HPI:

48F with a history of SLE presenting with two weeks of fevers and joint pain. The patient reports progressive development of these symptoms associated with malaise and muscle aches. She also reports two days of cough productive of yellow sputum, but denies chest pain, shortness of breath or hemoptysis. She states that these symptoms are comparable to prior lupus flares but have persisted longer than usual. She has not travelled or been hospitalized recently and has no sick contacts.

PMH:

- SLE

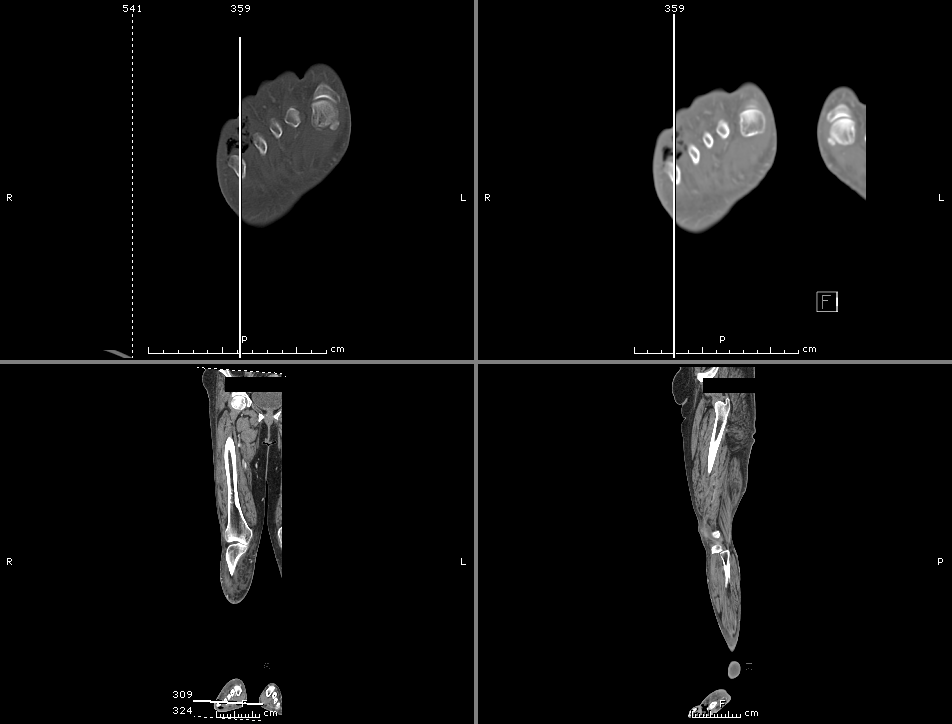

- AVN left hip

PSH:

- Total hip arthroplasty

FH:

Non-contributory

SHx:

- Denies tobacco, alcohol or drug use.

- Works as an accountant.

- No history of TB exposure.

Meds:

- Methotrexate 50mg p.o. weekly

- Plaquenil 400mg p.o. daily

- MVI

Allergies:

NKDA

Physical Exam:

| VS: | T | 39.4 | HR | 138 | RR | 19 | BP | 97/61 | O2 | 98% 2L NC |

| Gen: | Alert, responsive and in no acute distress. | |||||||||

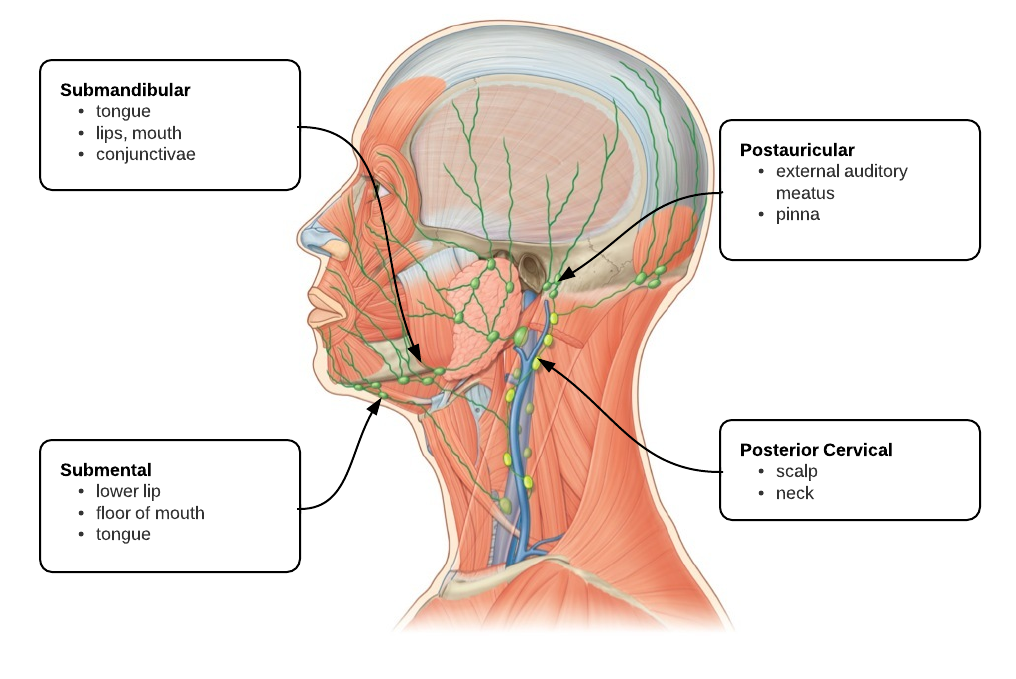

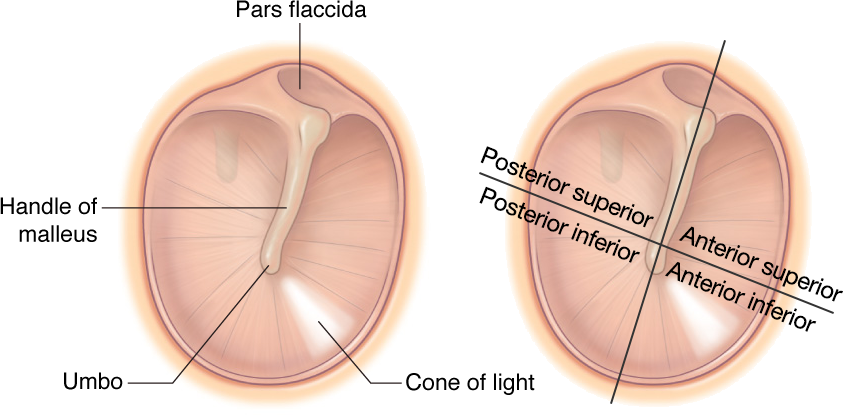

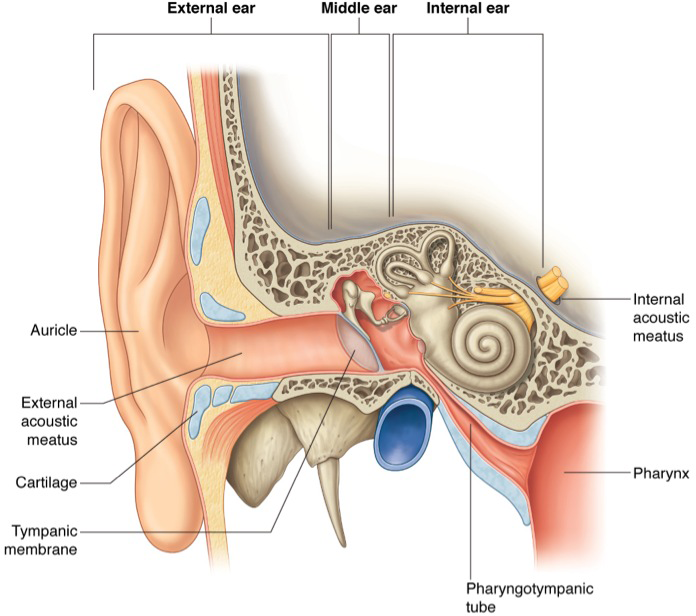

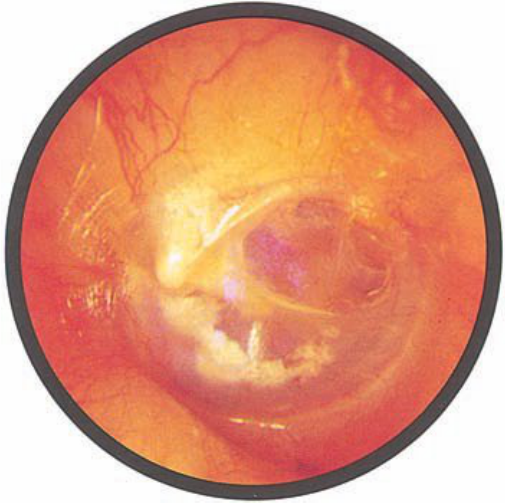

| HEENT: | PERRL, dry mucous membranes, no oropharyngeal lesions or erythema, TM intact bilaterally, no cervical lymphadenopathy, neck supple. | |||||||||

| CV: | Tachycardia, regular rhythm without additional heart sounds. | |||||||||

| Lungs: | Clear to auscultation bilaterally. | |||||||||

| Abd: | +BS, soft, non-tender, non-distended, no rebound/guarding. | |||||||||

| Ext: | No peripheral edema, extremities warm and well-perfused, diffuse tenderness to palpation and resisted range of motion of joints with particular involvement of bilateral shoulders, elbows, knees and ankles. No effusion noted, no erythema or warmth. | |||||||||

| Neuro: | Alert, oriented to self, location and time. PERRL, EOMI, facial sensation intact, facial muscles symmetric, palate rises symmetrically, tongue protrudes midline without fasciculation, peripheral sensation and motor strength grossly intact with normal gait. | |||||||||

Labs/Studies:

- 0h:

- CBC: 6.0/7.7/23.5/259

- BMP: 138/2.8/116/18/12/0.66/71

- Ca: 5.0 (corrected for hypoalbuminemia: 6.9)

- Mg: 1.1

- Lactate: 0.7

- ESR: 81 (0-20)

- CRP: 7.99 (0-0.74)

- C3: 60 (79-152)

- C4: 13 (16-38)

- 12h:

- BMP: 142/4.6/113/26/15/0.75/128

- Ca: 7.8

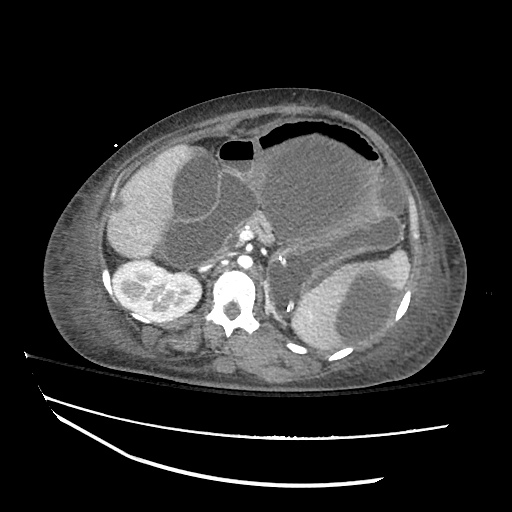

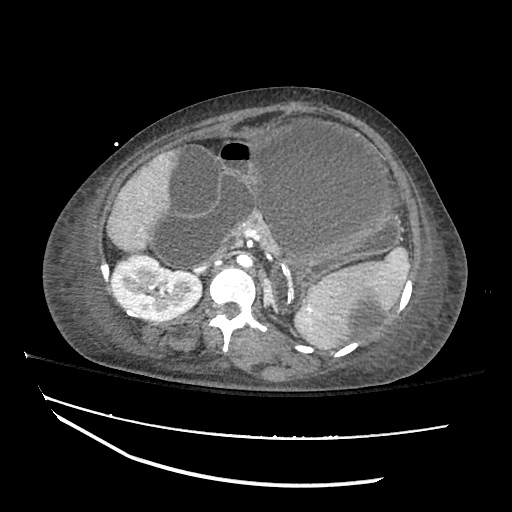

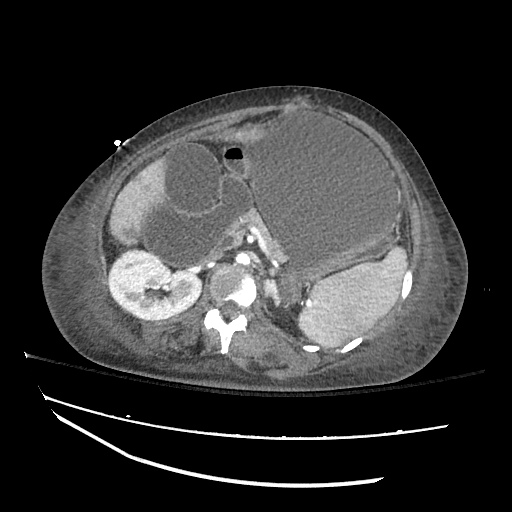

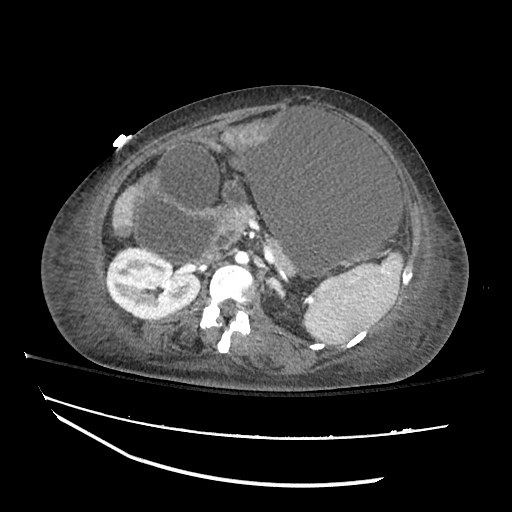

Imaging:

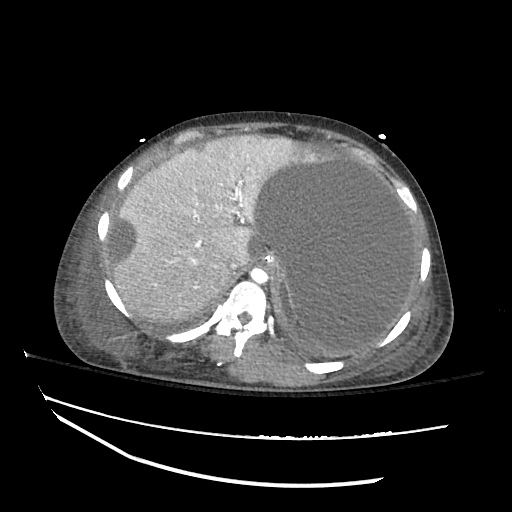

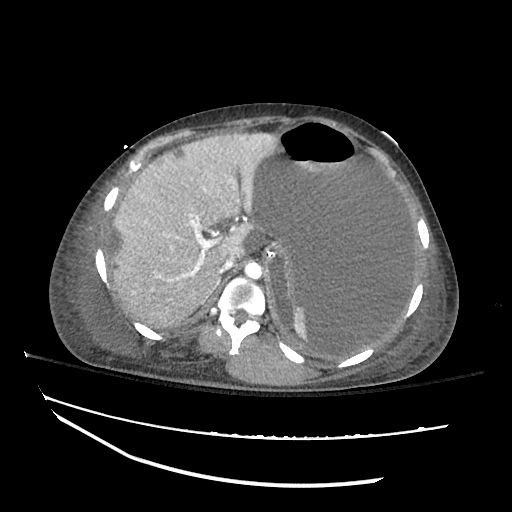

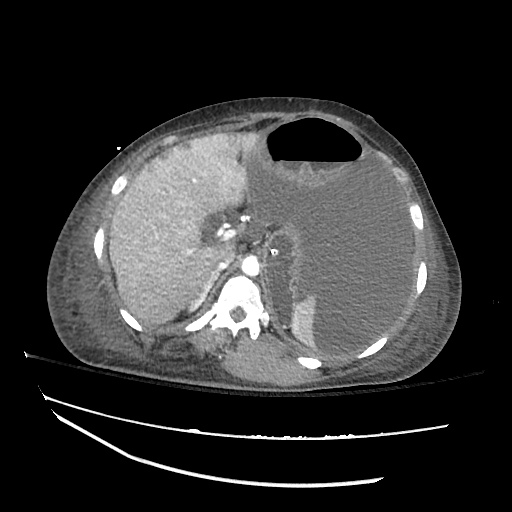

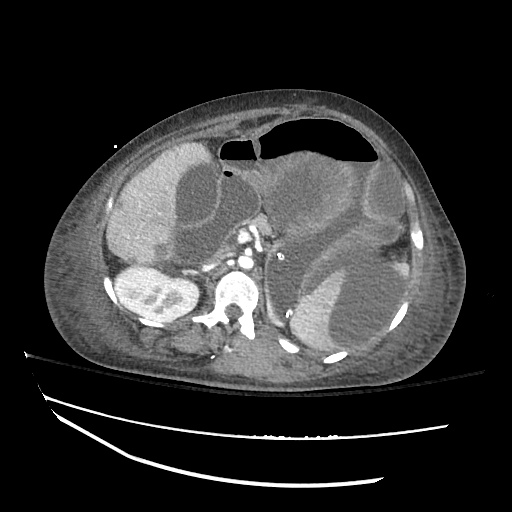

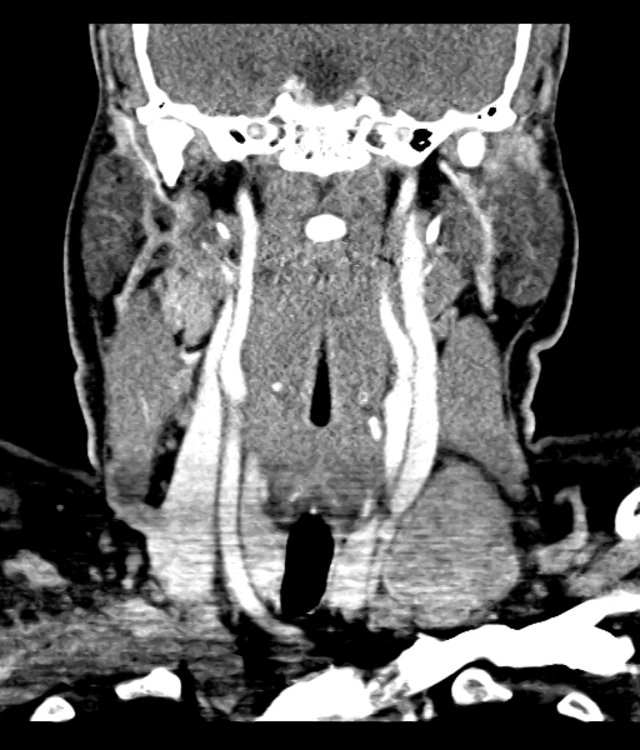

- CXR: Negative for acute cardiopulmonary process.

Assessment/Plan:

48F with a history of SLE presenting with fever and polyarticular arthralgia.

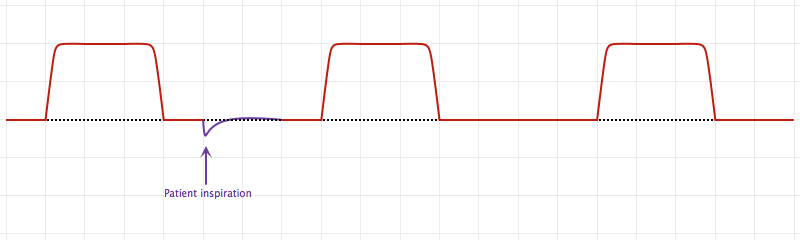

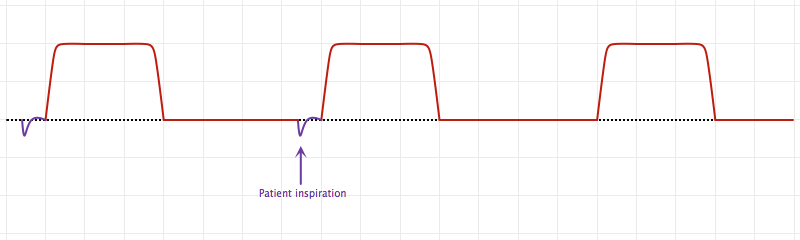

#SIRS: Fever and tachycardia in the setting of immunosuppression. The differential diagnosis includes pneumonia (bacterial, viral, less-likely fungal), which would be community-acquired. Association with polyarticular arthralgia suggests symptoms may represent lupus flare given no leukocytosis and elevated CRP.

#Hypocalcemia: Asymptomatic, likely due to hypoalbuminemia and hypomagnesemia. Improved after IV fluids and correction of hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia.

Hospital Course:

The patient was admitted and completed a 7-day course of ceftriaxone and azithromycin. Rheumatology was consulted for management of lupus flare, which included resuming home medications and a prednisone taper upon discharge.

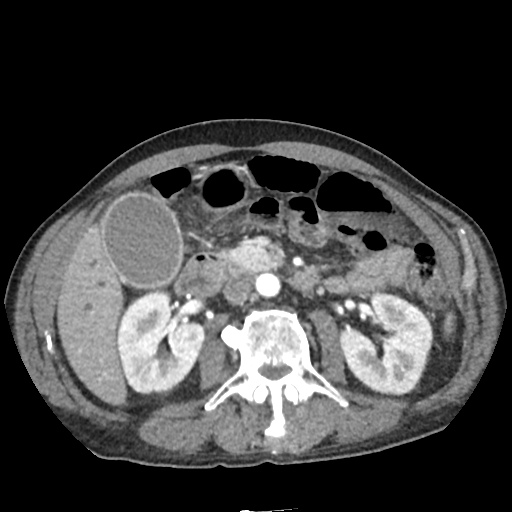

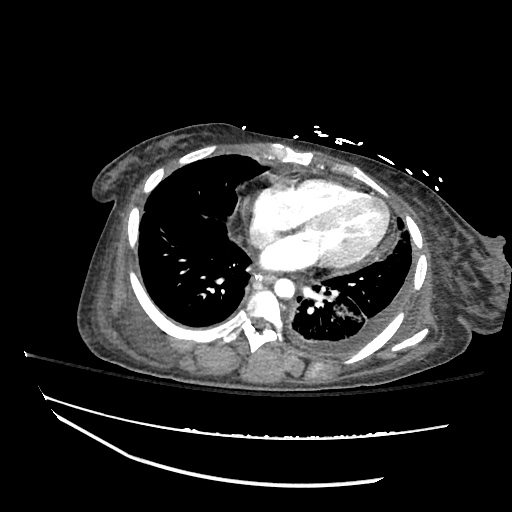

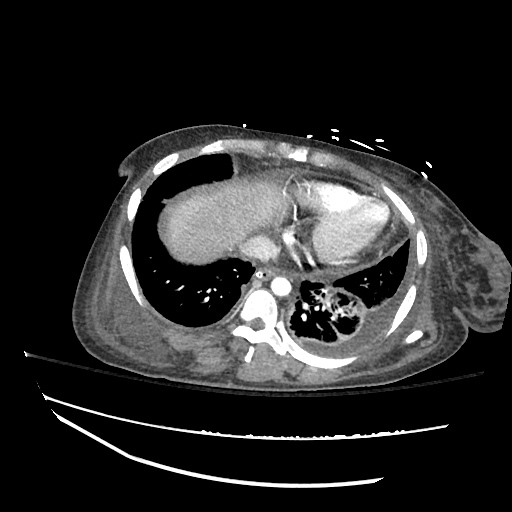

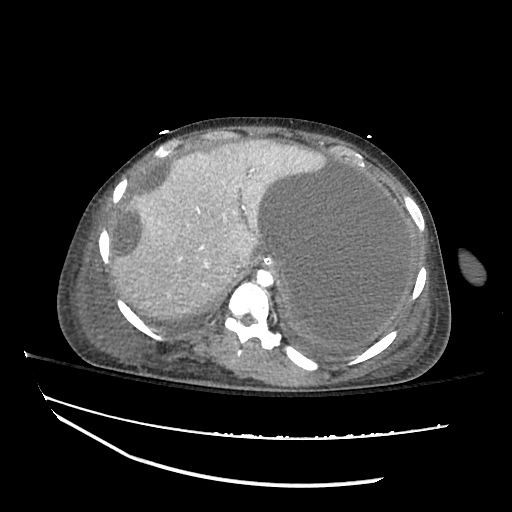

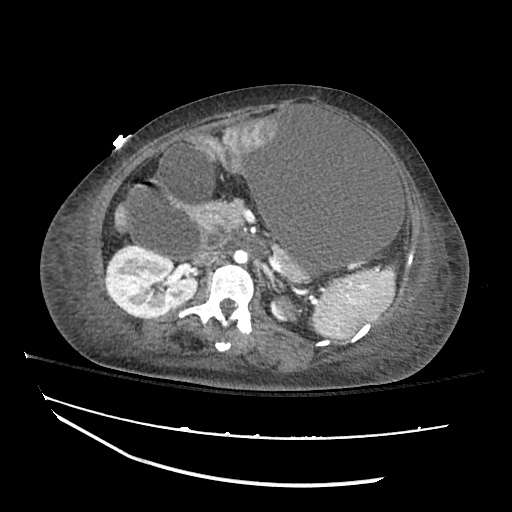

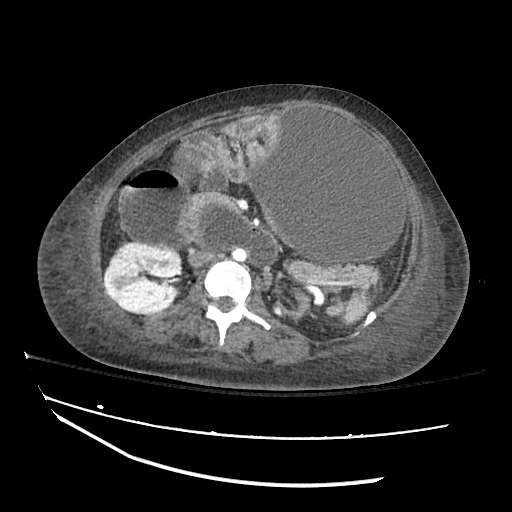

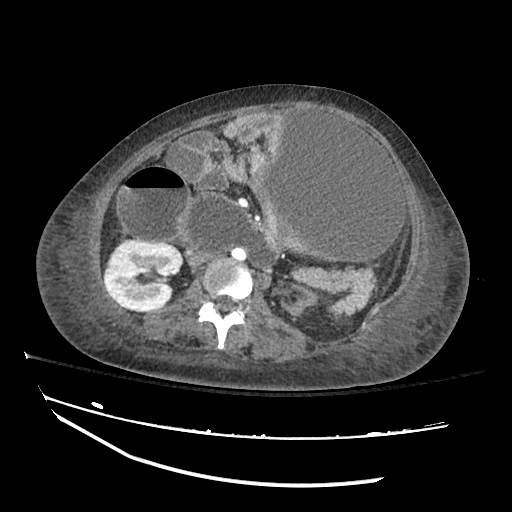

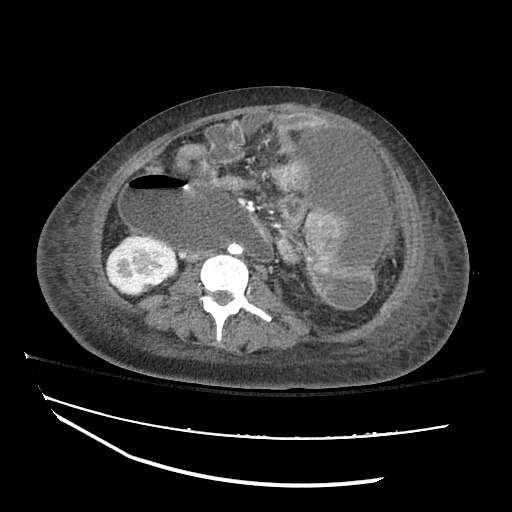

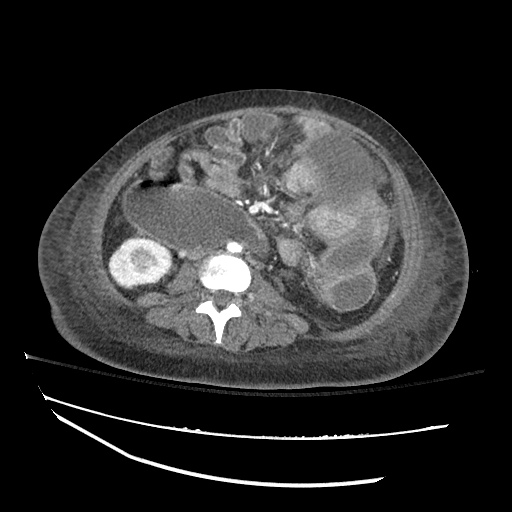

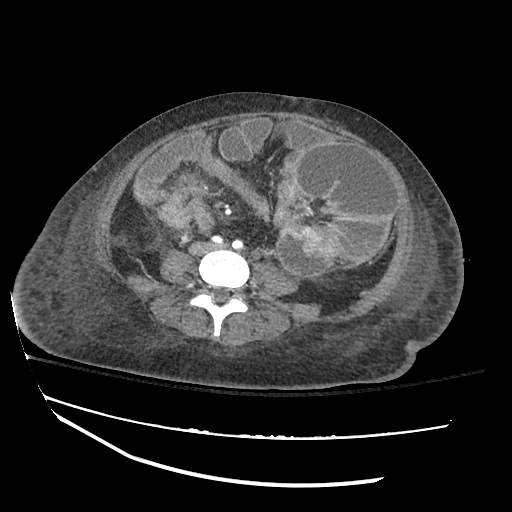

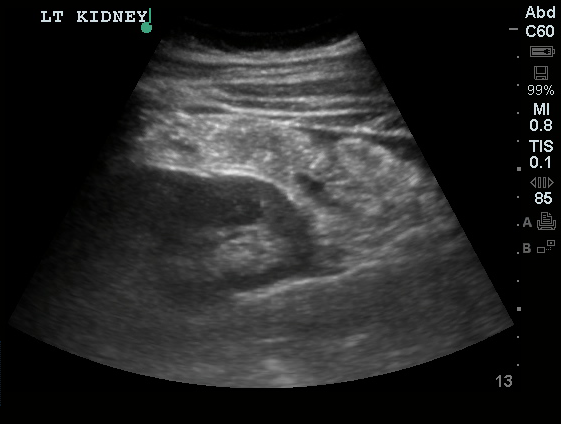

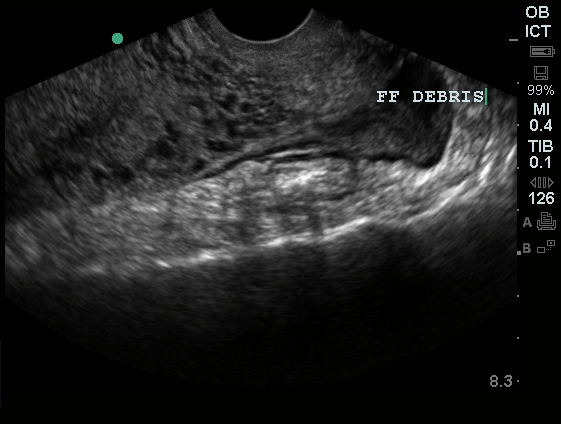

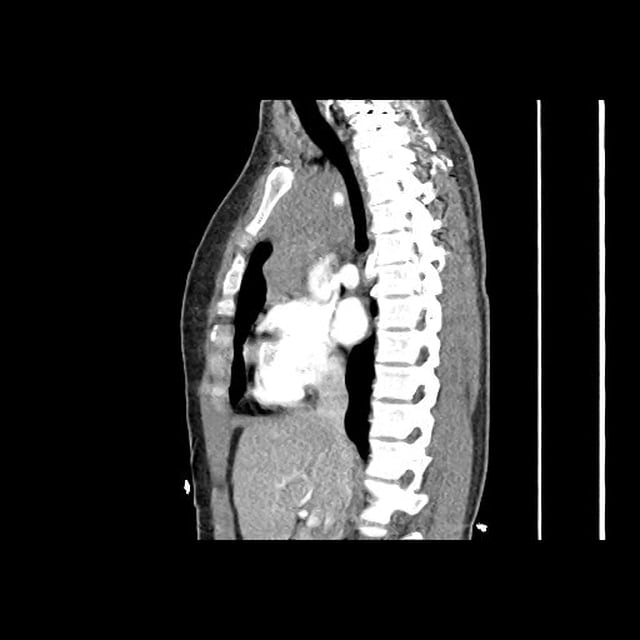

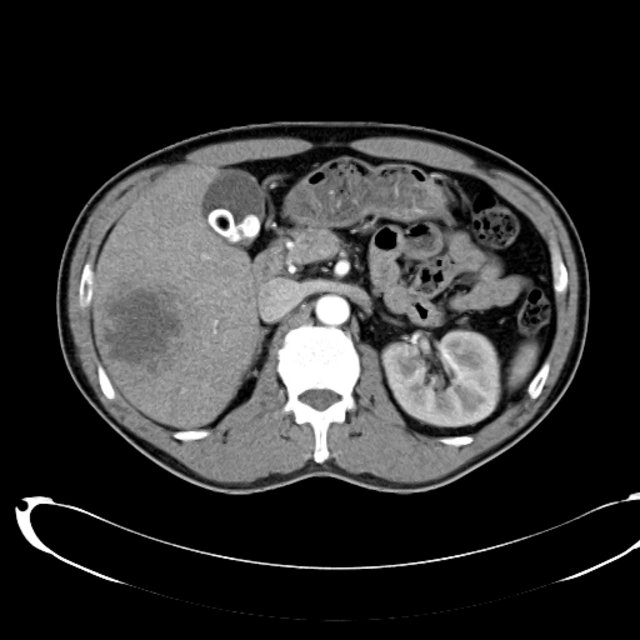

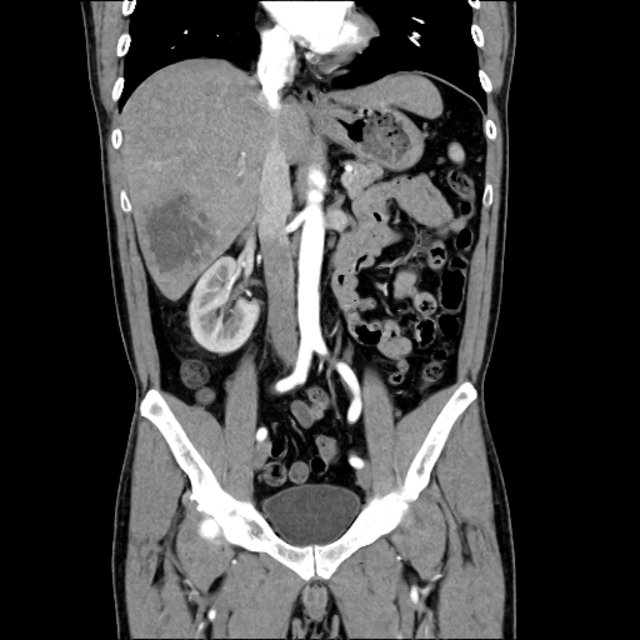

The patient was admitted ten days later, presenting with fevers, productive cough and pleuritic chest pain. Found to have a left lower lobe sub-segmental pulmonary embolus and antiphospholipid syndrome. She was also treated empirically for healthcare-associated pneumonia with cefepime and vancomycin given fever and productive cough though there were no imaging findings suggestive of consolidation and sputum cultures were negative.

Differential Diagnosis of Hypocalcemia: 1,2

Laboratory Evaluation of Hypocalcemia: 1,2

Clinical Manifestations of Hypocalcemia: 1

- Neuromuscular

- Hyperexcitability

- Perioral paresthesias

- Muscle weakness, cramps, fasciulations, tetany

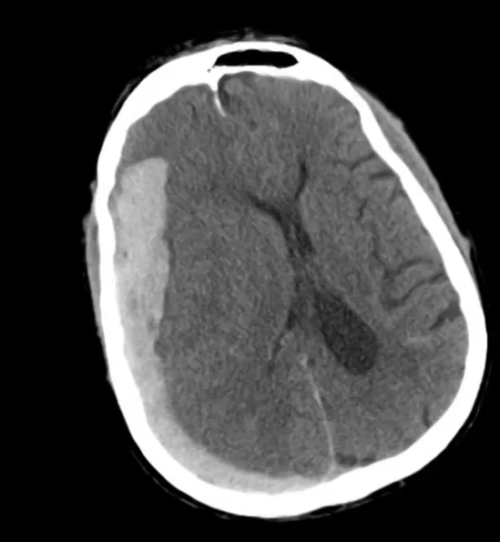

- CNS

- Depression

- Irritability

- Confusion

- Seizure

- Cardiac

- Decreased contractility/conduction

- QT prolongation

Management of Symptomatic Hypocalcemia: 1

- 10mL 10% Calcium Gluconate

- Dilute in 100mL D5W

Fever in SLE:

It is important to differentiate whether fever in a patient with SLE is due to disease activity (flare) or active infection.

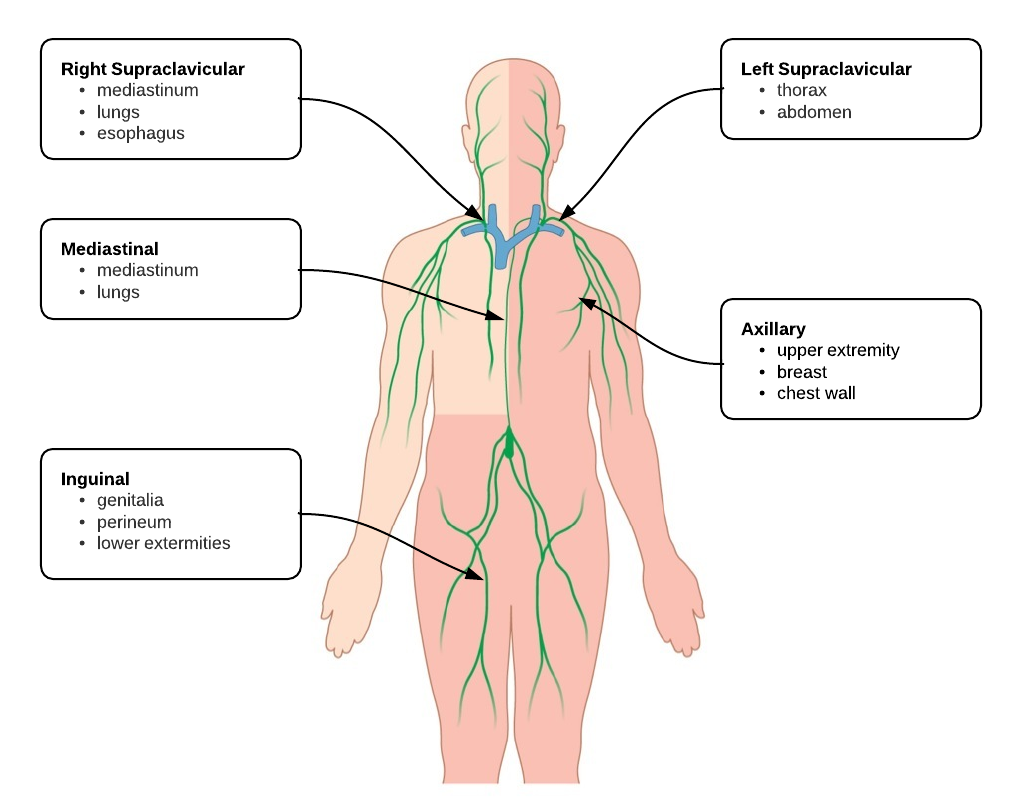

Risk Factors for Infection:3

- Neutropenia/Lymphopenia

- Hypocomplementemia

- Immunosuppressive therapy (especially Azathioprine4)

Laboratory Studies:3

- CRP: sensitivity 100%, specificity 90% >1.35mg/dL 5

- PCT: sensitivity 75%, specificity 75% 6

References:

- Cooper, M. S., & Gittoes, N. J. L. (2008). Diagnosis and management of hypocalcaemia. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 336(7656), 1298–1302. doi:10.1136/bmj.39582.589433.BE

- Hannan, F. M., & Thakker, R. V. (2013). Investigating hypocalcaemia. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 346(may09 1), f2213–f2213. doi:10.1136/bmj.f2213

- Cuchacovich, R., & Gedalia, A. (2009). Pathophysiology and clinical spectrum of infections in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatic diseases clinics of North America, 35(1), 75–93. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2009.03.003

- Zhou, W. J., & Yang, C.-D. (2009). The causes and clinical significance of fever in systemic lupus erythematosus: a retrospective study of 487 hospitalised patients. Lupus, 18(9), 807–812. doi:10.1177/0961203309103870

- Kim, H.-A., Jeon, J.-Y., An, J.-M., Koh, B.-R., & Suh, C.-H. (2012). C-reactive protein is a more sensitive and specific marker for diagnosing bacterial infections in systemic lupus erythematosus compared to S100A8/A9 and procalcitonin. The Journal of rheumatology, 39(4), 728–734. doi:10.3899/jrheum.111044

- Scirè, C. A., Cavagna, L., Perotti, C., Bruschi, E., Caporali, R., & Montecucco, C. (2006). Diagnostic value of procalcitonin measurement in febrile patients with systemic autoimmune diseases. Clinical and experimental rheumatology, 24(2), 123–128.