Brief HPI:

An overhead page alerts you to an arriving patient with cardiac arrest. An approximately 35-year-old male was running away from police officers and collapsed after being shot with a stun gun. The patient was found to be pulseless, CPR was started by police officers and the patient is en route.

An Algorithm for the Evaluation and Management of Cardiac Arrest with Ultrasonography

Causes of Cardiac (and non-cardiac) Arrest

Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) leading to sudden cardiac death (SCD) if not successfully resuscitated, refers to the unexpected collapse of circulatory function. Available epidemiologic data for in-hospital and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) point appropriately to cardiac processes as the most common cause, though extra-cardiac processes (most frequently respiratory), comprise up to 40% of cases1-3.

Identifying the underlying cause is critical as several reversible precipitants require rapid identification. However, the usual diagnostic techniques may be challenging, limited or absent – including patient history, detailed examination, and diagnostic studies.

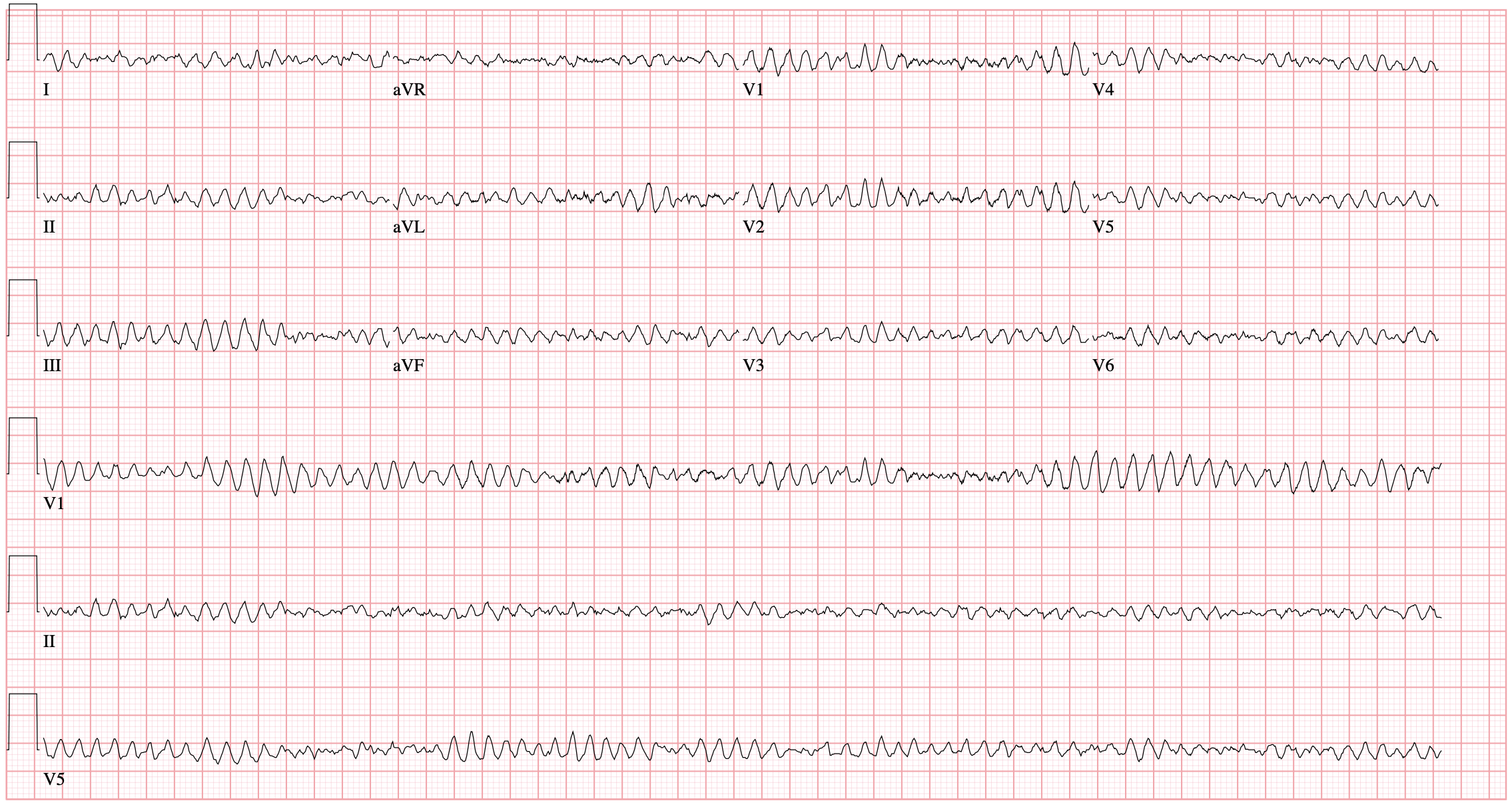

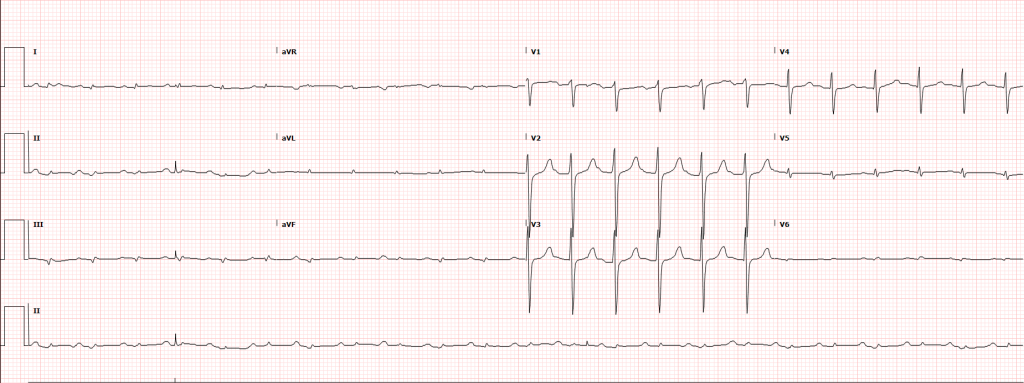

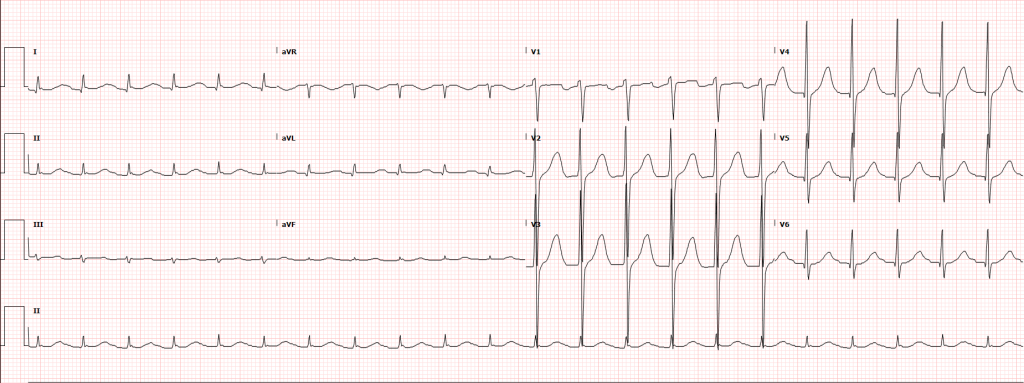

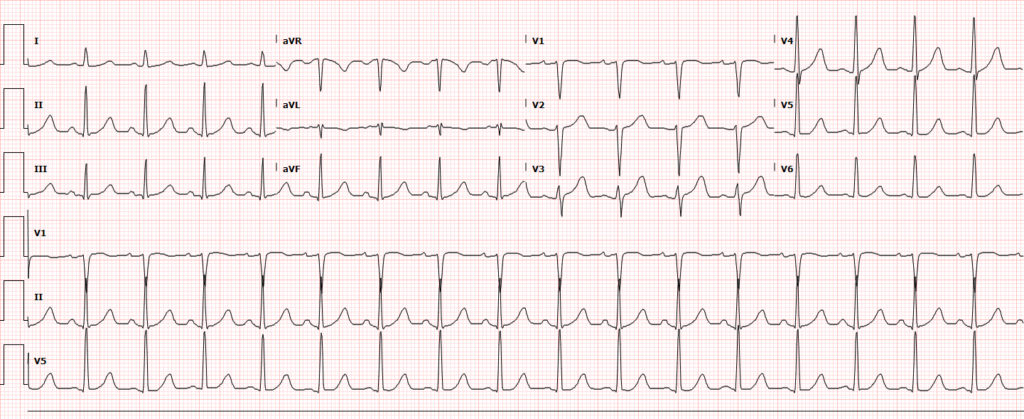

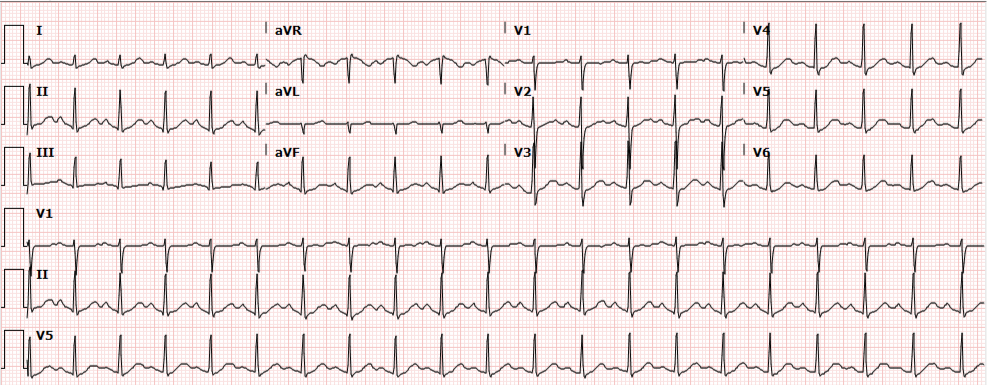

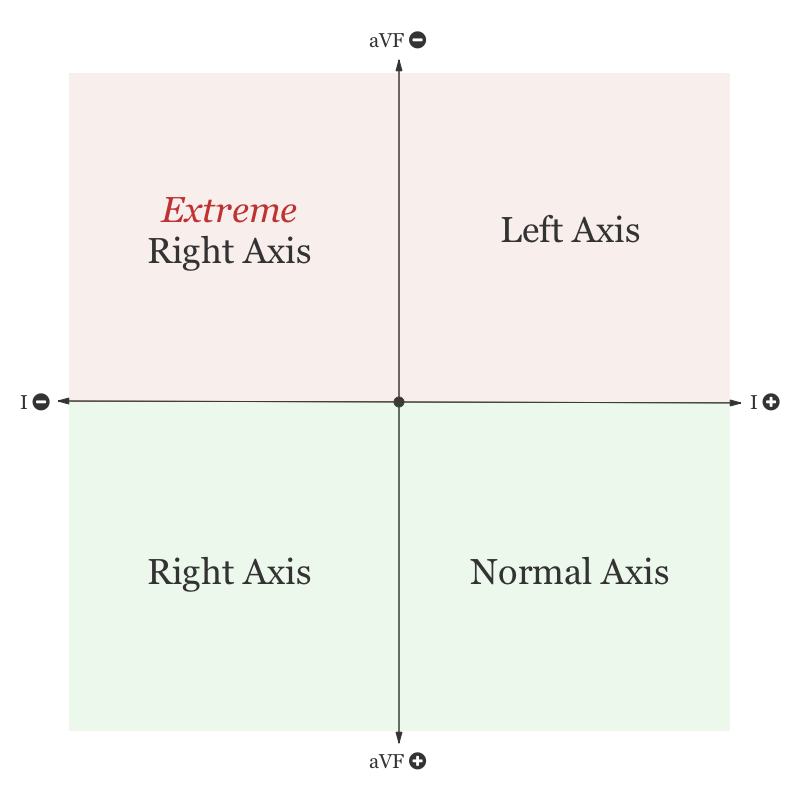

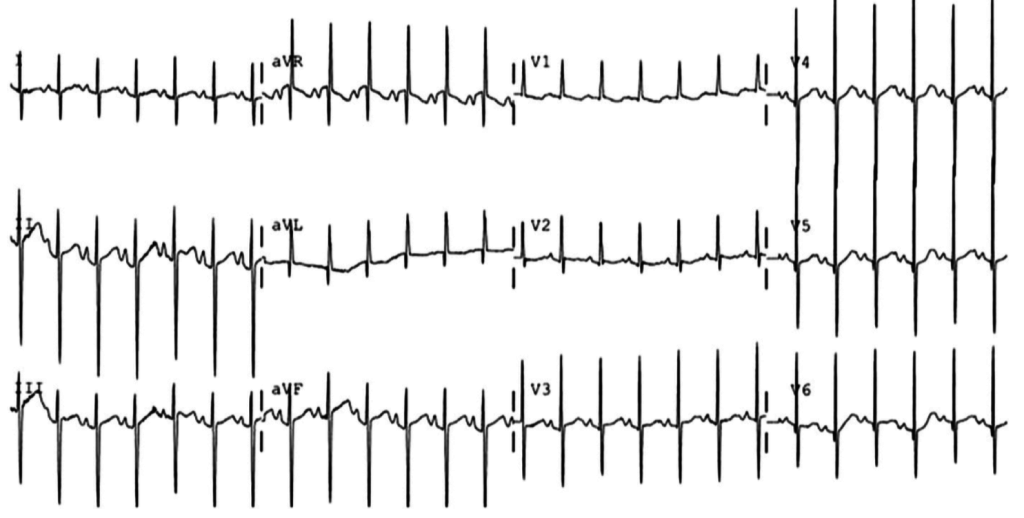

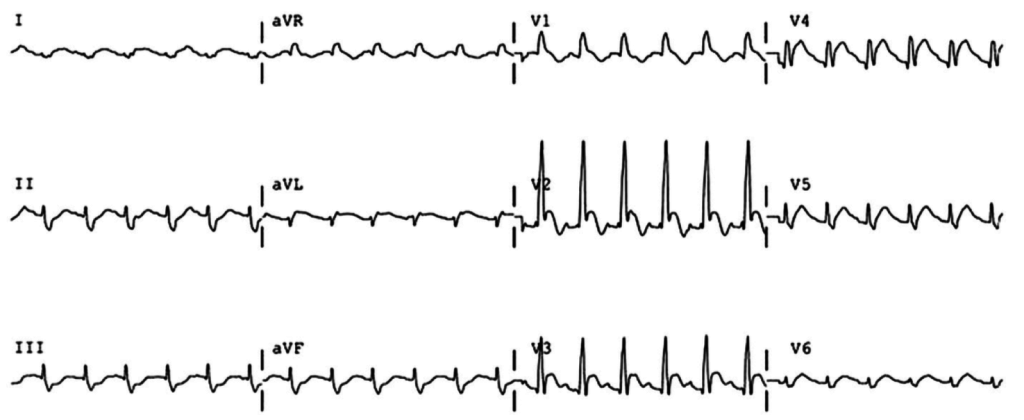

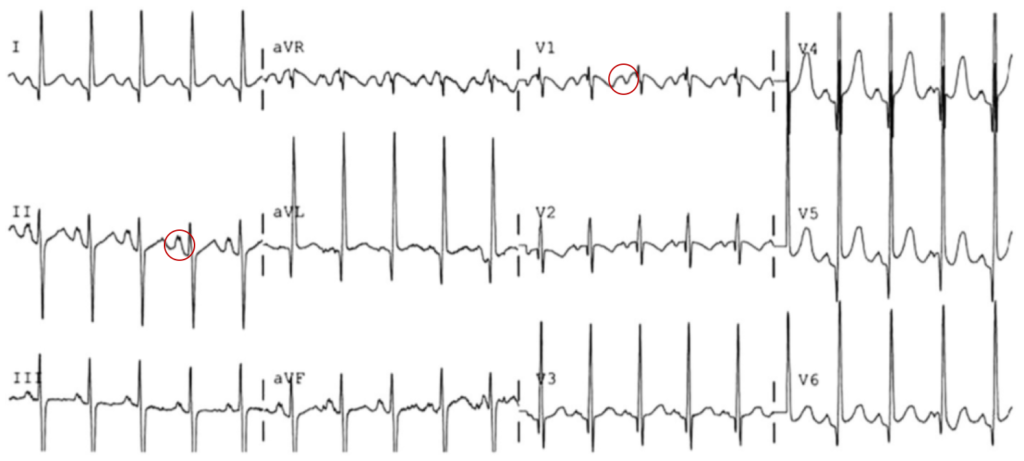

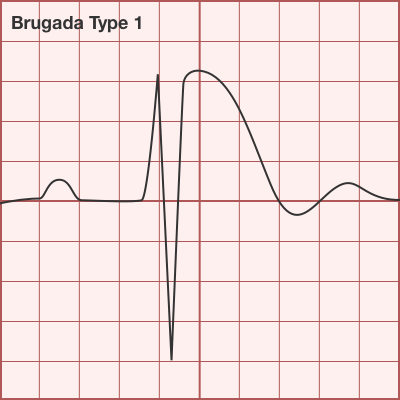

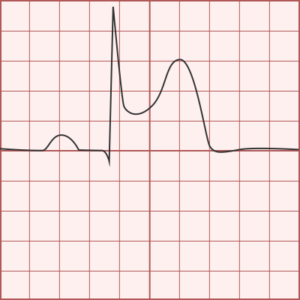

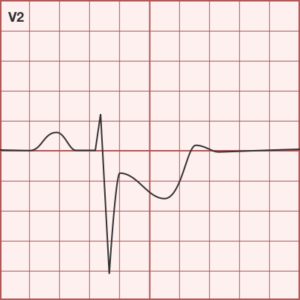

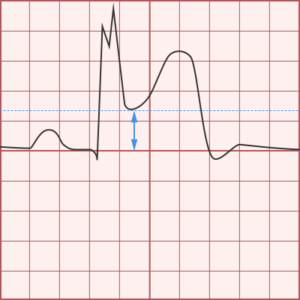

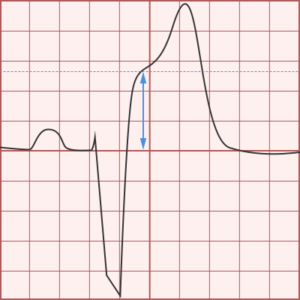

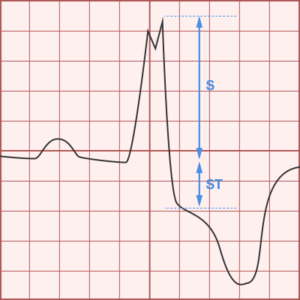

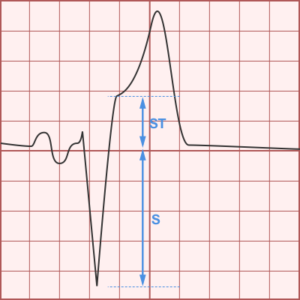

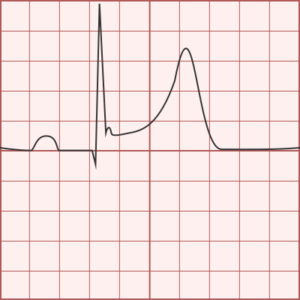

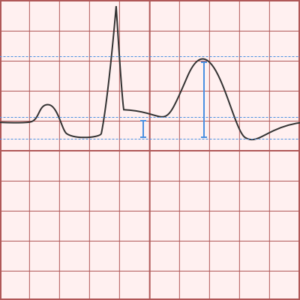

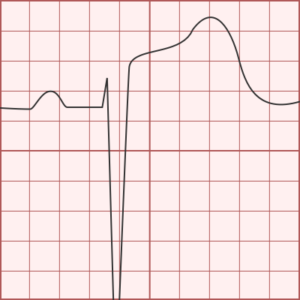

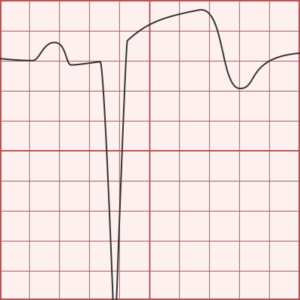

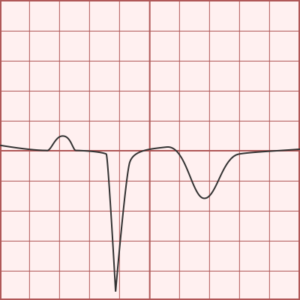

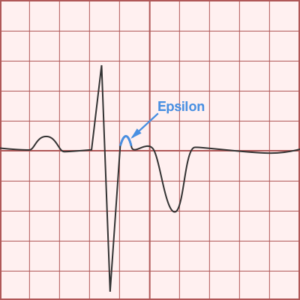

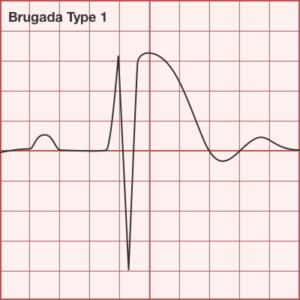

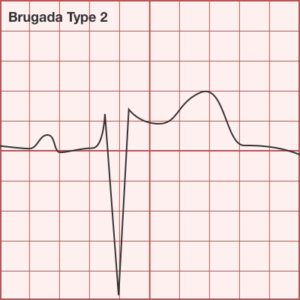

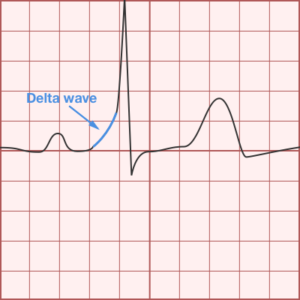

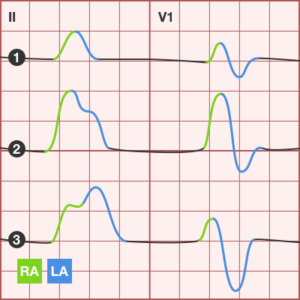

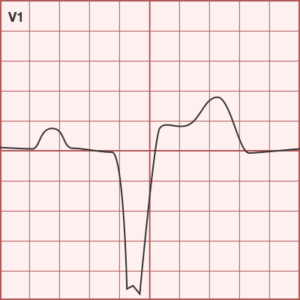

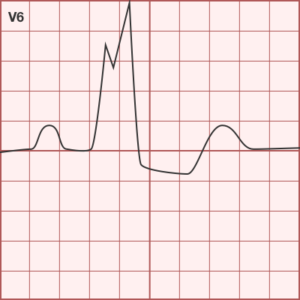

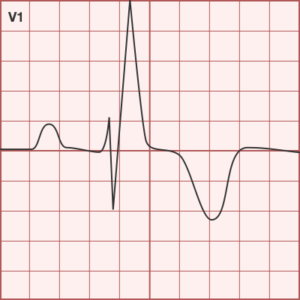

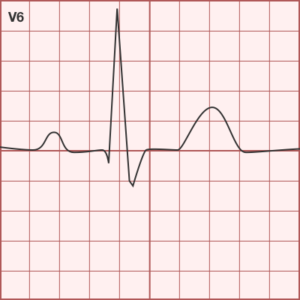

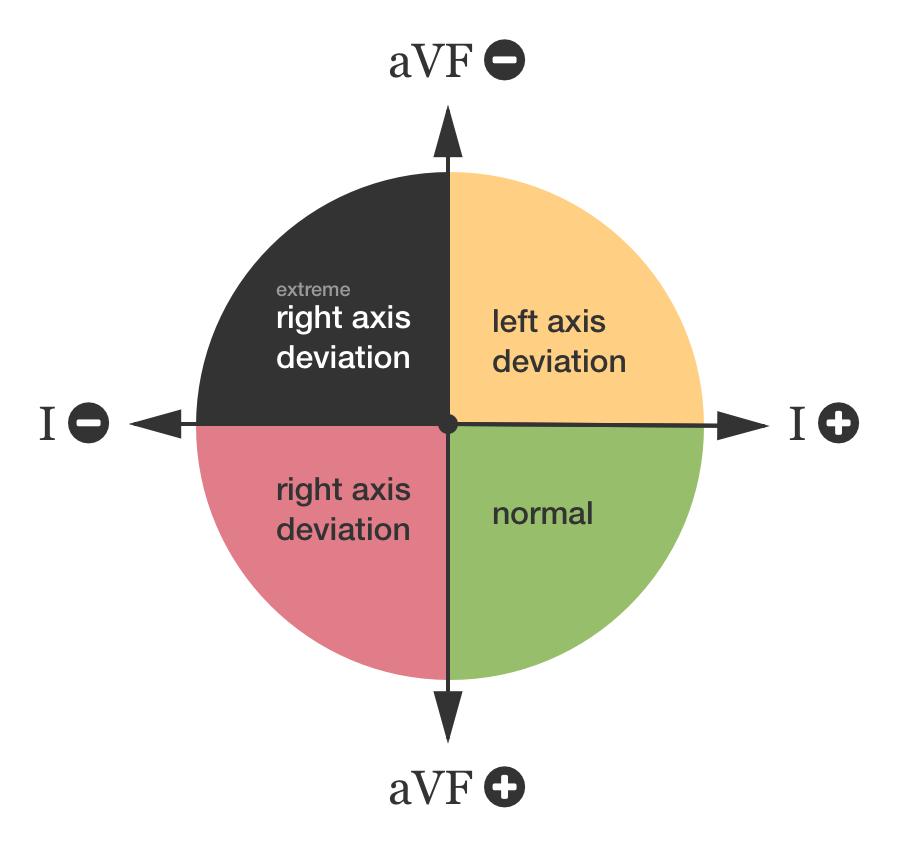

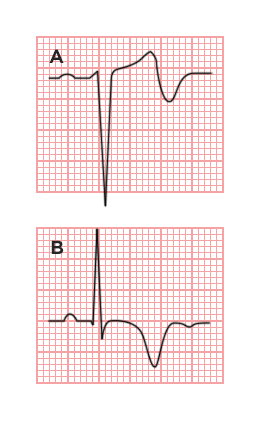

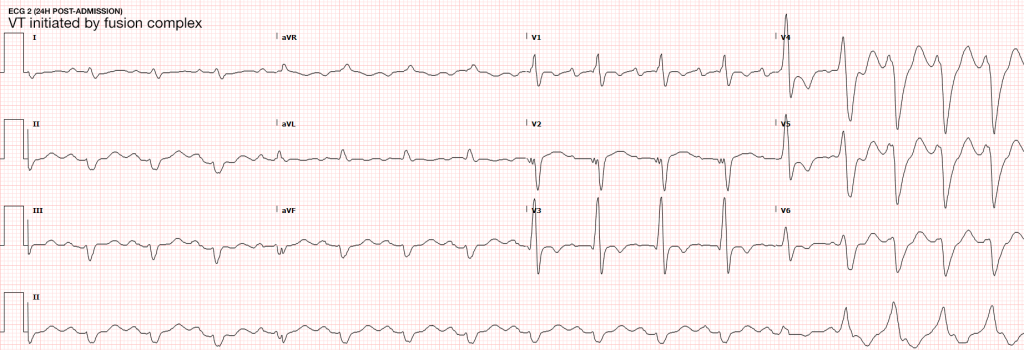

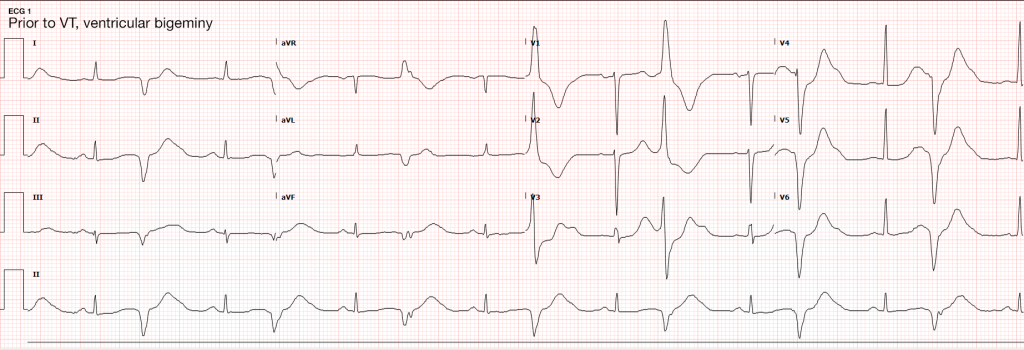

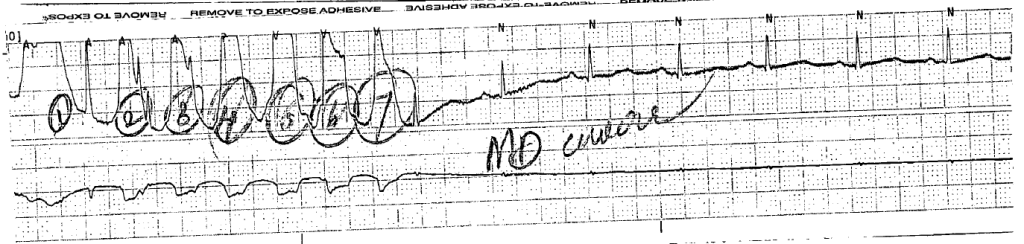

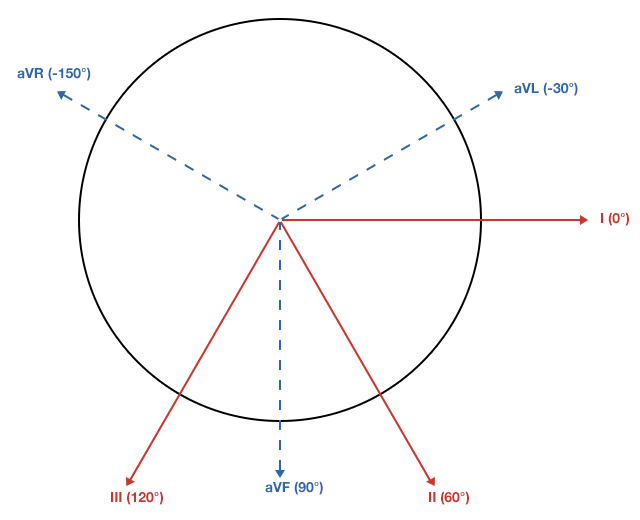

The initial rhythm detected upon evaluation is most suggestive of the etiologic precipitant. Pulseless ventricular tachycardia (pVT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF) is suggestive of a cardiac process – most commonly an acute coronary syndrome although heart failure or other structural and non-structural heart defects associated with dysrhythmias may be at fault4.

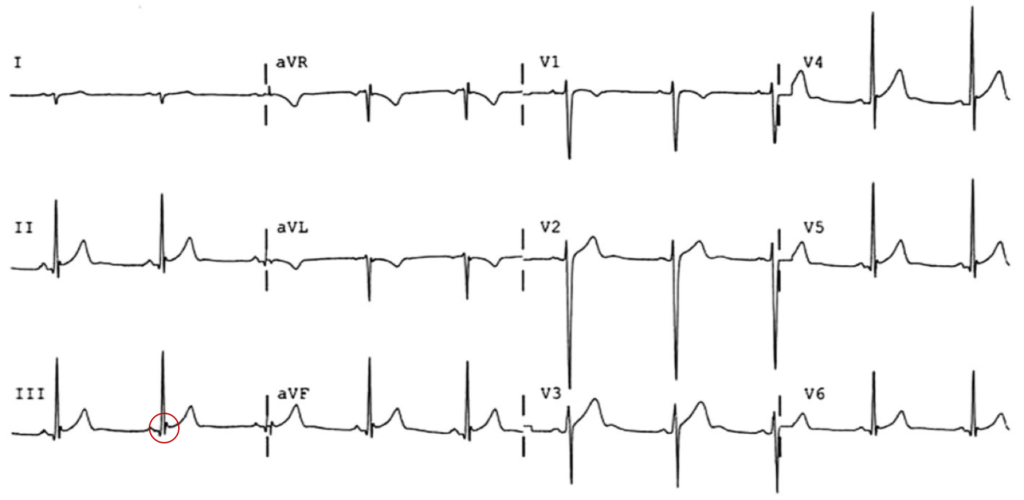

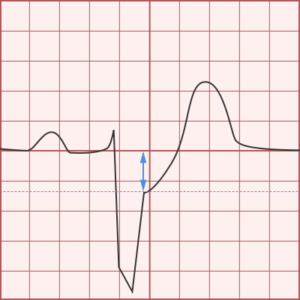

Pulseless electrical activity (PEA) presents a broader differential diagnosis as it essentially represents severe shock. The most common extra-cardiac cause is hypoxia – commonly secondary to pulmonary processes including small and large airway obstruction (bronchospasm, aspiration, foreign body, edema). Other causes include substance intoxication, medication adverse effect5,6, or electrolyte disturbances7. Finally, any precipitant of shock may ultimately lead to PEA, including hypovolemia/hemorrhage, obstruction (massive pulmonary embolus8, tamponade, tension pneumothorax), and distribution (sepsis).

Asystole is the absence of even disorganized electrical discharge and is the terminal degeneration of any of the previously-mentioned rhythms if left untreated.

Management of Cardiac Arrest

Optimizing survival outcomes in patients with cardiac arrest is dependent on early resuscitation with the prioritization of interventions demonstrated to have survival benefit. When advanced notice is available, prepare the resuscitation area including airway equipment (with adjuncts to assist ventilation and waveform capnography devices). Adopt the leadership position and assign roles for chest compressions, airway support, application of monitor/defibrillator, and establishment of peripheral access.

High-quality chest compressions with minimal interruptions are the foundation of successful resuscitation – and guideline changes prioritizing compressions have demonstrated detectable improvements in rates of successful resuscitation9,10. Measurement of quantitative end-tidal capnography can guide adequacy of chest compressions11,12 and an abrupt increase may signal restoration of circulation without necessitating interruptions of chest compressions13,14. Sustained, low measures of end-tidal CO2 despite appropriate resuscitation may signal futility and (alongside other factors) guides termination of resuscitation11,12.

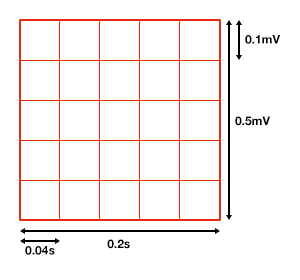

The next critical step in restoring circulation is prompt defibrillation of eligible rhythms (pVT/VF) when detected. The immediate delivery of 200J (uptitrated to the device maximum for subsequent shocks) of biphasic energy and restoration of a perfusing rhythm is one of few interventions with clear benefits. For pVT/VF that persists despite multiple countershocks (more than three), the addition of an intravenous antiarrhythmic appears to improve survival to hospital admission. The ARREST trial was a randomized controlled study comparing amiodarone to its diluent as placebo for OHCA with refractory pVT/VF showing significant improvement in survival to hospital admission for the amiodarone group15. This was followed by the ALIVE trial comparing amiodarone and lidocaine which showed significantly higher rates of survival to hospital admission in the amiodarone group16. However, a more recent randomized trial comparing amiodarone (in a novel diluent less likely to cause hypotension), lidocaine, and placebo in a similar patient population showed less convincing results, with no detected difference in survival or the secondary outcome of favorable neurological outcome for either amiodarone or lidocaine compared with placebo17. The heterogeneity of available data contributed to current guidelines which recommend that either amiodarone or lidocaine may be used for shock-refractory pVT/VF18.

Current guidelines also recommend the administration of vasopressors (epinephrine 1mg every 3-5 minutes). In one randomized controlled trial exploring the long-standing guideline recommendations, epinephrine was associated with increased rates of restoration of spontaneous circulation, though no significant impact on the primary outcome of survival to hospital discharge was identified19. Physiologically, increased systemic vascular resistance combined with positive beta-adrenergic impact on cardiac output would be expected to complement resuscitative efforts. However, more recent studies have suggested that arrest physiology and unanticipated pharmacologic effects may complicate this simplistic interpretation – particularly when patient-centered outcomes are emphasized. Research exploring the timing and amount of epinephrine suggest that earlier administration and higher cumulative doses are associated with negative impacts on survival to hospital discharge and favorable neurological outcomes20-22.

Ultimately, treatment should focus on optimal execution of measures with clear benefits (namely chest compressions and early defibrillation of eligible rhythms). Other management considerations with which the emergency physician is familiar with including establishing peripheral access and definitive airway management can be delayed.

Rapid Diagnostic Measures for the Identification of Reversible Processes

Traditional diagnostic measures are generally unavailable during an ongoing cardiac arrest resuscitation. The emergency medicine physician must rely on the physical examination and point-of-care tests with the objective of identifying potentially reversible processes. Measurement of capillary blood glucose can exclude hypoglycemia as a contributor. Point-of-care chemistry and blood gas analyzers can identify important electrolyte derangements, as well as clarifying the primary impulse in acid-base disturbances.

End-tidal capnography was discussed previously for the guidance of ongoing resuscitation, but it may have diagnostic utility in patients with SCD. In one study the initial EtCO2 was noted to be significantly higher for primary pulmonary processes (with PEA/asystole as presenting rhythm) compared to primary cardiac processes (with pVT/VF as presenting rhythm)23.

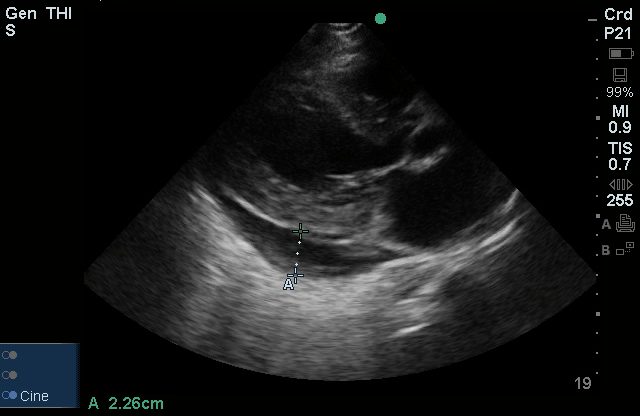

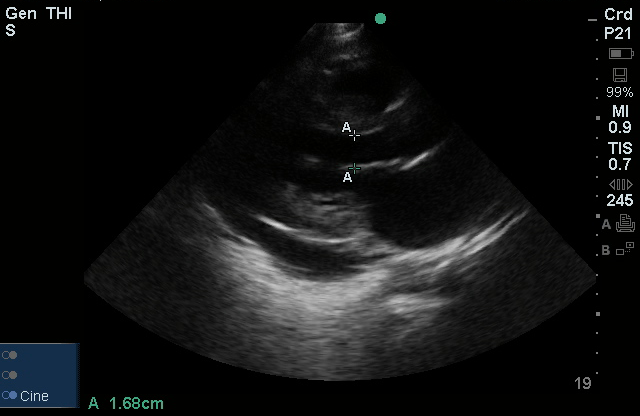

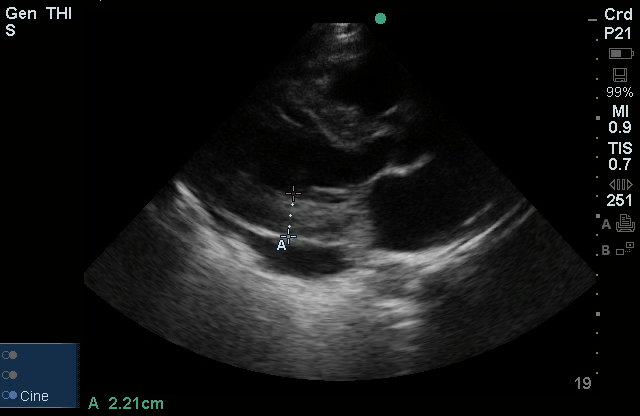

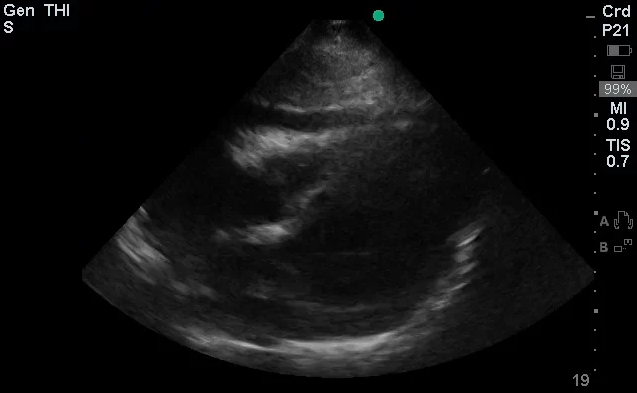

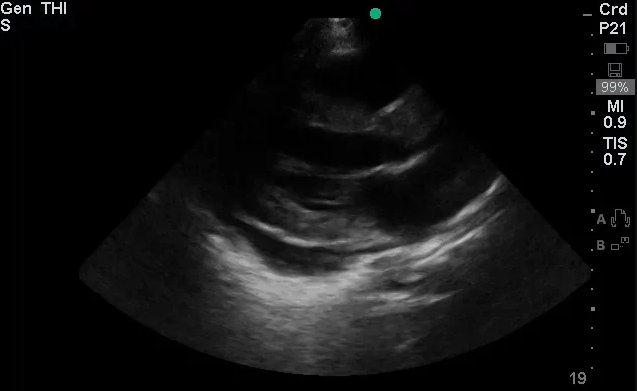

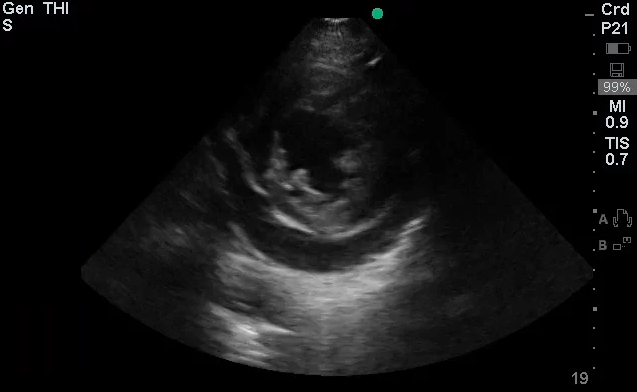

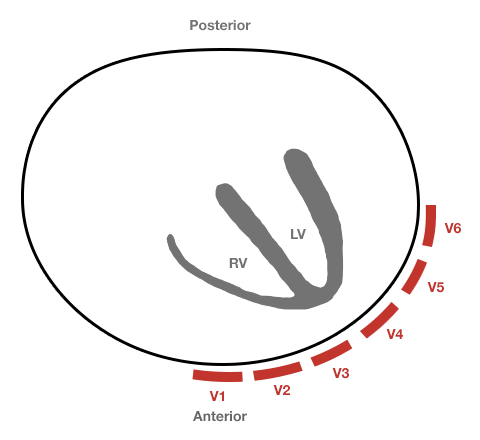

The use of point-of-care ultrasonography, particularly in PEA arrest where non-cardiac etiologies dominate, may help identify the etiology of arrest and direct therapy. Bedside ultrasonography should be directed first at assessment of cardiac function – examining the pericardial sac and gross abnormalities in chamber size. A pericardial effusion may suggest cardiac tamponade, ventricular collapse can be seen with hypovolemia, and asymmetric right-ventricular dilation points to pulmonary embolus where thrombolysis should be considered8. If cardiac ultrasound is unrevealing, thoracic ultrasound can identify pneumothorax24-27.

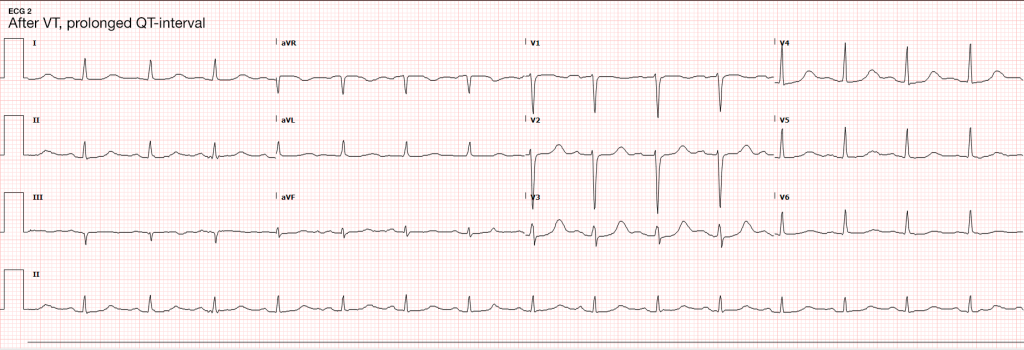

In the absence of ultrasonographic abnormalities, attention turns to other rapidly reversible precipitants first. If opioid toxicity is a consideration, an attempt at reversal with naloxone has few adverse effects. If any detected rhythm is a polymorphic ventricular tachycardia characteristic of torsades de pointes – rapid infusion of magnesium sulfate should follow defibrillation. Other potentially reversible medications or toxins should be managed as appropriate.

Post-Resuscitation Steps

After successful restoration of circulation, the next management steps are critical to the patient’s long-term outcomes. A definitive airway should be established if not already secured (and if restoration of circulation was not associated with neurological recovery sufficient for independent airway protection). Circulatory support should continue with fluid resuscitation and vasopressors to maintain end-organ perfusion.

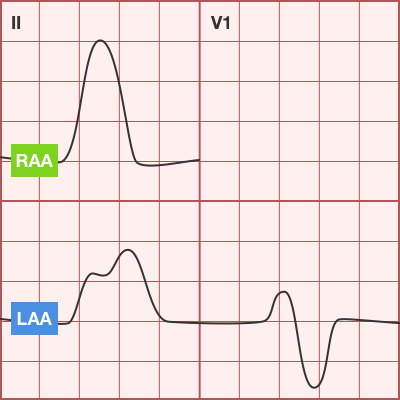

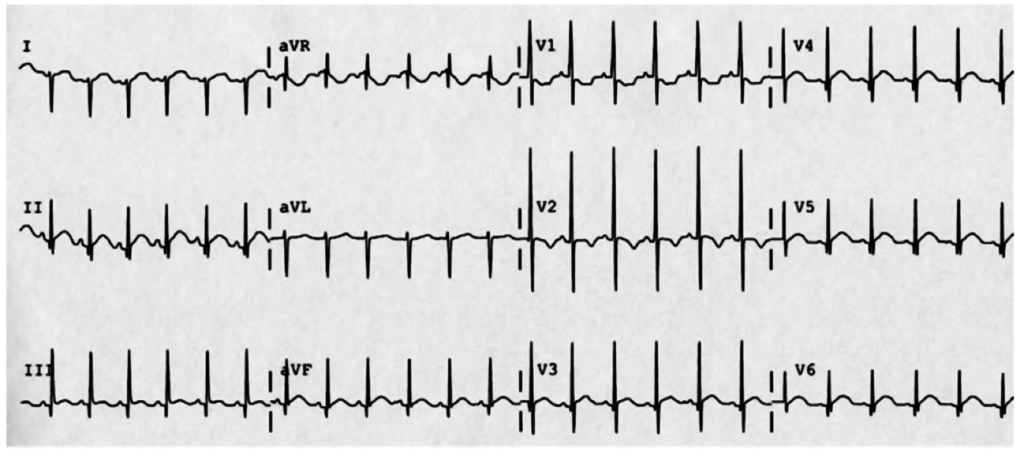

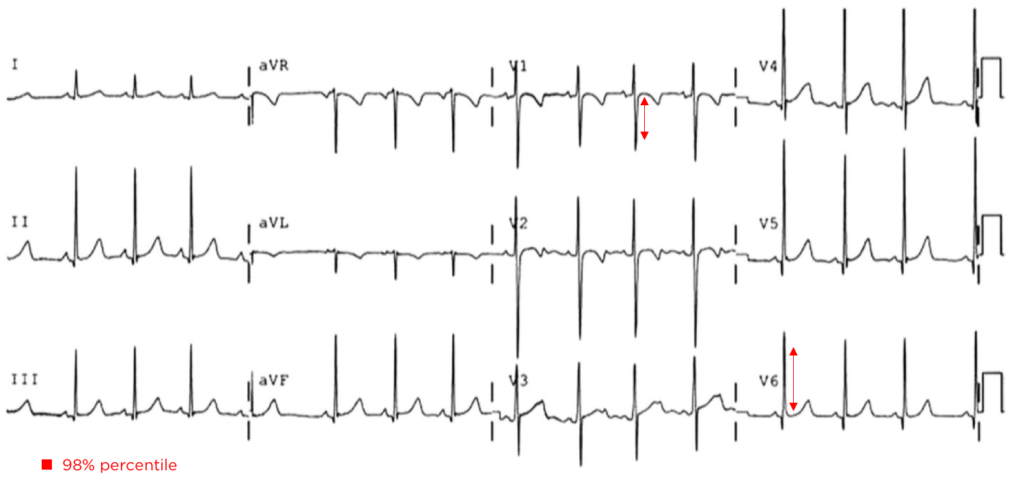

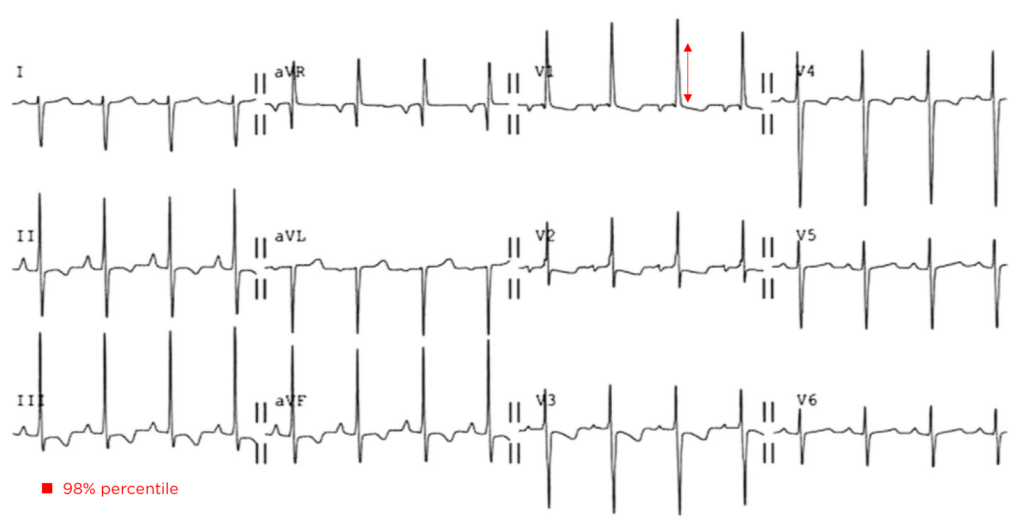

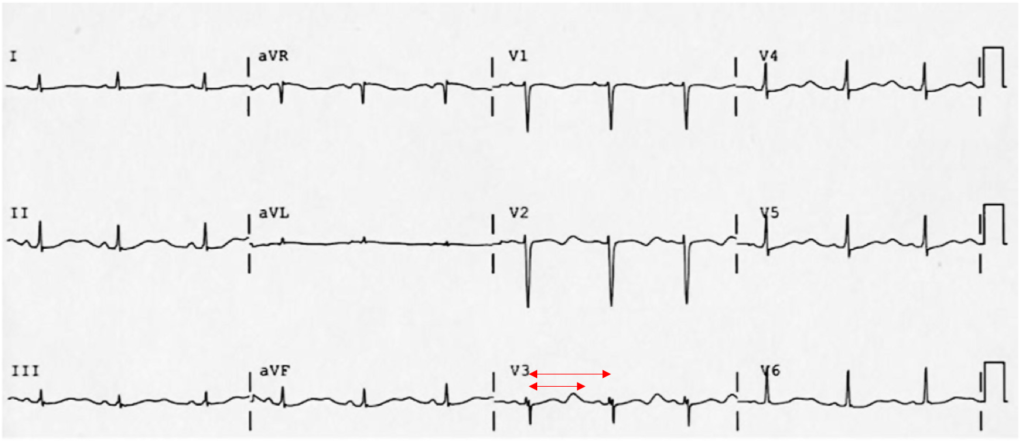

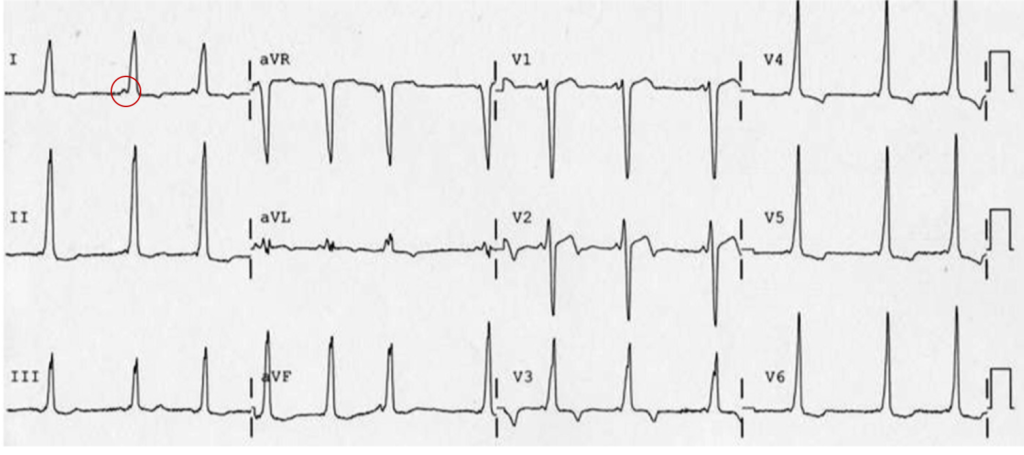

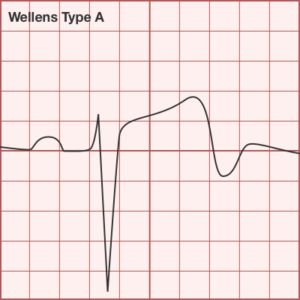

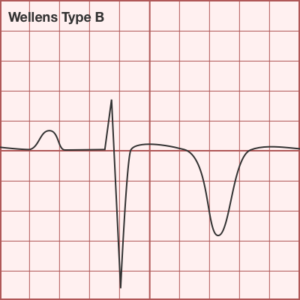

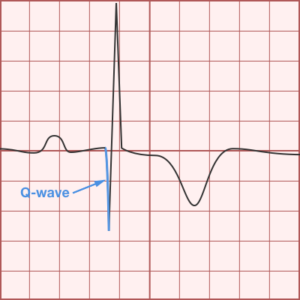

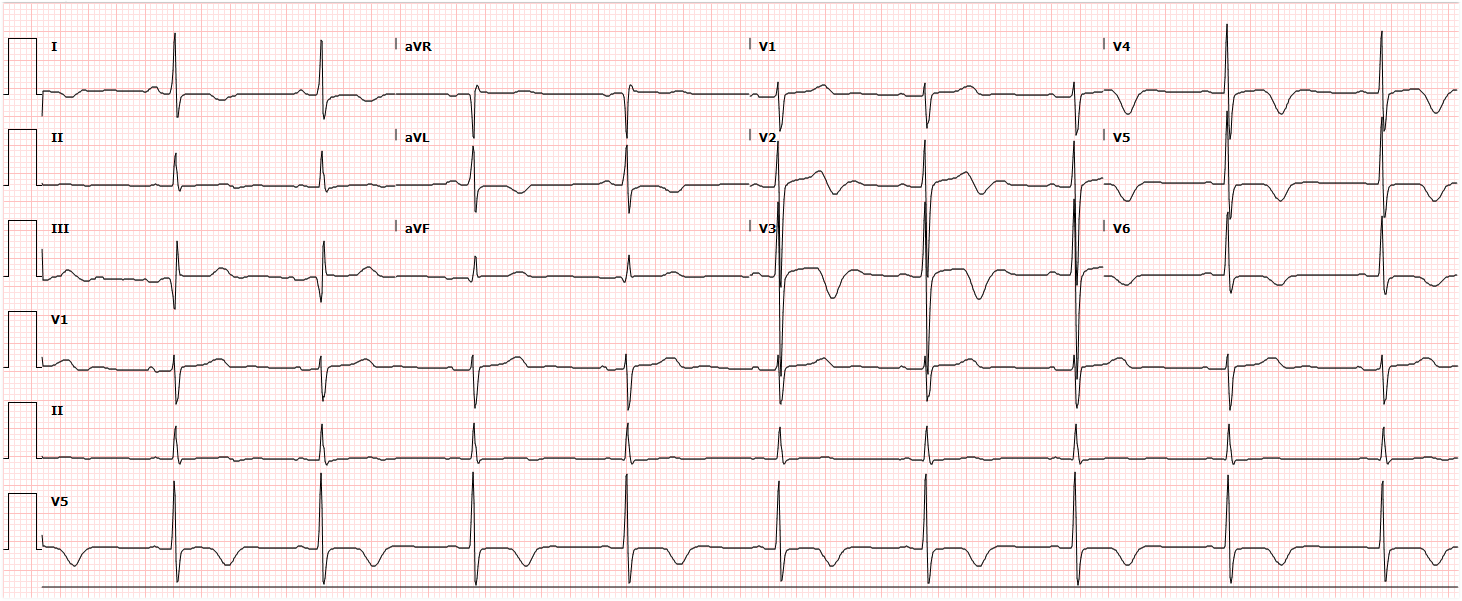

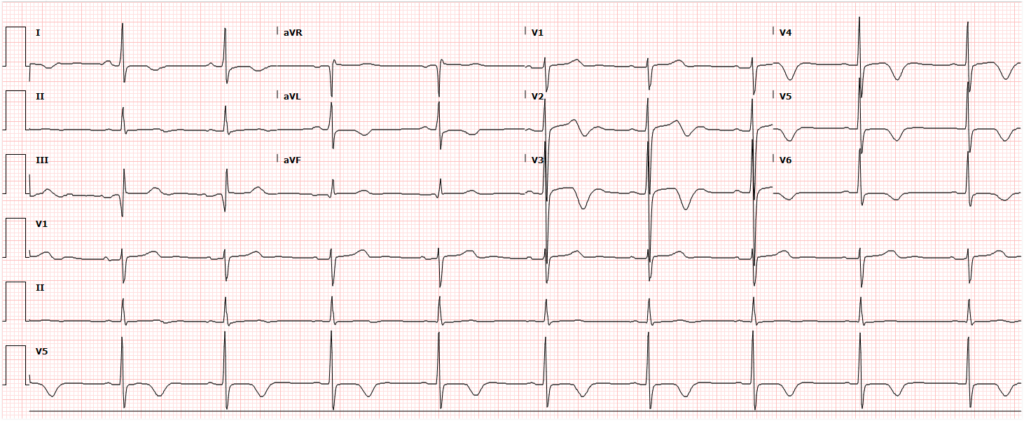

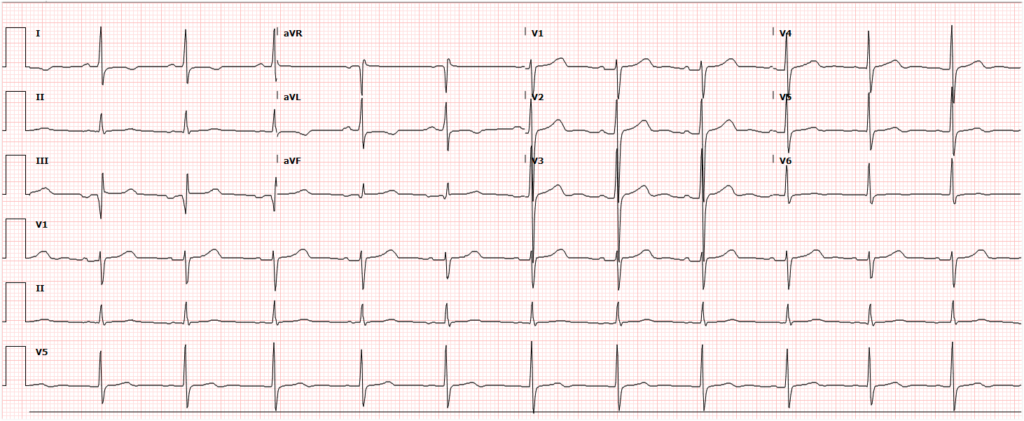

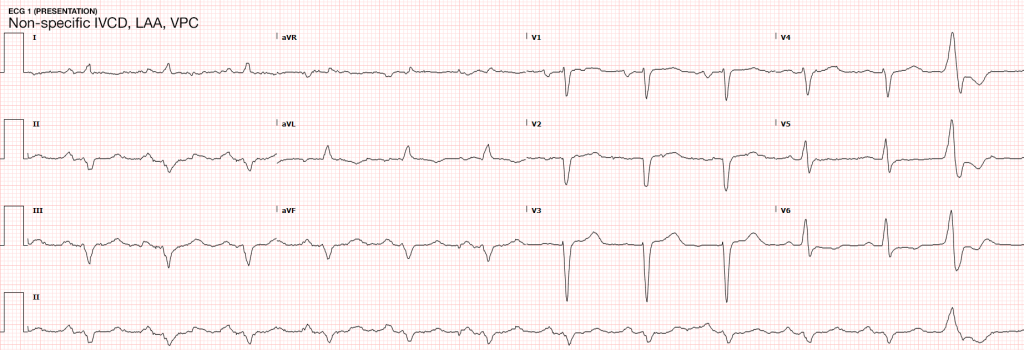

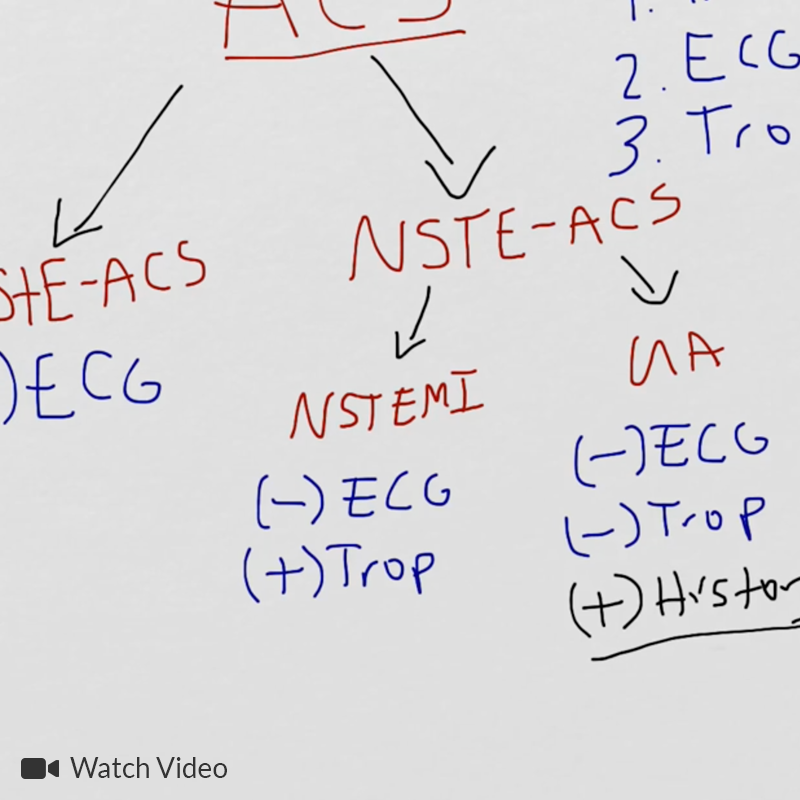

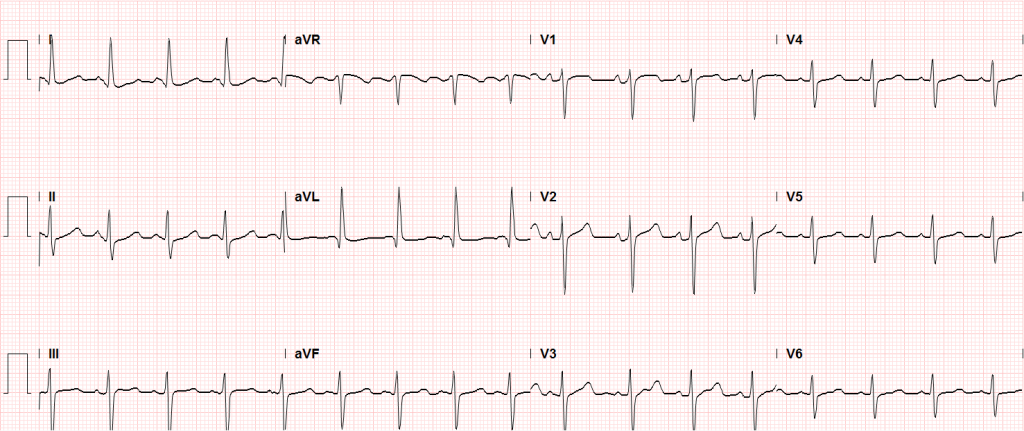

An immediate ECG should be performed to identify infarction, ischemia or precipitants of dysrhythmia. ST-segment elevation after return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) warrants emergent angiography and possible intervention. However, given the prevalence of cardiac causes (of which coronary disease is most common) for patients with pVT/VF arrest, the presence of ST elevations is likely of insufficient sensitivity to identify all patients who would benefit from angiography. Several studies and meta-analyses have explored a more inclusive selection strategy for angiography (patients without obvious non-cardiac causes for arrest), all of which identified survival benefits with angiography and successful angioplasty when possible28-30.

Finally, the induction of hypothermia (or targeted temperature management) has significant benefits in survivors of cardiac arrest and can be instituted in the emergency department. Studies first targeted a core temperature of 32-24°C, with a randomized controlled trial demonstrating higher rates of favorable neurological outcome and reduced mortality31. More recent studies suggest that a more liberal temperature target does not diffuse the positive effects of induced hypothermia. A randomized trial of 939 patients with OHCA comparing a targeted temperature of 33°C vs 36°C suggested that a lower temperature target did not confer higher benefit to mortality or recovery of neurological function32. The more liberal temperature target may alleviate adverse effects associated with hypothermia which include cardiovascular effects (bradycardia), electrolyte derangements (during induction and rewarming), and possible increased risk of infections33. Targeted temperature management is achieved with external cooling measures or infusion of cooled fluids, rarely requiring more invasive measures34. Aggregate review of available data in a recent meta-analysis further supports the use of targeted temperature management after cardiac arrest as standard-of-care35.

References

- Bergum D, Nordseth T, Mjølstad OC, Skogvoll E, Haugen BO. Causes of in-hospital cardiac arrest – Incidences and rate of recognition. Resuscitation. 2015;87:63-68. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.11.007.

- Wallmuller C, Meron G, Kurkciyan I, Schober A, Stratil P, Sterz F. Causes of in-hospital cardiac arrest and influence on outcome. Resuscitation. 2012;83(10):1206-1211. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.05.001.

- Vaartjes I, Hendrix A, Hertogh EM, et al. Sudden death in persons younger than 40 years of age: incidence and causes. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation. 2009;16(5):592-596. doi:10.1097/HJR.0b013e32832d555b.

- Zheng ZJ, Croft JB, Giles WH, Mensah GA. Sudden cardiac death in the United States, 1989 to 1998. Circulation. 2001;104(18):2158-2163.

- Hoes AW, Grobbee DE, Lubsen J, Man in ‘t Veld AJ, van der Does E, Hofman A. Diuretics, beta-blockers, and the risk for sudden cardiac death in hypertensive patients. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123(7):481-487.

- Siscovick DS, Raghunathan TE, Psaty BM, et al. Diuretic therapy for hypertension and the risk of primary cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(26):1852-1857. doi:10.1056/NEJM199406303302603.

- Gettes LS. Electrolyte abnormalities underlying lethal and ventricular arrhythmias. Circulation. 1992;85(1 Suppl):I70-I76.

- Kürkciyan I, Meron G, Sterz F, et al. Pulmonary embolism as a cause of cardiac arrest: presentation and outcome. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(10):1529-1535.

- Callaway CW, Soar J, Aibiki M, et al. Part 4: Advanced Life Support: 2015 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations. In: Vol 132. American Heart Association, Inc.; 2015:S84-S145. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000273.

- Kudenchuk PJ, Redshaw JD, Stubbs BA, et al. Impact of changes in resuscitation practice on survival and neurological outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest resulting from nonshockable arrhythmias. Circulation. 2012;125(14):1787-1794. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.064873.

- Touma O, Davies M. The prognostic value of end tidal carbon dioxide during cardiac arrest: a systematic review. Resuscitation. 2013;84(11):1470-1479. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.07.011.

- Levine RL, Wayne MA, Miller CC. End-tidal carbon dioxide and outcome of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(5):301-306. doi:10.1056/NEJM199707313370503.

- Garnett AR, Ornato JP, Gonzalez ER, Johnson EB. End-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. JAMA. 1987;257(4):512-515.

- Falk JL, Rackow EC, Weil MH. End-tidal carbon dioxide concentration during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(10):607-611. doi:10.1056/NEJM198803103181005.

- Kudenchuk PJ, Cobb LA, Copass MK, et al. Amiodarone for resuscitation after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(12):871-878. doi:10.1056/NEJM199909163411203.

- Dorian P, Cass D, Schwartz B, Cooper R, Gelaznikas R, Barr A. Amiodarone as compared with lidocaine for shock-resistant ventricular fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(12):884-890. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa013029.

- Kudenchuk PJ, Brown SP, Daya M, et al. Amiodarone, Lidocaine, or Placebo in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(18):1711-1722. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1514204.

- Neumar RW, Shuster M, Callaway CW, et al. Part 1: Executive Summary: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. In: Vol 132. American Heart Association, Inc.; 2015:S315-S367. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000252.

- Jacobs IG, Finn JC, Jelinek GA, Oxer HF, Thompson PL. Effect of adrenaline on survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Resuscitation. 2011;82(9):1138-1143. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.06.029.

- Hagihara A, Hasegawa M, Abe T, Nagata T, Wakata Y, Miyazaki S. Prehospital epinephrine use and survival among patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2012;307(11):1161-1168. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.294.

- Dumas F, Bougouin W, Geri G, et al. Is epinephrine during cardiac arrest associated with worse outcomes in resuscitated patients? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(22):2360-2367. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.036.

- Andersen LW, Kurth T, Chase M, et al. Early administration of epinephrine (adrenaline) in patients with cardiac arrest with initial shockable rhythm in hospital: propensity score matched analysis. BMJ. 2016;353:i1577. doi:10.1136/bmj.i1577.

- Grmec S, Lah K, Tusek-Bunc K. Difference in end-tidal CO2 between asphyxia cardiac arrest and ventricular fibrillation/pulseless ventricular tachycardia cardiac arrest in the prehospital setting. Crit Care. 2003;7(6):R139-R144. doi:10.1186/cc2369.

- Rose JS, Bair AE, Mandavia D, Kinser DJ. The UHP ultrasound protocol: a novel ultrasound approach to the empiric evaluation of the undifferentiated hypotensive patient. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2001;19(4):299-302. doi:10.1053/ajem.2001.24481.

- Hernandez C, Shuler K, Hannan H, Sonyika C, Likourezos A, Marshall J. C.A.U.S.E.: Cardiac arrest ultra-sound exam—A better approach to managing patients in primary non-arrhythmogenic cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2008;76(2):198-206. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.06.033.

- Chardoli M, Heidari F, Shuang-ming S, et al. Echocardiography integrated ACLS protocol versus con- ventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation in patients with pulseless electrical activity cardiac arrest. Chinese Journal of Traumatology. 2012;15(5):284-287. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1008-1275.2012.05.005.

- Zengin S, Yavuz E, Al B, et al. Benefits of cardiac sonography performed by a non-expert sonographer in patients with non-traumatic cardiopulmonary arrest. Resuscitation. 2016;102:105-109. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.02.025.

- Spaulding CM, Joly LM, Rosenberg A, et al. Immediate coronary angiography in survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(23):1629-1633. doi:10.1056/NEJM199706053362302.

- Dumas F, Cariou A, Manzo-Silberman S, et al. Immediate Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Is Associated With Better Survival After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: Insights From the PROCAT (Parisian Region Out of Hospital Cardiac Arrest) Registry. Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2010;3(3):200-207. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.109.913665.

- Millin MG, Comer AC, Nable JV, et al. Patients without ST elevation after return of spontaneous circulation may benefit from emergent percutaneous intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2016;108:54-60. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.09.004.

- Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study Group. Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):549-556. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa012689.

- Nielsen N, Wetterslev J, Cronberg T, et al. Targeted Temperature Management at 33°C versus 36°C after Cardiac Arrest. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(23):2197-2206. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1310519.

- Polderman KH, Peerdeman SM, Girbes AR. Hypophosphatemia and hypomagnesemia induced by cooling in patients with severe head injury. J Neurosurg. 2001;94(5):697-705. doi:10.3171/jns.2001.94.5.0697.

- Polderman KH, Herold I. Therapeutic hypothermia and controlled normothermia in the intensive care unit: Practical considerations, side effects, and cooling methods*. Critical Care Medicine. 2009;37(3):1101-1120. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181962ad5.

- Schenone AL, Cohen A, Patarroyo G, et al. Therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest: A systematic review/meta-analysis exploring the impact of expanded criteria and targeted temperature. Resuscitation. 2016;108:102-110. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.07.238.