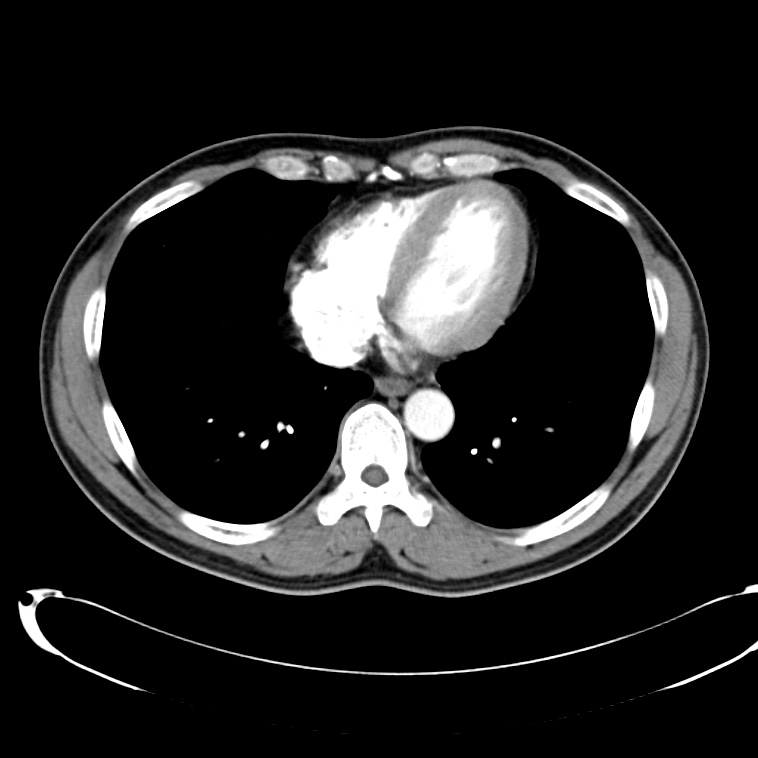

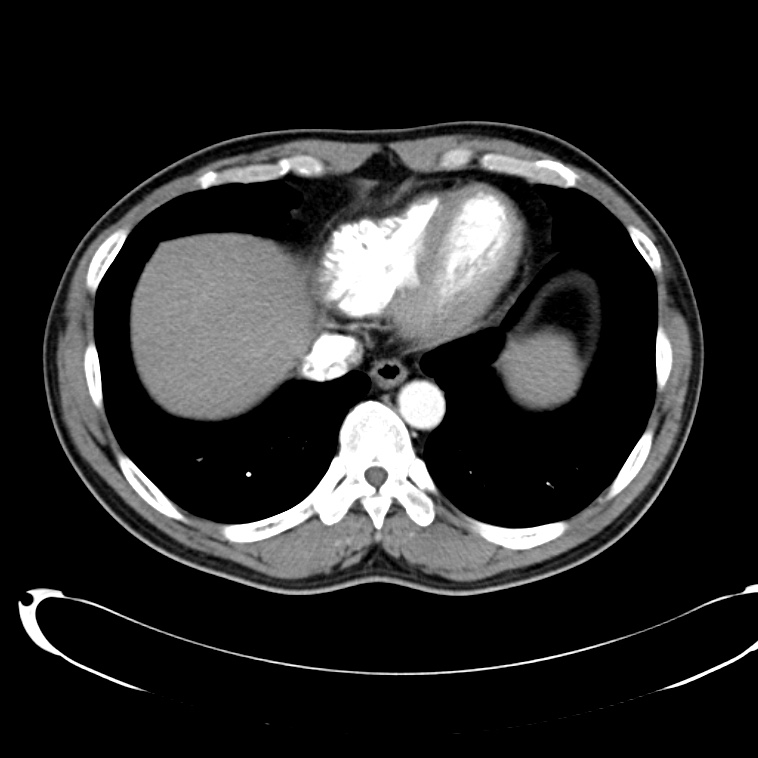

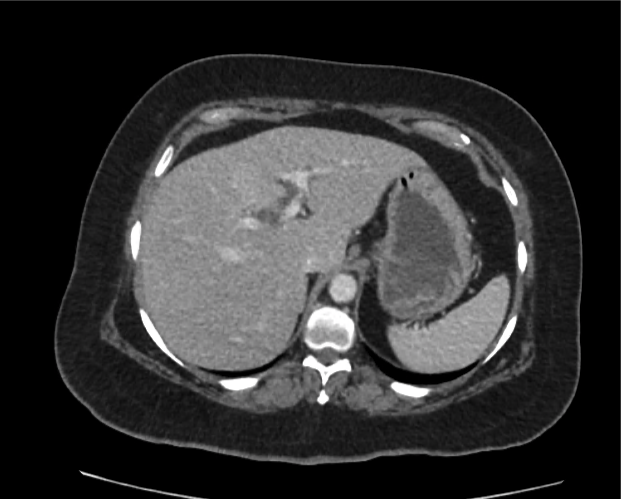

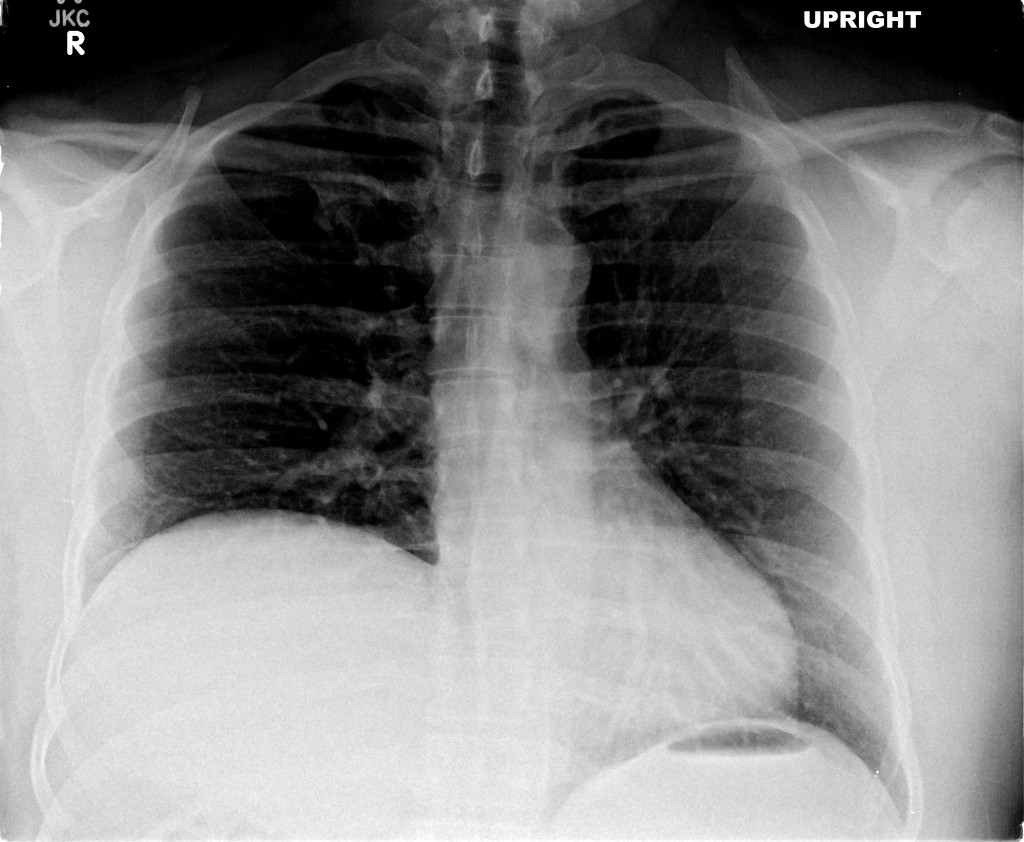

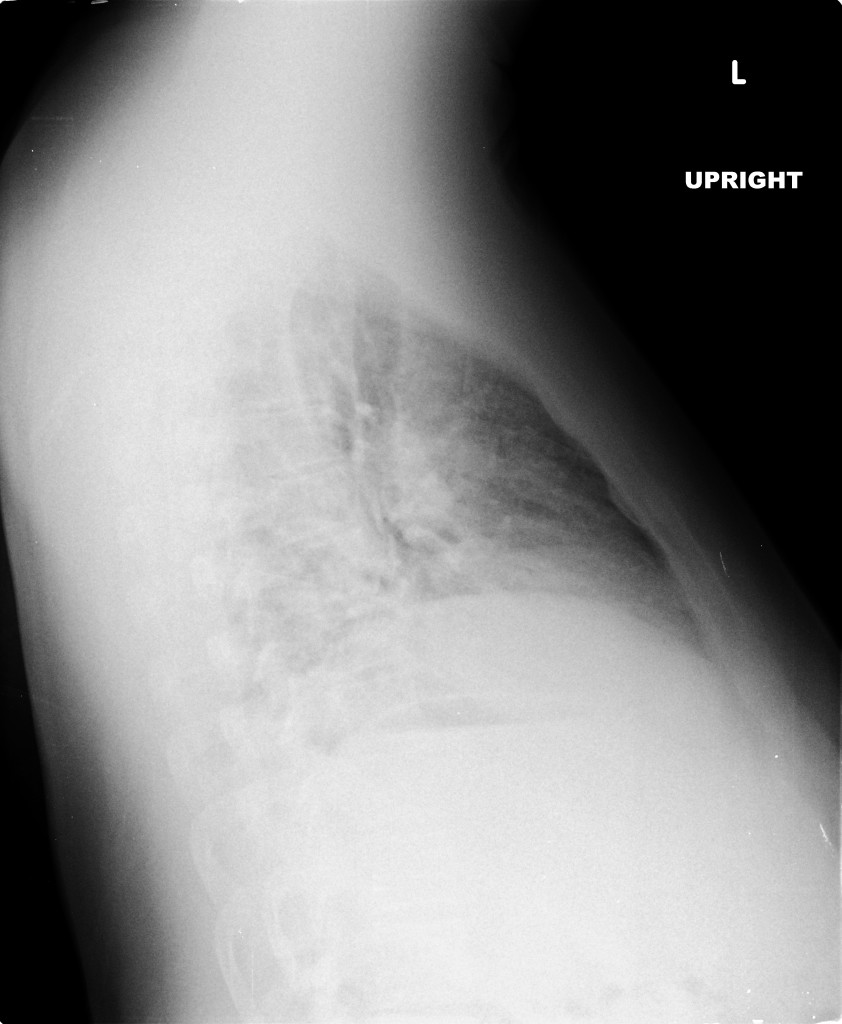

CT Pulmonary Angiography:

No evidence of central pulmonary embolism, thoracic aortic dissection, or thoracic aortic aneurysm. Evaluation of the peripheral vessels is limited due to motion artifact. No focal consolidation or pneumothorax.

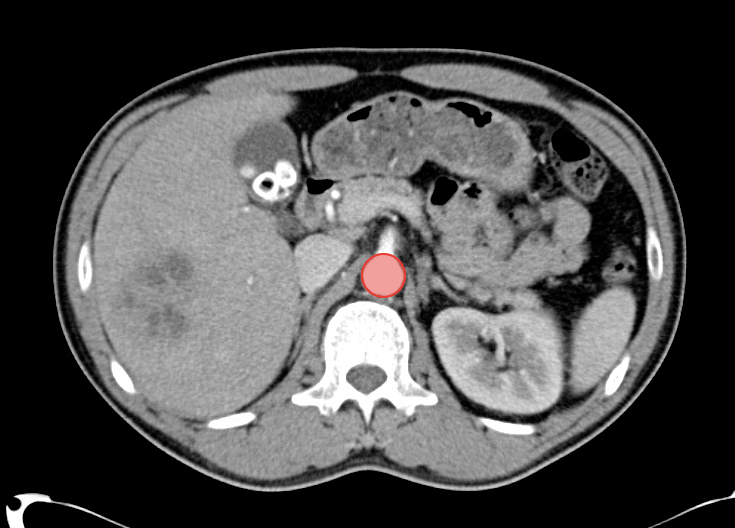

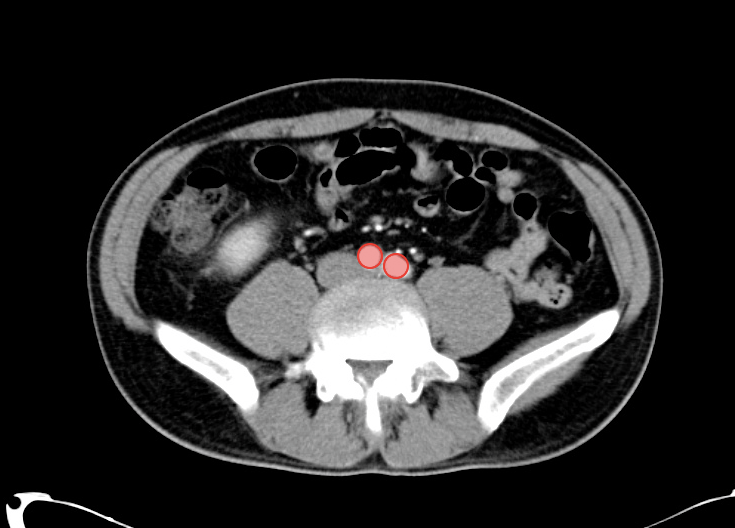

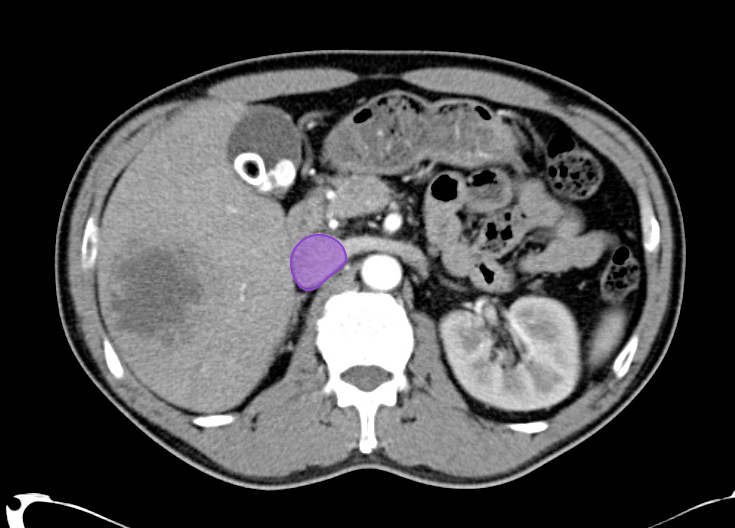

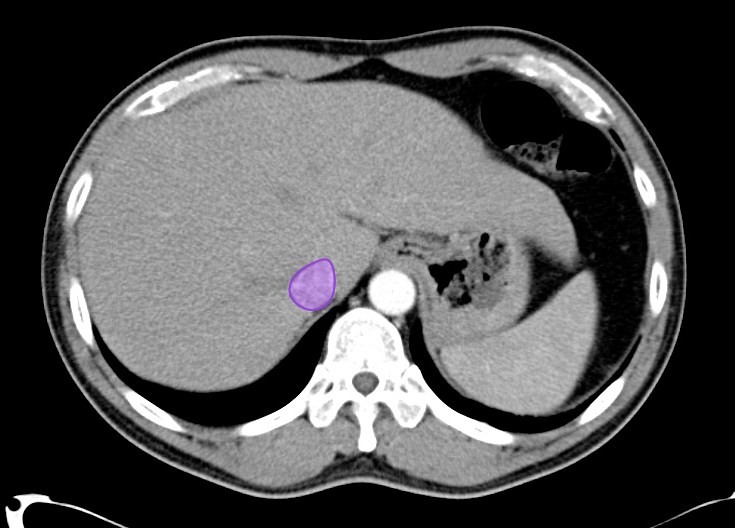

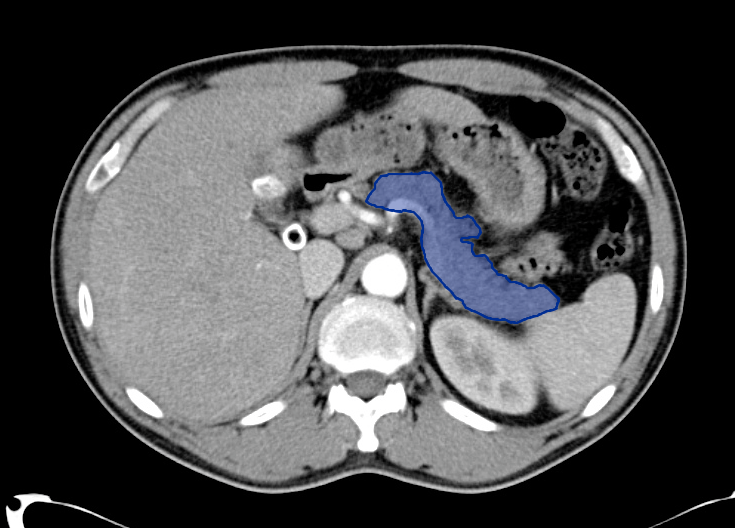

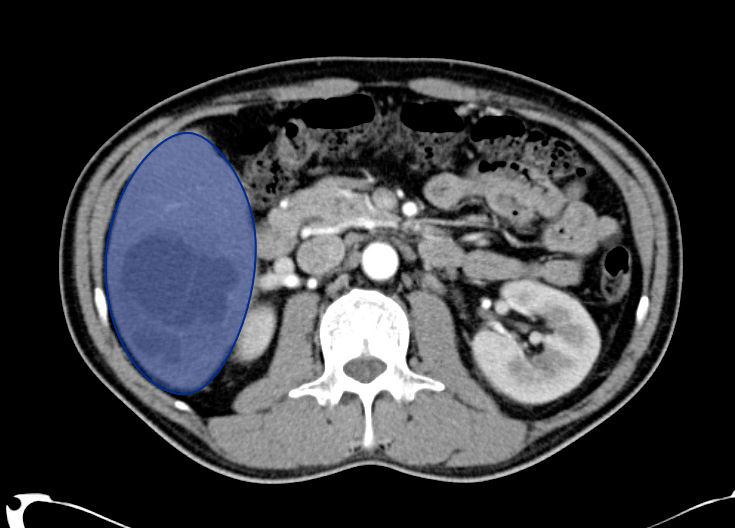

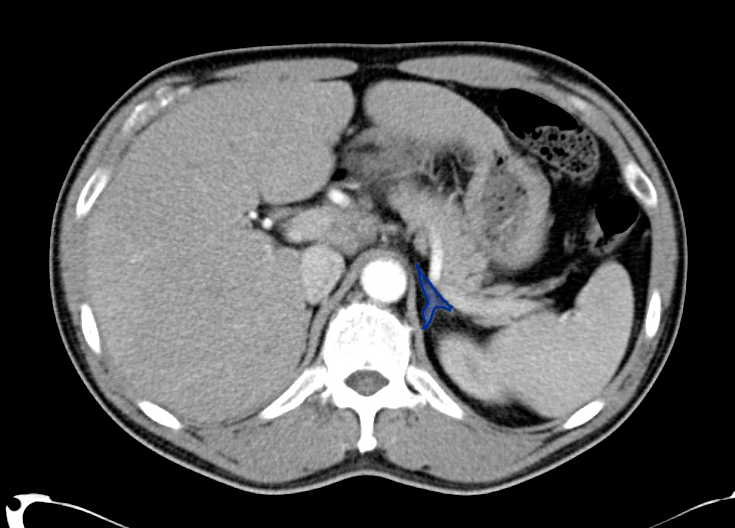

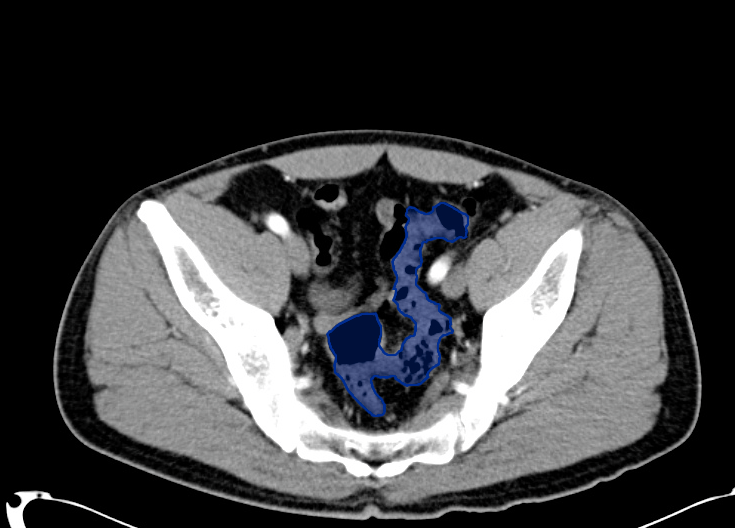

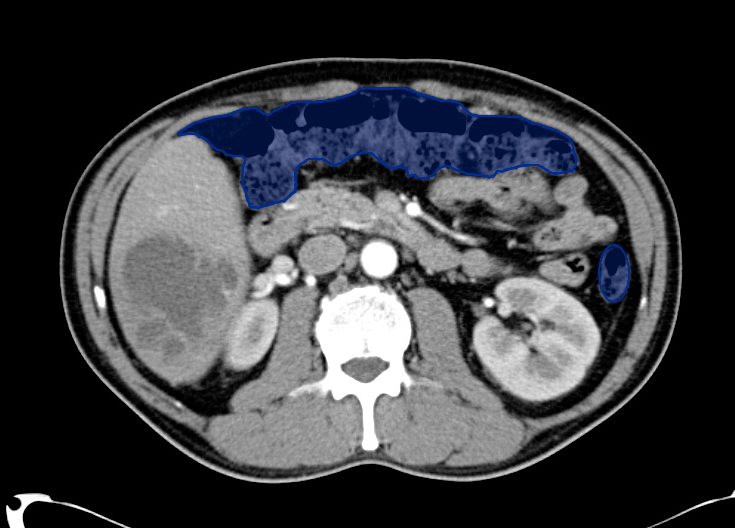

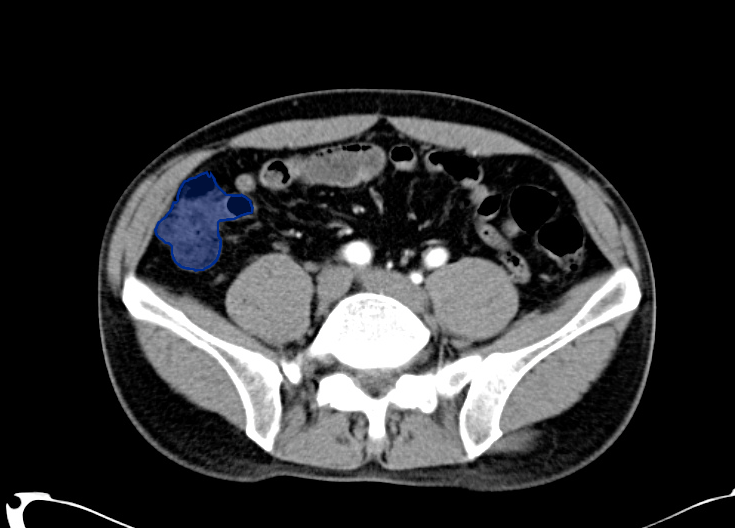

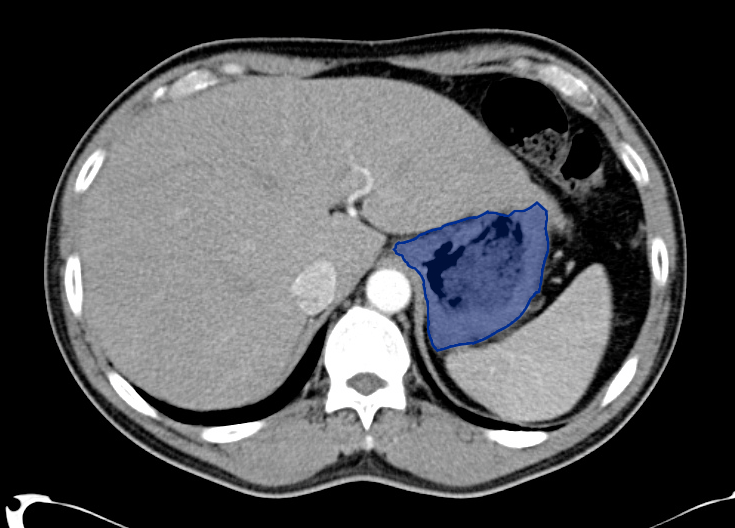

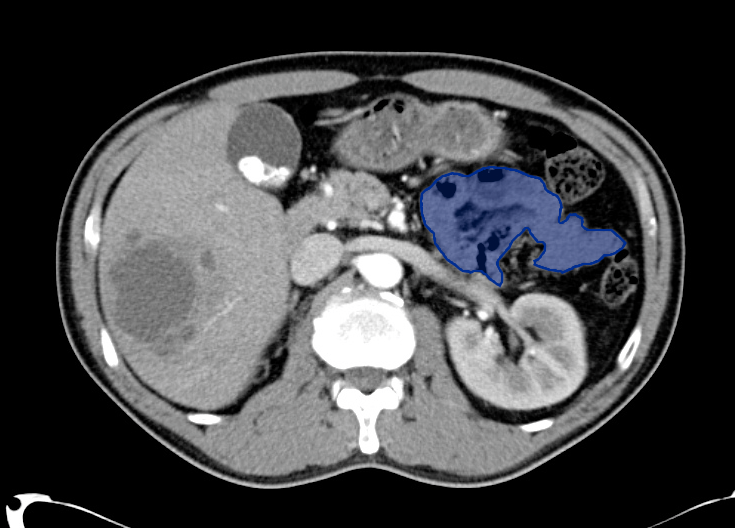

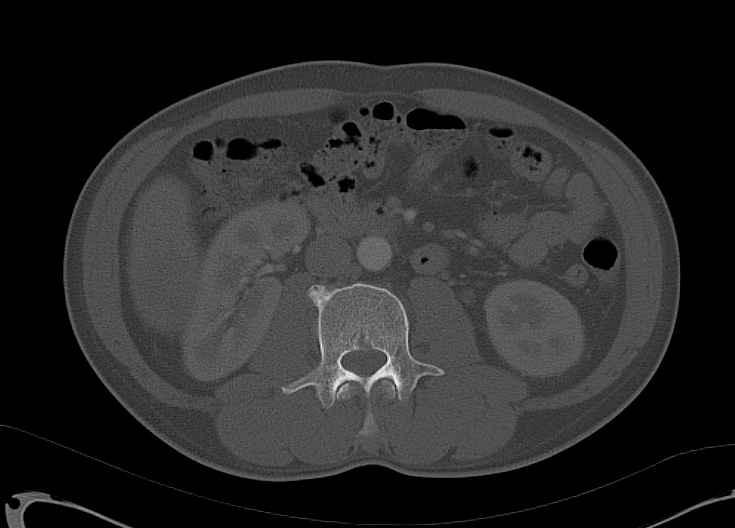

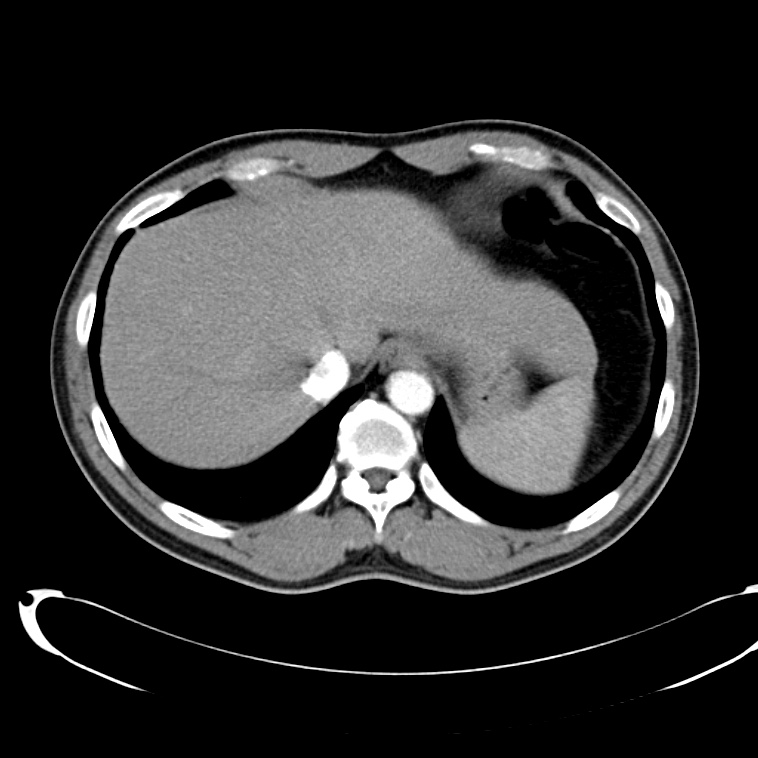

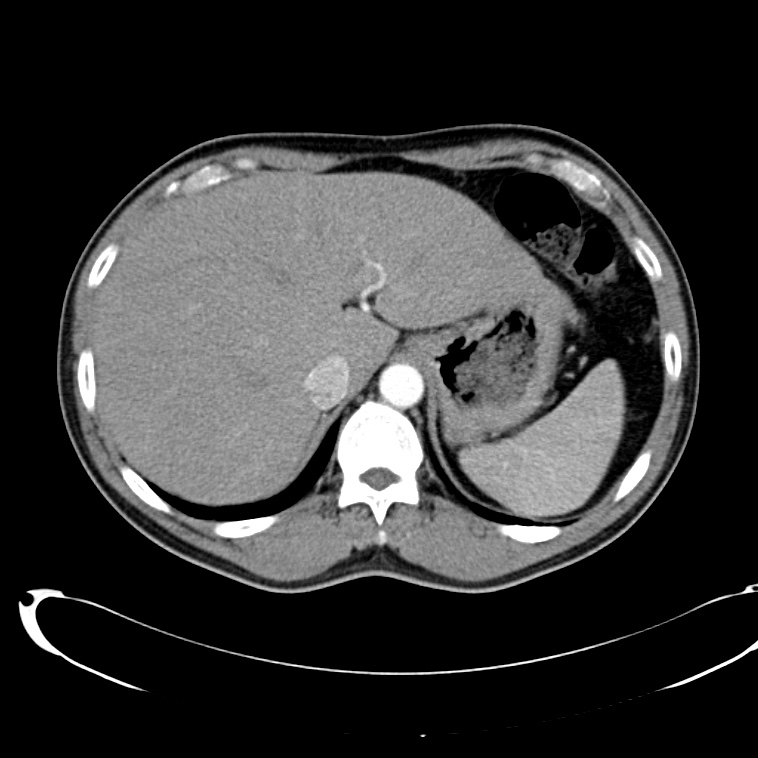

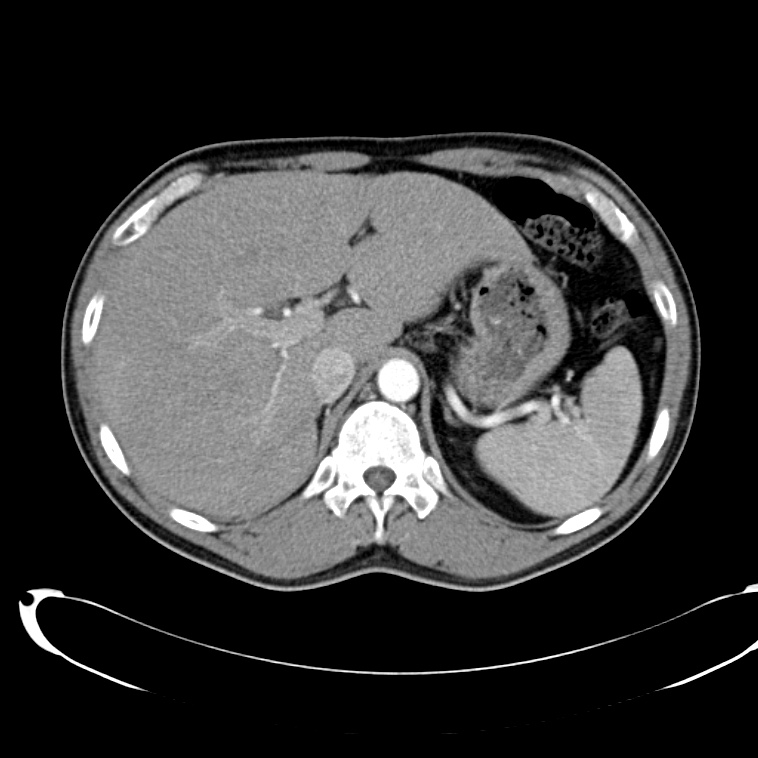

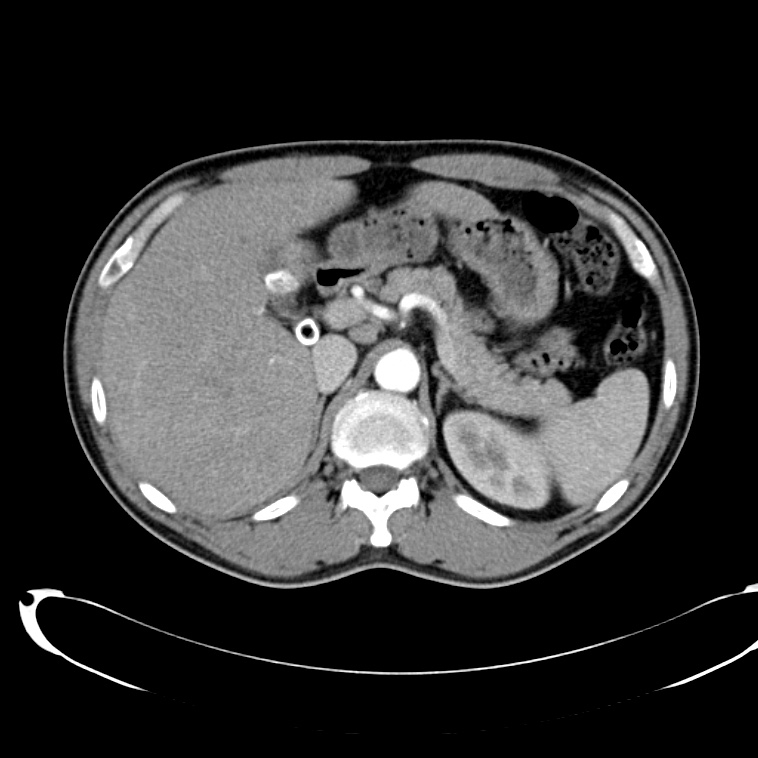

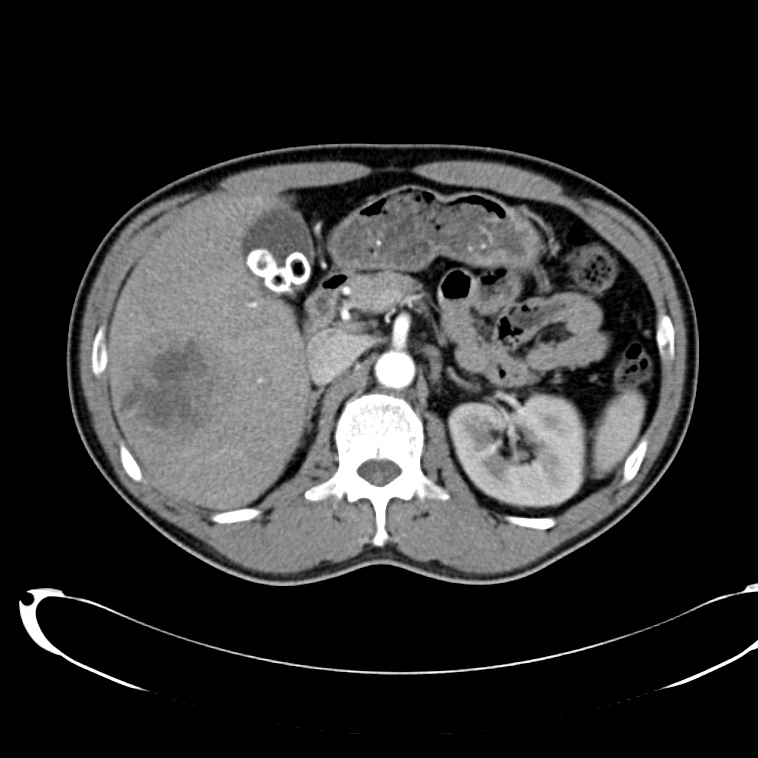

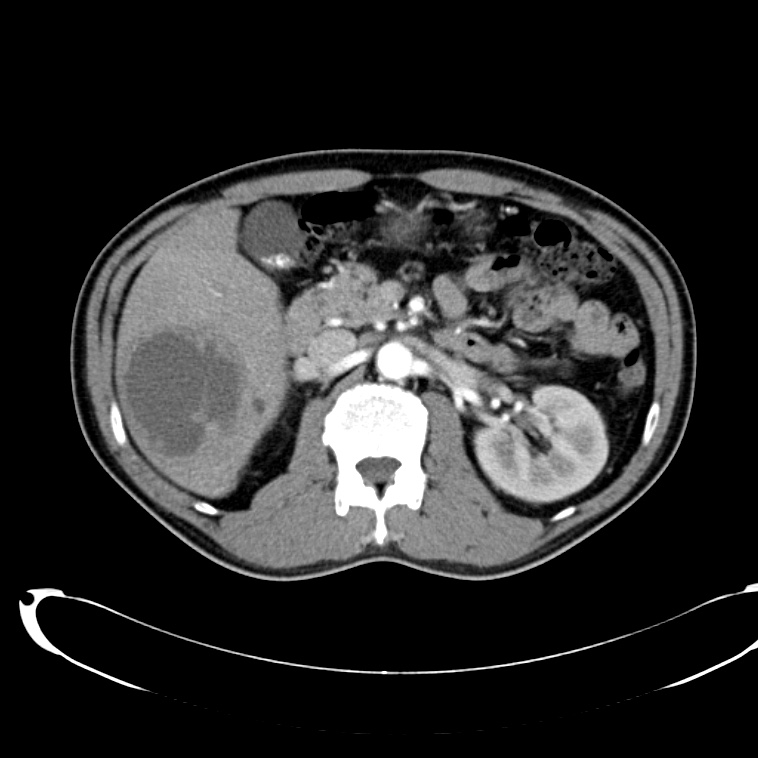

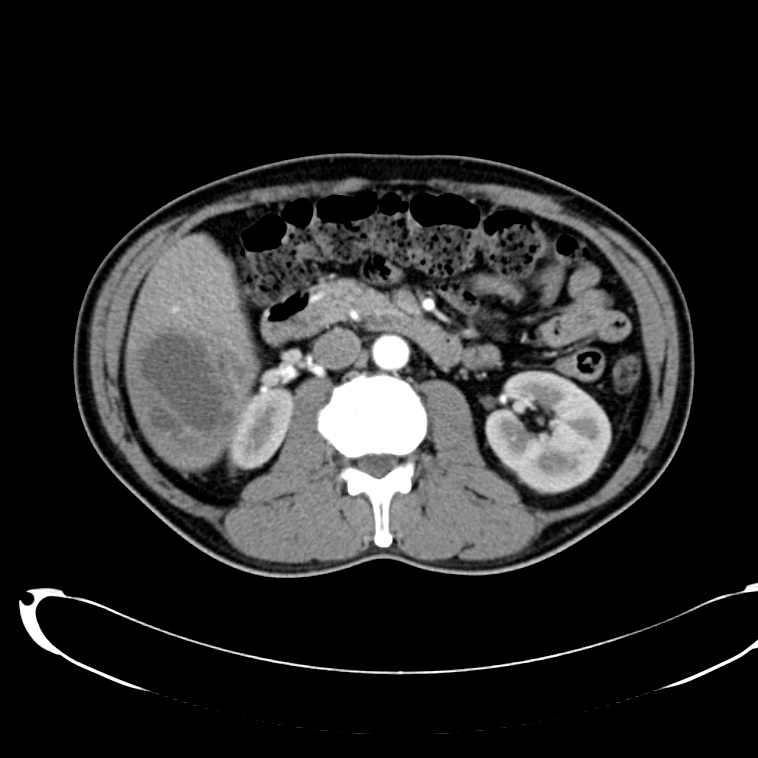

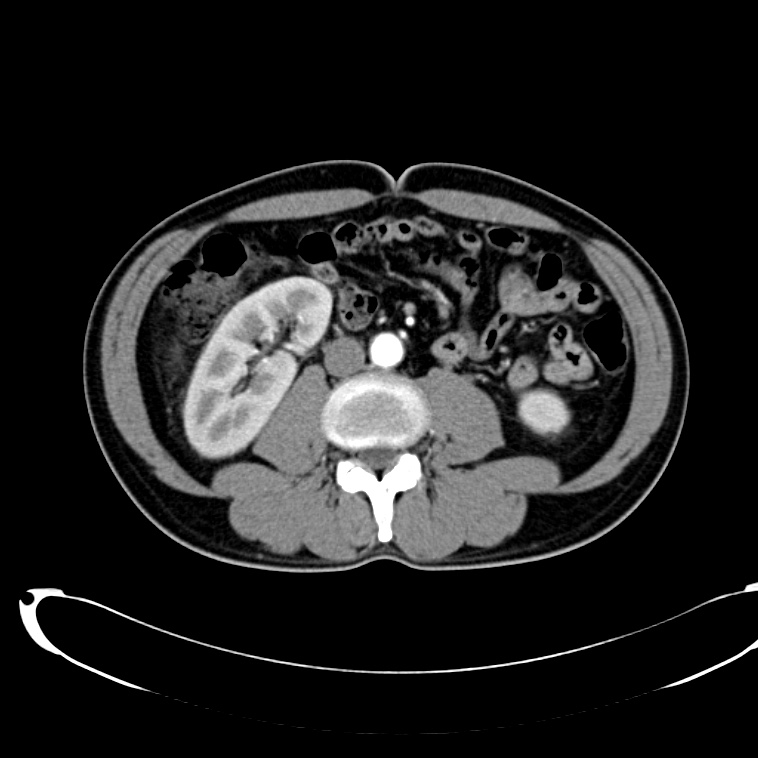

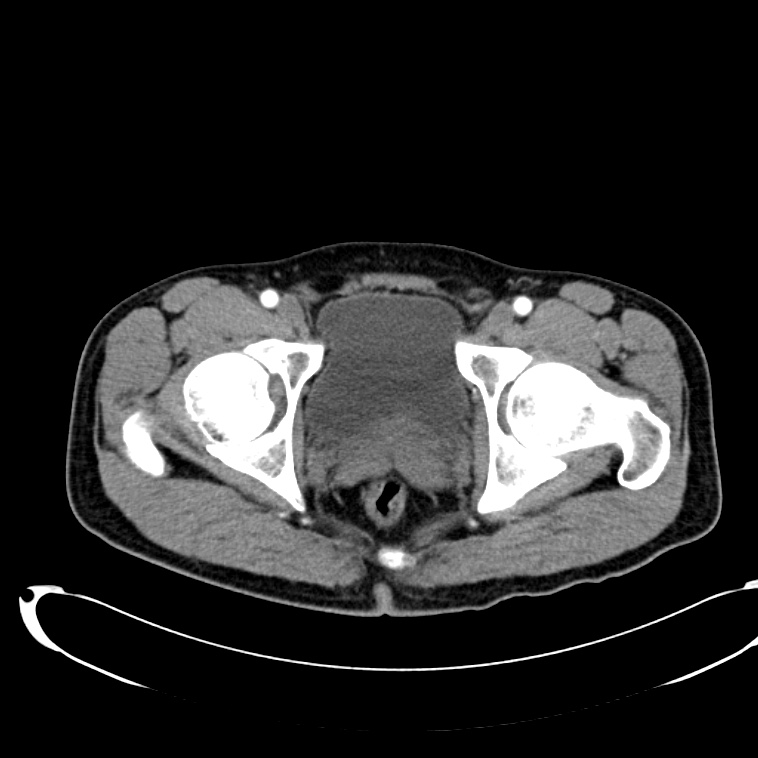

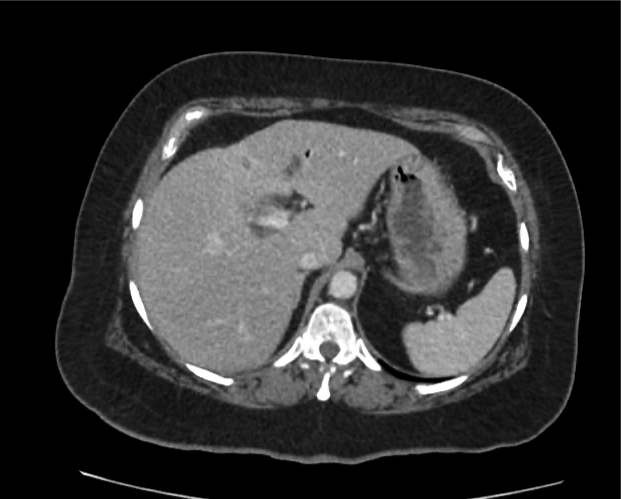

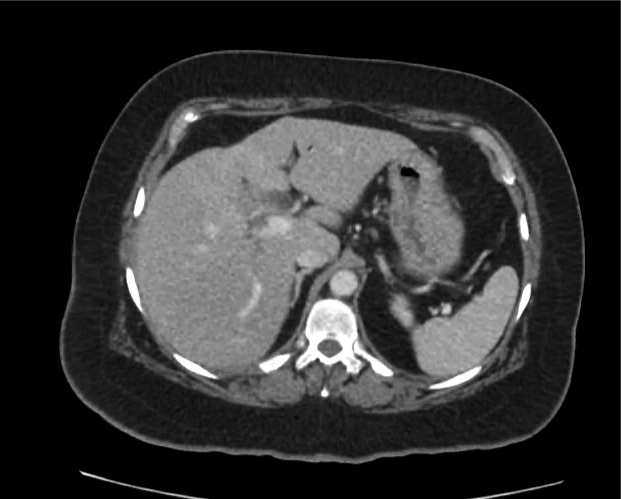

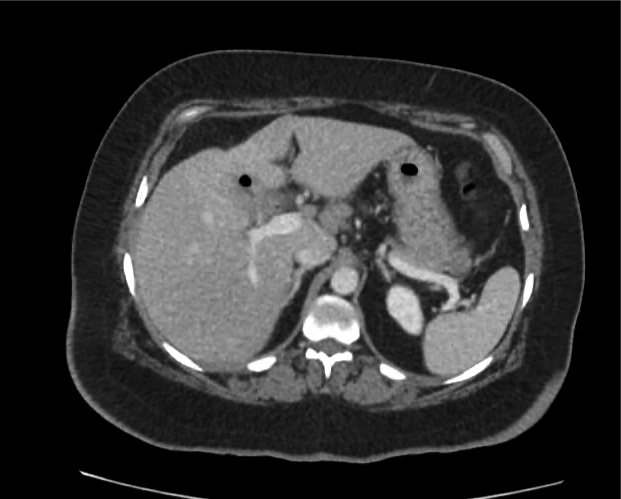

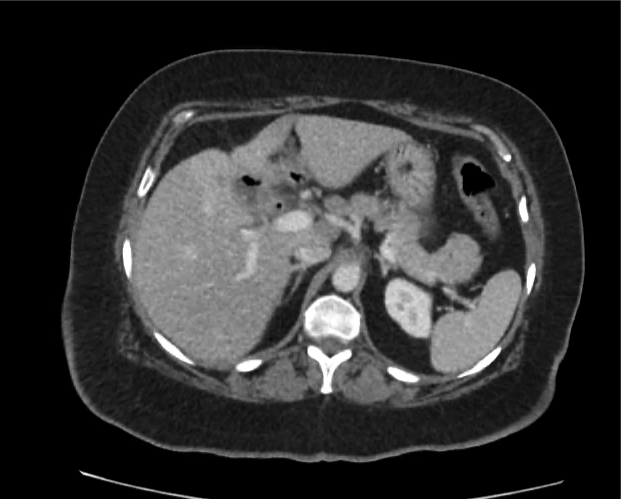

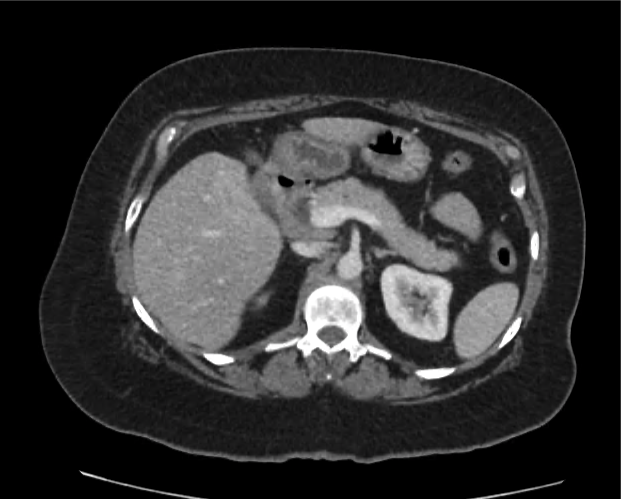

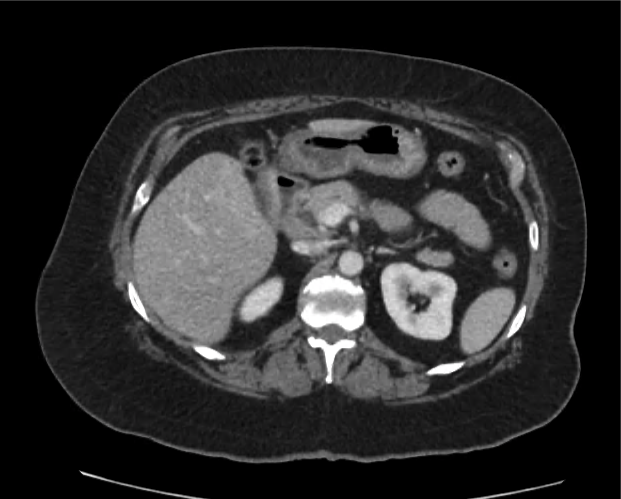

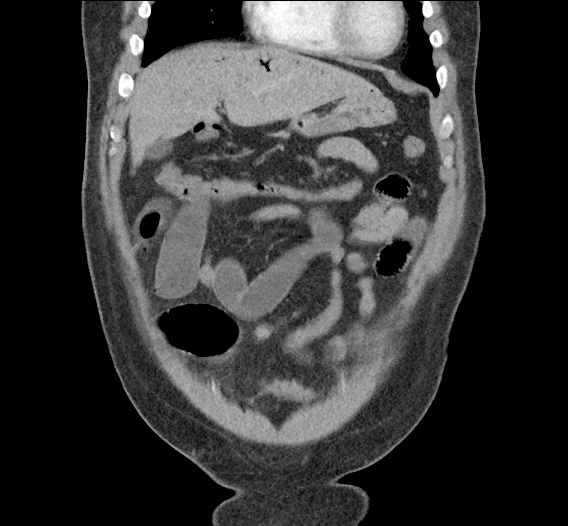

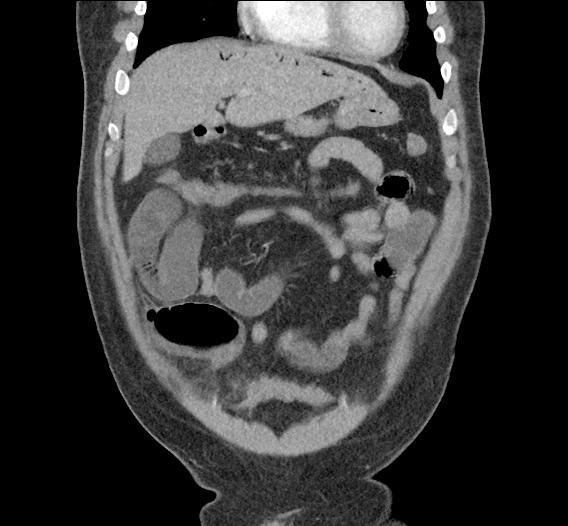

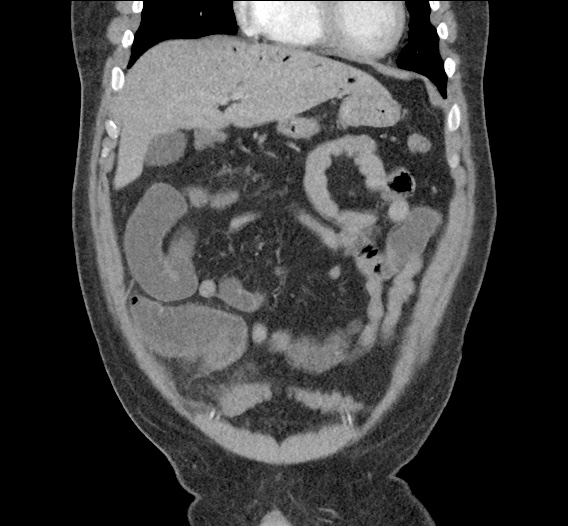

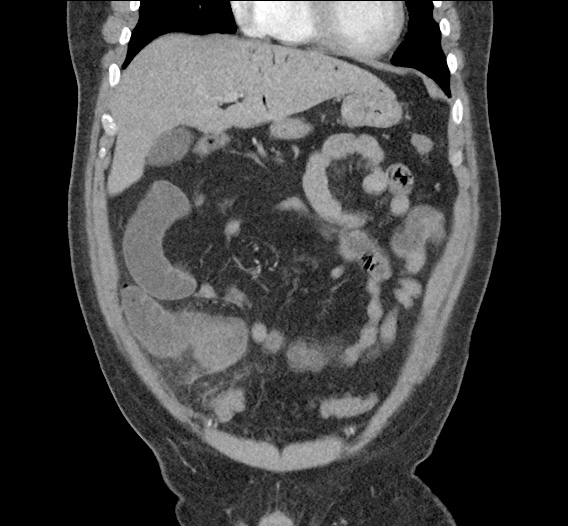

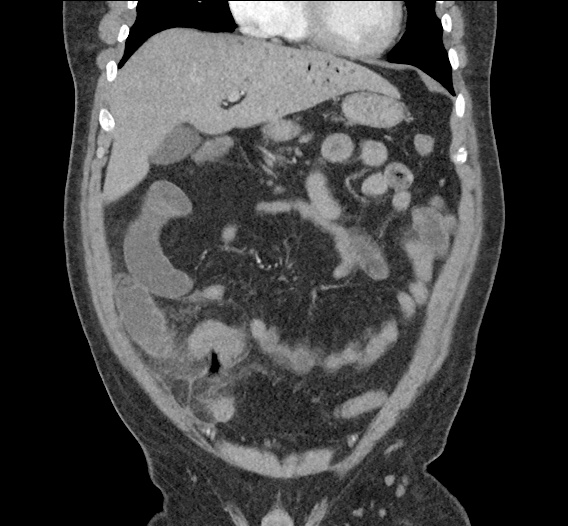

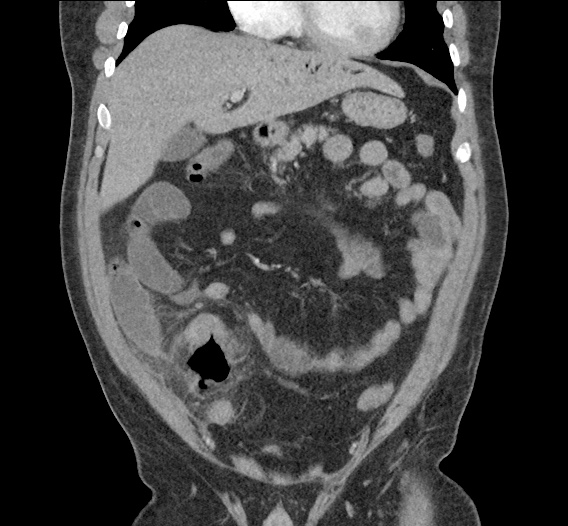

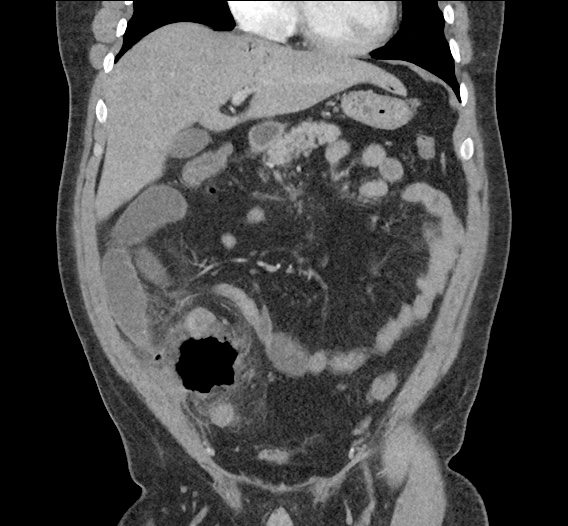

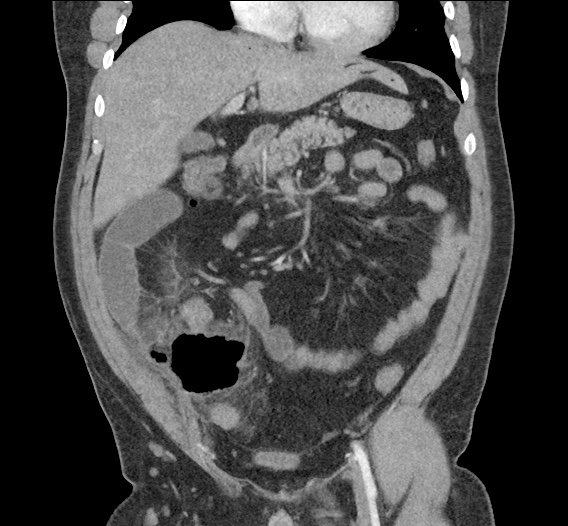

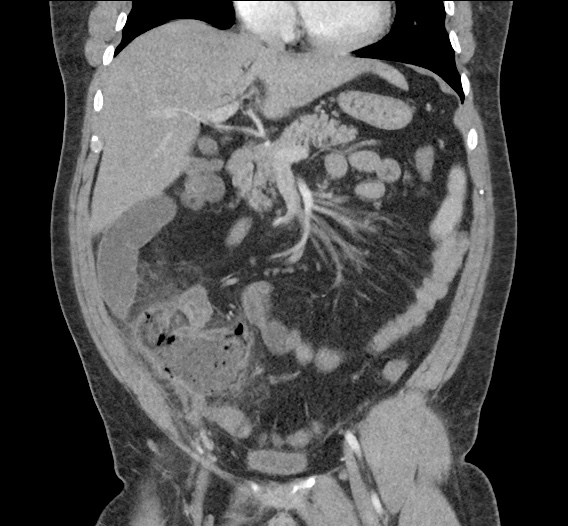

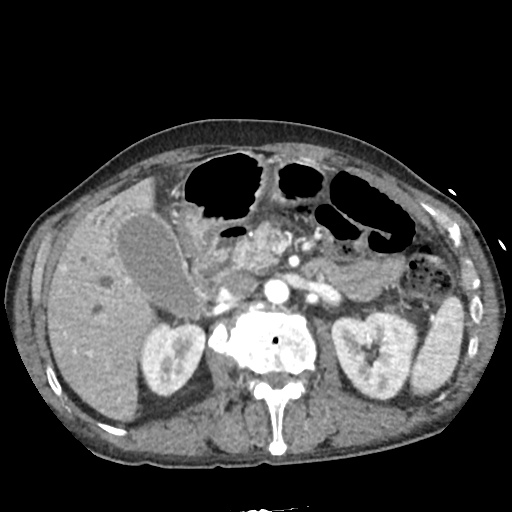

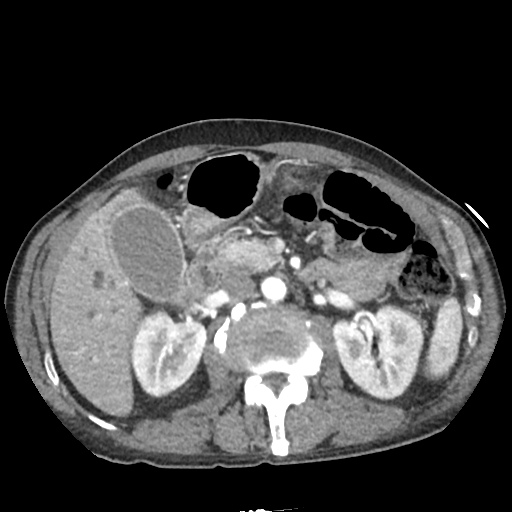

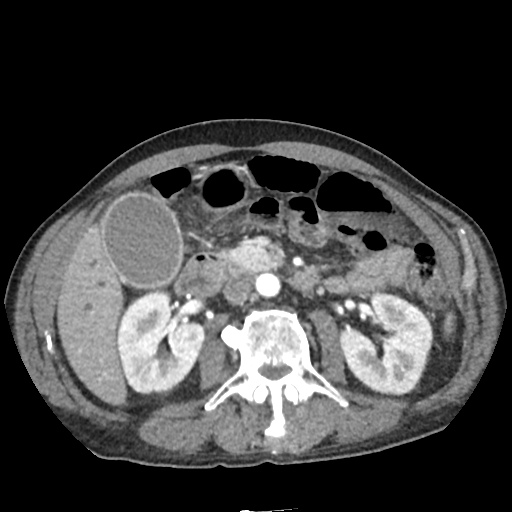

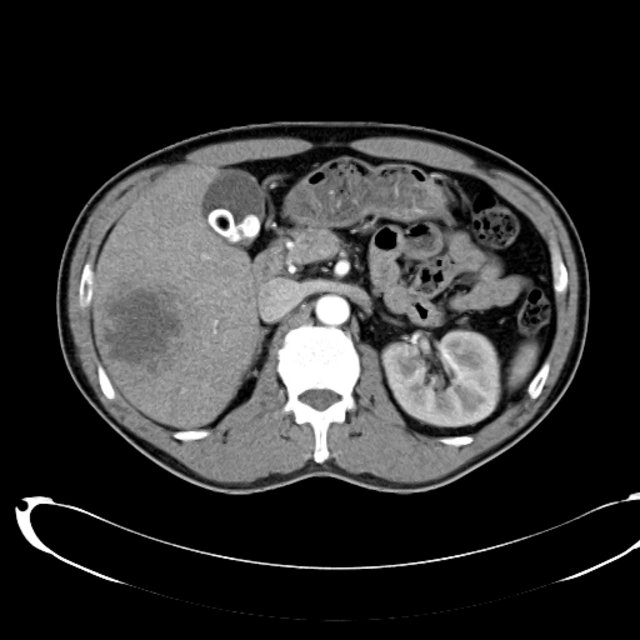

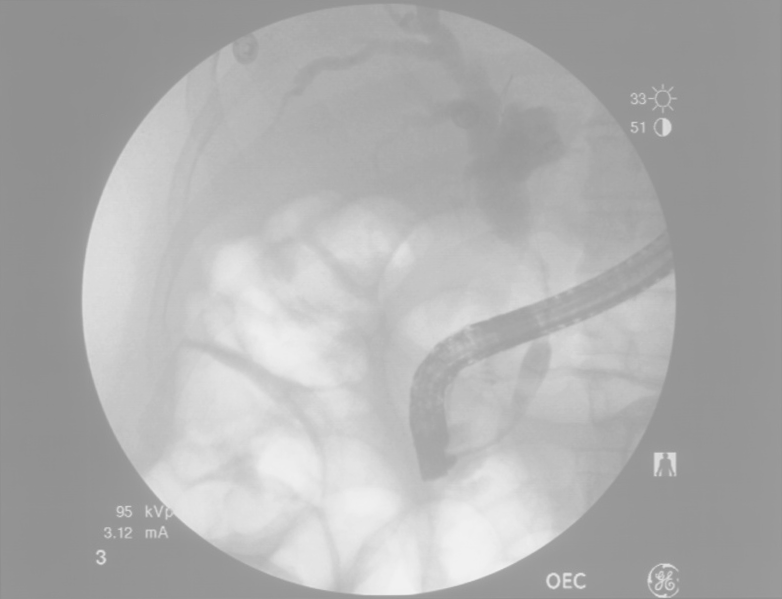

CT Abdomen/Pelvis non-contrast:

No evidence of intra-abdominal abscess or definite source of infection. Marked hepatic steatosis.

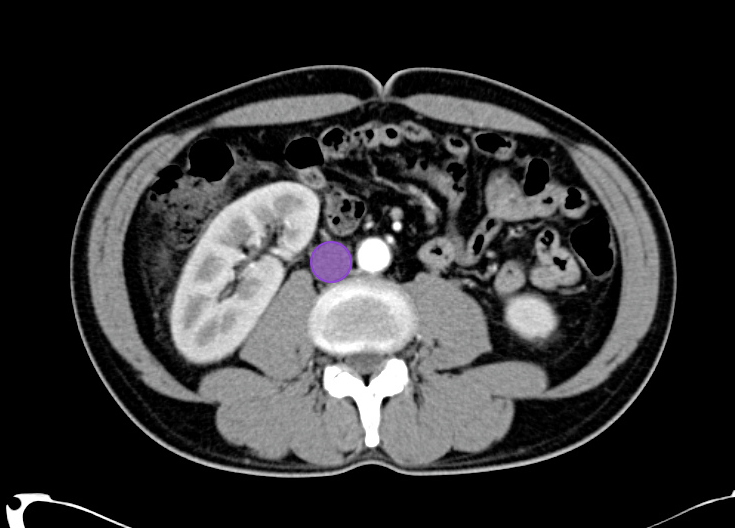

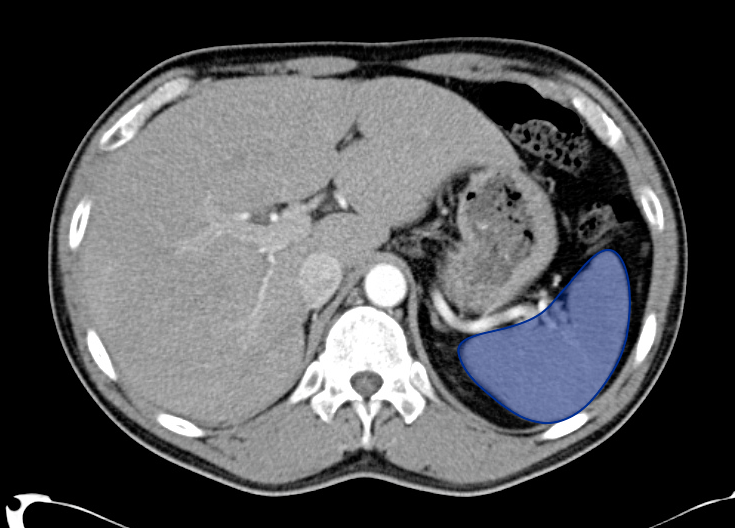

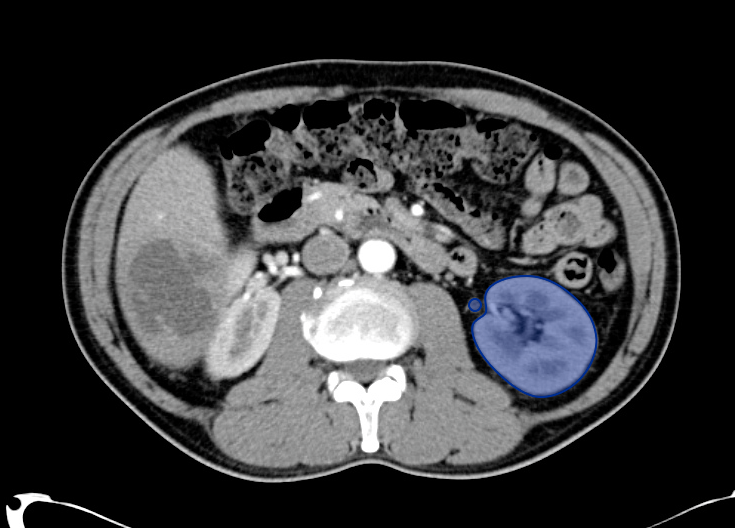

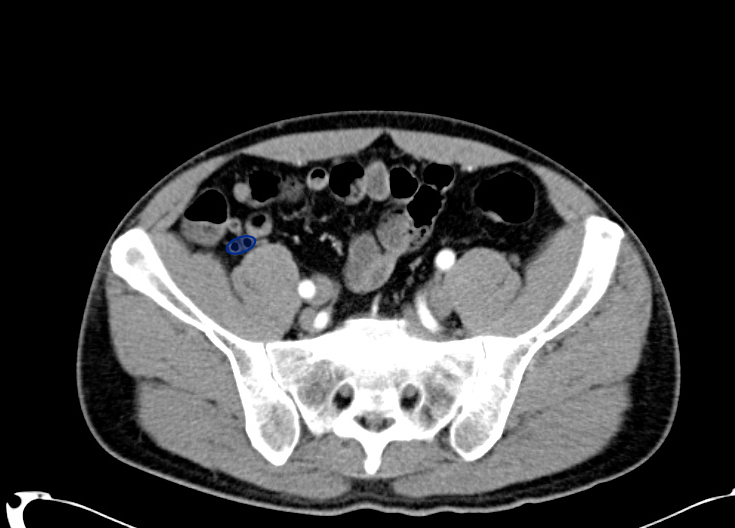

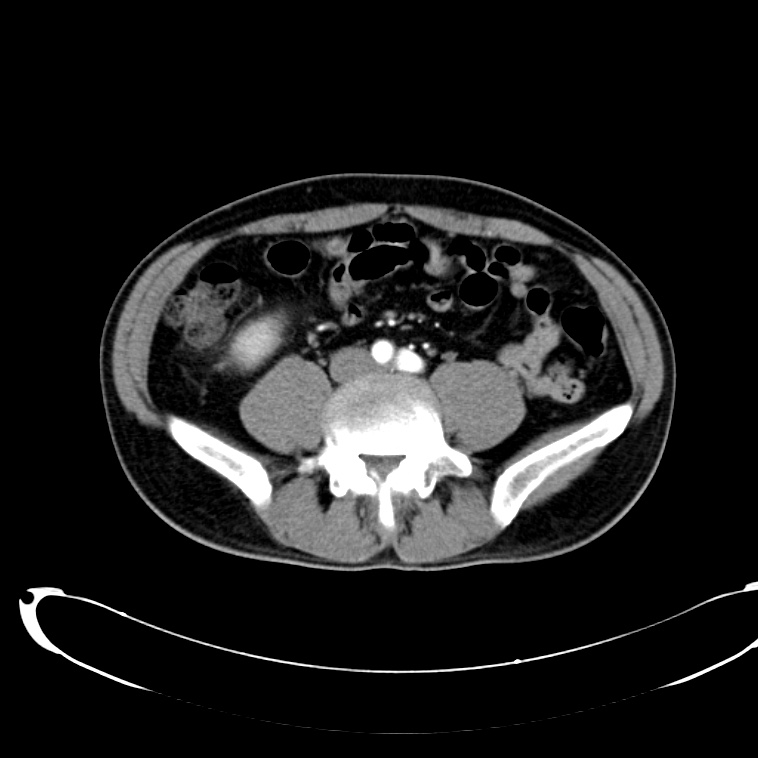

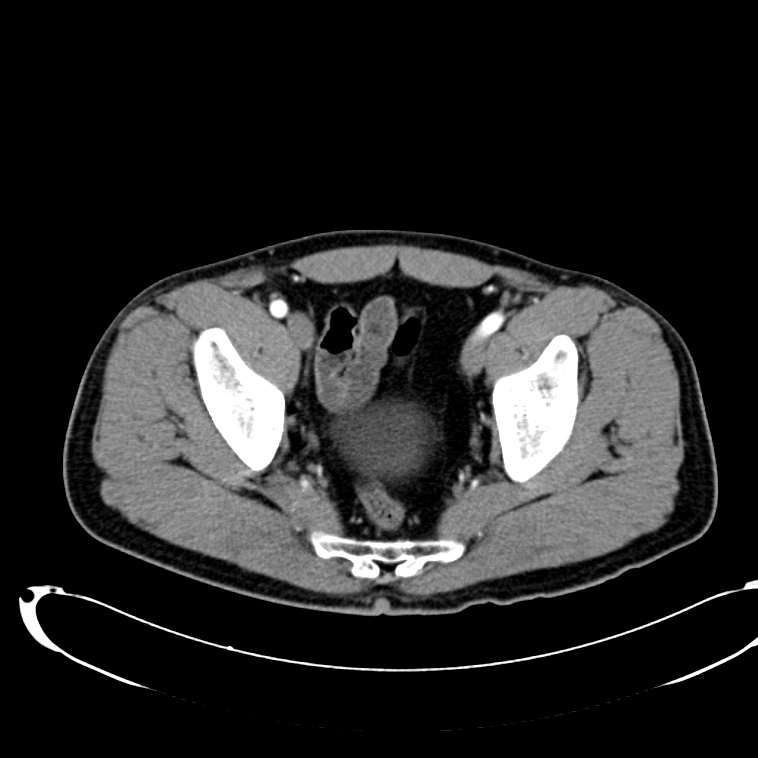

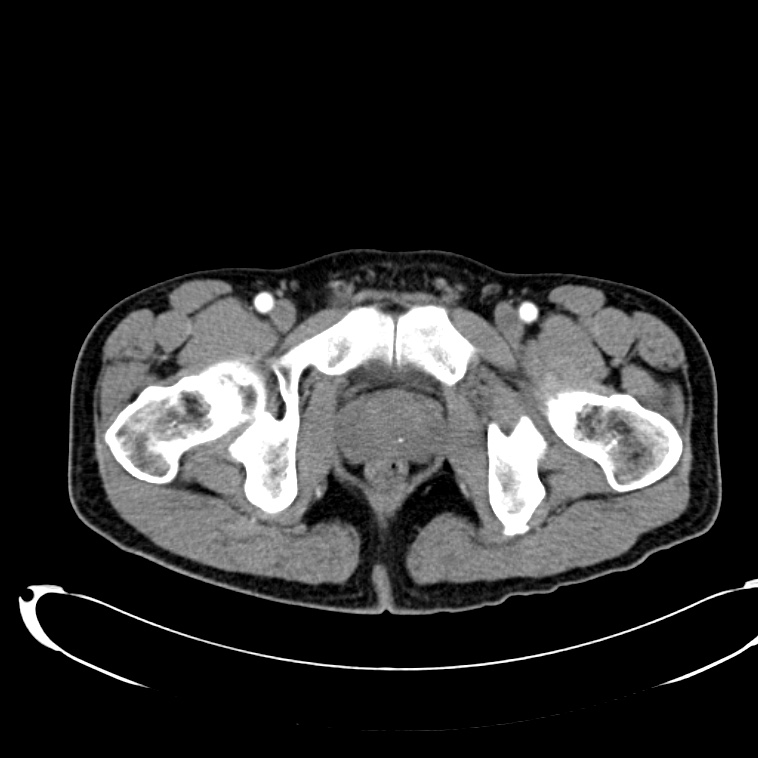

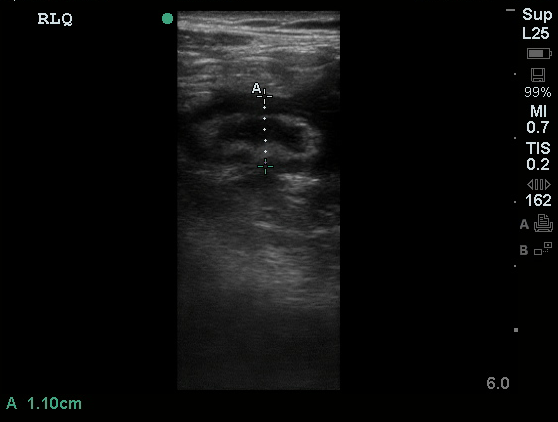

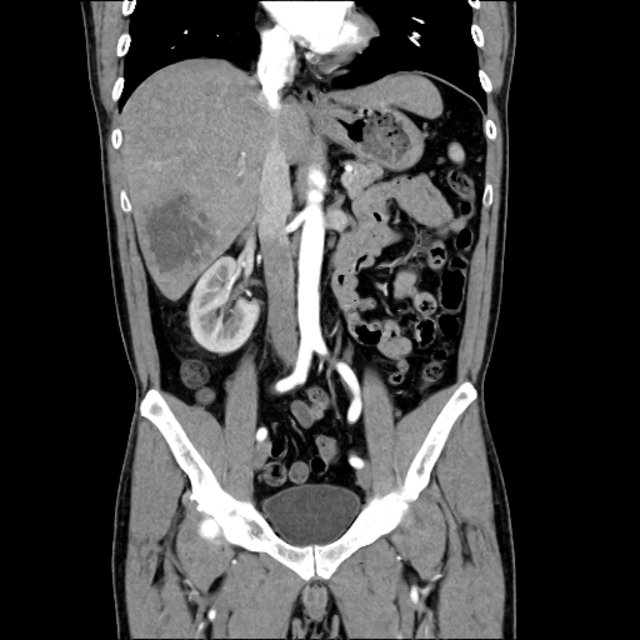

CT Lower Extremity non-contrast:

Diffuse circumferential subcutaneous edema involving both lower extremities from the level of the mid thighs distally through the feet. There are bilateral subcutaneous calcifications which are likely venous calcifications in the setting of chronic venous stasis disease. There is some overlying skin thickening.

TTE:

There is moderate concentric left ventricular hypertrophy with hyperdynamic LV wall motion. The Ejection Fraction estimate is >70%. Grade I/IV (mild) LV diastolic dysfunction. No hemodynamically significant valve abnormalities.

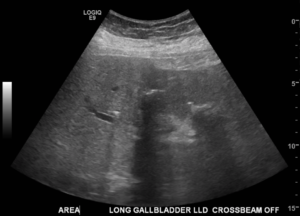

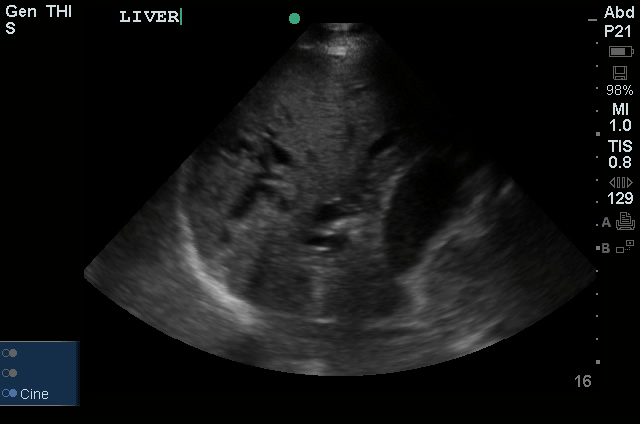

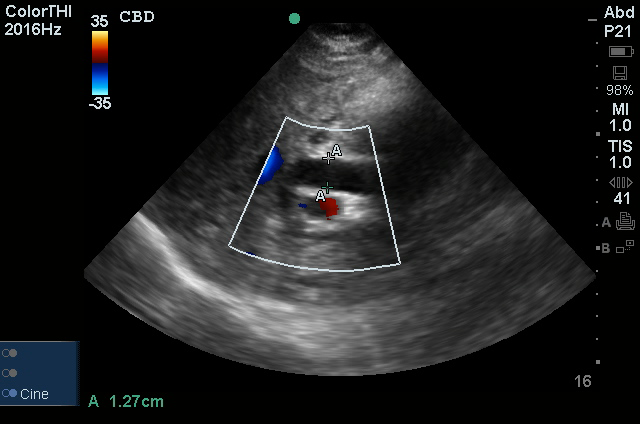

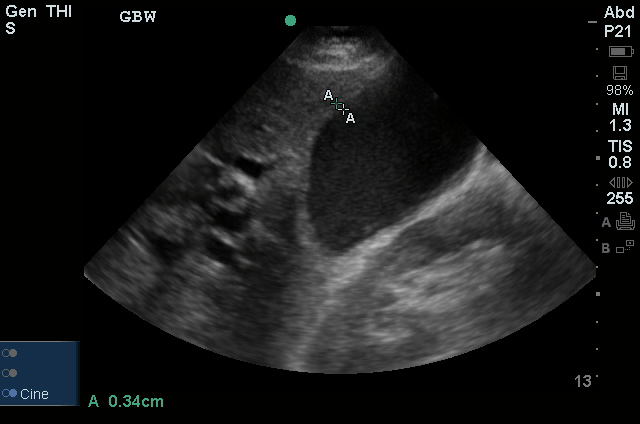

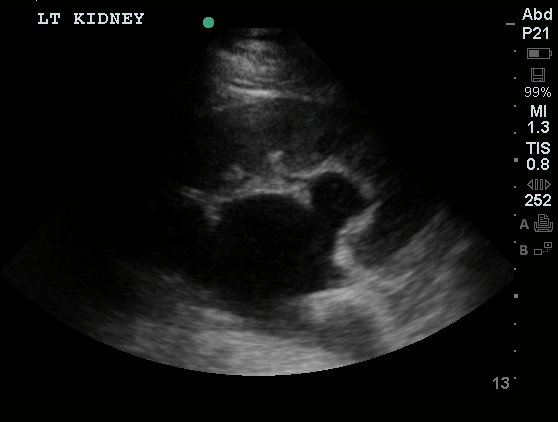

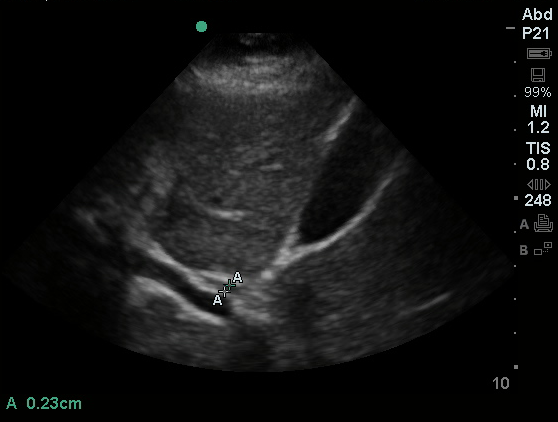

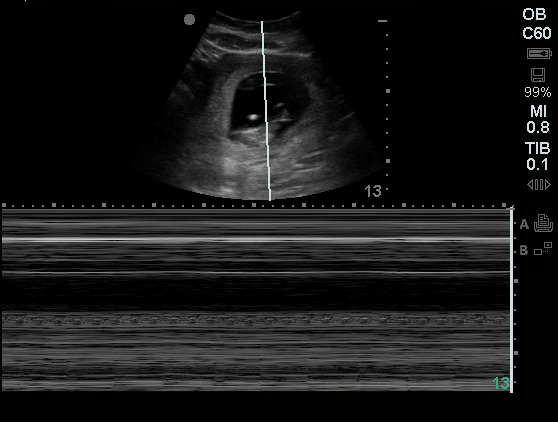

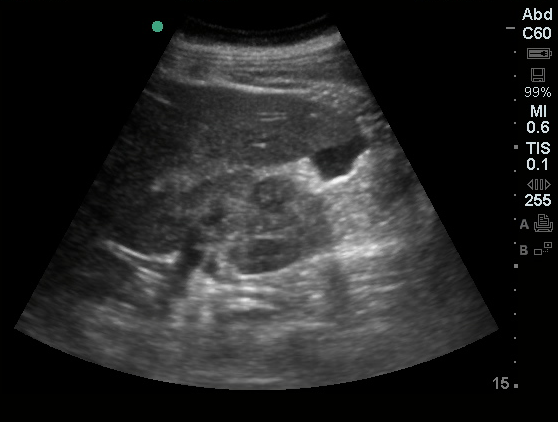

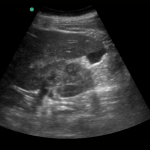

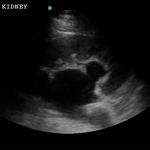

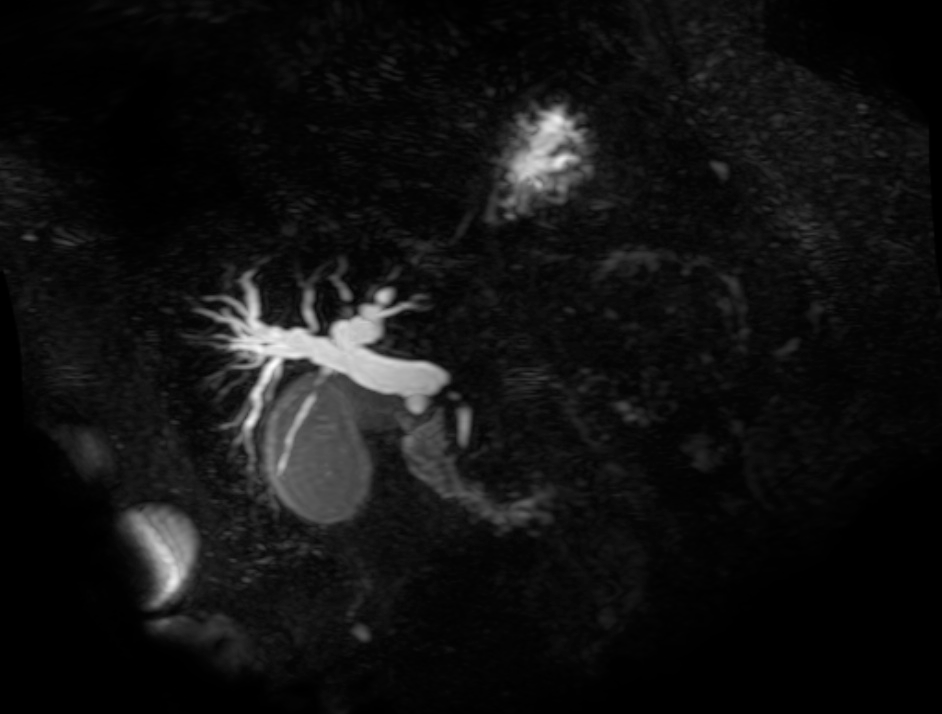

US Abdomen:

Hepatomegaly, echogenic liver suggesting fatty infiltration. Moderately blunted hepatic vein waveforms suggesting decreased hepatic parenchymal compliance.

Assessment/Plan:

The patient was admitted to the cardiology service for management of NSTEMI and evaluation of undiagnosed CHF. She was started on a heparin continuous infusion. In addition, a CT pulmonary angiogram was obtained to evaluate for pulmonary embolism as an explanation of her progressive dyspnea on exertion. No PE, consolidation or effusion was identified.

Despite the patient’s reported history of congestive heart failure, there was no evidence that her symptoms were a result of an acute exacerbation with only a mildly elevated BNP but no jugular venous distension or evidence of pulmonary edema. The patient’s significant lower extremity edema was more suggestive of chronic venous stasis.

One notable laboratory abnormality that was explored was her elevated anion gap metabolic acidosis. Studies submitted included serum lactate, salicylates, osmolarity, CK, and urinalysis for ketonuria. This evaluation was notable for an elevated serum lactate of 13.2mmol/L and an arterial blood gas that showed adequate respiratory compensation (and no A-a gradient). Given the patient’s modest leukocytosis (with neutrophil predominance), and tachycardia, the concern for sepsis was increased though the source remained unclear. Prominent possibilities included a skin and soft-tissue infection vs. less likely intra-abdominal source though the patient’s physical examination was not suggestive of a process that would produce such a substantial lactic acidosis. Blood cultures were drawn and the patient was started on empiric antibiotics for the suspected sources. In addition, the patient was cautiously volume resuscitated given her reported history of CHF while pending a transthoracic echocardiogram to evaluate cardiac function. Additional imaging including CT abdomen/pelvis and lower extremities was obtained (though without contrast due to the patient’s recent exposure), and no obvious source was identified.

Over the next two days, the patient’s serum lactate downtrended to normal range, as did the serum troponin. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed an LVEF >70% with mild concentric hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction. Blood and urine cultures were without growth.

Additional issues managed during the hospitalization included elevated serum transaminases (AST > ALT), conjugated hyperbilirubinemia and evidence of decreased hepatic synthetic function with hypoalbuminemia and elevated INR. Given the patient’s history of EtOH use, as well as other corroborating findings including macrocytic anemia, hypomagnesemia, folate and B12 deficiency, this was attributed to alcoholic hepatitis (discriminant function <32). Infectious hepatitis serologies were negative. The patient was started on nutritional supplements.

Finally, the patient persistently complained of lip and oral mucosal pain. Examination was without discrete lesions but some mucosal redness was identified. Despite poor dentition, there was no evidence of abscess and HSV/HIV testing was negative. This was thought to be stomatitis caused by her identified nutritional deficiencies.

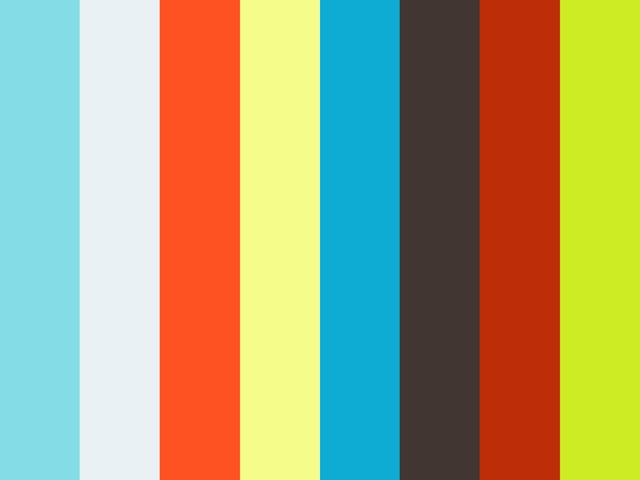

Differential Diagnosis of Elevated Serum Lactate 1,2

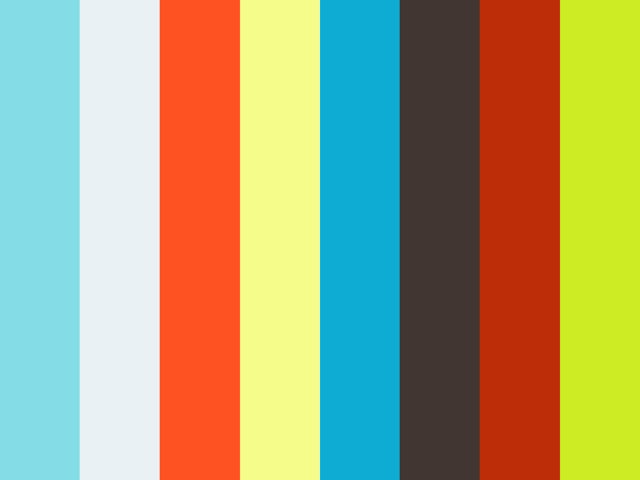

Algorithm for Evaluation of Acidemia 3,4

Algorithm for Evaluation of Alkalemia 3,4

References:

- Fall, P. J., & Szerlip, H. M. (2005). Lactic acidosis: from sour milk to septic shock. Journal of intensive care medicine, 20(5), 255–271. doi:10.1177/0885066605278644

- Luft, F. C. (2001). Lactic acidosis update for critical care clinicians. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN, 12 Suppl 17, S15–9.

- Ingelfinger, J. R., Berend, K., de Vries, A. P. J., & Gans, R. O. B. (2014). Physiological Approach to Assessment of Acid–Base Disturbances. The New England journal of medicine, 371(15), 1434–1445. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1003327

- Ingelfinger, J. R., & Seifter, J. L. (2014). Integration of Acid–Base and Electrolyte Disorders. The New England journal of medicine, 371(19), 1821–1831. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1215672